On February 3, the High Court of Australia ruled that the country’s offshore processing arrangements with Nauru are authorised under Australian law - but the court did not consider whether the policy comports with international law.

The immediate result is 267 asylum seekers - including 91 children, of whom 37 were born in Australia - are now at risk of involuntary transfer to indefinite limbo on Nauru, a fiscally bankrupt island in the middle of the Pacific.

Twenty-three men are also at risk of return to Manus Island, Papua New Guinea, some of whom suffer from serious physical and mental health problems.

Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull responded to the court decision by immediately proclaiming that “our borders are secure. The line has to be drawn somewhere and it is drawn at our border.”

The problem is the line is drawn on the wrong side of the relevant principles - that every asylum seeker who comes to Australia should have access to a fair and timely asylum process in Australia, and that Australia has an obligation to provide special protection for children.

The line is being drawn across the future of 37 infants, who were born in Australia, who have never been outside Australia, and who Australia should recognise as Australian citizens.

It’s being done at the expense of 54 children, 36 of whom currently sit in Australian classrooms.

And it will be done at the expense of more than a dozen women who will now be forcibly returned to Nauru after having suffered sexual assaults and harassment there.

Australia’s policy of transferring asylum seekers, including children, to offshore processing sites makes a mockery of Australia’s ratification of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which requires that: “[i]n all actions concerning children, whether undertaken by public or private social welfare institutions, courts of law, administrative authorities or legislative bodies, the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration.”

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) is unequivocal, stating that the “UNHCR has witnessed firsthand the severe impact on the mental and physical health of the asylum seekers and refugees as a result of long-term detention, conditions at the center, past delays in processing and the absence of timely solutions for anything other than a small number of refugees.”

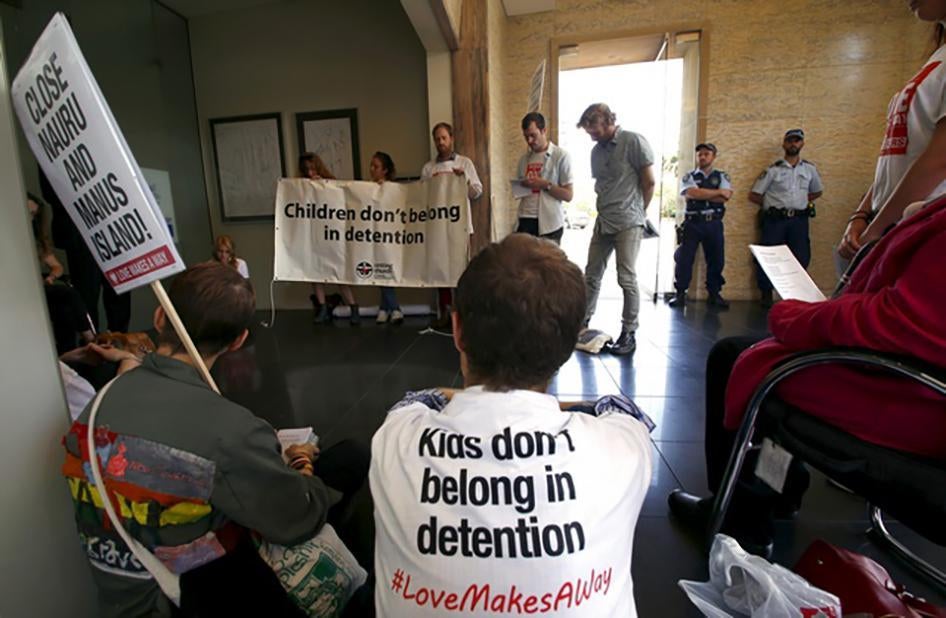

In response to the High Court decision, public protests have been held in major cities across Australia, church groups have offered sanctuary, and State Premiers in Victoria, Queensland, New South Wales and South Australia have extended offers to resettle the asylum seekers.

It’s not just the Australian people who are noticing what their government in Canberra is doing - other countries in the region are all too happy to see a green light from Australia in their own policies to turn back asylum seekers and refugees, hold them in indefinite detention, or send them back into harm’s way.

The most obvious example was the Thai, Malaysian and Indonesian political leaders and navy officers who pointed to Australia to justify playing a cruel game of “human ping-pong” by pushing off boats of Rohingya during the Southeast Asia boat people crisis of May 2015.

Cambodia has also repeatedly basked in Australian praise while pushing ethnic Montagnards fleeing political and religious persecution back into harm’s way in Vietnam. Australia’s efforts in Cambodia have seen millions of dollars spent to send just five refugees from Nauru to Phnom Penh, a colossal waste of taxpayer money.

Both Sri Lanka and Vietnam benefit from Australian silence on rights abuses in those countries because their governments work to stop boats of their desperate citizens leaving their shores.

Canberra’s muted reaction to Thailand’s outrageous act to force 109 ethnic Uighurs back to China in July, over the objections of UNHCR and much of the world community, spoke volumes for the tremendous damage that the Australia ‘stop the boats’ policy has done to the principle of human rights in foreign policy.

Now as Bangkok pursues Chinese dissidents, Australia is again silent.

Australia should recognise that it bears responsibility for safeguarding the human rights of these 267 asylum seekers, and refrain from transferring them to Nauru and Manus Island.

Instead, the leaders in Canberra should publicly announce that the government will provide fair and timely refugee status determination for them in Australia, and abide by the results - and for those found to be refugees, let them stay.