On December 13, the people of the Central African Republic (CAR) went to the polls to vote in a referendum on a new constitution. Like many others in the past three years of the war-torn country’s history, the day was marred by violence. At least five people were killed and 34 wounded during clashes in the capital, Bangui, according to Reuters. Authorities were forced to extend the vote for a second day. Voters overwhelmingly backed changes to the constitution, including the imposition of a two-term limit for future presidents, but the violence did not bode well for the overdue presidential and legislative elections set for December 27. It served as a clear reminder of the challenges that lie ahead for a new government.

CAR descended into chaos in late 2012, when a coalition of mostly Muslim rebels, known as The Séléka , ousted the government of president Francois Bozizé. Their brief rule was marred by widespread violence and human-rights abuses and in mid-2013 groups of Christian and animists, known as the anti-balaka, rose up against them. Thousands were killed and hundreds of thousands fled their homes as both sides targeted each other and civilians.

With the state imploding and no president in place, the international community scrambled to set up a semblance of governance. In January 2014, a transitional government was created, headed by Bangui’s former mayor, Catherine Samba-Panza. It had no functioning police, army or judicial officials and was forced to rely on international peacekeepers for security. Its key function was to pave the way for elections. Dates were set and repeatedly missed due to violence, lack of funding and messy preparations. If no single presidential candidate wins an outright majority on December 27, a runoff is scheduled for January 31.

Elections may still be interrupted. On December 14, Nourredine Adam , one of Seleka’s most notorious leaders, declared an autonomous region in the northeastern part of the country, though both the transitional government and the United Nations (U.N.) quickly denounced his move.

If elections do occur and a new government is put in place, here are some of the critical challenges it will face:

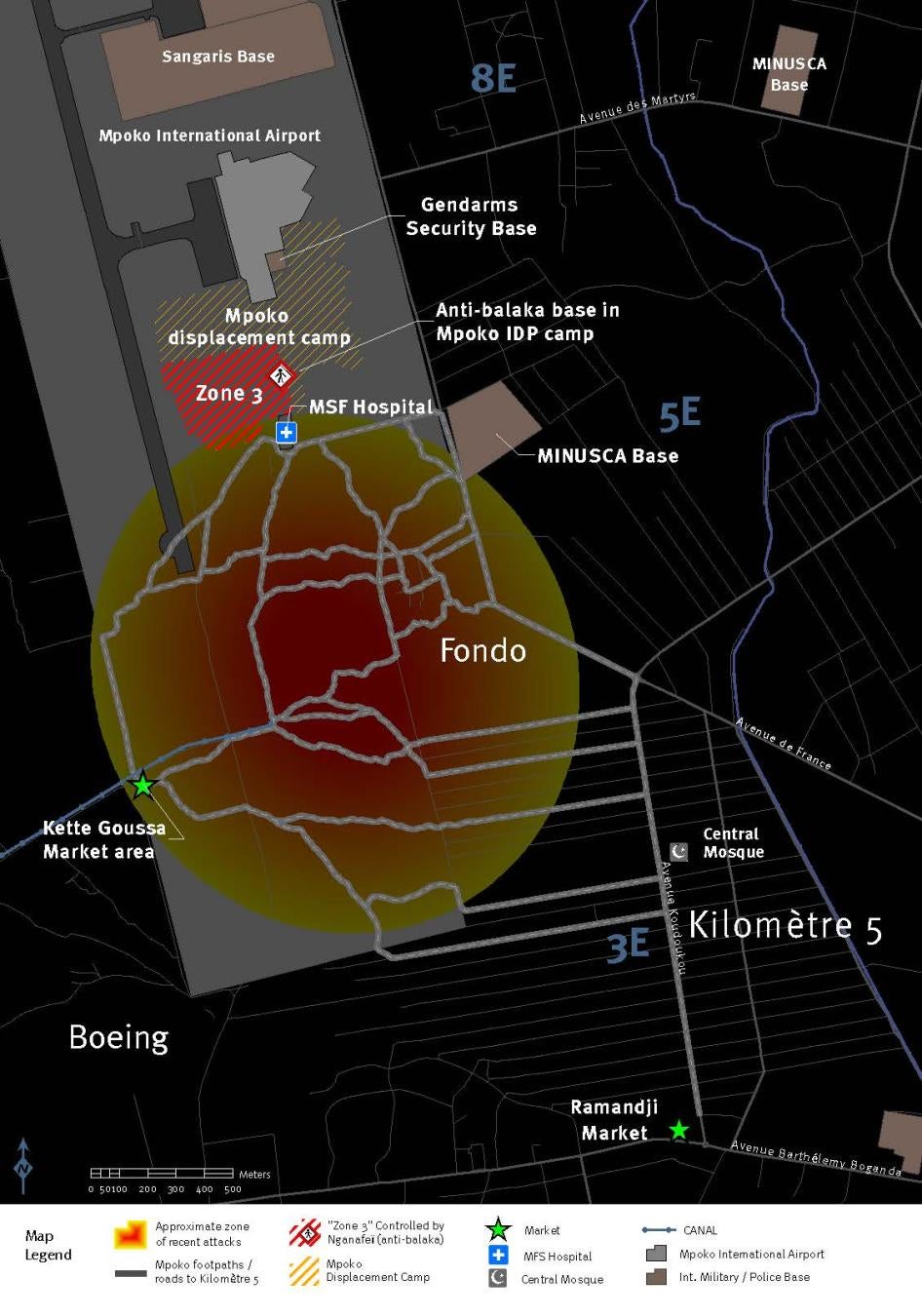

Addressing the violence: A new government will inherit a deeply divided country where sectarian violence remains rife. From September to November, over 100 people were killed in the capital in brutal tit-for-tat revenge killings. The new government will have to reduce tensions and protect civilians from further attacks.

Tackling impunity: Taking power by violent means, often accompanied by abuses, has been the fastest route to power in CAR. Yet none of those who have been responsible for widespread human rights violations have ever faced prosecution. The new government will inherit a barely functioning justice system, though a new Special Criminal Court could help. The court was created by the transitional government and will have national and international judges and prosecutors to focus on grave international crimes committed since 2003. It’s not yet operational, and to succeed it will require significant technical and financial support from international donors, but it could send an important warning to potential election spoilers that they could face justice if they engage in criminal activity. To ensure accountability for the most serious crimes, the new government will also need to cooperate closely with the International Criminal Court, whom the transition government requested to start a second investigation in September 2014.

Disarming rebel and militia groups: To restore government control, disarming and finding new occupations for combatants will be critical. The new government will need to rely heavily on U.N. peacekeepers and others for help on this, while at the same time restructuring the national army, the police and other security forces. The country remains under an arms embargo, imposed by the U.N. Security Council in December 2013. Any re-arming of the army would need to take into account the serious human-rights abuses some soldiers and their commanders may have committed during the violence in recent years.

The return of refugees and displaced people: An estimated 456,000 people, the majority Muslim, remain refugees outside of the country, while another 469,000 are displaced internally, including some 36,000 Muslims living in enclaves. Many of the displaced live in abysmal conditions. The new government will need to provide assistance to people still afraid to return home, while also improving security conditions so they can return safely.

Donor support: For any new government to succeed, it will need significant international financial and security support. Keeping potential donors engaged in a world where there are multiple crises will require deft diplomatic skills and evidence that progress is possible. The U.N. has agreed to maintain its sizable presence for the next year, but France has already reduced its peacekeeping force. Key donors like the European Union and the United States provide some financial assistance, but retaining and even increasing this support will be necessary for a new government that is likely to inherit a stalled economy.

What will really change the course of events in CAR is a government that acts to protect the rights of all the country’s citizens. Pope Francis said it best when he was in CAR in November: “the time for hating, revenge and violence is in the past.”

Lewis Mudge in an Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch. He tweets @LewisMudge .