Summary

[331] is like, “no, you’re NYCHA,” but then when you call NYCHA, they’re like, “No, you’re that Reliant [the property management company].” So you’re falling in between and you’re in this grey area where it’s like, “where am I?”

– Jessica Devalle, Resident at Independence Towers, a building which transitioned to private management under NYCHA’s PACT program…

Around 2 million people in the United States call public housing home. Owned and typically operated by government entities, it is a crucial source of deeply affordable and stable housing for low-income individuals, and particularly for people of color, single mothers, people with disabilities, and older people. Yet over the last 20 years, the federal government has dramatically slashed annual funding for repairs and everyday operations.

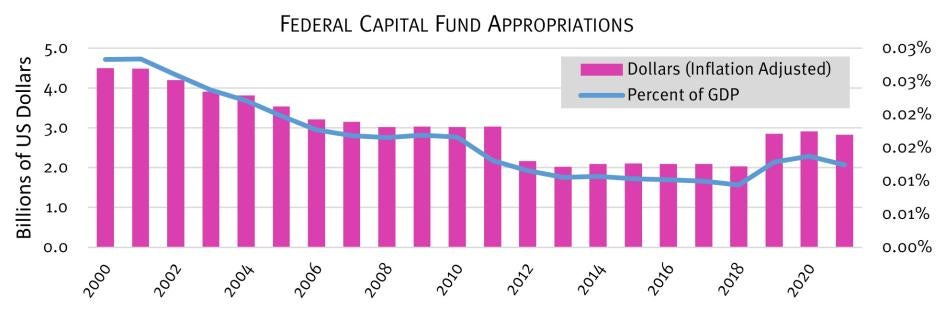

In 2021, the overall budget of the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) was $69.3 billion, of which $2.9 billion was allocated for major repairs to public housing. Adjusted for inflation, this amount is around 35 percent lower than the capital funding allocation in 2000, which in 2021 dollars would be worth $4.5 billion

These cuts have severely impacted both the availability and the habitability of housing. It has forced residents to live with heating system and plumbing failures, water leaks, pest infestations, peeling lead paint, and harmful mold. Years of deferred maintenance has caused the cost of repairing these homes to skyrocket. Each year, between 8,000 and 15,000 units of public housing in the US are lost to deterioration.

Rather than urgently invest in saving these homes, Congress has continued to steadily divest from public housing while increasing funding for housing programs that rely on the private sector. This shift is expressed in the 1998 Quality Housing and Work Responsibility Act (QHWRA), which introduced sweeping reforms, including doing away with a requirement to replace each public housing unit demolished with a new one. The QHWRA also amended the original preamble to the 1937 US Housing Act, which largely started the United States’ modern public housing program, and which declared the policy of the US to be “to assist the several States and their political subdivisions to . . . remedy the unsafe and insanitary housing conditions and the acute shortage of decent, safe, and sanitary dwellings for families of low income.” The QHWRA, by contrast, proclaimed that the role of government would be to “promote and protect the independent and collective actions of private citizens to develop housing.”

However, many very low-income families continue to rely on public housing. For example, New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) accounts for over half of all homes affordable to those in New York City with incomes at or below 30 percent of the area’s median income, whom HUD classifies as “extremely low income.” To maintain the habitability of their homes, local housing authorities have been forced to turn to alternative financing strategies. One of these strategies is a federal program called the Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD), that allows housing authorities to convert their public housing to more stable subsidy programs that are typically used to finance private-sector affordable housing, allowing them greater access to private financing.

This report documents the implementation of this program by NYCHA, which has by far the largest public housing stock in the country. Under the program, rebranded as Permanent Affordability Commitment Together (PACT), NYCHA has privatized the management of a portion of its housing developments and leased those buildings to private developers, giving them a direct stake in the revenue public housing generates.

Examining this program is of particular importance at this moment, as the Covid-19 pandemic has shone a light on the extent of financial precarity and housing insecurity in the United States. Millions of tenants across the country have fallen behind on rent as a result of the pandemic’s economic impacts, and the populations served by public housing have been hit especially hard. In August 2021, the US Supreme Court deemed the federal government’s eviction moratorium unconstitutional while New York state has sought to maintain protections for tenants with an eviction moratorium that extended until January 15, 2022.

Rents in US public housing are federally capped at 30 percent of a household’s income, but this can still place a significant burden on residents with very low incomes. Many still fall behind on rent, putting them at risk of being displaced once eviction protections expire. As of October 202o, NYCHA reports that nearly 40 percent of NYCHA households are in arrears.

Based on research conducted between October 2020 and October 2021, this report finds that PACT has negatively impacted the right to housing of low-income residents by leading to a reduction in oversight and crucial protections for tenants’ rights, including the loss of a federal monitor overseeing a previous settlement with NYCHA. Inadequate government oversight and avenues for redress may render tenants more vulnerable to other violations of their rights, such as increased evictions leading to a loss of housing or ongoing habitability issues.

With NYCHA converting its first building under PACT in late 2016, PACT is a relatively new program, and various factors make it difficult to draw clear conclusions about the long-term impacts of PACT on evictions and habitability. Many PACT conversions occurred while a moratorium on evictions was in place due to the Covid-19 pandemic, and as such, the impact of these conversion on evictions is unknown. PACT has led to buildings receiving sorely needed upgrades and repairs, alleviating maintenance issues that plagued the buildings when managed by the cash strapped NYCHA. However, the ability of new private managers to adequately maintain the buildings will become most clear as PACT buildings age and their now-new systems themselves require upgrades of replacement.

Despite the difficulties of drawing clear long-term conclusions about the impacts of PACT on tenants, the report documents apparently significant increases in evictions in two developments which together house 6,500 people. In addition, tenants Human Rights Watch interviewed described various concerns in PACT developments, such as feeling pressured into signing leases without fully understanding them, ongoing habitability issues and potentially dangerous construction practices, a lack of access to services, and difficulties in obtaining redress in several developments. PACT developers generally disputed these claims, but they underscore the importance of effective oversight and redress mechanisms.

Most conversions took place just prior to or while the eviction moratorium has been in effect. The increase in evictions in two developments, combined with the reduction in oversight and protections for tenants under PACT, raises concerns about the possibility of a new wave of evictions following the end of the moratorium.

What is RAD?

RAD was a program developed by HUD in response to consistently inadequate congressional appropriations and was authorized by Congress in 2012. Conventional public housing is funded by annual grants under Section 9 of the US Housing Act, but RAD allows PHAs to “convert” housing from Section 9 to subsidies under Section 8 of the Housing Act. Section 8 is typically used to subsidize private sector low-income housing and provides for both “tenant-based” and “project-based” rental assistance. For tenant-based assistance, tenants receive vouchers that they can use to find housing on the private market. For project-based assistance, HUD enters into long-term contracts with owners of specific housing complexes, providing a subsidy that covers the gap between what a tenant can afford and the “market rent” of that housing. RAD utilizes project-based Section 8 subsidies.

While both Section 8 and Section 9 are subject to annual congressional appropriations, Congress has, especially since 2000, chosen to increase appropriations to subsidize private housing under Section 8 while at the same time reducing public housing funding under Section 9. Switching to Section 8 also allows PHAs to better access private financing, as well as other public subsidies which are typically reserved for the private sector. While this enables PHAs to access financing for long-underfunded housing, in some cases, it has led to significant private-sector involvement in the operation and financing of public housing. Some PHAs have used RAD to transfer ownership and management of their housing to private entities, which in turn profit from the rents and federal subsidies.

NYCHA utilizes RAD in a program called Permanent Affordability Commitment Together, or PACT. Under PACT, NYCHA leases some of its public housing to private developers for 99 years and outsources the management of these developments to private companies.

Despite the concerns of various housing advocacy organizations that there has been insufficient oversight of RAD’s impacts on tenants, Congress has chosen to expand the program rather than sufficiently fund public housing directly. Congress originally capped the total number of homes eligible for RAD at 60,000 nationally, but has repeatedly increased this limit, which now stands at 455,000, or about 40 percent of all public housing apartments in the US. Beginning in 2016, NYCHA has utilized RAD to privatize the management of around 9,500 apartments, and ultimately plans to “convert” one-third of its public housing — home to as many as 136,o00 people — under PACT.

Despite being promoted as a way to attract private dollars to repair public housing, public money is crucial to financing RAD deals. HUD has, previously, touted leverage ratios (i.e., how many dollars of external financing is raised for each dollar of RAD subsidy) as high as 19:1. However, after the Government Accountability Office (GAO) criticized their methodology, HUD’s reevaluation found that for every $1 of publicly held or subsidized funding, just $0.29 of in private, unsubsidized financing was raised.

Insufficient Oversight and Loss of Specific Protections

The conversion of properties to PACT has been accompanied by insufficient oversight and has resulted in the loss of several specific protections that apply to NYCHA housing.

Following a lawsuit brought by the federal government concerning the dire conditions in NYCHA housing and NYCHA’s systematic underreporting of those conditions, NYCHA agreed to a settlement that instituted a federal monitor to oversee the authority’s compliance with federal law. The settlement agreement set out a number of reporting and compliance requirements regarding mold remediation, lead paint abatement, elevator and heat outages, and pest infestations. The monitor has enforcement powers and can order remedial directives in the event that NYCHA fails to comply with its obligations under the agreement. But PACT properties are largely exempt from the obligations of this monitor agreement.

In addition, following a lawsuit brought by tenants alleging that NYCHA had a pattern or practice of miscalculating residents’ household income and overcharging them for rent, NYCHA entered into a settlement agreement which will institute various eviction protections starting in January of 2022 and lasting for three years. In particular, NYCHA will be prohibited from starting an eviction proceeding either while a resident’s request that NYCHA adjust its rent calculation due to a loss in income is pending or while a resident has an open grievance concerning NYCHA’s rent calculation. This settlement does not apply to PACT properties.

Tenants’ legal recourse in PACT properties is insufficient. PACT tenants can bring cases under New York’s landlord-tenant law and have enforceable rights under PACT leases which provide procedural protections from eviction and which prohibit eviction unless there is “good cause.” However, tenants cannot enforce the NYCHA and PACT developers’ obligations under the contracts underlying PACT transactions. These contracts contain a number of key provisions concerning resident rights as well as obligations on PACT partners to make needed repairs to tenants’ apartments. When residents sue to obtain repairs, NYCHA has tried to disclaim its responsibility for ensuring that maintenance is carried out in PACT developments.

Evictions

Many NYCHA residents are concerned about how involving private companies in the operation and financing of public housing will impact them. “Monopoly is being played with our lives,” said Cesar Yoc, a NYCHA resident in the Bronx, referencing the multi-player economics-themed board game. “That’s what the fight is, to protect us from investors who don’t give an ‘F’ about us.” On paper, aside from the NYCHA-specific protections discussed above, tenants in RAD housing nationally have essentially the same rights as those in public housing. But in practice, property managers have significant discretion over evictions and other decisions that may have far-reaching impacts on tenants’ lives. Many tenants worry that PACT managers will be more likely to evict them if they fall behind on rent, which could lead to homelessness or a loss of adequate housing. “This is much different than NYCHA, private management means they can boot you when they want,” Donovan Richards, Queens Borough President, warned NYCHA residents during a presentation on RAD.

NYCHA does consistently and publicly disclose comprehensive eviction data, either for its own buildings or in PACT housing. In response to a request from Human Rights Watch, NYCHA provided data indicating that two of the six PACT conversions — which together account for nearly half of the apartments converted before February 2020, one month before New York enacted a moratorium on evictions — saw substantial increases in evictions after conversion.

The other four PACT conversions were not associated with higher evictions, and it is not possible based on the existing data to draw conclusions about whether PACT conversions are generally likely to lead to more evictions. Nonetheless, these cases offer a cautionary tale about ways in which the process of conversion could lead to negative impacts on housing rights if adequate safeguards and oversight aren’t built into the program.

At Ocean Bay (Bayside), which is home to over 3,700 people and comprises around 15 percent of all PACT converted homes, multiple residents told Human Rights Watch that the new private management was more aggressive concerning eviction. They “put you out faster,” one resident said. Eviction data from NYCHA and the PACT developer for Ocean Bay indicate that eviction rates increased in the years following conversion, and that eviction rates for both for non-payment and other reasons are significantly higher than the NYCHA average. Data for one other large conversion, Betances in the Bronx, indicate that evictions increased post-conversion.

RDC Development LLC, the PACT developer for Betances and Ocean Bay (Bayside), told Human Rights Watch that, before a household is evicted, they work with residents on a case-by-case basis to “set up payment plans and refer residents to programs that can provide assistance for rent or other expenses.”

It is hard to evaluate the full effect of PACT, given the number of sites and the variety of entities involved, and because nearly half of all apartments converted either immediately before or during the Covid-19 pandemic, when an eviction moratorium was in place. But the elevated eviction rates in two developments raise concerns as to whether there are adequate safeguards to mitigate the risk of increased evictions that result in homelessness or are otherwise inconsistent with international human rights standards

The economic recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic has been unequal, with low-income people still severely affected by the downturn. Residents in PACT developments could be especially vulnerable to losing their homes following the expiration of the moratorium on January 15, 2022. The lack of more affordable housing options means that many tenants face homelessness if they are evicted.

Housing Conditions

The purpose of RAD is to reverse public housing’s slide into dilapidation due to chronic underfunding. NYCHA has faced mounting problems with peeling lead paint, failing heat systems, and harmful mold, which can exacerbate respiratory health conditions such as asthma. In some PACT developments, residents told Human Rights Watch that their living conditions improved. However, others reported that serious issues persist.

Some residents told Human Rights Watch that they are still dealing with failing heat. Others described repairs being carried out in an unsafe manner, potentially exposing residents to lead paint or asbestos. Others said that renovations were done cheaply and worry that their homes will soon fall into disrepair. “I don’t know if their issue is also money? Somehow, they are still being frugal, I guess,” Sonyi Lopez, a PACT resident in the Bronx, said. PACT developers generally disputed these claims in response to questions by Human Rights Watch.

It is not possible based on the findings of this report to draw conclusions about the overall effect of PACT conversion on housing conditions, but tenants’ expression of concerns underscores the importance of ensuring effective oversight and accountability mechanisms to address them.

The Process of Conversion and Affordability

Several tenants described the PACT conversion process as rife with confusion. Some of the residents Human Rights Watch interviewed said they did not understand their lease terms and were not provided with either translated drafts of leases or a copy of what they signed, though each PACT developer that Human Rights Watch questioned about translations stated that draft leases were provided in multiple languages.

After conversion, PACT tenants no longer have access to the same NYCHA resources or federal oversight mechanisms, leaving many residents struggling to make complaints, request repairs, or obtain emergency transfers due to crime or abuse. Many PACT tenants stated that they either lost their social service providers or that such providers were either nonexistent or had little presence at their development. “I called my social worker [at NYCHA] and she told me that she had nothing to do anymore with this building,” one PACT resident in Manhattan said. All PACT developers told Human Rights Watch that residents at PACT developments had access to social service providers.

Fulfilling the Right to Adequate Housing

Adequate housing is a human right guaranteed by the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). The United States has signed, but not ratified, the ICESCR, meaning that the US government is obligated to refrain from actions that undermine its object and purpose.

US policy has persistently undermined the right to housing by reducing funding to both public housing in particular and to all forms of housing assistance generally. People with low incomes in the US face persistent shortages of affordable housing, as the federal budget authority for all low-income subsidized housing programs is lower today than it was in 1978. As a result, the US needs millions more affordable homes to meet the needs of low-income households. Nationally, applicants spend an average of 21 months on a PHA’s waitlist before being accepted into public housing, but steep cuts have resulted in homes that are unsafe or unfit for those lucky enough to receive assistance.

Under the ICESCR, governments should take steps to fully realize the right to housing, and “retrogressive measures,” such as funding cuts to housing programs, need to be fully justified. Especially given the increasing need for affordable housing in the US and the federal government’s failure to provide sufficient subsidized housing in any form, the inadequate funding of public housing is an unlawful, retrogressive measure under international human rights law.

Public housing is a critical resource for those with low incomes, who, in the US, disproportionately consist of Black and brown people, as well as people with disabilities. Public housing is also crucially important for older adults, who are especially likely to face high rental cost burdens on the private market.

The vast majority of NYCHA residents are Black or Latinx, many of whom entered public housing following a history of displacement. The disinvestment in public housing, and failure to create adequate alternatives, threatens a crucial source of stability for these households, deepening the structural discrimination they already experience and exacerbating existing disparities.

Regardless of whether it is public or private, under international human rights law, housing needs to be adequate. As explained in the authoritative general comments of the Committee on Economic Social and Cultural Rights — the expert body charged with interpreting and monitoring state compliance with the ICESCR — this means that it should be affordable and protect occupants from cold, heat, rain, and other threats to health. Residents should have sufficient legal protection from forced evictions. Evictions should not leave a resident vulnerable to houselessness or other violations of human rights. An eviction order should only be granted if an independent authority determines that the legitimate grounds the eviction outweighs the potential consequences for the tenant.

The United States needs to urgently address the lack of adequate housing for those with low incomes. Sufficiently funding the public housing program would largely obviate the need for measures such as RAD and, with adequate oversight, can ensure that public housing residents have homes that are habitable as well as stable and affordable. To the extent RAD continues to be a major focus of housing policy in New York City, it is critical that policymakers significantly improve oversight and introduce effective mechanisms for holding PACT developers accountable and protecting the right to housing.

Recommendations

To the Federal Government

- Sufficiently fund Section 9 of the US Housing Act to enable PHAs to repair and effectively maintain their buildings.

- Do not lift the cap on the number of authorized conversions of public housing to Section 8 under the Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) until there has been a thorough, independent review of the program’s impacts on tenants, especially concerning evictions.

- Improve HUD’s oversight of PHAs by monitoring and publicly disclosing comprehensive information concerning eviction rates, housing conditions, and management responsiveness. Ensure that the process of RAD conversion respects the rights of people with disabilities.

- Allow PHAs to forgive the rental arrears of tenants in public housing, which accrued during the pandemic, and reimburse PHAs to make up for the lost revenue.

- Conduct a review of the requirement that public housing and Section 8 households pay 30 percent of their incomes in rent, to determine whether this is affordable for the lowest-income tenants and whether they must sacrifice paying for other basic needs to meet their rental obligations.

- Review the effectiveness of choice mobility vouchers and consider changes to voucher payment standards to enable residents greater ability to move to different housing if they desire.

- Ratify the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) and the Optional Protocol to the ICESCR. Enact any implementing legislation necessary to allow individuals to enforce their rights under ICESCR in domestic courts

To New York City and State Governments

- Increase funding for the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA), both to make up for federal shortfalls and to ensure that NYCHA has sufficient oversight capacity.

- Ensure that, even after the Covid-19 pandemic ends, eviction prevention relief programs no longer require a court index number of eviction filing. Ensure that all applications for rental assistance, regardless of whether a tenant has a pending eviction proceeding, are timely processed, so that an eviction filing does not become a de facto requirement.

- Review whether an extension of the eviction moratorium is warranted, based on the extent of the Covid-19 pandemic, economic conditions, and the extent to which rent relief money has been disbursed. Ensure that rent relief is sufficient to cover tenants’ arrears.

- Establish a legal framework regulating the eviction of people from their homes that incorporates a requirement for the judicial authorities to conduct an analysis of the proportionality eviction relative to its consequences for the persons evicted, and of its compatibility with the human right to housing under the International Covenant on Economic and Social and Cultural Rights, in all cases, including in cases of nonpayment of rent and in cases of occupation without legal entitlement.

To the New York City Housing Authority

- Ensure that PACT development partners have an eviction prevention plan for residents who do not sign new PACT leases.

- Extend the protections of the Fields settlement, including those preventing eviction filings being brought while an interim rent adjustment or grievance is pending, to PACT developments. Make permanent the provisions of the Fields settlement.

- Monitor whether tenants who are evicted from NYCHA or PACT housing become homeless and publicly disclose to extent to which homelessness follows eviction from NYCHA or PACT housing.

- Publicly disclose and regularly update data concerning evictions in all NYCHA and PACT developments. Such data should be comprehensive, and include all stages of the eviction process, from eviction filing to permanent eviction. Such data should also be disaggregated both by reason of eviction and by whether it occurred through housing court or through an administrative procedure.

- Publicly disclose all transactional documents underlying PACT deals.

- Encourage future PACT partners to forgive any existing arrears that tenants accrued prior to conversion, while NYCHA was managing the property, to minimize the risk of evictions that undermine rights.

- Provide residents with a private right of action to enforce the obligations of NYCHA and PACT development teams in PACT transactions.

- Extend protections of federal monitor to PACT developments or appoint another independent body to oversee work at PACT converted sites.

- Improve oversight of PACT developments and consider creating an independent oversight entity to oversee PACT sites which includes meaningful roles for resident leaders at converted developments and which provides mechanisms for PACT residents to raise concerns about their housing.

- Ensure that repairs are completed leading up to PACT conversions and accept responsibility for guaranteeing that PACT partners carry out any new needed repairs.

- Provide clear and accessible avenues for remedies to tenants, such as clear phone, online, or in-person mechanisms to file complaints or register concerns about housing issues beyond the “311” system.

Methodology

This report examines the impacts of the Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) on New York City residents of public housing owned by the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA). RAD is a federal program that has led to the greater involvement of for-profit companies in managing public housing developments.

In researching this report, Human Rights Watch reviewed data and reports from the US Census Bureau, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), NYCHA, and various housing policy organizations. These sources detail funding allocations for various housing programs, demographic information on public housing residents, eviction rates, and the impacts of funding reductions on living standards.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 40 people for this report, between January and June 2021, including 17 residents across five NYCHA housing developments that had recently undergone RAD conversions. Human Rights Watch also interviewed 10 current and former residents across nine different non-RAD NYCHA housing developments, one of whom was also interviewed for her expertise as a lawyer working on housing. Most residents we spoke with were women of color. Over 90 percent of NYCHA residents are Black or Latinx, and over 75 percent of NYCHA households are headed by women.[1]

In addition, Human Rights Watch interviewed 15 housing policy specialists, lawyers, and activists, as well as one private developer managing a NYCHA development.

Most interviews were conducted by videoconferencing. Some interviews were conducted in person. Research for this report was conducted during the Covid-19 pandemic, with staff taking precautions to minimize the risk of transmission. Most in-person interviews were kept brief and narrowly focused, to minimize exposure.

All interviewees freely consented to the interviews. Human Rights Watch explained to them the purpose of the interview and did not offer any remuneration.

Human Rights Watch spoke with Greg Russ, Chairman and CEO of NYCHA and Johnathan Gouveia, NYCHA’s Executive Vice President of Real Estate Development, and Vicki Been, Deputy Mayor for Housing and Economic Development for New York City. We also wrote letters to the companies which develop and manage various PACT developments across New York City, outlining concerns and providing an opportunity to respond.

I. Background

The US Congress has subjected public housing — housing that is owned and typically operated by a city or county government agency called a public housing authority (PHA) —to devastating funding cuts over the last two decades.

Because public housing serves a low-income population and rents in public housing are capped at 30 percent of household income, rental income alone is insufficient to finance ongoing maintenance and major repairs. PHAs thus rely on subsidies. The primary sources of funding for PHAs are two congressionally authorized funds: the capital fund, used for large repairs, and the operating fund, used for routine maintenance and operations.[2] Both have been drastically cut since 2000, risking the rights to adequate housing of the around 2 million people living in the over 950,000 public housing apartments nationwide.[3]

In 2021, the overall budget of the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) was $69.3 billion, of which $2.9 billion was allocated to the public housing capital fund.[4] Adjusted for inflation, this amount is around 35 percent lower than the capital funding allocation in 2000, which in 2021 dollars would be worth $4.5 billion. These cuts to the capital fund did not begin in 2021 but have largely persisted since 2000.[5]

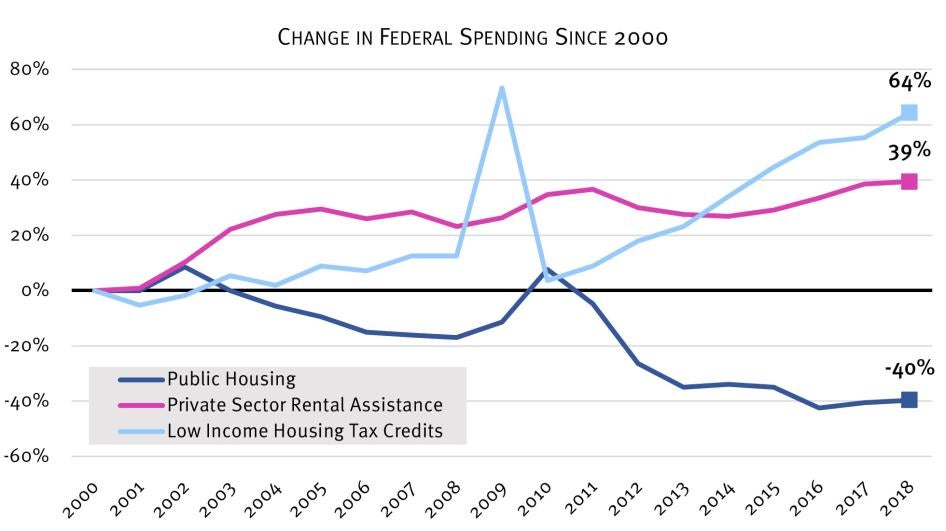

These cuts reflected a turn away from public housing in favor of programs which subsidize the private sector, a turn encapsulated by the 1998 Quality Housing and Work Responsibility Act (QHWRA). The QHWRA proclaimed that the policy of the US is that the “Federal Government cannot through its direct action alone provide for the housing of every American citizen, or even a majority of its citizens.” Rather, the role of government would be to “promote and protect the independent and collective actions of private citizens to develop housing.”

The QHWRA made it easier for PHAs to demolish public housing by allowing PHAs to use capital funding to tear down their developments and by formally repealing the requirement that for each unit demolished a new unit must be built.[6] The act also contained the Faircloth Amendment, which barred PHAs from using federal funds to construct new public housing if it would result in the PHA having more public housing units than it did in October 1999.[7] While the Faircloth Amendment did not itself cut funding, it gave formal legal expression to the federal government’s abandonment of public housing. “The Faircloth Amendment is the Magna Carta of federal disinvestment,” Victor Bach, Senior Housing Policy Analyst at the Community Service Society in New York City, a nonprofit organization advocating for policies that benefit those with low incomes, explained to Human Rights Watch. “It really shows Congress’ attitude toward public housing . . . the idea was to reduce the number of public housing units nationwide.”[8]

Faced with few resources to fix or upgrade apartments or crucial building systems such as plumbing, heating, and elevators, the deterioration of the public housing stock has spiraled out of control. Nationally, between 8,000 and 15,000 public housing apartments have been closed or demolished each year because they are no longer habitable.[9] The number of public housing apartments peaked in 1994 at around 1.4 million and fell to around 1.3 million by 2000.[10] Since then, this number has fallen by around 310,000,[11] but years of deferred maintenance — where major repairs are postponed — have increased the cost to repair the over 950,000 homes that remain. According to the National Association of Housing and Redevelopment Officials, at least $70 billion is now required to meet the accumulated repair needs of the public housing stock and ensure safe, habitable homes for residents.[12]

Congress has also consistently failed to adequately fund the public housing operating fund, which finances daily operations and maintenance. HUD determines each PHA’s operating subsidy using a formula, which identifies the amount of operating support each PHA needs to cover the gap between its rental income and operating costs.[13] However, between 2000 and 2019, in only 3 years (2002, 2010, and 2011) did Congress provide sufficient funding to allow HUD to provide PHAs the full amount for which they were eligible under HUD’s formula and which was necessary to cover this gap.[14] In absolute terms, the operating fund has been increased in recent years. Congress allocated $4.8 billion to the operating fund in 2021, about equal, when adjusted for inflation, to what Congress allocated in 2000. [15] Even this amount, though, is around 4 percent less than what PHAs need under HUD’s formula,[16] and fails to make up for the cumulative losses caused by repeatedly inadequate appropriations.

Funding for public housing, historically, has been almost exclusively provided by the federal government.[17] In some cases, states and localities have provided additional funding for repairing and operating public housing,[18] though these have not made up for the cuts in federal funding to PHAs, as capital needs continue to grow.[19]

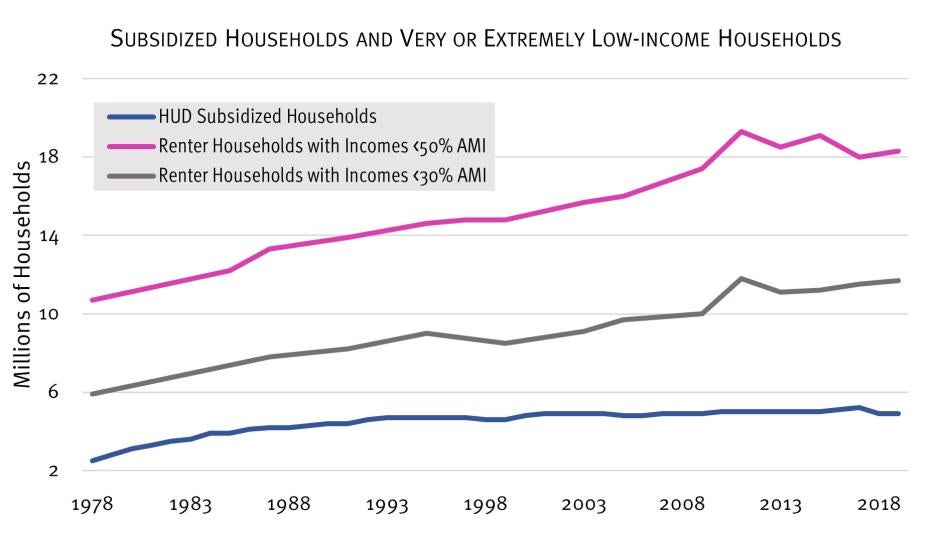

These cuts have occurred despite the immense need for housing assistance for low-income people. The number of extremely or very low-income households — those with incomes below 50 percent of their metropolitan area’s median income — stands today at nearly 18 million, around 3 million more than in 1999.[20] Nearly 80 percent of such households are cost-burdened, spending more than 30 percent of their income on rent and utilities.[21]

The Effects of Funding Cuts on NYCHA

The federal and state cuts devastated the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA), which, like other PHAs, receives most of its public housing funding from the federal government and relies on such subsidies to cover the gap between resident rents – which are capped at 30 percent of household income – and their operating and maintenance costs.

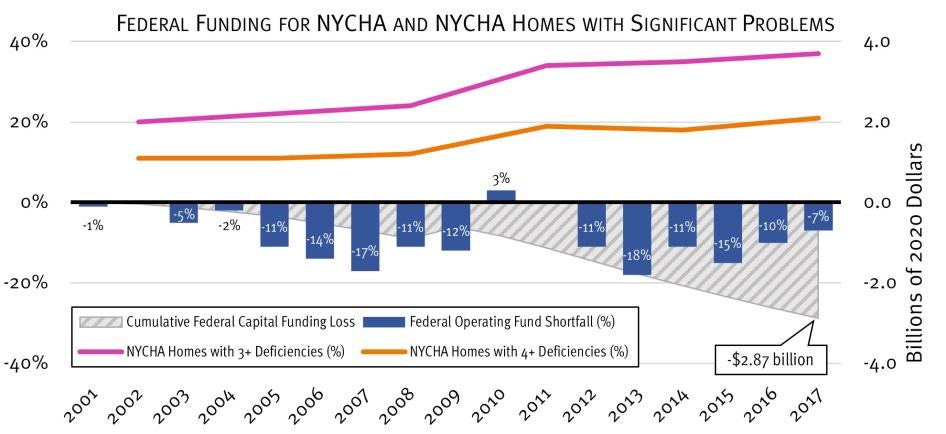

Had federal capital funding remained at 2001 levels ($619 million in 2020 dollars), NYCHA would have had an inflation-adjusted cumulative total of $2.87 billion in additional capital funding between 2001 and 2017.[22] Like other PHAs, NYCHA has faced consistent federal operating funding shortfalls since 2000, where the operating subsidy NYCHA received was less than they were eligible for under HUD’s formula and insufficient to cover the costs of basic operations. These shortfalls forced NYCHA to run deficits, reduce staffing, and forgo necessary maintenance.[23]

New York City funding for public housing has been stagnant, whereas state funding has dropped precipitously. Between 2002 and 2017, the city government’s capital support for NYCHA’s public housing totaled around $586 million, a small fraction of the amount the city spent on private-sector affordable housing initiatives often aimed at those with higher-incomes than public housing residents.[24] In addition, unlike most other PHAs, some of NYCHA’s public housing was constructed using state funds, and as such, it was ineligible for federal support under Section 9 and relied on ongoing support from the state. However, in 1998, at the urging of then-Governor George Pataki, the state government terminated operating support for the units constructed using state funds. This lack of state support forced NYCHA to use its already stretched federal resources to maintain now-unfunded state units.[25] In addition, New York state provided no capital funding between 2002 and 2014 for either state-built developments or for NYCHA housing that was built under the federal Section 9 program.[26]

As a result of consistently inadequate funding, NYCHA has been unable to make needed repairs and upgrades to its aging housing stock and basic operations have been imperiled. Multiple NYCHA residents told Human Rights Watch that their living conditions have steadily deteriorated over the last two decades. They described being forced to endure unsafe conditions, including leaks, harmful mold, infestations, failing heat, and peeling lead paint.[27] Often, they wait weeks or even years for repairs.

As the chart below illustrates, like other PHAs over the last two decades, NYCHA has consistently faced federal operating fund shortfalls and declining federal capital support. These cuts coincided with an increase in NYCHA households reporting major deficiencies such as water leaks, failing heat, peeling paint, and the presence of rodents. Between 2005 and 2017, NYCHA homes went from having comparable or lower deficiency rates than private-sector low-income housing to having rates over twice as high.[28] “Public housing that worked became public housing that was dysfunctional,” Bach told Human Rights Watch. [29]

Greg Russ, Chair and CEO of NYCHA, provided Human Rights Watch an example of how the lack of capital funding has forced the authority to defer needed upgrades, which in turn drives up the cost of routine maintenance. “In a unit that has been well-maintained — which includes capital — I can send a mechanic to fix a leak,” Russ said. However, to fix a leak in a NYCHA building, multiple workers from different trades are needed, leading to higher costs and longer delays. Moreover, lacking the money to replace major building systems, NCYHA must have parts specially manufactured since the systems are so old the parts for it are no longer produced. “For NYCHA, the lack of capital is not only increasing the deterioration of buildings,” Russ said. “It is driving the cost of everything up, so that it’s also impacting the operating budget in a negative way.” [30]

As part of an agreement, discussed below, following a lawsuit between the federal government and NYCHA concerning deteriorating conditions, New York City has committed to providing $2.2 billion in funding for NYCHA between 2019 and 2028.[31] This is a substantial increase from previous funding levels, which totaled just $462 million over the previous ten years.[32] The state has also committed $450 million in funding since 2019.[33] Yet given decades of deferred maintenance, much more funding is now needed to halt the decline in living conditions caused by the worsening state of its housing. NYCHA estimates that over $40 billion is required to fully address the repair needs of its public housing, and this figure could grow to nearly $70 billion by 2028.[34] Unless sufficient funding is found, there is a significant risk that NYCHA’s buildings will continue to deteriorate, and many of its residents will continue to live in conditions that NYCHA has recognized are uninhabitable.

Public Housing: A Refuge of Affordability

In public housing, tenant rents are capped at 30 percent of household income. As such, in a city with a high cost of living,[35] NYCHA is a refuge for the lowest income residents of New York, who are finding ever fewer alternative housing options they can afford. While it only comprises 9 percent of New York City’s occupied rental housing stock, NYCHA housing accounts for 57 percent of the units affordable to those with incomes below 30 percent of the area median, and 29 percent of homes affordable to those with incomes at or below 50 percent or less of the area median.[36] According to New York University’s Furman Center, measured in constant 2017 dollars, NYCHA public housing accounts for 64 percent of all homes in New York City with monthly rents under $500, up from 36 percent in 2002.[37]

Officially, over 350,000 people live in NYCHA’s public housing.[38] However, the true number could be upwards of 550,000, as many NYCHA households have “off-lease” members who have not been authorized to live in a NYCHA apartment.[39] The affordability of public housing makes it a critical lifeline for low-income households across New York City. Most NYCHA residents between the ages of 18 and 61 are employed, but their median household income is just $18,473, compared to $61,297 in all other types of housing in the city.[40] Around 92 percent of NYCHA residents are Black or Latinx , and as many as 34 percent have a disability.[41]

Kristen Hackett, an activist with the Justice for All Coalition and PhD student researching public housing at the City University of New York, told Human Rights Watch that many residents “found themselves living in public housing after a series of displacements, both within the context of their own lives and intergenerationally.”[42]

Jasmin Sanchez’s story is a testament to this history. Sanchez was raised by her grandparents, who came to New York City from Puerto Rico in 1959. Her grandparents rented an apartment on the Lower East Side, which was demolished as part of an urban renewal project. Her grandparents were then forced to move to another apartment on the Lower East Side, but, according to Sanchez, in the early 1970s, were again displaced after their landlord burned down the apartment building. Such arson was a common occurrence at the time, as landlords abandoned buildings in predominately Black and brown neighborhoods following disinvestment and neglect.[43] After being displaced a second time, Sanchez’s family was able to move into public housing, where they could raise a family. “They found permanent housing in public housing, after being hit so hard with horrific housing circumstances due to our government,” she says. “They no longer had to worry about not having a place to live.” [44]

Housing and Structural RacismThere are entrenched racial disparities in US housing, reflecting the structural racism perpetuated and promoted by US government agencies and policies. The practice of “redlining” — in which private lenders and the federal government denied mortgage financing to those in predominately Black or immigrant neighborhoods — systemically denied Black and brown people access to homeownership. Moreover, the Federal Housing Administration, which was established to reform mortgage practices and provide mortgage insurances by private lenders, implemented its own permanent systems to preserve and intensify racial segregation.[45] As of 2021, 45 percent of Black households owned homes, compared to 74 percent of white households.[46] Black homeowners are also almost five times more likely to own homes in formerly redlined areas than in formerly “greenlined” areas, which were deemed to be lowest risk for mortgage lenders. These disparities are major components of persistent racial wealth gaps, given that homeownership is crucial to wealth-building in the US.[47] Beyond homeownership, there are also racial disparities in the habitability and stability of housing. Black and brown households are far more likely to be rent burdened, evicted, or live in overcrowded or substandard homes.[48] The history of public housing cannot be separated from this history of structural discrimination. Many public housing developments were originally constructed as part of “slum clearance” programs that displaced thousands of Black, brown, and low-income households.[49] Because public housing was often segregated, in some cases, these programs had the effect of turning formerly integrated communities into segregated ones.[50] In the mid-twentieth century, pressure from private real estate interests helped place strict income limits on public housing, displacing higher-income tenants.[51] Combined with “white flight” — driven by racist attitudes and subsidized by federal policies enabling low-cost home ownership for white families [52] — these changes exacerbated the segregation of public housing and, because rental income dropped, made PHAs more reliant on federal subsidies.[53] Today, public housing is a critical resource for Black, Indigenous, and other people of color throughout the US. In New York City, public housing has preserved affordable rental housing opportunities for Black and brown residents. [54] However, without further structural reforms, public housing cannot itself solve a housing crisis that is influenced by racialized and classist policy choices and which perpetuates segregated housing and the Black-white wealth gap.[55] Given its importance as a source of affordable housing for marginalized communities, disinvestment from public housing perpetuates racial disparities in both housing quality and stability. Moreover, beyond the fact that Black, Indigenous or other people of color disproportionately reside in public housing, Black and brown public housing residents have borne the brunt of recent waves of demolition. According to a 2011 study, PHAs across the country “systematically” chose to demolish public housing developments that had disproportionately high Black occupancy compared with other public housing in their cities.[56] In addition to the trauma inherent in such displacement, those forced to relocate following demolition often faced increased housing costs and limited improvements in income or employment.[57] |

The Rental Assistance Demonstration Program (RAD)

The Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) is a program developed by HUD in response to inconsistent and meagre federal appropriations to the public housing capital and operating funds. Authorized by Congress in 2012, RAD is designed to help PHAs finance large renovations, as well as fund ongoing maintenance and property management.

RAD does not allocate money to the conventional public housing program, which was funded by annual grants under Section 9 of the US Housing Act and by annual congressional appropriations.[58] Rather, it allows PHAs to fund their developments using long-term contracts governed by Section 8, a program typically used to subsidize private sector housing. In addition, RAD allows PHAs to take advantage of other funding sources, such as federal tax credits, which are also primarily used to finance private low-income housing. In practice, RAD often entails PHAs entering into various types of public-private partnerships, with for-profit entities sometimes assuming responsibility for management, including making repairs, collecting rent, and initiating eviction proceedings.

As the data below shows, although long-term contracts under Section 8 are also subject to annual appropriations,[59] congressional funding has favored subsidizing private sector housing programs rather than funding public housing. Given this, for many PHAs, the choice is between RAD or possible demolition.

NYCHA utilizes RAD through a program called “Permanent Affordability Commitment Together,” or PACT. Under PACT, public housing developments are leased to private developers, and private companies take over building management. NYCHA plans to convert one-third of its apartments, or 62,000 homes, over 10 years using PACT. The first NYCHA building converted in 2016, and as of March 2021, around 9,500 homes are under the program.[60] Residents and advocates are sharply divided over NYCHA’s strategy.[61]

Given the large number of units in NYCHA’s portfolio and its importance as a key source of affordable housing in New York City, it is crucial that any changes to these units’ management protect the affordability of housing and security of tenure while management protect the affordability of housing and security of tenure while simultaneously improving conditions and ensuring accessibility for people with disabilities.

RAD also impacts public housing residents across the US. Congress has greatly expanded the program, increasing the total number of eligible homes from 60,000 in 2012 to 455,000 in 2018.[62] Based on a Human Rights Watch analysis, given that, on average, 2.1 people live in each public housing apartment, over 950,000 people could be impacted. [63] Including off-lease tenants, the true number could be far higher.

Citing concerns over oversight, various advocacy organizations have called for Congress to not raise the cap on conversion. The National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC) has called for detailed assessments of the impact of RAD on tenants, recommending that the cap on RAD conversions to remain at current levels “until this ‘demonstration’ has convincingly shown that HUD will rigorously monitor PHA and owner compliance with all tenant protections.”[64]

In response to criticism from the Government Accountability Office (GAO), HUD has developed, or is in the process of developing, mechanisms for monitoring various aspects of the PACT program to ensure compliance with various tenant protections.[65] In September 2021, HUD announced a complaint mechanism to enable residents of RAD-converted developments, as well as advocates, to raise their concerns with HUD.[66] However, HUD does not track evictions across RAD properties, nor across any other subsidy program, including conventional public housing, and non-RAD Section 8 housing.[67] The “We Need Eviction Data Now Act,” introduced in September 2021 in the US Congress, would require HUD to establish and maintain a national database of evictions, which would include data for HUD-assisted households, including conventional public housing and RAD-converted housing.[68] HUD did not respond in writing to Human Rights Watch questions about the RAD program.

A Tale of Unaffordable Housing

RAD is a continuation of a trend starting in the mid-1970s with the creation of the Section 8 program, and accelerating since 2000, in which Congress has favored private sector-led programs over direct support for public housing in the US.[69] This prioritization of the private sector is happening in the context of insufficient overall support for all subsidized housing programs. Throughout the US, there are just 37 affordable and available homes for every 100 renter households with incomes below 30 percent of their metropolitan area’s median income (AMI) and just 60 homes for every 100 households with incomes below 50 percent AMI.[70] Yet while overall budget authority — how much HUD is authorized to spend — for all HUD programs combined has increased since 2000, Congress appropriates far less to these programs today than it did 40 years ago. HUD’s 2021 budget of $69.3 billion, which is among this highest in the last 20 years, pales in comparison to the compared to $159 billion (in 2021 dollars) Congress appropriated for HUD in 1978.[71]

Because of these insufficient appropriations, HUD’s actual expenditures are increasingly used to renew existing subsidy contracts rather than add new affordable homes.[72] Combined with the increase in the number of extremely or very low-income households, this has resulted in a growing gap between the number of low-income households and the number of HUD subsidized homes.

II. What is RAD?

RAD, at its most basic, allows PHAs to change how their public housing developments are financed. The program allows PHAs to “convert” their developments from the conventional public housing program under Section 9 of the US Housing Act, to a long-term contract under Section 8 of the Act,[73] a program typically used to subsidize private low-income housing. Doing so allows PHAs to access a funding source that has enjoyed more generous and stable congressional appropriations. Combined with the increased regulatory flexibility of the Section 8 program, this more stable funding allows PHAs to better access financing on the private market as well as utilize other housing subsidies typically used by the private sector, such as tax credits, which are sold to outside investors in exchange for equity to finance construction or renovation.[74] Like Section 8 itself, tax-credit spending has grown while spending on public housing has declined.[75]

On paper, the additional resources should help PHAs ensure habitable housing, while provisions in the legislation and regulations governing RAD should ensure that tenants remain protected. In practice, those goals have not always been met, and existing rules governing both RAD and traditional public housing provide those managing housing with significant discretion which can impact tenants.

By utilizing the Section 8 program, RAD allows PHAs to access both private financing, but also substantial public subsidies that, before, were largely reserved for private sector. In doing so, the program, opened the door to significant private sector involvement in the operations, financing, and sometimes the ownership of public housing.

However, it is difficult to make generalizations about the RAD program nationally, as the extent and form of private-sector involvement varies by public housing authority. Various PHAs have transferred ownership and operation of their developments to private, for-profit entities.[76] When a PHA sells public housing to a for-profit private entity — which often occurs in transactions utilizing federal tax-credits — the RAD authorizing statute and subsequent HUD notices require either the PHA itself, another public entity, or a nonprofit to retain an interest in the property by, for instance, utilizing a ground lease or retaining certain control rights over the private entity, as approved by HUD.[77]

Other PHAs, however, have limited the for-profit sector’s involvement in the operation of their RAD properties. For example, various PHAs partnered with nonprofits or created single-purpose subsidiaries to assume ownership of converted homes,[78] and of 20 PHAs surveyed in an evaluation of RAD prepared for HUD, 15 still managed their RAD developments.[79] Many other PHAs utilized no private funding whatsoever, and simply converted to RAD to take advantage of more stable annual appropriations.[80]

PACT: Public Money to Private Hands?

NYCHA has chosen to almost exclusively privatize the administration of public housing while retaining ownership. The authority typically partners with for-profit developers and utilizes private property managers. Under PACT, NYCHA retains ownership of the land and buildings but leases them to one or more private developers for 99 years. Private management companies manage PACT-converted NYCHA buildings, collect rent, and initiate evictions. NYCHA retains an oversight role, maintaining the waiting lists for PACT developments and monitoring evictions, tenant selection, and repairs.[81] NYCHA’s most recent request for expressions of interest (RFEI), which calls for companies to bid on a PACT contract, requires future PACT development teams to include at least one minority-or-woman-owned or nonprofit developer to help build the capacity of, and increase opportunities for, such developers.[82]

As of March 2021, nearly 22,000 residents across 50 formerly NYCHA-managed developments have seen their homes converted from NYCHA management to PACT.[83] NYCHA has partnered with 26 different developers and 11 property management companies to implement the program.[84] The authority has partnered with for-profit developers in every case but two and utilizes private property managers.[85]

New York City officials gave a variety of reasons for choosing to work with for-profit interests. Greg Russ, Chair and CEO of NYCHA, told Human Rights Watch that nonprofit developers often lack sufficient capital to participate in PACT conversions.[86] Johnathan Gouveia, NYCHA’s Executive Vice President for Real Estate Development, and Vicki Been, Deputy Mayor for Housing and Economic Development for New York City, told Human Rights Watch that PACT developers have experience developing affordable housing, and that NYCHA is utilizing private property management because of the large size of NYCHA’s portfolio coupled with its dwindling resources. “We’re trying to get to a place where we’re rationalizing and right-sizing NYCHA, trying to get to a place where we can better serve our residents,” Gouveia said.[87] Been also stated that the competition among private managers creates a “laboratory of experiment,” from which NYCHA could learn to operate more efficiently.[88]

This approach gives profit-driven entities unprecedented control over public housing residents, who are among the city’s most vulnerable. At time of writing, the program has financed over $1 billion in repairs and is eventually intended to address nearly $13 billion in capital needs.[89]

PACT deals are designed to be profitable for the private sector to incentivize their participation and like other RAD deals, require significant public money. Typical sources of revenue consist of tenant rents, a developer fee, as well the federal subsidy dollars attached to Section 8 contracts and other federal subsidy programs that NYCHA has utilized to make RAD transactions financially feasible. One of the primary sources of debt financing for these projects are tax-exempt bonds, issued by New York City’s municipal housing finance agency, the New York City Housing Development Corporation (HDC).[90] According to NYCHA’s May 2021 RFEI, it requires development partners to contribute 5 or 10 percent of the total development cost minus existing debt, developer fee, and reserves, depending on whether city subsidies are involved.[91] For the PACT Conversions in the May 2021 RFEI, total development costs range between $247 and $380 million.[92]

However, each transaction is different, and NYCHA does not appear to publicly disclose the financing mix for each transaction. For instance, Johnathan Cruz, Development Project Manager at MDG Design and Construction, a developer for three PACT projects, told Human Rights Watch that the PACT conversion of Betances Houses in the Bronx used long-term Section 8 contracts to secure a mortgage on the development from a private bank, rather than use HDC bonds. Cruz added that the Betances PACT developers contributed 15 percent of the project’s costs.[93]

PACT differs in some respects from other PHAs’ models for RAD conversions, but its use of public money is typical. An evaluation of RAD prepared for HUD found that, through October 2018, the program had raised $12.6 billion in total funding.[94] However, the vast majority of this amount was public money. Proponents of RAD argue that the program uses public dollars to attract high amounts of private investment, and HUD had previously touted leverage ratios (i.e., how many dollars of external financing is raised for each dollar of RAD subsidy) as high as 19:1. However, their methodology was criticized by GAO for erroneously considering certain types of public funding as private.[95] A final evaluation report on RAD prepared for HUD, incorporating the GAO’s criticisms, found that for every $1 of publicly held or subsidized funding, just $0.29 of private, unsubsidized financing was raised.

Because RAD is formally budget neutral and does not provide any additional housing subsidy dollars, utilizing other public resources for the program comes at the cost of using them to create or preserve additional affordable housing. A 2021 study, published in Cityscape, a scholarly journal published by HUD’s Office of Policy Development and Research, found that RAD’s use of low-income housing tax credits (LIHTCs) constrains the LIHTC program’s “capacity to expand the supply of affordable rental housing and preserve existing affordable housing outside of the public housing program.” [96] That same paper noted that funding the public housing capital fund would be the “[i]n many ways . . . the simplest and most direct way of preserving the nation’s public housing” [97]

III: Insufficient Oversight and Loss of Key Protections

Compared to NYCHA’s conventional public housing, where NYCHA is essentially the only entity involved in the operation and maintenance, PACT housing involves a number of private entities, in addition to NYCHA. Consequently, some protections resulting from lawsuits against NYCHA no longer apply to PACT developments.

“The conversion of public housing to project-based Section 8 under PACT/RAD fundamentally changes who is responsible for ensuring the many, interrelated rights of tenants,” Elizabeth Gyori, a staff attorney at Legal Services New York City (LSNYC) who has represented PACT tenants seeking repairs, told Human Rights Watch. “Prior to conversion, the public housing authority was ultimately responsible for safeguarding tenants' rights. Under PACT/RAD, responsibility for protecting key rights--such as the right to safe and habitable apartments, the right to income-based rents and due process rights--is spread out among multiple actors, including the private landlord, the management company, NYCHA and HUD.”[98]

Federal Monitor Agreement

In 2018, the US Attorney for the Southern District of New York (SDNY) sued NYCHA, alleging that, since at least 2010, the authority had systematically misled HUD inspectors, underreporting a variety of critical issues, including lead paint, widespread harmful mold growth, pest infestations, lack of heat, and failing elevators.[99] According to the complaint, NYCHA failed to remediate widespread mold growth, and although NYCHA knew about the risks of lead poisoning, it failed to carry out required visual inspections.[100] The suit also alleged that NYCHA developed protocols to hide such issues from HUD inspectors, including distributing a “Quick Fix Tips” guide, which directed staff on how to superficially cover up issues in buildings. It also alleged that workers were not trained in lead-safe work practices, and NYCHA manipulated the work order process to make it appear, falsely, that it was reducing its maintenance backlog.[101]

As a result of the lawsuit, NYCHA and the SDNY entered into an agreement appointing a federal monitor to oversee the agency to ensure its compliance with federal law.[102] As part of this agreement, NYCHA admitted to having unsafe conditions in its housing concerning mold, lead, heating, elevators, and pests, as well as to making untrue statements to HUD regarding these conditions, manipulating its work order process, failing to conduct visual lead paint inspections, failing to ensure that staff are trained in lead-safe work practices, and distributing the “Quick Fix Tips” guide.[103]

The federal monitor agreement has compliance requirements and standards as well as reporting requirements regarding these issues in NYCHA buildings.[104] In particular, the agreement lays out detailed protocols for the removal of lead-based paint, and standards for heat, mold, pests, and elevators.[105] The monitor has full access to NYCHA’s data systems and documents, and, in the event of noncompliance by NYCHA, can issue remedial directives which are enforceable if approved by HUD and the SDNY.[106]

However, while some provisions of this agreement apply to PACT-converted properties, most do not. NYCHA must ensure that lead abatement in converted properties is carried out in accordance with federal regulations, but other portions of the agreement concerning pests do not apply to PACT buildings.[107] PACT properties also appear exempt from detailed reporting and performance obligations concerning elevators and heating. The agreement merely specifies that NYCHA “will transfer” 150 elevators and 200 boilers, which are used for heating, to third-party management through PACT, and that developers “will replace elevators as needed” and “replace or repair the boiler and accessory heating systems as needed.”[108]

Fields Settlement

In 2019, twelve public housing residents sued NYCHA under Section 9 of the US Housing Act, alleging that NYCHA had a pattern and practice of failing to quickly and accurately determine residents’ incomes, resulting in illegal rent overcharges, since rent in public housing is based on a household’s adjusted income.[109] The residents further alleged that these overcharges resulted in improper eviction proceedings being brought against them.[110] NYCHA disputed the residents’ allegations, stating that its income review procedures are consistent with federal law.[111]

In July 2021, a federal court approved a settlement agreement between NYCHA and the residents. While NYCHA did not admit wrongdoing, the settlement contains several protections, which will apply starting in January 2022 and last for three years, for residents who believe they are being overcharged. Firstly, NYCHA cannot commence an eviction proceeding while an interim income recertification — in which a resident requests that NYCHA adjust its rent calculation due to a loss in income — is pending.[112] Secondly, NYCHA cannot start an eviction proceeding while a resident has an open grievance concerning NYCHA’s rent calculation.[113] If NYCHA improperly commences an eviction, NYCHA must seek to discontinue the eviction proceeding until the correct rent amount is determined and credits are issued for any past overcharges.[114]

The Fields settlement agreement does not apply to PACT buildings, which are governed by Section 8 of the US Housing Act.[115] Under PACT, NYCHA still determines, based on household income, how much a resident must pay in rent. For public housing residents, income determinations are made by NYCHA’s public housing department, whereas income determinations for PACT residents are made by NYCHA’s leased housing department, which also administers NYCHA’s Section 8 tenant voucher program.[116] This means that if NYCHA commits an error in calculating a PACT resident’s rent, and the PACT developer commences an eviction proceeding, the resident will not have the protection that Fields offers to NYCHA residents: freezing eviction proceedings while the rent calculation grievance is resolved.

Multiple PACT residents told Human Rights Watch that they believed that NYCHA erred in calculating their rent, though Human Rights Watch was unable to verify the validity of these claims. However, one resident, Dianna R., saw her rent increase from 30 percent of her income — the amount at which rent in both public housing and PACT is capped — to over 50 percent.[117] After she first found it difficult to either obtain an explanation for the increase or have it reduced, NYCHA lowered her rent.[118] An eviction proceeding was not commenced against Dianna, though such a proceeding would have likely been barred by the eviction moratorium in place at the time due to the Covid-19 pandemic. As discussed below, even if an individual does not ultimately lose their home, even merely commencing an eviction proceeding can have severe consequences on a tenant’s ability to secure housing in the future.[119]

NYCHA Has Disclaimed Responsibility for Repairs

Residents’ legal recourse is also insufficient. Tenants can sue over housing conditions based on New York landlord-tenant law and concerning landlord obligations in their leases. PACT leases contain requirements that tenants have access to a grievance process before they can be evicted and specifies what constitutes “good cause” for an eviction.[120]

Additional protections for residents, over and above standard landlord-tenant law, are contained in the contracts between NYCHA and private companies that form the basis of PACT deals. However, only HUD and NYCHA, not residents themselves, have the ability to enforce them.

Under a PACT subsidy contract obtained by NY Commons, a collaboration of nonprofit organizations that catalogs information about publicly owned land in New York City, as well as a template control agreement available on NYCHA’s website, developers and managers must maintain the buildings and make ordinary and extraordinary repairs. PACT developers must also meet HUD’s federal “Housing Quality Standards,” minimum standards that all Section 8 housing is required to meet. [121] PACT development teams must report information to NYCHA regarding repair times and apartment conditions, and NYCHA can select a new property manager if the existing one is failing to meet its obligations. Finally, these transactional documents require PACT teams to respect various tenant rights under the RAD statute and HUD notices.[122]

However, because PACT transactional documents explicitly disclaim third-party beneficiary rights, there is no private right of action for tenants to enforce these contractual provisions. Only NYCHA and HUD can enforce them.[123]

Moreover, Gyori, who has represented PACT tenants seeking repairs, told Human Rights Watch that, when sued, NYCHA has disclaimed responsibility for ensuring repairs, arguing that “they cannot be held responsible because if they were to do repairs on the premises, they would be trespassers and would be arrested.”[124] “That’s the whole point of doing PACT, is that NYCHA is no longer the day-to-day manager,” Lucy Newman, a staff attorney at the New York City Legal Aid Society, told Human Rights Watch. “It’s to get [buildings] off of [NYCHA’s] books.”[125]

Gyori also pointed out that NYCHA has not publicly disclosed all of the transactional documents that underlie PACT deals, which she says can make it more difficult to challenge the actions of NYCHA and PACT developers.[126]

In a response to a letter from Human Rights Watch, NYCHA stated that “it is a fundamental component of the PACT program to bring in another entity, the PACT Partner, to be responsible for rehabilitation and repairs in lieu of NYCHA.” They added that NYCHA requires regular reporting from PACT partners on maintenance and repairs and “can ultimately replace a PACT Partner if they are not performing to NYCHA’s expected standards and/or as required by federal, state, or local codes.” [127]

Given these issues, many residents feel as though NYCHA is not effectively monitoring PACT conversions. “We were supposed to have an overseer,” Jeanine Henderson said. “You don’t have anybody really, really watching.”[128] Justin Cuevas stated that there needs to be a “sizeable meeting between NYCHA, tenants, and incoming management,” where NYCHA can make clear its expectations and tenants can express their concerns.[129]

“I don’t know that there is any particular entity at NYCHA that is overseeing post-conversion issues,” Victor Bach, Senior Housing Policy Analyst at the Community Service Society in New York City, told Human Rights Watch. “There clearly needs to be a specifically designated oversight entity that monitors [PACT] conversions.”[130] The Community Service Society has called for the creation of an oversight entity, independent of NYCHA and PACT developers, to actively monitor any issues following conversion and which includes seats for resident leaders from converted developments to “channel and address emerging resident concerns.”[131]

IV. Evictions and Renter Protection Fears under PACT

On paper, both RAD itself and PACT guarantee residents largely the same procedural protections against eviction that they have under traditional public housing governed by Section 9 of the Housing Act.[132] These provide that eviction may not be arbitrary and may only take place for non-payment of rent, other serious or repeated violations of lease terms, or other good cause.[133] Before an eviction can be initiated, residents are entitled to an informal grievance procedure, in which they are notified of the grounds for eviction and informed of the evidence against them. Residents are then given the opportunity to present contrary evidence or question witnesses before an impartial hearing officer or staff member.[134]

However, a key factor in protecting tenants’ right to housing is NYCHA’s exercise of its wide discretion over decisions affecting residents’ ability to stay in their homes. [135] For example, NYCHA staff are empowered to develop payment plans to resolve rent arrears and consider mitigating factors when tenants face possible eviction for criminal activity, which includes both violent crimes as well as drug and property offenses.[136]

The precarity of many tenants can make late payments unavoidable. Although rent for both public housing and PACT residents is capped at 30 percent of income, many tenants still struggle to afford it. In the latest Mayor’s Management Report, NYCHA reported that around 40 percent of its households — over 65,000 families — are currently in arrears.[137] This issue predates the Covid-19 pandemic, as from 2016 through 2019, the percentage of households with arrears increased from 28 percent to 35 percent.[138] Consequently, many tenants likely face homelessness if they are evicted.

NYCHA can initiate non-payment proceedings with only 14 days’ notice under its leases, but multiple residents, as well as Sylvia T., a former NYCHA housing assistant, told Human Rights Watch that NYCHA only starts eviction proceedings after a tenant is at least 2.5 months in arrears.[139] Several residents told Human Rights Watch that NYCHA’s leniency depends on the discretion of individual staff, but many reported instances when NYCHA was flexible concerning rent.[140]

Many residents in both NYCHA-managed housing and privately managed housing under PACT are concerned that private entities will be more likely to evict residents.[141] Some residents Human Rights Watch spoke with specifically mentioned the example of Ocean Bay, discussed in detail below, which experienced an increase in evictions following its conversion in 2017. Due to the eviction moratorium put in place in March 2020 in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, which remained in effect until January 15, 2022, it is difficult to evaluate whether more recent PACT conversions have been associated with increased eviction rates.

“The tenant never wins, only landlords,” Jackie Lara, who lives at a NYCHA development slated for PACT conversion, told Human Rights Watch. “Because it’s about money. Everything is money.”[142] Cesar Yoc, a resident in NYCHA-managed housing in the Bronx, expressed a similar concern. “That’s what the fight is, to protect us from investors who don’t give an ‘F’ about us,” he told Human Rights Watch.[143] NYCHA appears to be aware of this potential tension between resident stability and the need of its private partners to make returns on their investments. Gregory Russ, NYCHA’s chair and chief executive officer, told Human Rights Watch that NYCHA “recognized the issue about potentially having a private developer,” adding, “I want to keep the resident protections because I don’t want that model to overwhelm the residents somehow.”[144] NYCHA’s plan to rehabilitate the two-thirds of its stock not currently slated for PACT involves transferring its developments to a newly created public agency.[145]

The Eviction ProcessEach step in the eviction process can have serious consequences for tenants. Formal evictions typically begin with a court filing.[146] Because eviction filings are public court records, they can appear on tenant screening reports utilized by landlords. Even if tenants ultimately remain in their homes, the filing itself may negatively affect their ability to find housing in the future.[147] If a court rules in favor of the landlord, they receive an eviction judgment, which enables the landlord to remove a tenant from their home. Having an eviction judgment also negatively affects a resident’s ability to find future housing and will likely impact one’s credit score. [148] In some cases, in New York City, these judgments will be executed by marshals, public officers who enforce civil court judgments. However, even after an eviction is executed, tenants who repay their arrears may be permitted to remain in their homes. A “permanent eviction” occurs when a tenant ultimately loses their home following an eviction judgment. Eviction data that relies on court records may only give a partial picture of tenants’ housing stability, as some tenants will involuntarily leave their homes without going through this formal court process. This can occur following threats of evictions, a lock out, a mere eviction filing, or harassment by landlords.[149] |

PACT leases permit the new management to begin eviction proceedings for non-payment after 14 days’ notice, and PACT developers can pursue the development’s pre-conversion rent arrears.[150] Responding to a letter from Human Rights Watch, one PACT developer, RDC Development, said that there is “no financial incentive for RDC to evict residents, as we will receive the exact same rent regardless of the tenant’s income.”[151] The eviction process itself is expensive, and in most cases, under PACT, tenant rent contributions are set at 30 percent of household income. Federal subsidy makes up the gap between the tenant’s contribution of 30 percent of their income and the total fixed “contract rent,” set by NYCHA in accordance with HUD requirements, which does not vary based on a household’s income. [152] As a result, there is less of an incentive to evict existing tenants and replace them with higher-income occupants. However, regardless of their household income, tenants must pay 30 percent of their income as rent, and if they fall into arrears, the developer loses revenue. As a result, some developers might believe that aggressively pursuing rent delinquencies, which may lead to more evictions, maximizes the revenue generated by the PACT housing development.

Every PACT developer that Human Rights Watch wrote to concerning eviction rates responded that, before any eviction proceeding is commenced, they conduct outreach to tenants to try to avoid eviction. RDC, the developer for the Ocean Bay PACT conversion, told Human Rights Watch that they are “committed to keeping residents affordably in their homes” and that eviction is a “last resort.”[153]