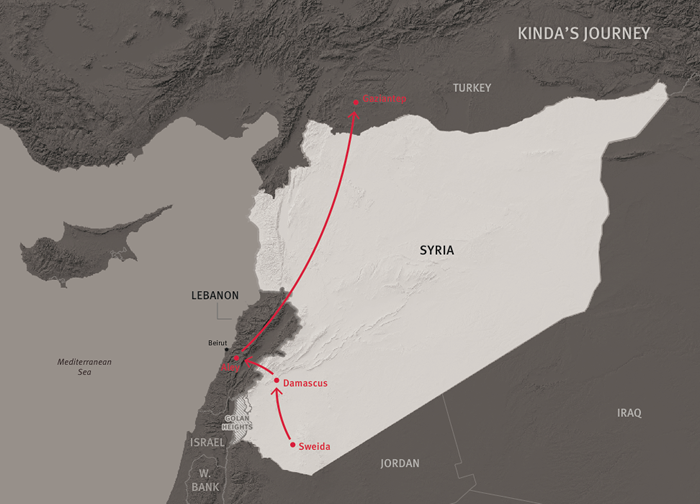

After surviving detention in Syria, a flight to Lebanon, and a move to Turkey, Kinda, a Syrian activist and refugee, was facing a new kind of terror – death threats.

She explained this to the Human Rights Watch researcher Hillary Margolis as they sipped tea in a dimly lit room off the courtyard of a Turkish café, surrounded by dark wood furniture and richly colored pillows. Although Kinda appeared intimidating at first, with her wild, curly hair and dramatically drawn eyebrows, when she spoke her demeanor was surprisingly gentle.

It’s her own cousins and extended family members who are threatening to kill her, she said, for falling in love with and marrying a man from a different religious background. Kinda is a member of Syria’s Druze minority, and her husband, Ali, also a refugee from Syria, is Sunni. With Kinda four months pregnant and scared, she told Hillary, they had little choice – she and Ali needed to leave Turkey.

Kinda’s journey has been winding, chaotic and tinged with danger, as for many women fleeing Syria. A new Human Rights Watch report, “We Are Still Here,” shows that, like Kinda, many of Syria’s women are more than just victims of the conflict. Some are activists or aid providers, caring for the sick or those in need, often at great personal risk. Like men, they have not been spared the brutality of Syria’s conflict: they face the threat of arbitrary arrest and detention, harassment, physical abuse and even torture by government forces and in some cases non-state armed groups.

In many cases, Syrian women’s roles are changing. They’re becoming de facto household heads or primary providers because their male family members have been detained, injured, or killed, or simply as a result of economic circumstance in refugee and displacement settings. Moving forward, women’s voices should be heard, including through meaningful participation in peace negotiations, local decision-making bodies, and in determining Syria’s future.

Originally from the primarily Druze city of Sweida in southwestern Syria, Kinda lived most of her life in Damascus, where she worked in a ticketing office for a tourist agency. It was the government’s May 2012 offensive in Houla that killed over 100 residents, most of them women and children, that drove Kinda, then 26, to begin protesting.

Over the next few months, Kinda, her younger sister Lubna, and their friends staged protests in both Damascus and Sweida, an area known for its support of President Bashar al-Assad. Her family was supportive of her activism. Her father had opposed Assad’s government since the 1980s, and her mother sewed banners and flags for their protests.

In November 2012, they staged their most attention-grabbing protest yet, she said. Kinda, Lubna and two female friends had sewn white wedding dresses, symbolizing a return to day-to-day life in Syria. They would hold the protest in the crowded Medhat Basha market in the old city of Damascus, a community and social hub where people could buy everything from dried fruit to clothing. Before they left home for the protest, their father gave them advice: If you get arrested, don’t worry, just be careful and take care of yourselves.

Kinda felt scared as they walked into the market, all four women wearing the hijab (headscarf) and abaya (long, loose-fitting robe). But when they took these off to reveal white bridal dresses underneath, Kinda said, she felt happy and strong, like no one could stop them. They walked slowly through the market, holding up signs with messages such as, “We declare an end to military action in Syria,” and “You are tired, we are tired, we need another solution.” They called themselves the “Brides of Peace.”

Within 30 minutes, they were arrested by government security forces and then taken to a detention facility. Since they were expecting that could happen, and that they’d be forced to take off the wedding dresses, they had worn jeans and t-shirts underneath.

“Who made you do this?” Kinda said the officers repeatedly asked, expecting that as a Druze, like members of many other religious minorities in Syria, she would support Assad. One officer spit on her.

The hours ticked by, and the interrogations became more intense. One officer threatened to arrest and torture her father, Kinda said. He also threatened to call her community leaders, the sheikhs, and tell them that she and her sister were working as prostitutes – to destroy their reputations, and their family’s. Then, the officer told an investigator to bring him “an electricity instrument.”

The women were taken to another floor in the detention center, where blood streaked the floors and walls. There, an investigator in a green military uniform beat Kinda’s hands with a bundle of four electric cables while she screamed with pain.

Kinda was jammed into a cell measuring about 3 square meters with 23 other women. She and the other women arrested with her were repeatedly sexually harassed and threatened, but did not experience further torture, she said – likely because of the media attention their arrests received. The other women in their cell came back from interrogations bloody and bruised.

She lived in that tiny cell for a month and a half. She and the other Brides of Peace were freed on January 9,, 2013, in a prisoner swap.

But back in Sweida, everything had changed. The government had closed her father’s restaurant and forced her parents and brother from their home. Now identified as anti-government, the family was shunned by their community. Afraid of the government, after three months they fled to nearby Daraa, a predominantly Sunni area where protests had erupted in March 2011. They were hardly safer there: an extremist Islamist group, which Kinda identified as Jabhat al-Nusra, kidnapped Kinda’s father and brother and held them for five hours because they were Druze. Within two weeks, the family fled to Lebanon. There, they rented an apartment in the mountainous Druze town of Aley. They survived on donations, but it was hard. They found Lebanon expensive, and there were tensions between the Lebanese and the ever-increasing number of Syrian refugees.

Seven months later, a nongovernmental organization offered to bring Kinda to southern Turkey to attend a workshop for activists. There, in a café frequented by Syrian refugees, Kinda met Ali, who came from rebel-held parts of Aleppo. They fell in love and married one month later. Her parents and siblings, who had followed her to Turkey because of the country’s relative security compared with Lebanon, were happy for her, despite the pair’s cultural and religious differences.

Kinda and Ali live in Gaziantep, Turkey, where Ali has found temporary work. They had been sleeping on friends’ couches, but recently a friend found them an apartment to rent. Her sister Lubna is married and living in Istanbul, but Kinda worries about her parents – her mother sews for money, but her father can’t find work in Turkey.

It’s the death threats that scare her the most, though. They come from her extended family, including cousins, who are angry that Kinda married outside of the Druze community. The threats come in text messages, phone calls, and Facebook posts, and say things like: “We will get to you. You can’t escape us.”

Because of the war, much of Kinda’s extended family has left Syria for Lebanon and even Turkey, she said – too close for comfort. Also, those cousins still in Syria could reach her through contacts in Turkey. Kinda doesn’t feel safe leaving the apartment. She’s mentally and emotionally tired, she said, and she feels like she and Ali are living a temporary life, like nothing is stable. She’s excited about her baby, but she’s scared and worried, too. She and Ali want to move far away, somewhere they can feel safe, to start yet another chapter in their lives.

The international community can do more, in terms of aid, refugee programs, and justice, to help Syrian refugees like Kinda.