Are democratic revolutions in Arab Muslim countries good or bad for advancing the human rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people? There is only one case study to consider these days – Tunisia – and the verdict is still out.

Most Tunisians do not favor abolishing article 230, which criminalizes sodomy and lesbianism, says Baabou. Rather than trying to change public opinion, Baabou favors mobilizing civil society. So in January, Damj helped launch the Collective for Individual Liberties, an umbrella group of 30 Tunisian and international rights associations, including mainstream human rights and women’s rights groups. Abolishing article 230 figures prominently in the collective’s platform.

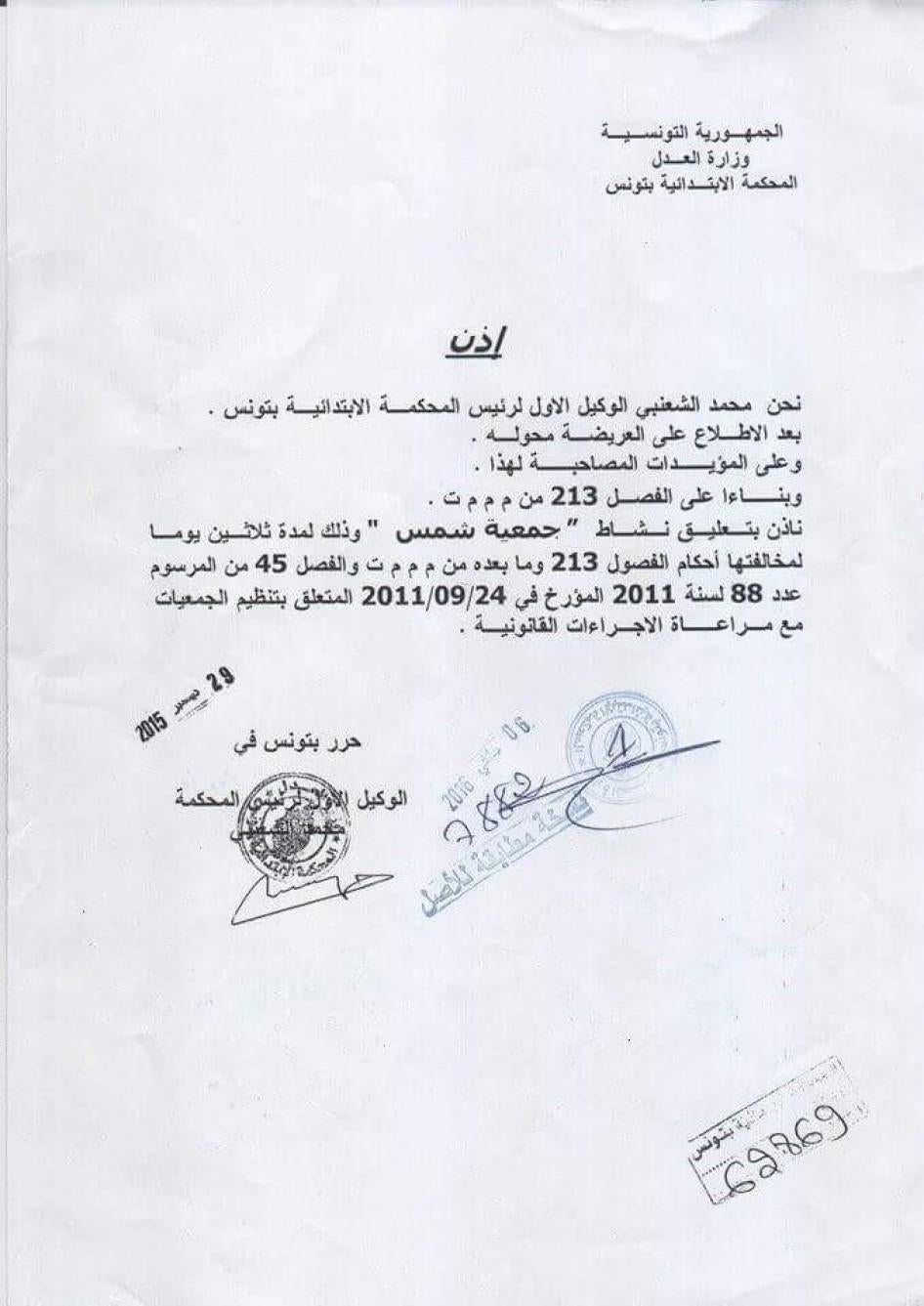

They will face stiff opposition. On January 4, a Tunis court, responding to a government complaint, suspended the LGBT association Shams for 30 days, on the grounds that gay rights declarations its president made on TV digressed from the objectives listed in Shams’s bylaws, which are to defend “sexual and gender minorities.”

When Shams was founded last May, Abdellatif Mekki, a prominent parliamentarian and ex-minister of health, urged its dissolution. “The Tunisian people had a revolution for freedom and so that every individual could enjoy his rights…not to found an associations to defend gays…. Homosexuals…should be punished as the law provides, because this kind of individual behavior is dangerous for society,” he said.

Whatever the ultimate fate of Shams, civil society in Tunisia has stoked a debate on sodomy laws that is more public than in neighboring countries. The debate over article 230 comes as civil society groups are challenging other seemingly popular laws such as Law 52, which provides a mandatory year in prison for marijuana consumption, and the Family Code provision by which women inherit only half as much as men do.