Summary

[The police] took me to the “morality ward” and kept me until 4 a.m. in a tiny room with no food or water. They took my phone and belongings. When they came back with a police report, I was surprised to see the guy I met on Grindr is one of the officers. They beat me and cursed me until I signed papers that said I was “practicing debauchery” and publicly announcing it to fulfill my “unnatural sexual desires.”

—Yazid, 27-year-old gay man from Egypt, July 17, 2021

[The police] searched all our phones. They took my phone and started sending messages to each other from my phone, then they took screenshots of those conversations and screenshots from my photo gallery. They took photos and videos where I have makeup or a dress on, and they used them as evidence against me. They went through my WhatsApp chats and took contact details so they could entrap my friends as well.

—Amar, 25-year-old transgender woman from Jordan, September 24, 2021

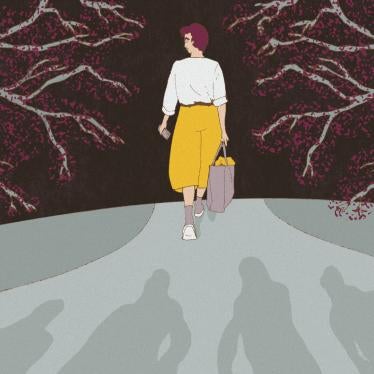

State actors and private individuals across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region have entrapped lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people on social media and dating applications, subjected them to online extortion, online harassment, and outing, and relied on illegitimately obtained digital photos, chats, and similar information in prosecutions, in violation of the right to privacy, due process, and other human rights. This report examines digital targeting in five countries: Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, and Tunisia.

Security forces have added these digital targeting tactics to traditional methods of targeting LGBT people, such as street-level harassment, arrests, and crackdowns, to enable the arbitrary arrest and consequent prosecution of LGBT people.

Based on 120 interviews, including 90 with LGBT people affected by digital targeting and 30 with expert representatives, including lawyers and digital rights professionals, this report documents the use of digital targeting by security forces and private individuals against LGBT people, and their far-reaching offline consequences. It also exposes how security forces employ digital targeting as a means of gathering or creating digital evidence to support prosecutions against LGBT people. Research for the report was supported by members of the Coalition for Digital and LGBT Rights: in Egypt, Masaar and an LGBT rights organization in Cairo whose name is withheld for security reasons; In Iraq, IraQueer and the Iraqi Network for Social Media (INSM); in Jordan, Rainbow Street and the Jordan Open Source Association (JOSA); in Lebanon, Helem and Social Media Exchange (SMEX); and in Tunisia, Damj Association.

The targeting of LGBT people online is enabled by their legal precarity offline. The criminalization of same-sex conduct or, where same-sex conduct is not criminalized, the application of vague “morality” and “debauchery” provisions against LGBT people emboldens digital targeting, quells LGBT expression online and offline, and serves as the basis for prosecutions of LGBT people. In the absence of legislation or sufficient digital platform regulations protecting LGBT people from discrimination online and offline, both security forces and private individuals have been able to target them online with impunity.

This report does not investigate the possible use of sophisticated spyware technology and surveillance by governments, but rather how authorities across the five countries manually monitor social media, create fake profiles to impersonate LGBT people and entrap them on dating applications such as Grindr and social media platforms such as Facebook, and unlawfully search LGBT people’s personal devices to collect private information to enable their prosecution. If the security forces are suspicious of an individual’s homosexuality or gender variance, they search their devices. Across the five countries covered, security forces searched LGBT people’s phones by forcing them to unlock their devices under duress by beating them or threatening them with violence.

In most cases covered in the report, security forces and prosecutors used photos, WhatsApp chats, and same-sex dating applications, such as Grindr, on LGBT people’s phones as a basis for their prosecution and abuses against them. They targeted and persecuted people based on their presumed or actual sexual orientation or gender identity.

Each chapter in this report presents a different form of online abuse and describes how that abuse negatively affects a person’s offline life; the harms do not end with the violation of privacy but reverberate throughout a victim’s life, in some cases for years after the online abuse.

Human Rights Watch documented 45 cases of arbitrary arrest involving 40 LGBT people in Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Tunisia. In every instance of arrest, security forces searched individuals’ phones, mostly by force or under threat of violence, to collect—or even create—personal digital information to enable their prosecution. Some LGBT people who had been detained told Human Rights Watch that when police officers could not find such digital information at the time of arrest, they downloaded same-sex dating applications on their phones, uploaded photos, and fabricated chats to justify their detention.

Human Rights Watch reviewed judicial files for 23 cases of LGBT people prosecuted based on digital evidence under laws criminalizing same-sex conduct, “inciting debauchery,” “debauchery,” “prostitution,” and cybercrime laws in Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Tunisia. Most of those prosecuted were acquitted upon appeal. In five cases, individuals were convicted, and their punishments ranged from one to three years of imprisonment. Twenty-two of the arrested LGBT people were not charged but were held in pretrial detention, in one case for fifty-two days at a police station.

In Egypt, in particular, Human Rights Watch documented 29 arrests and prosecutions, including against foreigners, suggesting a coordinated policy—either directed or acquiesced to by senior government officials—to persecute LGBT people.

LGBT people who were detained reported facing numerous due process violations, including having their phones confiscated, being denied access to a lawyer, and being forced to sign coerced confession statements. While detention conditions in the five countries are poor for everybody, LGBT detainees were subjected to mistreatment that was selectively and discriminatorily worse than that faced by other people in detention, including the denial of food and water, family and legal representation, and medical services as well as verbal, physical, and sexual assault. Some were placed in solitary confinement. Transgender women detainees were routinely held in men’s cells, where they faced sexual assault and other forms of ill-treatment. In one case, a transgender woman was detained at a police station, where she reported facing continuous sexual assault, for 13 months due to security forces’ confusion around her gender identity.

Laws against Same-Sex Conduct

Human Rights Watch documented 20 cases of online entrapment on Grindr and Facebook by security forces in Egypt, Iraq, and Jordan. Sixteen of those entrapped were arrested by security forces and subsequently detained. In these cases, security forces apparently targeted LGBT people online for the purposes of arresting them. The immediate offline consequences of entrapment range from arbitrary arrest to torture and other ill-treatment, including sexual assault, in detention.

In most prosecution cases as a result of entrapment, individuals were acquitted. Authorities held sixteen LGBT people in pretrial detention pending investigation, ranging from four days to three months, then sentenced them to prison terms ranging from one month to two years. Appellate courts overturned the convictions and dismissed charges in fourteen cases and upheld the convictions of two people but reduced their sentences.

Extortion is another form of digital targeting that LGBT people are particularly vulnerable to because of the mostly hidden nature of LGBT identities and relationships across the region, due to social stigma and the criminalization of same-sex conduct. Across the five countries, individuals trick LGBT people on social media and dating applications and threaten to report them to the authorities or out them online if they do not pay a certain sum of money (at times more than once).

Human Rights Watch documented 17 cases of extortion by private individuals on same-sex dating applications (Grindr) and social media (Instagram, Facebook) in Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, and Lebanon. Extortionists often pretended to be LGBT people in order to gain their victim’s trust, along with details about their personal lives—particularly digital information relating to their sexual orientation or gender identity—that can be used as blackmail. Organized gangs in Egypt and armed groups in Iraq are among the perpetrators of extortion.

In six cases, victims of extortion reported the perpetrators to the authorities, but all six were themselves subsequently arrested. In one case, the victim of online extortion in Jordan was prosecuted and sentenced to six months in prison based on a cybercrime law criminalizing “promoting prostitution online,” reduced to one month and a fine upon appeal. To the six interviewees’ knowledge, none of the perpetrators of extortion were prosecuted by the authorities.

Human Rights Watch documented 26 cases of online harassment, including doxxing—publishing personally identifiable information about an individual without their consent—and outing—exposing LGBT people’s identities without their consent—on public social media platforms in Jordan, Lebanon, and Tunisia. We also documented 32 cases of online death threats by armed groups on social media platforms in Iraq.

In 9 of the 26 online harassment cases, the victims appear to have been targeted due to their offline LGBT activism. In 17 of the cases, abuse by security forces or private individuals were followed by offline abuse, including arbitrary arrests and interrogations.

As a result of online harassment, LGBT people reported losing their jobs, suffering family violence, including physical abuse, threats to their lives, and conversion practices, being forced to change their residence and phone numbers, deleting their social media accounts, fleeing the country for risk of persecution, and suffering severe mental health consequences.

In most cases, LGBT individuals harassed with public social media posts reported the abusive content to the relevant digital platform. However, in all cases of reporting, platforms did not remove the content, claiming it did not violate company guidelines or standards.

Digital targeting has had a significant chilling effect on LGBT expression. All 90 LGBT people interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that after they were targeted, they began practicing self-censorship online, including whether they use certain digital platforms and how they use digital platforms and social media. Those who cannot or do not wish to hide their identities, or whose identities are revealed without their consent, reported suffering immediate consequences ranging from online harassment to arbitrary arrest and prosecution.

This report demonstrates that the digital targeting of LGBT people has far-reaching consequences. In Egypt, government digital targeting tactics have led to the arbitrary arrests and torture of LGBT people in detention by security forces. In Iraq, targeted LGBT people lived in constant fear of being set up by armed groups and reported being forced to change their residence (or, in some cases, even flee the country), delete all social media accounts, and change their phone numbers. In Jordan, LGBT people feel unable to safely express their sexual orientation or gender identity online, and LGBT rights activism has suffered as a result.

In Lebanon, LGBT people reported offline consequences of being outed online, including family violence, and arbitrary arrests by police based on unlawful phone searches and personal information found on devices. In Tunisia, the government has used digital targeting to crack down on LGBT organizing and to arrest and persecute individuals.

The accounts documented in this report demonstrate the severity of digital targeting of LGBT people in each country. The cases that are state-led apparently reflect government tactics to persecute LGBT people.

These five governments in the region are also failing to hold private actors to account for their digital targeting of LGBT people. Most LGBT people interviewed for this report said that they would not report a crime to the authorities, either because of previous attempts in which the complaint was dismissed or no action was taken or because they felt they would be blamed for the crime due to their non-conforming sexual orientation, gender identity, or expression. As mentioned above, six people who reported being extorted to the authorities ended up getting arrested themselves.

The lack of justice and impunity for abuses, coupled with the immediate harms from the digital targeting and impunity for those harms, have had long-term mental health impacts on LGBT victims of digital targeting. LGBT people recounted the isolation they experienced months and even years after the instance of targeting, as well as their constant fear, post-traumatic stress, depression, and anxiety. Many LGBT people reported suicidal ideation as a result of their experiences with digital targeting, and some even reported attempting suicide. Most of the LGBT people targeted online said they stopped using digital platforms and deleted their social media accounts as a result of digital targeting, which only exacerbated their feeling of isolation.

These abusive tactics highlight the prevalence of digital targeting and the need for digital platforms and governments to take action to ensure LGBT people’s safety online.

Key Recommendations

Digital platforms, such as Meta (Facebook, Instagram), Grindr, and Twitter, all of which have a responsibility to prevent online spaces from becoming tools of state repression, are not doing enough to protect users vulnerable to digital targeting. Digital platforms should invest in content moderation, particularly in Arabic, including by proactively and quickly removing abusive content that violates platform guidelines or standards on hate speech and incitement to violence, as well as content that could put users at risk.

Digital platforms should center the online experiences of those most vulnerable to abuse, including LGBT people in the MENA region, in driving policy and product design, including by engaging meaningfully with organizations defending LGBT rights in the region on the development and improvement of policies and features. This would involve soliciting and incorporating their perspectives and experiences at all phases of development, from design to implementation and enforcement, including on content moderation and trust and safety strategies that prioritize the concerns of LGBT people in the MENA region. Platforms should also provide context-specific information in Arabic to LGBT users and advise on their rights and the applicable law.

Finally, digital security development across all platforms should consider the realities of those most affected by digital targeting, including LGBT people in the MENA region. Those experiences should inform the design process in order to ensure a more secure digital experience for those at high risk, including for LGBT people who are vulnerable to the weaponization of digital platform use and other digital information.

Governments should respect and protect the rights of LGBT people instead of criminalizing their expression and targeting them online. The five governments should introduce and implement legislation protecting against discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation and gender identity, including online.

Security forces, in particular, should stop harassing and arresting LGBT people on the basis of their sexual orientation, gender identity, or expression and instead ensure protection from violence. They should also cease the improper and abusive gathering or fabrication of private digital information to support the prosecution of LGBT people. Finally, the government should ensure that all perpetrators of digital targeting—and not the LGBT victims themselves—are held responsible for their crimes.

Glossary

Bisexual: Sexual orientation of a person who is sexually and romantically attracted to both men and women.

Content Moderation: Refers to the process of ensuring user-generated content upholds platform-specific guidelines and rules to establish the suitability of the content for publishing. It involves the screening of inappropriate content that users post on a platform. The process entails the application of pre-set rules for monitoring content. If it does not satisfy the guidelines, the content gets flagged and removed. The reasons for removal include violence, offensiveness, extremism, nudity, hate speech, and copyright infringement.

Digital Evidence: Data that is created, manipulated, stored, or communicated by any device, computer, or computer system or is transmitted over a communication system, which is subsequently used in a legal proceeding.

Digital Targeting: Using digital media to select an individual or group as an object of an attack. In this report, digital targeting refers to the following tactics to target, and when done by state actors, to prosecute, LGBT people: entrapment on social media and dating applications, online extortion, online harassment and outing, and reliance on digital information in prosecutions.

Doxxing: Publishing personally identifiable information about an individual without their consent, sometimes with intent to provide access to them offline, exposing them to harassment, abuse, and possibly danger.

Entrapment: The action of tricking someone into committing a crime (under country-specific laws) to secure their prosecution. In this report, entrapment includes law enforcement’s impersonation of LGBT people on social media and dating applications to meet and arrest unsuspecting LGBT users on those applications based on their sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression.

Extortion: The practice of obtaining something, especially money, through coercion, force, or threats.

Gay: Synonym in many parts of the world for homosexual. In this report, gay refers to the sexual orientation of a man whose primary sexual and romantic attraction is toward other men.

Gender: Social and cultural codes (as opposed to biological sex) used to distinguish between what a society considers “masculine,” “feminine,” or “other” conduct.

Gender Expression: External characteristics and behaviors that societies define as “masculine,” “feminine,” or “other,” including features such as dress, appearance, mannerisms, speech patterns, and social behaviors and interactions.

Gender Identity: Person’s internal, deeply felt sense of being female or male, both, or something other than female or male. It does not necessarily correspond to their biological sex assigned at birth.

Gender Non-Conforming: Behaving or appearing in ways that do not fully conform to social expectations based on one’s assigned sex at birth.

Heteronormativity: A system that works to normalize behaviors and societal expectations that are tied to the presumption of heterosexuality and an adherence to a strict gender binary.

Homophobia: Fear of, contempt of, or discrimination against homosexuals or homosexuality.

Homosexual: Sexual orientation of a person whose primary sexual and romantic attractions are toward people of the same sex.

LGBT: Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender. In this report, LGBT is an inclusive term for groups and identities sometimes associated together as “sexual and gender minorities.”

Lesbian: Sexual orientation of a woman whose primary sexual and romantic attraction is toward other women.

Outing: The act of disclosing a lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender person’s sexual orientation or gender identity without that person’s consent.

Queer: An inclusive umbrella term covering multiple identities, sometimes used interchangeably with “LGBTQ.” Also used to describe divergence from heterosexual and cisgender norms without specifying new identity categories.

Rape: Any physical invasion of a sexual nature without consent or in coercive circumstances, of a person’s body by conduct resulting in penetration, however slight, of (1) any part of the body of the victim or of the perpetrator with a sexual organ or (2) the anal or genital opening of the victim with any object or any other part of the body.

Sex Work: The commercial exchange of sexual services between consenting adults.

Sexual Orientation: A person’s sexual and emotional attraction to people of the same gender, a different gender, or any gender.

Sexual Violence: Any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, or other act directed against a person’s sexuality using coercion, by any person regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any setting.

Transgender (also “trans”): Denotes or relates to people whose assigned sex at birth does not match their gender identity (the gender that they are most comfortable with expressing or would express given a choice). A transgender person usually adopts, or would prefer to adopt, a gender expression in agreement with their gender identity, but they may or may not desire to permanently alter their bodily characteristics to conform to their preferred gender.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch conducted the research for this report between February 2021 and January 2022. The researcher interviewed 90 LGBT people who had been targeted online and 30 activists, lawyers, and expert representatives of LGBT rights and digital rights organizations.

Human Rights Watch also reviewed judicial files in 40 cases of LGBT people prosecuted under laws criminalizing same-sex conduct, “debauchery,” “public indecency,” or “prostitution” laws between 2017 and 2022.

The research was done in collaboration with the following members of the Coalition for Digital and LGBT Rights, our partners, who provided invaluable support: in Egypt, Masaar and an LGBT rights organization in Cairo whose name is withheld for security reasons; In Iraq, IraQueer and the Iraqi Network for Social Media (INSM); in Jordan, Rainbow Street and the Jordan Open Source Association (JOSA); in Lebanon, Helem and Social Media Exchange (SMEX); and in Tunisia, Damj Association. These organizations supported Human Rights Watch in connecting the researcher with most of the interviewees and reviewed the report.

All interviews were conducted remotely, via phone or video call. Interviews were conducted in Arabic and English, and the former were translated into English. All interviews were conducted in a private setting.

At the time of the research, 27 interviewees resided in Egypt, 18 in Iraq, 10 in Jordan, 17 in Lebanon, and 13 in Tunisia. An additional two lived in France, two in Sweden, and one in Cyprus.

The LGBT people who had been targeted online whom we interviewed comprised 45 gay men, 27 transgender women, 15 lesbian women, 2 gender non-binary people, and 1 bisexual person. The abuses they recounted occurred between 2017 and 2022.

Human Rights Watch also reviewed online evidence of targeting against LGBT people, including videos, images, and digital threats.

The five countries covered in this report—Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, and Tunisia—were chosen based on abuses documented in previous Human Rights Watch publications on the intersection of LGBT rights and digital rights violations, as well as access to affected individuals and groups working on these issues. The report is neither meant to provide a fully comprehensive account of these violations in those countries, nor to suggest that other countries in the region are doing better. The report also provides examples of digital targeting in Kuwait, Morocco, and Saudi Arabia.

The report also does not undertake a country-level comparative analysis but highlights the tactics of persecution in each country to expose congruent policing and targeting methods across the five countries. This demonstrates the alarming trends in government tactics to digitally target LGBT people and violate their basic rights. This report’s multiple aims are to provide an evidence-based analysis of how LGBT people are affected when they are targeted online, to inform researchers and stakeholders on what needs to change, and to support digital platforms’ advocacy initiatives and policy changes to address and remedy these abuses.

All interviewees gave their informed consent and were informed they could stop the interview at any time or decline to answer any questions. Interviewees were not compensated for the interviews.

The names of most LGBT interviewees and their locations when we spoke with them have been withheld for safety reasons. The pseudonyms used in the report bear no relation to their real name. Interviewees’ ages at the time of the interview are provided.

I. Background

In 2021, 75 percent of the total population in the Middle East used the internet, higher than the global average of 65 percent.[1] Across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, LGBT people and groups advocating for LGBT rights have relied on digital platforms for empowerment, access to information, movement building, and networking.[2] In contexts in which governments prohibit LGBT groups from operating,[3] activist organizing to expose anti-LGBT violence and discrimination has mainly happened online. While digital platforms have offered an efficient and accessible way to appeal to public opinion and expose rights violations,[4] enabling LGBT people to express themselves and amplify their voices, they have also become tools for state-sponsored repression.

Authorities in Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, and Tunisia have integrated technology into their policing of LGBT people. Security forces across these countries[5] have combined traditional methods of targeting of LGBT people—such as street-level harassment, arrests, and crackdowns—with digital targeting—such as entrapment on social media and dating applications, online extortion, online harassment and outing, and reliance on private digital information in prosecutions—as tactics to target and prosecute LGBT people.

The public nature of digital platforms has granted authorities across the region increased access to LGBT people’s private lives. Dating applications and social media have become sites of potential violence and enabled government infiltration of private spheres where LGBT people congregate and organize.

The authorities across the five countries monitor social media and search LGBT people’s personal devices to collect images, text messages and chats, and other information that is subsequently used to persecute them. Any suspicion of homosexuality or gender variance may prompt security forces to search devices. Of the cases documented in this report that involve interactions between LGBT people and security forces, the security officers searched LGBT people’s phones, at times by force, in every instance. In most cases, selfies, other photos, chats, and the mere presence of same-sex dating applications, such as Grindr, were used by security forces and prosecutors to justify prosecution and abuses against LGBT people, based on their presumed or actual sexual orientation or gender identity.

Digital platforms are a lifeline for LGBT people across the region, who resort to online communication to meet, connect, date, raise their voices, share their stories of injustice, and organize their activism. While digital advocacy has contributed to reversing injustices against LGBT individuals,[6] governments have also used digital methods to monitor and target LGBT people, and they have a critical advantage on their side: anti-LGBT laws.[7]

Most countries in the MENA region have laws that criminalize same-sex relations.[8] Even the countries that do not—such as Egypt, Iraq, and Jordan— target LGBT people by weaponizing vague “morality,” “debauchery,” and prostitution laws.[9] Security forces and private individuals have thus exploited LGBT people’s legal precarity, and the absence of legislation protecting them from discrimination online and offline, to target them online.

The targeting of LGBT people online reflects their lived realities offline. Across the five countries, the criminalization of same-sex conduct or the application of vague “morality” and “debauchery” provisions against LGBT people emboldens digital targeting, quells LGBT expression online and offline, and serves as the basis for the prosecution of LGBT people. In recent years, government digital targeting has gained traction as a method to repress free expression and silence opponents. Concurrently, the application of anti-LGBT laws has extended to online spaces—regardless of whether online interaction leads to same-sex conduct—chilling even the digital discussion of LGBT issues.[10]

LGBT people who are most visible, including activists and transgender people, or vulnerable, due to intersecting forms of marginalization—based on class, legal status, pressure to conform to social norms, health status, and the lack of state protections, for instance—are more likely to be targeted. In Lebanon, for example, Human Rights Watch’s research findings suggest that LGBT refugees, especially from Syria, who face at least two forms of vulnerability during interactions with security forces—their LGBT identities and their refugee status—are more vulnerable to digital targeting.

All 90 LGBT people interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they practice self-censorship online, including how they use digital platforms and social media. Those who cannot hide their identities, who do not wish to do so, or whose identities are revealed without their consent reported suffering consequences ranging from online harassment to arbitrary arrest and prosecution.

The cases documented in this report illustrate the far-reaching offline consequences of government digital targeting of LGBT people in the five countries.

In Egypt, government digital targeting has led to arbitrary arrests and prosecution of LGBT people and their custodial torture and ill-treatment.

In Lebanon, government digital targeting has resulted in arbitrary arrests, reliance on improperly obtained personal digital information in prosecutions, and blackmail of LGBT people. In Tunisia, in addition to consequences similar to those in Lebanon, digital targeting has resulted in government crackdowns on LGBT organizing. In Iraq, digital targeting by armed groups forced targeted LGBT people to change their residence, delete all social media accounts, change their phone numbers, and sometimes flee the country for fear of being hunted down, blackmailed, and entrapped by armed groups. In Jordan, security forces have used digital targeting to entrap LGBT people, censor content related to gender and sexuality online, and intimidate LGBT rights activists.

The detailed accounts documented in this report demonstrate that these are not isolated incidents in each country. When state-led, they often reflect government tactics to digitalize attacks against LGBT people and justify their persecution.[11]

This report was conceived and executed during the Covid-19 pandemic. While digital targeting and online harassment in the MENA region predate the pandemic, their consequences spiked for LGBT people just as lockdown measures made it impossible to meet in person, curtailed access to groups that had offered safe refuge, diminished existing communal safety nets, threatened already dire access to employment[12] and health care,[13] and forced individuals to endure often abusive environments. Increased online bullying came with a rise in the outing of LGBT people, resulting in their expulsion from their homes, jobs, and schools.[14] When communication shifted entirely online, governments in the region used digital targeting to police free speech and as a basis for arbitrarily arresting LGBT people.[15]

The cases documented in this report demonstrate that digital platforms, such as Meta (Facebook, Instagram), Grindr, and Twitter, all of which have a responsibility to prevent online spaces from becoming tools of state repression, are failing to protect users vulnerable to digital targeting. Digital platforms should invest in content moderation, particularly in Arabic, including by proactively and quickly removing abusive content that violates platform guidelines or standards on hate speech and incitement to violence, as well as content that could put users at risk.

Digital security development across platforms should center the realities of those most affected by digital targeting, including LGBT people in the MENA region. Understanding the context of how LGBT people are targeted online, and how digital information is weaponized against them, should inform platforms’ design processes for a more secure digital experience. To do this, corporations that produce these technologies need to meaningfully engage with organizations defending LGBT and digital rights in the region, as well as with LGBT people, in the development of policies and features, including by employing them as engineers and in their policy teams, from design to implementation.

This responsibility does not only fall on social media companies. Unless governments across the region stop targeting LGBT people online, there will remain limitations to what digital platforms can do. However, the marked absence of government protection, the impunity afforded to perpetrators of digital targeting, and the dire lack of access to redress, highlight the pervasive offline consequences of online targeting, and the need for platforms to mitigate these risks by better securing LGBT people’s digital experience.

Digital Targeting Tactics: MENA Region Overview

Common digital target methods used in the MENA region are entrapment on social media and dating applications, online extortion, online harassment, outing and other doxxing, and reliance on improperly obtained private digital information in prosecutions.[16]

Entrapment

Online entrapment[17] in the MENA region dates to the early 2000s.[18]

Most of the LGBT people entrapped online are arrested and charged under laws criminalizing same-sex conduct (article 534 in Lebanon and article 230 in Tunisia), “debauchery” and “inciting debauchery” (articles 9 and 14 of the Law 10/1961 on the Combating of Prostitution in Egypt), and “soliciting prostitution online” (under article 9 of the cybercrime law in Jordan). Entrapment cases in Iraq did not have a clear legal basis.

In Egypt, the security forces, including Morality Police and National Security Agency officers, are a leading culprit in the entrapment of LGBT people, particularly after September 2017, when a photo of Sarah Hegazy, an Egyptian lesbian feminist, raising a rainbow flag at a Mashrou’ Leila[19] concert in Cairo[20] was posted on Facebook. It was shared thousands of times, with hateful comments and supportive counter-messages, initiating a digital debate.

The Egyptian government had been monitoring online activity, and days later, it initiated a crackdown in which Hegazy was arrested, along with dozens of other concertgoers, on charges of “joining a banned group aimed at interfering with the constitution.”[21] As part of a massive campaign to arrest people perceived as gay or transgender, the Egyptian authorities created fake profiles on same-sex dating applications to entrap LGBT people, reviewed online video footage of the concert, and also rounded up hundreds of people on the street based on their appearance.[22]

Hegazy, who was held in pretrial detention for three months, spoke about her post-traumatic stress after being tortured by police, including with electric shocks and solitary confinement.[23] She told her lawyers that police incited other detainees to sexually assault and verbally abuse her.[24] On June 14, 2020, she took her own life while in exile in Toronto.[25]

Online Harassment

In Morocco, a campaign of outing emerged at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic in April 2020.[26] People created fake accounts on same-sex dating applications and endangered users by circulating their private information on social media, including photos of men who used those applications, captioning the photos with insults and threats against the men based on their perceived sexual orientation.[27] Because of this outing, many LGBT people were expelled from their homes during a country-wide lockdown and had nowhere to go.[28] Moroccan LGBT activists informed Human Rights Watch about the outing phenomenon that caused panic among LGBT people who need to protect their privacy due to social stigma toward homosexuality and the legal prohibition of same-sex relations.

A 23-year-old gay university student told Human Rights Watch that his brother kicked him out of the house after learning of his sexual orientation when he was outed online. “I have been sleeping on the street for three days and I have nowhere to go,” he said in April 2020. “Because of the Covid-19 pandemic, not even my close friends are able to host me.” He feared for his safety if he tried to return to his brother’s house.[29]

The outing campaign in Morocco is just one example of similar pandemic-era efforts in the MENA region, including in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Tunisia.

In June 2022, an anti-LGBT campaign known as Fetrah (Arabic for “instinct”) went viral on Facebook and Twitter.[30] The campaign opposed “the promotion of homosexuality and its symbols” and encouraged social media users to post a pink and blue flag, symbols of normative gender identity, to demonstrate support for the campaign.[31] While Meta, the parent company for Facebook and Instagram, suspended the campaign’s page shortly after its inception, it remained active on Twitter with over 75,000 followers until it was eventually suspended in December 2022.[32] LGBT activists in the region spoke to Human Rights Watch about the dangers of the campaign, which has resulted in online harassment against LGBT people.[33]

On November 30, 2022, Moqtada al-Sadr, an influential Shia cleric in Iraq, posted a statement on Twitter calling for “men and women to unite all over the [Arab] world to combat LGBT people.”[34] In the statement, he added that this should be done “not with violence, killing or threats, but with education and awareness, with logic and ethical methods.” Despite calling for non-violence, al-Sadr’s statement fueled online harassment against LGBT people, prompting an online hate speech campaign that gained traction across Iraq.[35] Twitter did not remove the post, even after it and the campaign it promoted received media attention.

Activist organizations in the region play a significant role in navigating these threats and responding to LGBT people’s needs, regularly calling on digital platforms to remove content that incites violence and protect users. However, in most of the region, these organizations and activists are hampered by intimidation and government interference.[36]

Mohamad Al-Bokari, a 31-year-old Yemeni blogger, fled on foot from Yemen to Saudi Arabia after Yemeni armed groups threatened to kill him due to his online activism and gender non-conformity.[37] In 2020, while living in Riyadh as an undocumented migrant, he posted a video on Twitter declaring his support for LGBT rights,[38] which prompted online homophobic outrage from the Saudi authorities and the public on Twitter, leading security forces to arrest him.[39]

He was charged with promoting homosexuality online and “imitating women.” In July 2020, he received a sentence of 10 months in prison, a fine of 10,000 riyals (US$2,700), and deportation to Yemen upon release.[40] Saudi security officers had held him in solitary confinement for weeks, subjected him to a forced anal exam, and repeatedly beat him to compel him to “confess that he is gay.”[41] Although he has since been safely resettled with outside help, he remains isolated from his community and cannot safely return home.[42]

In October 2021, Maha al-Mutairi, a 40-year-old Kuwaiti transgender woman, was sentenced to 2 years in prison and a fine of 1,000 dinars (US$3,315) for “misusing phone communication” by “imitating the opposite sex” online under articles 70 and 198 of the penal code.[43]

According to al-Mutairi’s lawyer, the court used al-Mutairi’s social media videos to convict her on the basis that she was wearing makeup, speaking about her transgender identity, allegedly making “sexual advances,” and criticizing the Kuwaiti government.[44] On appeal, al-Mutairi was released without charge.[45]

This was not her first time in court. On June 5, 2020, the authorities had summoned al-Mutairi for “imitating women”—the fourth time she had faced the charge that year—after she posted a video online saying that the police had raped and beaten her while she was detained in a male prison for seven months in 2019 for “imitating the opposite sex.”[46] The police abused her yet again during her three days in detention, including by spitting on her, verbally abusing her, and sexually assaulting her by touching her breasts.[47]

The authorities released al-Mutairi on bail on June 8, 2020, without charge.

Reliance on Digital “Evidence”

In June 2021, police in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) issued arrest warrants against eleven LGBT rights activists who are either current or former employees at Rasan Organization, a Sulaymaniyah-based human rights group. The arrest warrants followed a lawsuit against Rasan by Barzan Akram Mantiq, the head of the Department of Non-Governmental Organizations in the KRI, a state body responsible for registering, organizing, and monitoring all nongovernmental organizations in the KRI.[48]

Activists implicated in the lawsuit told Human Rights Watch that when their lawyer visited the police station to inquire about the charges, police officers at the station referred to the written lawsuit, which indicated charges based on digital information under article 401 of Iraq’s Penal Code, which punishes “public indecency” with up to 6 months’ imprisonment and/or a fine of up to 50 dinars (US$0.03).[49]

On June 28, 2021, two of the activists said they went to the Sarchnar police station in Sulaymaniyah for interrogation. Police officers at the station inquired about the organization’s activities, referring to their Facebook page, which contained pro-LGBT statements and images, the activists said. Activists said police officers asked: “If you are registered as a women’s rights organization, why do you have LGBT-related content on your website and Facebook page?” Before leaving the police station, police officers made them sign pledges that they would not publish similar content in the future, activists said.[50] Activists told Human Rights Watch that police forced them to take down LGBT-related content from their public online pages.

In August 2020, the Egyptian National Security Agency arrested four witnesses to a high-profile 2014 gang rape in Cairo’s Fairmont Hotel (known as the Fairmont case),[51] along with two of their acquaintances.[52] The authorities subjected two of the arrested men, whom they suspected to be gay, to drug testing and forced anal exams.[53] Police also forced the men to unlock their phones and, based solely on their private photos, detained them for allegedly engaging in same-sex conduct.[54]

In an October 2020 report, Human Rights Watch found an unmistakable targeting pattern of LGBT people in Egypt:[55] authorities relied on personal digital information to track down, arrest, and prosecute LGBT people. People who had been detained said police officers, unable to find such information when searching their phones at the time of arrest, downloaded same-sex dating applications on detainees’ phones and uploaded pornographic photos to justify keeping them in detention.[56] The cases documented by Human Rights Watch suggested a policy coordinated by the Egyptian government, both online and offline, to persecute LGBT people.[57]

Afsaneh Rigot, a senior researcher on technology and human rights at Article 19, has also documented the reliance on digital information in prosecutions against LGBT people in Egypt, Lebanon, and Tunisia.[58]

Rigot told Human Rights Watch:

Documentation and research are highlighting that, with increasing vigor, digital evidence is becoming the cornerstone of prosecutions against LGBT people [in the MENA region]. In a context where something as intimate, complex, and private as gender identity and sexual orientation are essentially criminalized, we are seeing digital evidence become the main ingredient in these discriminatory prosecutions. Digital evidence–especially [on] people’s mobile devices–is now the scene of the crime. Yet as we look closer at prosecutions and sentences, what is deemed too queer to be legal is not defined.[59]

II. “It Was an Ambush”: Entrapment

I was chatting with a man on Grindr while sitting in the café. We agreed to meet at the café, but instead of the man I was expecting, five police officers in civilian attire walked in at about 9 p.m.… They [police officers] had a rope in the [police] car and threatened to hang me with it if I did not open my phone. They found private photos of me with long hair and other photos with a man and turned it into a case of debauchery and indecency.

— Ayman, 23-year-old gay man from Egypt, December 8, 2021

Human Rights Watch documented 20 cases of online entrapment by security forces on Grindr and Facebook in Egypt, Iraq, and Jordan, all three of which do not explicitly criminalize same-sex relations. The offline consequences of entrapment included arbitrary arrests, sexual assault, and other forms of ill-treatment, including torture, while in detention.

Human Rights Watch reviewed judicial files for 16 cases of LGBT people interviewed, including of one 17-year-old transgender girl, prosecuted under laws criminalizing “debauchery,” “public indecency,” and “prostitution,” as well as cybercrime laws, and found that authorities had arbitrarily arrested 16 people by entrapping them on Grindr and Facebook. The remaining four people entrapped were threatened with arrest.

Following their entrapment, those arrested, detained, and prosecuted all reported having their phones confiscated and unlawfully searched by security forces. Police officers relied on private photos, chats, and other information from their phones to arrest and detain them. In some instances, when police officers did not find any digital evidence, interviewees said police fabricated it to build a legal case against them. Prosecutors then used this digital content as the basis for arrest and indictment. Of the 16 entrapment cases for which Human Rights Watch was able to review judicial files, nearly all resulted in acquittals. In these cases, authorities held sixteen LGBT people (including the 17-year-old transgender girl) in pretrial detention pending investigation for periods ranging from four days to three months, then sentenced them to prison terms ranging from one month to two years. Appellate courts subsequently reversed the convictions and dismissed charges against 14 of the LGBT people and reversed their convictions. Two people had their convictions upheld on appeal, but the appellate courts reduced their sentences.

In addition to entrapment, interviewees said they were forced to sign coerced confessions, denied access to a lawyer, placed in solitary confinement, denied food and water, denied family visits, not permitted medication, verbally harassed, sexually assaulted, and otherwise physically abused. Transgender women were detained in men’s cells.

Authorities in Egypt subjected a 17-year-old transgender girl to a forced anal exam. Forced anal tests are sexual assault and violate the prohibition of torture and other cruel, degrading, and inhuman treatment or punishment.[60] They violate medical ethics, are internationally discredited because lack scientific validity to “prove” same-sex conduct.[61] The Egyptian Medical Syndicate has taken no steps to prevent doctors from conducting these degrading and abusive exams.

The documented cases suggest a tactic of security forces hunting down LGBT people online and then arresting, detaining, and inflicting torture or other ill-treatment on them.

Arbitrary Arrests, Unlawful Phone Searches, Due Process Violations

Maamoun, a 24-year-old gay man from Egypt, described an instance in February 2021 when he suspected police officers had used Grindr to entrap him:

Around 2 p.m., I went to a coffee shop in Central Cairo. Someone called Al-Khalidi texted me on Grindr, he said he was from the Gulf. It was not until later that I realized it was an ambush. I should have known better as his accent was fake and forced. I also tried to speak with him in English and received no response. He refused to send other photos and refused to have a video call with me. He also insisted that I give him my number so we could chat on WhatsApp. He immediately asked me to agree on a price in exchange for sex. I said that I did not care as long as it was a good time. We talked over WhatsApp, and he sent me his location, which was around a five-minute walking distance. I felt something was strange as I walked to the location. I called him when I arrived, and he said that he would meet me downstairs. I said I preferred to go to him so we would not be in the street, but he refused. I called an Uber immediately so I could leave.[62]

According to an Egyptian lawyer, security forces in Egypt who entrap LGBT people frequently pressure them to agree to a sum of money in exchange for sex to build a case against them.[63]

As Maamoun was crossing the street, he said, a police officer grabbed his arm, then four men in civilian attire cornered and handcuffed him.

One of them grabbed my phone and asked me if I pray. I said that I did. They put me into a microbus, which had six additional police officers, and they searched my bag. They found my HIV medication, as I am living with HIV. They did not understand when I told them it was an HIV medication until an officer said it was AIDS. The officers started spraying their hands with sanitizer and did not touch me. I was thankful that it got them to step away otherwise I may have suffered more harm.[64]

Maamoun said the police officers then took him to the Abbasiya police station, where he waited on the floor in a dirty room with no ventilation until 1 a.m. During this time, he said police officers verbally abused him and insulted him based on his sexual orientation. He was denied a phone call to a lawyer or family member and was not provided with food or water. Furthermore, although an officer allowed him to take his HIV medication that night, the police withheld his treatment for the rest of his detention. Police officers also took his phone, wallet, and personal belongings. Eventually, they forced him to sign a police report using his fingerprint, without giving him the chance to read it.[65]

Human Rights Watch reviewed the police report in Maamoun’s case, which stated that he “regularly engaged in same-sex relations in exchange for money,” based on Grindr and WhatsApp chats found on his phone.

At 1:30 a.m., Maamoun was transferred to the Qasr El-Nil police station, where he was placed in solitary confinement due to his HIV status, he said. At 8 a.m., police took Maamoun to Abdeen Court, where he said he was held in insanitary conditions until his interrogation:

The prosecutor asked me if I had a lawyer. I said I did not, so they appointed me a lawyer to be present during the interrogation. [The lawyer] told me not to worry and asked me which applications I had on my phone. I said Grindr and Facebook. He asked for my Facebook password, and I gave it to him so that he could access my account and delete content that could be used against me. He asked me if I had money, and I gave him my employer’s number. He also asked for my parents’ number. I refused at first, but he assured me that he would not tell them about the incident. The lawyer then told me that he called my employer, who told him that he did not know me. I felt like my life was over, like everything I had built was destroyed. I could not believe that all this degradation and hate I was experiencing was only because I am gay.[66]

According to Maamoun, at the public prosecutor’s office, the prosecutor interrogated Maamoun regarding chats on his phone, particularly on Grindr and WhatsApp. He said he claimed his phone was hacked, but the prosecutor did not believe him. When he requested that his court-appointed lawyer retrieve a friend’s number from his phone, Maamoun said the lawyer gave him a wrong number. He later discovered that the lawyer had also contacted his parents and told them, “Your son is detained for debauchery and immoral activity.” Maamoun’s father still does not speak to him because of this incident.

He continued:

On Monday, I went to the Abdeen court again for investigation, and I was put in that same terrible room. When I returned to the Qasr El-Nil police station, they changed my prison cell and placed me with high-profile felons. I was terrified and asked to be returned to my old cell, but the prison guard demanded 500 Egyptian pounds (US$32) and a phone card as a bribe. I experienced continuous sexual assault. One of the detainees with me in the cell forced me to confess that I was gay, and he sexually assaulted me in exchange for protection. This went on for a week, and other detainees sexually harassed me as well, while I was sleeping, and then when I was showering. We were 45 people in a tiny cell, and they were using drugs the entire time.[67]

After Maamoun spent 10 days in pretrial detention without charge, the judge ordered his release, he said.

Ayman, a 23-year-old gay man from Egypt, said he was entrapped on Grindr and arrested by police while he was out with three of his friends at a café in Cairo, on November 17, 2020.

I was chatting with a man on Grindr while sitting in the café. We agreed to meet at the café, but instead of the man I was expecting, five police officers in civilian attire walked in at about 9 p.m. They handcuffed [all four of] us and took us to the Smouha Police Department (morality unit) in their police car and beat us there while calling us names like “faggot,” “whore,” “son of a bitch.”

They [police officers] had a rope in the [police] car and threatened to hang me with it if I did not open my phone. They found private photos of me with long hair and other photos with a man and turned it into a case of debauchery and indecency. They found chats on my phone by accessing my Grindr, WhatsApp, and Facebook Messenger. They accused us of running an online sex business for profit, turning it into a case for economic court. They threatened us, that they would add photos on our phones to incriminate us further, but I don’t know if they did that or not because we haven’t seen our phones since.[68]

Economic courts have jurisdiction over violations of the 2003 telecommunications law and the 2018 cybercrime law, which restrict online content deemed to undermine “public morals” or “family values” and criminalizes the use of the internet to “commit any other criminalized offense.”[69] Afsaneh Rigot, who has researched the trend in Egypt toward referring LGBT cases to economic courts,[70] told Human Rights Watch: “This shift signifies a dark new era in anti-LGBT prosecutions [in Egypt]. They [authorities] are using very broadly defined cybercrime laws to increase chances of convictions, bringing in more charges [against LGBT people] with higher sentences.”[71]

After five hours at the Smouha police station, police transferred Ayman and his friends to Bab Sharqi detention center, where they spent a month. “It was a terrible place,” Ayman added. “Everyone slept on the floor in a very crowded tiny room. We were only offered appalling food that was impossible to digest.” [72]

After two days, at the public prosecutor’s office, Ayman said he endured further mistreatment and insults.

We were told that we will never get out of jail. The prosecutor wrote things in the report that were false. He searched our phones again, especially WhatsApp, Facebook, and Instagram, and insisted that we were running an online sex business. I had a lawyer with me, and the prosecutor asked him, “Aren’t you ashamed to defend faggots?” Then the lawyer left.[73]

After four days of being detained in Bab Sharqi, Ayman and his friends were presented before a judge, who extended their pretrial detention for 15 days. After their new lawyer, whom their families appointed, appealed, the judge reduced their pretrial detention to seven days. When they returned to court a week later, a different judge sentenced them to two years in prison for “debauchery” and “indecency.”

Ayman said he tested positive for Covid-19 after 15 days in Bab Sharqi detention center. He was denied medical care and access to medication from his parents. The police did not try to contain the spread, and the inmates, who were kept in cells with no ventilation, all became very sick, Ayman added. [74]

On appeal, Ayman and his friends were found innocent, but their case was transferred to the economic court. He said the economic court charges included “soliciting debauchery” and “conducting sexual business deals online,” based on the police report reviewed by Human Rights Watch.

On December 27, 2021, Ayman and his friends were acquitted.[75]

Yazid, a 27-year-old gay man from Egypt, said he was meeting another man in downtown Giza, after chatting with him on Grindr, when police officers approached them, accused them of “selling alcohol,” and arrested them in September 2019. While being held in the “morality ward,” he discovered that the man he met on Grindr was a police officer, he said. The officers beat and verbally abused him until he confessed to “practicing debauchery” and to publicly announcing it to fulfill his “unnatural sexual desires,” he added.[76]

The next day, Yazid said police officers took him to the prosecutor’s office in Dokki, a district in Giza City. The prosecutor insulted him: “You’re the cheap faggot they caught, son of a disgusting whore, do you fuck or get fucked?” He then renewed Yazid’s detention for four days, Yazid said.

They took me [back] to the Dokki police station, beat me so hard I lost consciousness, then threw me in a cell with other prisoners. They told them, “He’s a faggot,” and told me, “Careful not to get pregnant.” I stayed one week in that cell, and between the beatings by officers and sexual assaults by other detainees, I thought I would not survive.[77]

After a week, police officers took him to Giza Central Prison, which is inside the Giza Central Security Forces Camp:

They announced my charges as soon as I walked in, took turns beating me, and yelled heinous profanities at me. They put me in solitary confinement. I asked why, the officer said: “Because you’re a faggot. If I leave you with them [security officers], they will fuck you or you’ll pass the contagion [of homosexuality] on to them, you motherfucker.” I had to bribe soldiers so they would stop torturing and humiliating me.[78]

On September 30, Yazid had his first court hearing at Giza’s Dokki Misdemeanor Court, which acquitted him. He said:

When I went back to get the paperwork from the station, I was surprised that the prosecution had appealed the decision. I eventually found a lawyer who appealed my case, and the verdict was again “innocent.”[79]

Amar, a 25-year-old transgender woman from Jordan, was entrapped by police officers in Amman on April 4, 2019. She told Human Rights Watch:

I received a phone call from my friend [who is gay]. He asked me to “pick him up from a friend’s place.” His voice did not sound right. He texted me the directions to the apartment, which was in downtown Amman. Out of good will, I went there, and my friend opened the door. His face was bruised from being beaten, and there was another man behind him. When I walked in, I saw that there were four men in civilian clothing other than my friend. They said, “How do you like this surprise?” One man said, “We are from the anti-narcotics department. Don’t be scared, we just want to make sure you don’t use any drugs.” They took my wallet, my bag, and my phone and put me in one of the rooms. I could hear my friend screaming from the other room from all the punches and slaps. They insulted me and cussed at me because of the way I looked, saying I bring shame to my family because I was, in their eyes, a gay man. My tongue was tied. I felt like my body was there, but my mind was somewhere else.[80]

Amar said her friend who called her later explained how he had been entrapped on Grindr by a police officer, who lured him into the same apartment after pretending to be a gay man and inviting him to the apartment for a “date.” Following his entrapment, Amar said her friend told her police officers searched his phone, which they forced him to unlock by using violence, and made him reveal the contacts of other LGBT people he knew, including Amar’s. Police officers then forced Amar’s friend to call her and invite her to the apartment to entrap her as well.

Amar said that while at the apartment, she witnessed the entrapment of another Jordanian transgender woman by the police officers. “One of the officers pretended to be an Emirati man and even put on traditional Emirati attire. I heard the police officers talk about how they were going to entrap her [trans woman] on Grindr,” Amar said. At around 9 p.m., the other trans woman arrived at the apartment, where she thought she was meeting an Emirati man for a date, only to join Amar and her friend, Amar said.

Amar said the police officers then forced Amar and the other trans woman to unlock their phones, under threat of violence, and began collecting and creating digital information to build a case against them.

They took my phone and started sending messages to each other from my phone, then they took screenshots of those conversations and screenshots from my photo gallery. They took photos and videos where I have makeup or a dress on, and they used them as evidence against me. They went through my WhatsApp chats and took contact details so they could entrap my friends as well. They made me wear a wig and took pictures of me.

At 1:30 a.m., the officers took us all [Amar, her friend, and the other trans woman] to a [police vehicle], in the parking lot, a Volkswagen Transporter [T5] van, and drove to the Amman Cyber Crimes Unit…. They [police officers] handcuffed us, took our phones and all our belongings, even our shoelaces. When we arrived at the Cyber Crimes Unit, I found out that we were arrested under the pretense of using social media platforms to solicit prostitution, based on the police report they forced me to sign. When the three of us got there, there wasn’t one officer in the entire unit who spared us: they all showered us with insults and slapped us around as we were walking. Everybody stared at us in the most demeaning ways. Sometimes people would open the door to look at us and laugh while we sat there with our heads to the ground, unable to say anything back.[81]

Amar described the room she was placed in at the Amman Cyber Crimes Unit as a “cage in a zoo,” and due to overcrowding, she fainted. When she came to, one of the police officers who was at the apartment told her to go to the bathroom and make sure no one was watching. In the bathroom, she said he forced her to undress, raped her, and then told her not to mention it to anyone. After that, the officers forced her to sign a police report without allowing her to read it. Amar’s police report, as reviewed by Human Rights Watch, indicated that she was accused of “practicing sodomy in exchange for money” and “soliciting prostitution” on social media.[82]

The next day, police officers took her, her friend, and the other trans woman to the North Amman Court in al-Jubeiha. “It took the judge seconds to send us to prison,” Amar said. “She did not even look at us. It was all based solely on the police report.”[83]

The police officers then took all three to a pretrial detention facility:

Before we entered, all our belongings were put in a box and kept in police custody. The cells were completely empty: there were no mattresses, nothing to sit on. The room was filled with people who were sleeping on top of each other. During our interrogation, police officers called in their friends [other police] to listen for entertainment, because, they said, “they were bored.” They called me by my deadname [the name that Amar was given at birth] and addressed me with male pronouns. We experienced every kind of degrading filth and hatred.[84]

Next, the police officers took all three to another prison in Amman, where the warden refused to receive them due to the case against them. “I will not welcome these faggots,” Amar remembered the warden shouting. Consequently, the police officers took them to Juweideh prison in Amman.

Amar described the underground cell in Juweideh prison where she was detained for four days:

When we entered the room, I saw a transgender woman and a gay man who were arrested on the same charges as me 21 days prior. I knew one of them personally. Everything you go to prison for was still happening in prison—the drugs, the sex, the thievery. There were mandatory protocols in the cell pertaining to sleeping and eating hours. They also had a black market in the cell. We weren’t allowed to leave our rooms at all. My friend and I slept on the same bed when we first got there, but my friend was released the same day because one of his parents was in the army and had connections. As for myself, no one knew I was in prison. To make a phone call, I had to buy a card that allowed me to enter the phone booth and call for no more than five minutes. Nothing was for free. I had to pay for food and calls.[85]

Amar was released on bail after four days. After eight court hearings, the charges against Amar were dropped:

My lawyer told me that they [anti-narcotics department officers] had fake accounts on social media applications, where they lured in people with the help of an informant who is paid by the police, a sum of 20 Jordanian dinars (US$28) per person. The informant is asked to lure people to a predetermined place, get paid for it, and then leave unscathed. These informants use fake numbers, passport papers, license plates to hide their identity. It would take them [informants] several months of very normal conversations with someone to hand them in.[86]

Amr, a 33-year-old gay man from Egypt, was entrapped by police on Facebook in April 2018.

I was contacted by this Facebook account pretending to be my friend whom I knew well and asking me to meet him. I went to meet him in the afternoon, and I started getting skeptical when he asked me what I was wearing. I tried to turn back, but then four police officers in civilian attire appeared and arrested me. They handcuffed me and said, “Come with us and keep your mouth shut.” They snatched my phone from my hand and took me to the Agouza police station.[87]

At the station in Giza Governate, the police officers forced Amr, under threat of violence, to open his phone. He was not worried because he did not have any incriminating dating applications or chats on his phone. When they did not find any such information on his phone, they downloaded Grindr and fabricated chats that they uploaded onto his phone, Amr said. Amr was not allowed to call a lawyer. He was charged with “inciting debauchery” and detained for two months. He spoke about the ill-treatment he endured during his detention:

They [police officers] verbally abused me by calling me “faggot” and cursing me and my family. They also took turns putting out their cigarettes on my arms. They pushed me around and slapped me. During my interrogation, where they did not give me a chance to speak, they forced me to give them contacts of my LGBT friends. I signed the police report without receiving the chance to read it. They told me that they will put me in prison so that I become a man and get cured from my “illness.”[88]

Amr spent two weeks at the Agouza police station, after which he was taken to Al-Saf prison for a week, and then moved him back to Agouza police station. At a court hearing at the Al-Giza Court after one week of his detention, he said:

The judge did not speak to me, he just read the report and sentenced me to one month in prison and one month probation, then he told them [the police officers] to get me out of his face. I also never got my phone back.[89]

In September 2017, when Hanan, a 22-year-old transgender woman from Egypt, was a 17-year-old girl, she said she was entrapped through Facebook and arbitrarily arrested by Egyptian security forces in a Cairo restaurant.

I had been talking to a man on Facebook, and he asked to see me. We met at a restaurant three days before the Mashrou’ Leila concert in Cairo. I had a ticket to the concert in my backpack. I arrived to find four men dressed in civilian clothing waiting for me. I knew I was being arrested.[90]

The police officers searched her phone after forcing her, under threat of violence, to unlock it, logged into Grindr through her Facebook account, and created a fake chat to upload pictures of her as a woman. They did not inform her of any charges against her. They also made her strip at the police station, examined her body, and asked her private questions, such as: “Do you shave,” “How did you get breasts?,” “Why do you have long hair?,” and “Why do you have a ticket to a Mashrou’ Leila concert?”[91]

After hours of verbal abuse, Hanan stopped responding. Then, the officers began beating her:

They slapped me, kicked me with their boots, dragged me by my clothes until they ripped apart. I was sobbing and couldn’t talk. The officers would slap me and stab me with their pens to force me to speak. They threatened to make me undergo a forced anal exam. I told them to go ahead, I had nothing to hide. They then ordered a forensic doctor to subject me to the anal exam.[92]

At the prosecutor’s office, Hanan was asked about the pictures on her phone. She denied that it was her, but she recalled the prosecutor saying to her: “Even the pictures of you dressed as a man incriminate you. You either confess now or you will never leave.” Despite the prosecutor’s curses and screams, she refused to confess, so the prosecutor then told her he would detain her for three days while she decided whether to confess.[93]

Hanan said:

I was detained in a cage under a stairway [at the prosecutor’s office], it wasn’t even a prison cell, [but merely] a 3-by-2-meters tiny room, with 25 gay and transgender people. They refused to let me call anyone or hire a lawyer. I couldn’t sleep. I was delirious, in shock, I felt like I had to be alert or they would kill me. I cut my own hair with scissors so I could look “normal” when I was interrogated again.[94]

After three days, Hanan was transferred to a cell with several men.

I was harassed, sexually assaulted, verbally abused, mocked. They touched me in my sleep. I stopped sleeping. The officers beat me and said, “We will teach you how to be a man.” They water-hosed me when I resisted their abuse.[95]

Hanan was held in pretrial detention for a total of 2 months and 15 days after the prosecutors kept postponing her trial.

Finally, a court sentenced her to another month in prison for “inciting debauchery.” Despite being released for time served, the charge stayed on Hanan’s record for three years.

When I was being released, the officer asked me, “Are you a top or a bottom?” I did not understand what he meant, so he kept me in detention for another night even though I was ordered released. The next day, he asked me again. I said “top.” He responded, “Good boy.”[96]

Asaad, a 29-year-old gay man from Egypt, said he was entrapped by police on Grindr in May 2017. He said:

I met a guy on Grindr. He asked me to meet him near Tahrir Square. It was 8:30 p.m. When I told him that I had arrived, two men came up to me and asked me for directions, then three men came from behind me and one of them called my name. Before I could even answer, they had taken my phone and handcuffed me. They told me that their cameras had spotted me throwing a bomb in the dumpster. They told me to go with them to the Qasr El-Nil police station for interrogation. I had never been to a police station before. When we went inside an officer told me, “I finally got you!” They searched my bag and took everything. They took my picture and fingerprints. They made me sign a police report without reading it.[97]

The next morning, the officers took him to the public prosecutor’s office in Abdeen, downtown Cairo. “When I tried to speak, [the prosecutor] said, ‘Shut up. You’re not allowed to speak here, you faggot,’’’ Asaad said. Afterwards, Asaad was taken back to the Qasr El-Nil police station. His pretrial detention was renewed for 45 days, which he spent at that police station.[98]

Asaad described the conditions of his detention to Human Rights Watch:

I could not sleep at all. I was detained in a tiny room with other men [for four days]. We could not even sit on the floor, and we had to stand on one foot to fit. I was transferred to a bigger cell when my detention was renewed for another 45 days. I was detained with a bunch of thugs. One of them stuck a needle in my thigh while I was sleeping. I did not dare tell anyone about it because he could have killed me. I could not walk for weeks. I was beaten by police officers and prison guards, who slapped me hard across the face every chance they got. They threatened that they would insert bottles into my anus as a form of torture. They verbally harassed me constantly.[99]

Human Rights Watch reviewed the police report and court files in Asaad’s case. The police report mentioned the dating application, WhosHere, not Grindr, and it also contained screenshots of chat messages between Asaad and other men as well as nude photos. Asaad told Human Rights Watch that he had never downloaded WhosHere on his phone or sent nude photos to anyone. After the judge in Abdeen court heard his story, he ordered Asaad’s release on June 6, 2017.[100]

In September 2017, the prosecutor appealed, and Asaad received a one-year sentence in absentia on January 6, 2018. Asaad said his lawyer advised him to go into hiding for three years to escape detention. He eventually fled Egypt on July 9, 2018. On March 6, 2021, Asaad was acquitted after bribing the police.[101]

Abuse of Power: Sexual Violence and the Threat of Arrest

Zoran, a 25-year-old gay man from Sulaymaniyah, in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, said he met a man on Grindr on October 26, 2021. On November 4, 2021, they decided to meet in a public place. He said:

We met at a café, then went to the bazaar and walked around. He told me, “I’m an actor, you will discover I’m really good at acting.” I thought it was strange but did not comment. He then took a picture of me on Snapchat and added a filter that made me look bald. He showed me the picture and said, “Soon, your head will be shaved like this.” I hated the picture and asked him to delete it.[102]

However, the date continued, and Zoran’s date expressed wanting to hug and kiss him.

He insisted we go to the bathroom and kiss there. I was afraid someone would see us, but I trusted him, so I obliged. The moment we entered the bathroom and he began kissing me, two Asayish [security forces] officers knocked on the bathroom door, then broke it and entered. They began beating me with a baton, on my legs, my chest, my back, my face, all over my body. They did not beat my date, who turned out to be one of them. They cursed me and called me a “faggot.” One of them said, “You look like a man, not a gay, why do you do this?”[103]

Zoran said the police officers threatened to arrest him, call his family, and imprison him for 15 years. When Zoran tried to explain himself, an officer took him to a police car, where the officer asked Zoran to download Grindr on his phone, which he did. Then the officer sexually assaulted him.

He told me, “You’re very handsome, you need to be with someone older than you. You should be mine.” He touched my chest, my hand, my body, and my penis. He touched his penis while he was touching mine. While doing this, he asked me, “What kind of penis do you like? Large? Small?” After he finished, he drove me to my car and let me go.[104]

“I should have known he [my date] was sending me signals that I would be arrested, but I only realized later that it was entrapment, and he worked for the police,” Zoran said.[105]

In March 2018, Nour, a 31-year-old non-binary person from Zagazig, Egypt, who uses they /them pronouns, met a man on Grindr who entrapped them. After the two chatted for a few weeks, they spoke on WhatsApp and the man asked to meet Nour. On April 4, 2018, Nour went to see him in Masr Al-Jadidah, a suburb outside Cairo. Nour described what happened when they arrived:

He convinced me to get into an Uber with him despite my initial hesitation. I started chatting with the Uber driver as well, who told me he was from a well-off family and that he studied at the German institute. I started talking about Angela Merkel and he said, “Isn’t she that American woman?” That was when I knew I was in trouble.…[106]

I began to get extremely anxious when the man I was with seemed to have lost the directions to his own house. The driver then stopped to ask for directions from a police officer, who was driving a government Jeep. As soon as we stopped, five men with hockey sticks stepped out of a car that sped toward us. One of those men pulled me out of the car by grabbing me by my scarf and choking me. Then he beat me up.[107]

Nour pushed the man away and ran as fast as they could, running and hiding in a villa’s yard and then at a construction site. They called for help via social media: