Every time I travel in South Sudan, I think of my former colleague and friend Jemera Rone, who died in Washington, DC yesterday. Jemera worked for Human Rights Watch for more than 20 years and was a true human rights pioneer, as well as a generous mentor and colleague.

She opened and staffed Human Rights Watch's first field office in the early 1980s, starting the practice of placing our researchers in the midst of war zones that is now routine.

Jemera was among the first human rights investigators to document violations of international humanitarian law or “the laws of war,” laying the foundation for today’s research and reporting on conflict zones from the Democratic Republic of Congo to Syria.

(To read other reflections on Jemera visit our memorial page).

But back in El Salvador in the 1980s, when she started reporting on laws-of-war violations, hardly anyone in the human rights movement was doing it. It meant reporting not only on government abuses, but those of rebel groups as well. Many were hostile to the idea, arguing that rights groups should focus on only government rights violations. Judgments about war crimes, they said, were too difficult to make.

Jemera showed this research could be done carefully and accurately--her research survived the intense scrutiny of the Reagan administration, which was backing the abusive Salvadoran government--and her reporting on rebel abuses as well highlighted Human Rights Watch's impartiality.

Her detailed reporting also helped establish the organization's methodology, showing that carefully documented facts could cut through partisanship and ideology to put pressure on abusers – and those backing them – to stop.

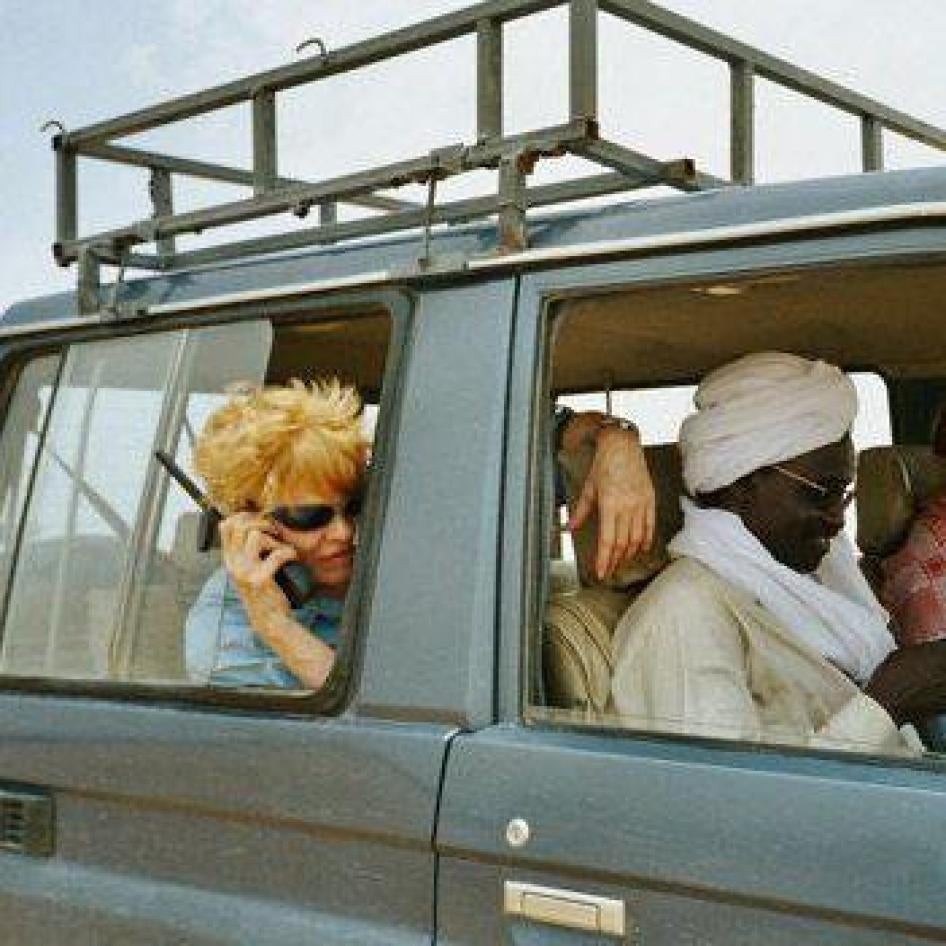

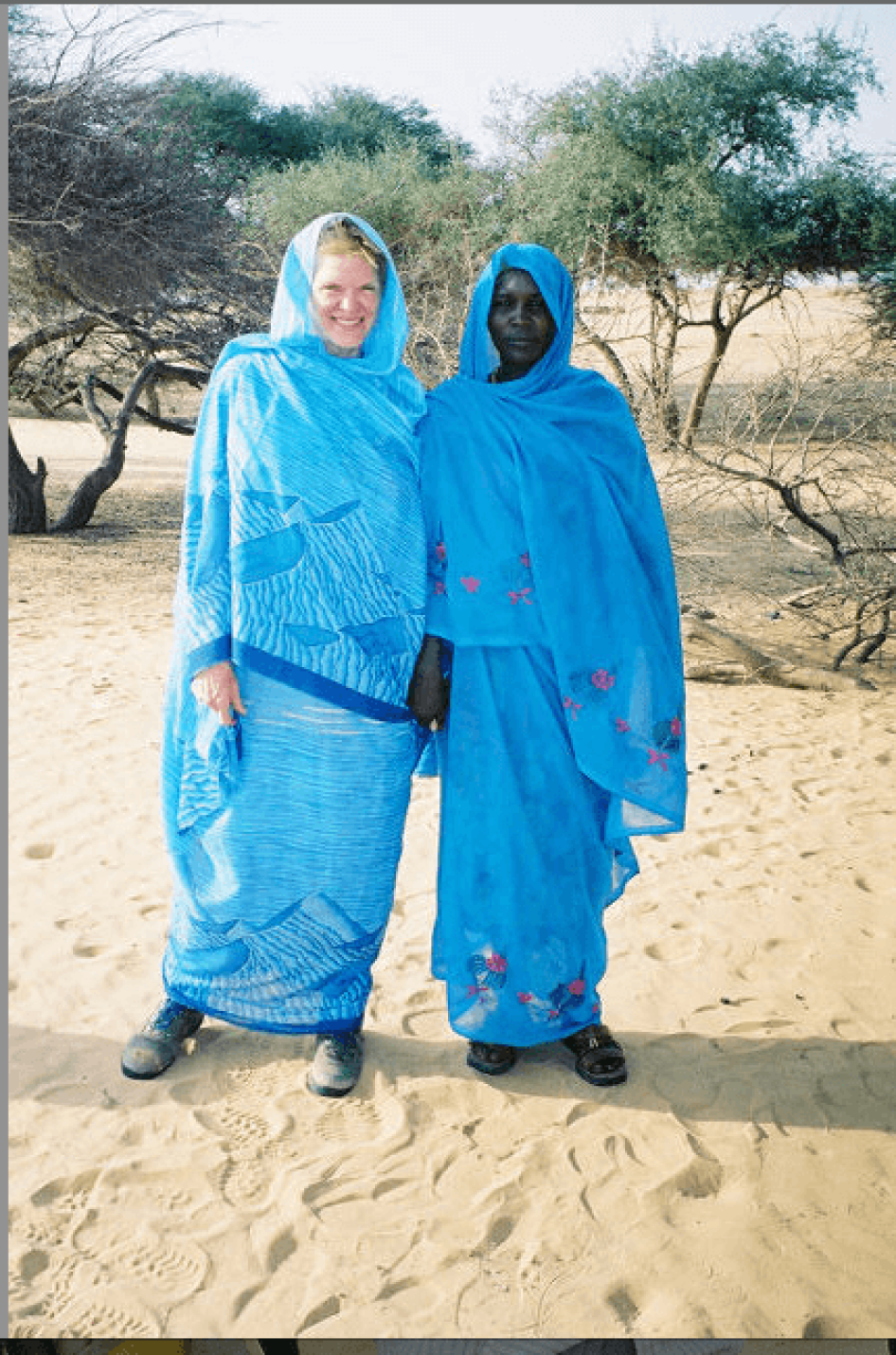

However, it is her 15 years of research on Sudan that may be her greatest legacy. Jemera is a household name to so many Sudanese and South Sudanese leaders, journalists, aid workers, and ordinary people -- anyone who followed Sudan’s long 1983-2005 north-south civil war, really.

She literally “wrote the book” on the horrendous human rights abuses by all sides in the conflict, investigating and documenting in extraordinary detail the atrocities committed by the government in Khartoum as well as the Sudan People’s Liberation Army and other rebel groups.

“Civilian Devastation,” her 1994 report for Human Rights Watch on Sudan’s conflict, is the most detailed description available of how civilians then – as today – were slaughtered because of their ethnicity and suffered massive destruction and pillage of their villages and towns.

Her research on the 1998 famine in Bahr-el-Ghazal, which uncompromisingly laid the blame for the needless deaths from hunger on systematic human rights abuses, was unprecedented and helped change the way we think about responsibility for famine.

Her 567-page tome on the impact of the oil industry in South Sudan’s Greater Upper Nile region, “Sudan, Oil and Human Rights,” remains the uncontested history of exploration and extraction of oil and the massive forced displacement of local populations and other horrific human rights abuses that took place. It’s also a devastating description of personal schisms between abusive leaders and the use of ethnicity to pit people against each other with terrifying results, foreshadowing the current violence in South Sudan.

“Members of [these] communities continue to be killed or maimed, their homes and crops burned, and their grains and cattle looted,” she wrote then. The same kinds of abuses have again been committed against civilians this year in Unity state, in the same places she researched with such rigor.

Jemera was passionate, committed and prescient. Back in 1994, in a telling warning of the devastation we see in South Sudan today, now led by the same men who were then its rebels, she wrote:

“The leaders of the SPLA factions must address their own human rights problems and correct their own abuses, or risk a continuation of the war on tribal or political grounds in the future, even if they win autonomy or separation.”

She fought for accountability and justice. These calls were ignored in 2005, when the region, the US, the UK and Norway mediated the peace deal that was to lead to South Sudan’s secession and included a de facto amnesty that permitted impunity for the terrible crimes. As mediators press South Sudan’s leaders for peace today, they should bear in mind Jemera’s wise counsel.

Even as they tried to deny her findings, commanders and politicians respected her commitment, intellect and courage. “That crazy redhead”—so described by one Ugandan leader who found himself on the sharp end of her allegations—will be deeply missed.