(Tunis) – The Tunisian authorities’ decision to suspend the activities of the LGBT rights group Shams is a setback for individual freedoms and equal rights in Tunisia. Shams works on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender rights.

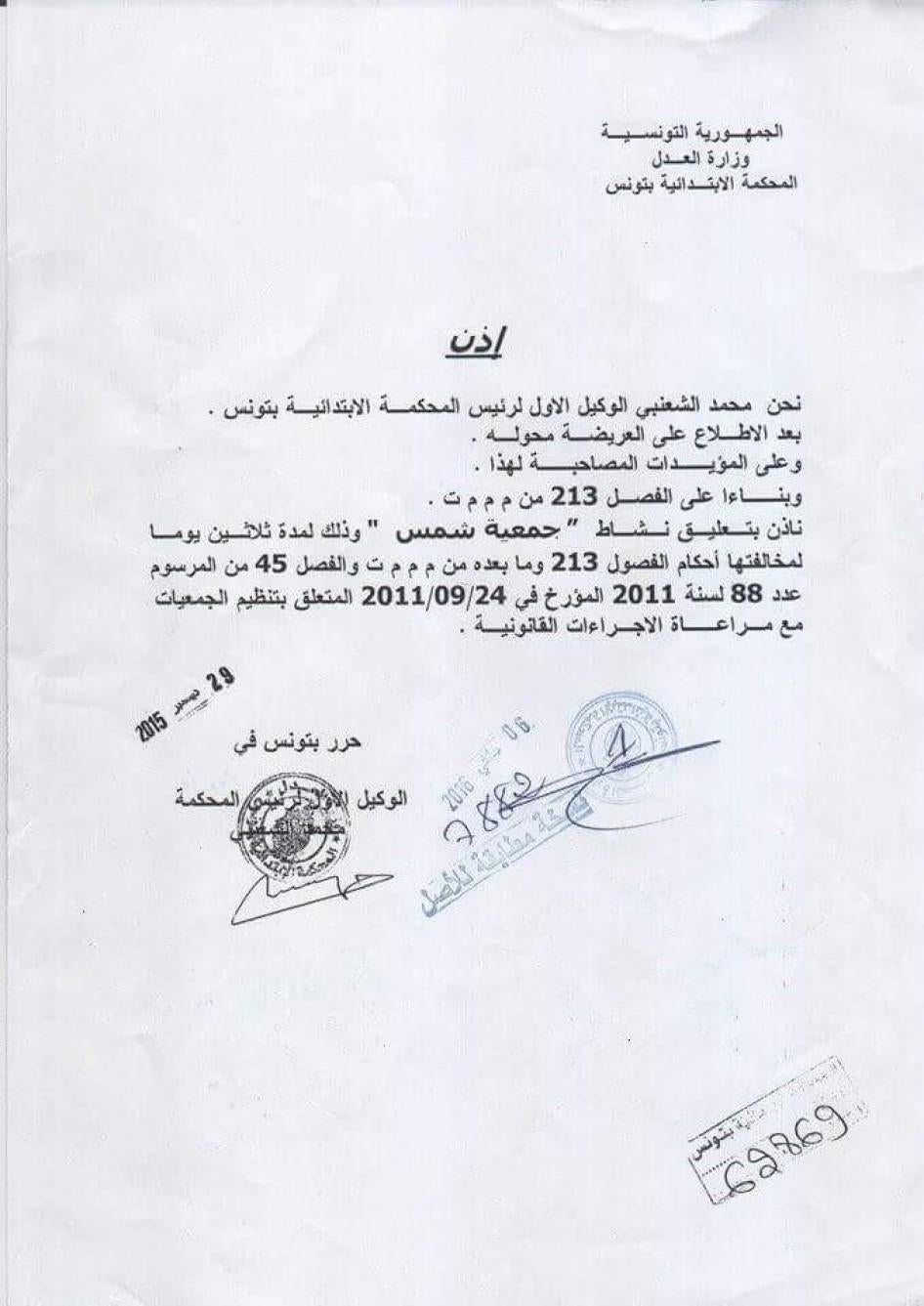

Shams registered with the government’s secretary general in May 2015, as an organization working to support sexual and gender minorities. On January 4, 2016, the first instance tribunal in Tunis notified the group that the court was suspending its activities for 30 days. The suspension followed a complaint by the government’s secretary general, who sent the group a warning to cease alleged violations of the association law in December. After the 30 days, the judiciary could order the association’s dissolution.

“Shams seeks to carry out basic human rights work, such as standing up for LGBT people who have been victims of violence,” said Amna Guellali, Tunisia director at Human Rights Watch. “This suspension denies them the chance to carry out this important work.”

The government’s complaint, filed by Kamel Hedhili, the head of state litigation, on December 15, 2015, alleged that the association deviated from its stated aim. The complaint, which Human Rights Watch has reviewed, quoted a media statement by the association’s members to the effect that Shams’s aim is to “defend homosexuals.” The complaint claimed that the wording violates article 16 of the decree law 88/2011 on associations, which requires associations to notify the authorities of any changes to its statutes. Hedhili also claimed that Shams has not completed its legal registration and thus lacks the legal status to pursue its work.

Neither point would appear to justify the suspension and potential shutdown of the organization under international law on freedom of association – under which such drastic acts should be restricted only to the most extreme cases. Furthermore, Shams presented evidence to the court suggesting that neither claim was factual. The law on associations, adopted by the transitional government in September 2011, requires associations to “respect the principles of the rule of law, democracy, plurality, transparency, equality and human rights,” as these are set out in international conventions that Tunisia has ratified, and prohibits incitement to violence, hatred, intolerance, and discrimination based on religion, gender, or region.

Shams’s statute, which Human Rights Watch has reviewed, is based on these principles, stating that its aim is “to support sexual minorities materially, morally and psychologically, and to press peacefully for the reform of laws that discriminate against homosexuals.” The government does not claim that Shams has engaged in violence or promoted intolerance or hatred, which could form a legitimate ground for its dissolution.

Furthermore, Shams has evidence that it completed the required steps for its legal registration. A receipt from the Official Journal of the Tunisian Republic, which Human Rights Watch has reviewed, shows that the association paid its announcement fees to the journal on May 19, 2015. Article 11 of the law on associations requires the journal to automatically publish the group’s statute “within fifteen (15) days of the date of deposit.” But the Official Journal has not published the association’s statute, the association’s secretary general, Ahmed Ben Amor, told Human Rights Watch.

The law on associations says that the judiciary has the authority to determine if an association should be suspended or dissolved. This involves a three-stage process, with an initial warning, followed by a government application to the Court of First Instance in Tunis for a 30-day suspension. If the association fails to correct any alleged infractions during that period, the court can order its dissolution.

Shams has drawn criticism from government officials due to its outspoken support for repealing article 230 of the penal code, which criminalizes sodomy and punishes it with three years in prison. Shams has publicly condemned recent arrests and prosecutions of men accused of homosexuality, including the conviction of a 22-year-old known as Marwen in the city of Sousse in September and the conviction of six male students on sodomy charges in December. Shams also denounced the use of forensic anal exams to “test” the men for evidence of homosexual conduct. The practice has no medical or scientific basis and can amount to torture.

In November, Ahmed Zarrouk, the government’s secretary general, called for Shams to be disbanded on the ground that it actively promotes the rights of homosexuals.

Shams has challenged its suspension at the administrative tribunal, a court in charge of settling disputes between the citizens and the administration, and is awaiting the decision.

Article 35 of Tunisia’s 2014 constitution guarantees “the freedom to establish political parties, unions, and associations.” Under article 22 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which Tunisia is a state party, any restrictions to the right to freedom of association must be “necessary in a democratic society” and “in the interest of national security or public safety, public order, the protection of public health or morals or the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.” Article 2 of the covenant requires countries to adhere to all the rights in the covenant, including freedom of association, without discrimination on any grounds.

In his 2012 thematic report to the Human Rights Council, the United Nations special rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association stated that: “The suspension and the involuntarily dissolution of an association, are the severest types of restrictions on freedom of association. As a result, it should only be possible when there is a clear and imminent danger resulting in a flagrant violation of national law, in compliance with international human rights law. It should be strictly proportional to the legitimate aim pursued and used only when softer measures would be insufficient.”

“The government’s harassment of Shams is in clear violation of international human rights standards,” Guellali said. “Suspending and closing an organization on such grounds would potentially put all rights organizations at risk.”