Summary

This submission highlights a number of key areas of concern regarding Italy’s compliance with its international human rights obligations. They concern migration and asylum policy, an inadequate state response to violence against migrants and Roma and Sinti, and international justice.

Status of implementation of first cycle recommendations

We note with satisfaction that Italy ratified the Optional Protocol of the Convention against Torture on April 3, 2013, though Italy has yet to establish or designate a national prevention mechanism, nor has it incorporated into domestic law the crime of torture as defined in article 1 of the Convention against Torture. At this writing, a bill to do the latter is pending in parliament. We regret that Italy has yet to fulfill its pledges to ratify the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances and to establish a national human rights institution in accordance with the Paris Principles.

Migration and Asylum Policy

Summary returns to Greece

Italy summarily returns to Greece adults and children who are detected after stowing away on ferries traveling from Greek ports to Italy. Italian border police at the Adriatic ports of Ancona, Bari, Brindisi, and Venice fail to screen adequately for people in need of protection. As a result, unaccompanied children and adult asylum seekers are summarily sent back to Greece.

During its previous UPR in 2010, Italy had accepted recommendations to “review its legislation and practices, ensuring that they comply fully with the principle of non-refoulement.” However, these summary returns violate Italy’s obligations under national, European, and international law to ensure access to a fair asylum procedure and protection against refoulement, as well as the prohibition of expulsion of unaccompanied children. Summary returns to Greece of asylum seekers contradict Italy’s stated policy of assessing carefully the risk of rights violations before doing so, in light of overwhelming evidence of chronic problems with Greece’s asylum system and detention conditions and a European Court of Human Rights ruling that the transfer of an Afghan asylum seeker from Belgium to Greece constituted a violation of fundamental rights.

During its previous UPR, Italy also accepted the recommendation to “adopt special procedures to ensure the effective protection of the rights of unaccompanied children in their access to asylum procedures.” However, safeguards at Italy’s Adriatic ports against such returns are inadequate. Unaccompanied migrant children and adult asylum seekers undergo inadequate or non-existent screening that fail to determine age or to inform them about their rights. NGOs within the ports are not given adequate access to incoming migrants in order to assist them.

Conditions and treatment on board ferries during return journeys can be highly problematic. Seventeen out of twenty-nine returned migrants and asylum seekers interviewed by Human Rights Watch in 2012, including unaccompanied children, complained of being confined in poor conditions with inadequate food, water, and sanitation on board ships. Under international human rights law, Italy has the primary responsibility to ensure that returning migrants’ rights are upheld.

Both the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights Nils Muižnieks, in September 2012, and the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of migrants Francois Crépeau, in May 2013, have urged Italy to refrain from summary returns to Greece, citing continuing concerns over the grave deficiencies in Greece’s asylum system. In November 2013, 19 people, including 8 minors, as well as Syrian nationals, filed a complaint against Italy with the European Court of Human Rights for violations of their right to protection against refoulement and collective expulsions, as well as the right to an effective remedy for summary returns to Greece between March and October 2013. The application was pending at this writing.

Boat migration

Italy is subject to fluctuating levels of boat migration across the Mediterranean. Over 42,000 migrants reached Italy by sea in 2013, a significant increase over the previous year. After over 500 people died in two shipwrecks off Italian coasts in October 2013, and criticism that disputes between Italy and Malta had led to delays in rescue responses, Italy launched a naval search and rescue operation called Mare Nostrum. According to media reports citing the Italian interior minister, as of mid-August 2014 the operation had rescued more than 70,000 people. There is inadequate support from the EU and other EU member states for this vital operation, despite calls by the Italian authorities for the EU border agency Frontex to assume responsibility for it and a deteriorating security situation in Libya, the main transit route for boat migration to Italy.

Italy rightly renounced its 2009 policy of interdicting and summarily returning migrant boats to Libya following a 2012 ruling by the European Court of Human Rights that such returns violated its nonrefoulement obligations. There were two known instances in 2013, however, in which Italian authorities instructed commercial vessels to disembark in Tripoli persons rescued off the Libyan coast. In one of those cases, the commercial vessel contradicted the order and Italy eventually allowed the persons to be disembarked on Italian territory (after Malta, the vessel’s destination, refused). In the other case, the persons were disembarked in Libya, a country that lacks a functioning asylum system and where migrants are at risk of arbitrary arrest, ill-treatment, and exploitation.

Reception and integration measures

A video filmed at the reception center on Lampedusa in December 2013 showing a naked man being hosed down while others waited in line highlighted concerns about inadequate reception facilities and conditions for migrants and asylum seekers. Human rights groups and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees have for years pointed to Italy’s poor reception conditions, abusive treatment in detention and reception facilities, and lack of integration measures for recognized refugees. Italy has largely failed to implement a long-term approach for asylum seekers and refugees, adopting instead short-lived “emergency plans” that do not guarantee consistent, adequate standards of treatment, conditions, and access to asylum.

This emergency approach has led to different types of structures for asylum seekers and recognized refugees, with significant disparities in quality and programs. First reception centers, such as the one on Lampedusa, are often overcrowded (a problem exacerbated by a chronic failure to transfer people quickly to more appropriate mainland facilities). While Italy is moving toward the use of smaller centers, large camps are still operating in different parts of the country, with serious problems with respect to infrastructure and management. The center in Mineo, Sicily, for example, houses over 4,000 people. The center was established in 2011, under the auspices of the North Africa emergency plan, and was designed to accommodate only 2,000 people.

The System for the Protection of Asylum Seekers and Refugees (SPRAR)—a network of small, specialized centers—was recently expanded to allow for an increase from 3,000 places to over 13,000 by 2016. The increase, while welcome, may not be sufficient. The lack of state support has led many asylum seekers and refugees to occupy abandoned buildings, such as the “Salaam Palace” in Rome, where over 1,000 people (including women and children) were squatting in deplorable conditions at this writing.

Problematic reception and integration measures in Italy have led courts in Germany to block returns to Italy under the Dublin Regulation (European Union rules assigning responsibility to the first country of entry to process asylum claims). In February 2014, the UK Supreme Court ordered a lower court to reexamine arguments by four asylum seekers that they run the risk of inhuman treatment if returned to Italy under the Dublin Regulation, rejecting a UK government argument that Italy can be presumed to be safe for such returns. Council of Europe Commissioner Muižnieks has repeatedly urged EU member states to refrain from conducting Dublin returns to countries whose asylum systems are either overstretched or highly dysfunctional, including Italy.

Immigration detention facilities

Following a 2011 change, Italian law allows for immigration detention for up to 18 months in Identification and Expulsion Centers (CIE), the maximum duration allowed under EU law. These closed facilities are generally not suited for long-term stays, and material conditions and access to recreational activities, appropriate healthcare, and legal counsel (including for the purpose of applying for asylum) vary significantly. Nongovernmental organizations and international human rights bodies have raised serious concerns. The Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights noted in a 2012 report that a significant number of detainees in CIEs are foreign nationals convicted of criminal offences who were remanded into immigration detention upon release from prison pending deportation from Italy. He urged Italian authorities to begin deportation proceedings before their release from prison. In April 2013, the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of migrants criticized substandard conditions and inadequate access to justice in the CIE.

Detainee protests in CIEs are common. At this writing, eight out of thirteen CIEs were temporarily closed, including for repairs of damages caused by protests, while five others were operating at reduced capacity. According to official statistics, 6,016 people were detained in CIEs in 2013. Of these, only 2,749, or less than 50 per cent, were actually expelled.

The Italian government has indicated its intention to reduce the maximum period of immigration detention; at this writing the details of the possible reform and its timeline remained unclear.

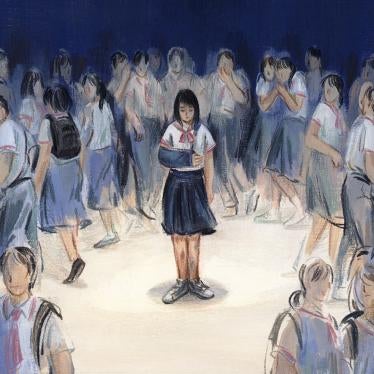

Inadequate State Response to Attacks on Migrants and Roma and Sinti

While Italy accepted the numerous recommendations made during its last UPR in 2010 regarding effective measures to combat discrimination, racism, and xenophobia, including more effective investigation and prosecution of hate violence as well as comprehensive measures to counter hate discourse and intolerance, progress towards full implementation of these recommendations has been slow.

Racism and xenophobia towards migrants, Roma and Sinti, characterized by violence as well as offensive political discourse, are a serious problem in Italy. Immigrants, Italians of foreign descent, and Roma and Sinti have been victims of brutal attacks in recent years, both in mob violence and individual attacks. At the same time, prosecutions for racially-motivated attacks are rare, due to a narrowly-drafted hate crime statute and insufficient training of law enforcement and judiciary personnel. Incomplete data collection compounds the problem.

Italian criminal law provides for enhanced penalties of up to one-half for perpetrators of crimes aggravated by racist motivation. The restrictive wording of the statute, which speaks of racist or hate “purpose” rather than “motivation,” and its failure to acknowledge explicitly the possibility of mixed motives, have given rise to narrow interpretations by the courts and limited applicability in practice. The approach of courts appears to be evolving, with the aggravating circumstance provision being used effectively when racist animus is the sole motivation for an assault, but the racist dimension of a crime is downplayed or ignored altogether when the alleged perpetrator(s) appear to have other, additional, motives. The fact that only one person was convicted of an attack on a migrant during the harrowing violence targeting sub-Saharan African seasonal migrant workers in Rosarno in January 2010 reflects the challenges.

Italy has taken some steps to improve its response to these issues since 2010. The government invited the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (OSCE/ODIHR) to implement training programs to improve detection and investigation of hate crimes, including racist violence.

Xenophobic and racist discourse, including by elected officials and other public figures, contribute to a climate of intolerance. Former minister of integration Cécile Kyenge, a naturalized Italian citizen originally from Congo, was the object of relentless racist insults during her ten-month tenure (the post was eliminated by the new government in February 2014). This included, notably, the vice-president of the Italian senate comparing the minister to an orang-utan. Though widely criticized for his comment, he remains vice-president of the senate. While freedom of speech is a hallmark of a democratic society, public figures have a special responsibility to uphold the equally fundamental values of equality and non-discrimination; they should face political and social censure for hate speech.

The government launched in July 2013 consultations towards the development of a National Plan against Racism; at this writing, the plan had not yet been submitted for adoption. It remained unclear whether the plan would include specific measures to address xenophobic and racist violence.

International Justice

As a state party to the Geneva Conventions, the Convention against Genocide, the Convention against Torture, and the International Criminal Court treaty, Italy has made international commitments to contribute to the fight against impunity for the worst crimes, such as war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide.

In addition to diplomatic support to international justice in its foreign policy, Italy should take concrete steps at the national level to ensure that it does not become a safe haven for suspects of war crimes or torture committed in third countries.

Italy should urgently consider following the precedent set by an increasing number of European and non-European countries which have established institutional arrangements ("war crimes units") within their national immigration and justice systems to identify and investigate suspects of these crimes.

Recommendations

Regarding migration and asylum policy, Italy should:

- Suspend immediately summary returns to Greece, as recommended by the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights and the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of migrants;

- Ensure that all migrants who express a wish to apply for asylum are given access to the territory and a meaningful opportunity to register their asylum claim and present their case;

- Permit those reaching Italy who claim to be unaccompanied children, without exception, to stay and be given access to a proper age determination process, a guardian, and a best interests determination;

- Continue the vital Mare Nostrum operation and continue to seek wider EU support for it;

- Ensure that persons interdicted or rescued at sea have access to a fair procedure, in Italy, for determining protection needs, including asylum and subsidiary protection;

- Adopt protocols to ensure that Italian authorities are not involved in refoulement of persons rescued at sea by commercial vessels;

- Ensure adequate conditions, activities, access to legal counsel, and healthcare in reception centers for asylum seekers and in immigration detention facilities; and

- Enhance the use of alternatives to detention for irregular migrants subject to expulsion, and ensure that only persons with a reasonable prospect of expulsion are detained, and that any such detentions should only be when necessary and for the shortest amount of time reasonable to achieve the purpose of expulsion.

Regarding combating violence against migrants and Roma and Sinti, Italy should:

- Reform criminal law to ensure that the aggravating circumstance of racist motivation allows for mixed motives and application of enhanced penalties where violence has been committed “in whole or in part” due to bias;

- Ensure obligatory and consistent training for law enforcement personnel on detecting, responding to, and investigating crimes motivated wholly or in part by racial, ethnic or xenophobic bias;

- Ensure obligatory and continuous training for public prosecutors on relevant national legislation, in particular the aggravating circumstance of racial motivation, as well as European and international standards;

- Condemn forcefully and consistently, at the highest levels, all racist and xenophobic statements, especially by public and elected officials, and make clear that racist discourse has no place in Italian society; and

- Ensure the timely adoption of a comprehensive National Plan against Racism, including specific measures to address xenophobic and racist violence, with a budget allocation and clear responsibilities for various ministries and agencies tasked with implementing the plan.

Regarding international justice, Italy should:

- Increase its efforts to conduct investigations and prosecutions of international crimes in accordance with international law, including by setting up a specialized war crimes unit within its national judicial system.