Tighter economic integration with China should not be a reason to delude oneself about the nature of a regime that is profoundly adverse to democracy, writes Nicholas Bequelin.

Is the Australian Government trying to manufacture a false sense of security among the public about what increasing reliance on China really means for the country's future?

It's hard to see what else could have led Prime Minister Tony Abbott to publicly declare his elation at the prospect at China becoming "fully democratic by 2050" during an effusive state dinner last month.

The reality is that the Chinese Communist Party - which has shed communist ideals but not its Leninist organisational principles and insistence on one-party rule - has no intention to embrace democracy, now or later. In fact, what the Party states unequivocallyis that one-party dictatorship is both "more suited" to the Chinese people and superior to democracy.

This is not to say that Chinese people - as opposed to their autocratic leaders - don't want a democratic and accountable government under the rule of law. The Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo, for instance, was a long-standing advocate of the democratisation of China. The appeal of his ideas among many is precisely why he is serving an 11-year sentence in a remote prison. Even more modest reformers, such as legal advocate Xu Zhiyong, who put forward the idea that citizens should lead China's transition towards genuine rule of law, inevitably end up behind bars.

Hundreds of other political prisoners can attest to the Party's deep antipathy to the idea of external checks and balances, not to mention sharing power in any way or form.

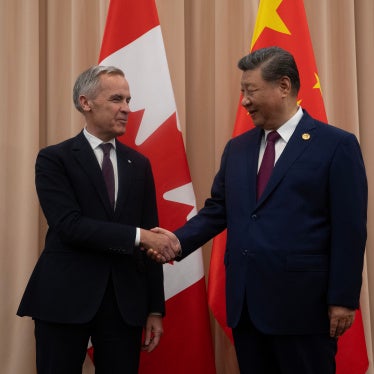

In fact, if Tony Abbott hadn't been so giddy about the Free Trade Agreement with China, he might have noticed that President Xi had said in his speech to the Parliament that China remains committed to the socialist path: code for continued one-party dictatorship.

But being delusional about China seems to be a bipartisan condition. At President Xi's address to Australian Parliament, Australia's Labor Opposition Leader, Bill Shorten, said:

"We all take heart from the fact that decades of economic growth and trade liberalisation have encouraged the real and important advancement of human rights, political freedoms and the rule of law and long may that continue."

The truth is that China is in the midst of one of the harshest crackdowns on critics and rights activists witnessed in years, not to mention active and overt political censorship of media and internet content, persecution of religious believers who refuse to join state-controlled churches, large-scale forced-evictions to make way for infrastructure projects, and repression of ethnic Tibetans in Tibet and Uighurs in Xinjiang.

Chinese leaders have also taken a hard line on democratic aspirations in Hong Kong, reneging on China's formal promise to introduce universal suffrage for the election of the chief executive.

And while there are many unknowns about the Chinese economy, the extent of corruption, hidden protectionism, absence of real financial markets, lack of independent courts, systemic corruption, and rampant theft of intellectual property are not among them.

So how can we account for comments that are so far off the mark, about a country to which Australia's economic future is so closely linked?

One may wish it was another case of commercial interests speaking, but in reality the problem goes much deeper: after years of finding justifications for not taking up human rights issues publicly with China, the Australian Government has ended up believing its own - and China's - propaganda about "the human rights situation improving overall", "encouraging signs", and, above all, that "human rights matters are best raised in private meetings".

The bilateral "human rights dialogue" between Australia and China is how these issues are disposed of; a sporadic, behind closed doors meeting in which nothing of substance is discussed, and whose main function is to quarantine human rights issues from regular and high-level diplomatic relations. Abbott has acknowledged this himself, stating that "these human rights matters are matters for the human rights dialogue. They are not normally matters for discussion between Prime Ministers and Premiers or between Prime Ministers and Presidents."

So far the main result of the dialogue seems to have been that Australia is now parroting China's position on a wide-range of human rights issues, while China doesn't seem have ever conceded anything, and actually keeps detaining Australian citizens of Chinese origin embroiled in business disputes on the mainland.

Yet in what must have felt like an unprecedented act of courage, Canberra expressed publicly earlier this year "concerns" about the arrest of Pu Zhiqiang, a prominent Beijing lawyer with a record of handling politically sensitive cases who is facing imminent trial. A few months later, China agreed to the Free Trade Agreement, proof that when Australian leaders can find their voices, the sky doesn't fall.

Tighter economic integration with China should not be a reason to delude oneself - and the country - about the nature of a regime that is profoundly adverse to democracy, at home and abroad. Instead, it should be an opportunity for the Australian government to speak clearly and consistently on human rights.

Nicholas Bequelin is senior researcher in the Asia Division of Human Rights Watch, based in Hong Kong. Follow him on Twitter @bequelin. View his full profile here.