Human Rights Watch (HRW) welcomes the opportunity to make this submission to the Irish Human Rights Commission (IHRC) in the context of its review of the right to life and legal reform on access to abortion in times of life-threateningpregnancy.

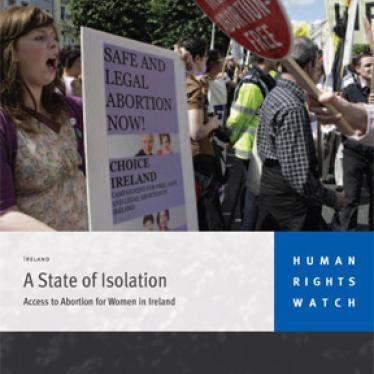

In 2010 HRW investigated the human rights impact of Ireland’s abortion laws and policies, publishing its conclusions in a report, “A State of Isolation: Access to Abortion for Women in Ireland.”[1]We found that Ireland’s current approach to abortion conflicts with its international human rights obligations in a number of respects, and we would encourage the IHRC to consider our findings and analysis in that report in its review.[2]

This limited submission addresses three issues. First, it addresses the question of the immediate and current reform needed to comply with the judgement of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) in A, B, C v Ireland.[3]Second, it describes a few key human rights concerns with Ireland’s current abortion policy regime. Finally, it addresses Ireland’s obligations under international human rights law with respect to abortion. These issues are elaborated in detail in the above mentioned report.

Law reform to comply with A, B, C v Ireland

Human Rights Watch believes that essential steps the Irish government needs to take to comply with the judgment of the ECtHR include the repeal of ss. 58 and 59 of the Offences Against the State Act1861, which criminalize abortion; the adoption of both legislation and regulations to enforce effective and accessible procedures to enable lawful terminations; and the provision of effective recourse for a pregnant woman or girl, at her request, to an independent, competent review panel that can render a timely decision on her rights.

HRW urgesthat the right to lawful termination of pregnancy be addressed through clear legislation and regulations. HRW has extensively documented how the failure to provide clear and adequate legal, administrative and procedural guidance on access to legally sanctioned abortion, creates obstacles and uncertainty that deny women and girls access to lawful treatment and violates human rights.In similar legislative contexts to that of Ireland (e.g. Argentina, Mexico and Peru where access to abortion is restrictive, but may be permitted in circumstances such as where a doctor decides that the pregnancy is life-threatening or is the result of a rape), HRW documented how exercise of the legal right to an abortion was compromised and often denied as the result of lack of legal certainty on how women and girls could access lawful abortions. In too many cases arbitrary denial of access to abortion would lead directly to violations of the right to life.[4] Our findings of the violations caused by lack of a robust framework to ensure effective and accessible procedures for the exercise of the rights of women and girls are consistent with the judgments of the ECtHR in A, B, C v Ireland, Tysiac v Poland,[5]R.R. v Poland[6]andP and S v Poland.[7]They are also consistent with the conclusions of other expert human rights bodies to which Ireland is accountable. For example, in K.L. v Peru,[8]the UN Human Rights Committee (HRC), which oversees state compliance with the ICCPR, examined the situation of a 17 year old girl who was not able to access a legal abortion in a legislative contextthat is similar to Ireland. The Committee held that there had been numerous violations of the girl’s rights, including the prohibition on inhuman and degrading treatment and right to an effective remedy, as a result of the failure to ensure access to abortion allowed by domestic law.[9]

Human rights law also requires that procedures for determining entitlement and access to legal abortion do not create arbitrary barriers that place unnecessary burden on any woman or girl in a crisis pregnancy where her life may be in danger. The UN Special Rapporteur on Health in his report on the interaction between criminal laws and other legal restrictions relating to sexual and reproductive health and the right to health notes that legal requirements which contribute to making legal abortions inaccessible include that abortions be approved by more than one health-care provider. He also warns that conscientious objection laws must not create barriers to access to legal medical treatment. Health care personnel must not be allowed to refuse to provide information about procedures and referrals to alternative facilities and providers.[10]Although human rights law accommodates conscientious objection that cannot justify a refusal to perform a life-saving abortion when no other suitable alternatives exist for a woman to obtain the abortion. Governments have a responsibility to ensure that women and girls can obtain the health care they need and that reasonable alternatives exist when practitioners wish to invoke conscientious objection rules.

Key Human Rights Concerns with Ireland’s Abortion Policies

Inadequate, Inaccurate, and Misleading Information

Failure to ensure access to adequate and accurate medical information constitutes a violation of a number of Ireland’s human rights obligations including the right to receive and impart information, to vindication of one’s personal life, and to health. The Irish government has sought to limit access to information about abortion services, including through the 1995 Regulation of Information (Services Outside the State for the Termination of Pregnancies) Act. By only allowing information about abortion to be provided face to face, the law has a particularly negative impact on women and girls without financial resources for transport to clinics. The lack of accurate information and the 1995 law’s prohibition on direct referrals for abortion have resulted in delays in accessing abortion in other countries, heightening the possibility of health and life-threatening complications.

The difficulty in accessing accurate information on abortion is exacerbated by the existence of so-called “rogue” agencies that the government has failed to regulate. These agencies provide misleading or false information in an effort to delay or prevent abortions. The 1995 act does not apply to organizations that do not give abortion-related information, so these agencies are not held accountable for providing inaccurate information. Human Rights Watch interviewed several women who went to such agencies and were subjected to false warnings about health and other risks from abortion.

Some women are even denied access to prenatal tests that could provide them information about fetal abnormalities, some of which could endanger women’s health or render the fetus nonviable. Human Rights Watch interviewed several women who encountered obstacles in accessing prenatal tests and later discovered that their fetus did have an abnormality incompatible with life. In R.R. v Poland, the inability of the pregnant applicant to obtain timely and accurate information about the health of her fetus, which caused weeks of painful uncertainty and ultimately denied her the right to choose to terminate on the grounds of fatal fetal abnormality, amounted to inhuman and degrading treatment.

Disproportionate Impact on the Poor and Marginalized

The cost associated with traveling abroad for an abortion is a major concern for any woman or adolescent girl with a crisis pregnancy in Ireland, but has a disproportionate impact on the poor. One Irish clinic estimated that the total cost of traveling abroad and paying for an abortion could easily exceed the monthly salary of someone living under the poverty line. An advocate told HRW that poor women and adolescent girls in need of abortion sometimes resort to unscrupulous money lenders or “loans sharks,” and she knew of cases where women unable to repay loans on time were beaten by the lenders.

Women and adolescent girls without work authorization, including asylum seekers, may find the cost of traveling to obtain an abortion entirely out of reach. They face additional costs for applying for emergency temporary travel documents and a visa to enter another country. Many women and girls in the Traveller community have few resources to pay to access abortion services abroad.

Lack of Monitoring

The Irish government does not publish, and does not appear to systematically collect, data on the number of legal and illegal abortions carried out within Ireland. There is no data available about the numbers of women and girls who cannot travel to procure an abortion because they cannot afford to, do not have the necessary travel permissions, or lack information about services outside Ireland.

International Human Rights Law and Abortion

While most international treaties do not explicitly address abortion, authoritative interpretations of core treaties have long established that highly restrictive or criminal abortion laws may violate human rights. This section provides an overview of key international human rights that are at risk when state policies penalize abortion. The analysis below provides examples of UN treaty body general comments and concluding observations on specific countries.[11]

Right to Life

With evidence showing that maternal mortality increases when countries criminalize abortion, it is clear that restrictive abortion laws jeopardize the right to life.[12]The right to life is protected in a number of human rights treaties to which Ireland is a party. For example article 6 of the ICCPR provides: “Every human being has the inherent right to life. This right shall be protected by law. No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his life.”

The HRC has explained that the right to life should not be understood in a restrictive manner.[13]In country-specific concluding observations, the HRC has noted the relationship between restrictive abortion laws and threats to women’s lives in many countries, and has called for removal of abortion penalties.[14]The CEDAW Committee has also repeatedly expressed concern about high rates of maternal mortality due to the inaccessibility of safe abortion services, and asserted that such deaths indicate that governments may not be respecting women’s right to life.[15]

Right to be Free from Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment

Article 7 of the ICCPR states: “No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.” The UN Convention Against Torture (CAT) provides a comprehensive elaboration of this right. The right to be free from cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment is also protected by customary international law.

The HRC has found that some criminal code restrictions on abortion, for example laws prohibiting abortion after rape, have subjected women to inhuman treatment possibly incompatible with article 7 of the ICCPR.[16]The UN CAT has also said that restrictive abortion laws may constitute a breach of the Convention. In its concluding observations on Ireland in 2011, the Committee noted with concern the absence of procedures for establishing whether some pregnancies pose a risk to life, and that women and physicians face prosecution and imprisonment for illegal abortion. It found that this “may raise issues that constitute a breach of the Convention.” It urged Ireland to “clarify the scope of legal abortion through statutory law and provide for adequate procedures to challenge differing medical opinions as well as adequate services for carrying out abortions in the State party, so that its law and practice is in conformity with the Convention.”[17]The Committee has also said that conditioning post-abortion care upon women testifying against themselves in criminal proceedings may constitute a violation of the Convention.[18]It has called on some countries to consider providing exceptions to the criminalization of abortion.[19]

Right to Health

Restrictive abortion laws directly impact the right to health as recognized in a number of international human rights treaties to which Ireland is a party:

- Article 12 (1) of the ICESCR provides that states must recognize “the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.”

- Article 12 (1) of CEDAW provides that “States Parties shall take all appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination against women in the field of health care in order to ensure, on a basis of equality of men and women, access to health care services, including those related to family planning.”

- Article 14(2)(b) of CEDAW provides that states must ensure that women in rural areas “have access to adequate health care facilities, including information, counseling and services in family planning.”

- Article 24 of the CRC provides in article 24 that states must take measures to “ensure appropriate pre- and post-natal health care.”

The UN Committee on ESCR explained in General Comment 14 that the right to health contains both freedoms, such as “the right to control one’s health and body, including sexual and reproductive freedom,” and entitlements, such as “the right to a system of health protection which provides equality of opportunity for people to enjoy the highest attainable level of health.”[20]It recommended that states remove all barriers to women’s access to health services, education, and information, including in the area of sexual and reproductive health.[21]The Committee’s concluding observations on specific countries have recommended that states legalize or eliminate penalties for abortion in some circumstances, such as when the pregnancy is the result of rape or incest, and when the life or health of the pregnant woman is endangered.[22]For states that allow abortion, the CESCR has urged the development of protocols[23]and other measures to remove barriers to legal abortion.[24]It has recommended lowering abortion costs[25]and improving medical and sanitary conditions for carrying out abortions.[26]

The CEDAW Committee in its General Recommendation 24 affirmed states’ obligation to respect women’s access to reproductive health services and to “refrain from obstructing action taken by women in pursuit of their health goals.”[27]It explained that “barriers to women’s access to appropriate health care include laws that criminalize medical procedures only needed by women and that punish women who undergo those procedures.”[28]It recommended that “[w]hen possible, legislation criminalizing abortion could be amended to remove punitive provisions imposed on women who undergo abortion.”[29]In country-specific concluding observations, the CEDAW Committee has recommended that states remove penalties against women who have undergone abortions.[30]It has expressed concern over women’s limited access to reproductive health services and information and called for implementation of laws allowing abortion.[31]In at least one instance, it recommended that the state party provide public funding to women needing abortions.[32]

The Committee on the CRC, in its General Comment No. 4 urged states to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality due to unsafe abortion practices and to ensure access to safe abortions where they are legal.[33]In concluding observations, it has called on states to review legislation prohibiting abortion where unsafe abortions contribute to high rates of maternal mortality, and to remove penalties or expand exceptions to criminalization of abortion.[34]It has recommended that states ensure access to safe abortion for adolescents where legal.[35]

The United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Health issued a report in 2011 addressing how criminalization of abortion violates the right to health. He wrote:

Criminal laws penalizing and restricting induced abortion are the paradigmatic examples of impermissible barriers to the realization of women’s right to health and must be eliminated. These laws infringe women’s dignity and autonomy by severely restricting decision-making by women in respect of their sexual and reproductive health. Moreover, such laws consistently generate poor physical health outcomes, resulting in deaths that could have been prevented, morbidity and ill-health, as well as negative mental health outcomes, not least because affected women risk being thrust into the criminal justice system. Creation or maintenance of criminal laws with respect to abortion may amount to violations of the obligations of States to respect, protect and fulfill the right to health.[36]

The Special Rapporteur also noted that, apart from criminal laws, policies that in effect make abortion inaccessible jeopardize the right to health. These may include laws on conscientious objection for medical providers; laws prohibiting public funding of abortion care; requirements of counseling and mandatory waiting periods for women seeking to terminate a pregnancy; requirements that abortions be approved by more than one health-care provider; parental and spousal consent requirements; and laws that require health-care providers to report suspected cases of illegal abortion when women present for post-abortion care. He noted that these laws especially affect poor, displaced and young women’s access to medical services.[37]

Rights to Nondiscrimination and Equality

The rights to nondiscrimination and equality are set forth in article 2 of both the ICCPR and ICESCR, and CEDAW comprehensively addresses discrimination against women. CEDAW prohibits discrimination against women in the field of health care and in access to health care services. Article 2(f) requires that states “take all appropriate measures, including legislation, to modify or abolish existing laws, regulations, customs and practices which constitute discrimination against women.”

In its General Recommendation on women and health, the CEDAW Committee said, “barriers to women’s access to appropriate health care include laws that criminalize medical procedures only needed by women and that punish women who undergo these procedures.”[38]It also said, “[w]hen possible, legislation criminalizing abortion could be amended to remove punitive provisions imposed on women who undergo abortion.”[39]In its concluding observations on specific countries, the CEDAW Committee has said that restrictive abortion laws may violate the right to nondiscrimination.[40]The HRC has also linked women’s right to nondiscrimination and equality to the availability of reproductive health information and services, including abortion.[41]

Right to Privacy

Article 17(1) of the ICCPR provides: “No one shall be subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to unlawful attacks on his honour and reputation.”

The CEDAW Committee noted in General Recommendation 24 that while breaches of patient confidentiality affect both men and women, they may deter women from seeking advice and treatment for diseases of the genital tract, contraception, incomplete abortion, and in cases where they have suffered sexual or physical violence.[42]The CEDAW Committee has noted that policies that require spousal authorization for abortion impinge on women’s right to privacy,[43]and has recommended that states adopt policies guaranteeing privacy of patients who undergo abortion.[44]

The UN Human Rights Committee has remarked that “where States impose a legal duty upon doctors and other health personnel to report cases of women who have undergone abortion,” this may constitute a violation of a woman’s privacy.[45]The Committee on the Rights of the Child has recommended that governments ensure adolescents confidential medical counsel and assistance without parental consent, including for reproductive health services, when in the adolescent’s best interests.[46]The CESCR has also recommended that states ensure that the personal data of patients undergoing abortion remain confidential.[47]Finally, the Committee against Torture has called for protection of privacy for women seeking medical care for complications related to abortion.[48]

Right to Liberty

Article 9(1) of the ICCPR provides, “Everyone has the right to liberty and security of person. ... No one shall be deprived of his liberty except on such grounds and in accordance with such procedure as are established by law.”

The enforcement of criminal sanctions for abortion constitutes an assault on women’s right to liberty by arbitrarily imprisoning women for seeking to fulfill their health needs. The right to liberty is also threatened when women are deterred from seeking medical care if they fear being reported to authorities by medical professionals. The CEDAW Committee has expressed concern in several concluding observations about women being imprisoned for undergoing illegal abortions, and has urged governments to review their laws to suspend penalties and imprisonment for abortion.[49]

Right to Information

Article 19(2) of the ICCPR states: “Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice.”

The right to information includes both the negative obligation for a state to refrain from interference with the provision of information by private parties and a positive responsibility to provide complete and accurate information necessary for the protection and promotion of rights, including the right to health.[50]Women stand to suffer disproportionately when information concerning safe and legal abortion is withheld.

Right to Decide the Number and Spacing of Children

Article 16(1) of CEDAW provides, “States Parties shall ... ensure, on a basis of equality of men and women . . . (e) The same rights to decide freely and responsibly on the number and spacing of their children and to have access to the information, education and means to enable them to exercise these rights.” By recommending the decriminalization of abortion in specific circumstances, the Committee has recognized that abortion, in certain contexts, may be the only way for a woman to exercise this right.

Right to Freedom of Conscience and Religion

Article 18(1) of the ICCPR provides, “Everyone shall have the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion.” Freedom of religion includes freedom from being compelled to comply with laws designed solely or principally to uphold doctrines of religious faith. It includes the freedom to follow one’s own conscience.

Freedom of religion and conscience is often invoked by health practitioners opposed to abortion, including through the assertion of “conscientious objection” to providing abortion services. As previously noted although the human rights framework accommodates conscientious objection, there are limits. The CEDAW Committee has stated in concluding observations that women’s human rights are infringed where hospitals refuse to provide abortions due to the conscientious objection of doctors.[51]In concluding observations, the CESCR and the HRC have expressed concern about the use of conscientious objection to refuse legal abortions.[52]

Conclusion

HRW urges the IHRC to promote respect for Ireland’s human rights obligations as the government pursues legislative and regulatory reform on abortion. In accordance with Ireland’s human rights obligations, the life and health of the pregnant woman or girl should be the primary consideration in any reforms.

[2]See report op. cit.. Ireland is a party to and legally bound by a number of human rights treaties which all contain relevant guarantees and obligations on the rights of women and girls. These include the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), the Convention Against Torture (CAT) and the Convention the Rights of the Child (CRC).

[3]Application No. 25579/05, Judgment of December 16, 2010, [2010] ECHR 2032

[4]See “Decisions Denied: Women’s Access to Contraceptives and Abortion in Argentina”, June 2005; “Mexico: The Second Assault. Obstructing Access to Legal Abortion After Rape in Mexico”, March 2006; “My Rights, and My Right to Know. Lack of Access to Therapeutic Abortion in Peru”, July 2008;“Illusions of Care, Lack of Accountability for Reproductive Rights in Argentina”, August 2010. These can be accessed at https://www.hrw.org/by-issue/publications/708.

[5]Application No. 5410/03, Judgment of March 20, 2007,ECHR 2007-IV.

[6]Application No.27617/04, Judgment May 26, 2011.

[7]Application No.57375/08, Judgment October 30, 2010.

[8]KL v Peru (2005), Comm. No. 1153/2003, UN Doc. CCPR/C/85/D/1153/2003.

[9]Doctors diagnosed K.L. with an anencephalic fetus and determined that the pregnancy posed risks to her life and health, which entitled her to a lawful abortion. However state hospital authorities ultimately denied K.L. an abortion. Peru was in breach of its ICCPR obligations for denying access to an abortion permitted by domestic law. K.L. experienced depression and emotional distress that the Human Rights Committee deemed was foreseeable and a result of the state’s omission in not enabling her to benefit from a therapeutic abortion.

[10]U.N. Doc. A/66/254, August 3, 2011, para. 24.

[11]There are dozens of additional relevant examples. This submission does not cover European or other regional human rights standards, which we understand will be addressed by other organizations.

[12]World Health Organization, Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidance for Health Systems (Geneva: WHO, 2012).

[13]HRC, General Comment 6, article 6 (sixteenth session, 1982), para. 5.

[14]See, e.g., the HRC’s concluding observations on the Dominican Republic, UN Doc. CCPR/C/DOM/CO/5 (2012), para. 15; Guatemala, UN Doc. CCPR/C/GTM/CO/3 (2012), para. 20; Jamaica, UN Doc. CCPR/C/JAM/CO/3 (2011), para. 14; El Salvador, UN Doc. CCPR/C/SLV/CO/6 (2010), para. 10; Poland, UN Doc. CCPR/C/POL/CO/6 (2010), para. 12; Colombia, UN Doc. CCPR/CO/80/COL (2004), para. 13; Morocco, UN Doc. CCPR/CO/82/MAR(2004), para. 29; Sri Lanka, UN Doc. CCPR/CO/79/LKA (2003), para. 12; and Venezuela, UN Doc. CCPR/CO/71/VEN, (2001), para. 19.

[15]See, e.g., the CEDAW Committee’s concluding observations on Belize, UN Doc. A/54/38, Part II (1999), para. 56; Colombia, UN Doc. A/54/38/Rev.1, Part I (1999), para. 393; and the Dominican Republic, UN Doc. A/53/38/Rev.1, Part I (1998), para. 337.

[16]HRC, concluding observations on Peru, UN Doc. CCPR/C/79/Add.72 (1996), para. 15; and concluding observations on Peru, UN Doc. CCPR/CO/70/PER (2000), para. 20; and Morocco, UN Doc. CCPR/CO/82/CAR (2004), para. 29.

[17]Committee against Torture, concluding observations on Ireland, UN Doc AT/C/IRL/CO/1. (2011), para. 26.

[18]Committee against Torture, concluding observations on Chile, UN Doc. CAT/C/CR/32/5 (2004), para. 6(j).

[19]Committee against Torture, concluding observations on Nicaragua, UN Doc CAT/C/NIC/CO/1 (2009), para. 16; and Paraguay, UN Doc. CAT/C/PRY/CO/4-6 (2011), para. 22.

[20]CESCR, General Comment 14, The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health, UN Doc. E/C.12/2000/4 (2000) (hereinafter General Comment 14), para. 8.

[21]Ibid., para. 21.

[22]See, e.g., CESCR, concluding observations on Peru, UN Doc. E/C.12/PER/CO/2-4 (2012), para. 21; Netherlands (including Curaçao and St. Maarten, prior to independence), UN Doc. E/C.12/NDL/CO/4-5 (2010), para. 27; Sri Lanka, UN Doc. E/C.12/LKA/CO/2-4 (2010), para. 34; Dominican Republic, UN Doc. E/C.12/DOM/CO/3 (2010), para. 29; United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, UN Doc. E/C.12/GBR/CO/5 (2009), para. 25; The Philippines, UN Doc. E/C.12/PHL/CO/4 (2008), para. 31; Kenya, UN Doc. E/C.12/KEN/CO/1 (2008), para. 33; Nicaragua, UN Doc. E/C.12/NIC/CO/4 (2008), para. 26; Costa Rica, UN Doc. E/C.12/CRI/CO/4 (2008), para. 46; El Salvador, UN Doc. E/C.12/SLV/CO/2 (2007), para. 44; Monaco, UN Doc. E/C.12/MCO/CO/1 (2006), para. 23; Malta, UN Doc. E/C.12/1/ADD.101 (2004), para. 41; Chile, UN Doc. E/C.12/1/Add.105 (2004), para. 25; and Kuwait, UN Doc. E/C.12/1/Add.98 (2004), para. 43.

[23]See, e.g., CESCR, concluding observations on Peru, UN Doc. E/C.12/PER/CO/2-4 (2012), para. 21.

[24]See e.g., CESCR, concluding observations on Argentina, UN Doc. E/C.12/ARG/CO/3 (2011), section C; and Mexico, UN Doc. E/C.12/MEX/CO/4 (2006), para. 44.

[25]CESCR concluding observation on Slovakia, UN Doc. E/C.12/SVK/CO/2 (2012), para. 24.

[26]See, e.g., the CESCR’s concluding observations on Azerbaijan, UN Doc. E/C.12/1/Add.104 (2004), para. 56; Chile, UN Doc. E/C.12/1/Add.105 (2004), para. 25; Kuwait, UN Doc. E/C.12/1/Add.98 (2004), para. 43; Poland, UN Doc. E/C.12/1/Add.82, (2002), para. 29; and Russia, UN Doc. E/C.12/1/Add.94 (2003), para. 63.

[27]CEDAW Committee, General Recommendation 24, Women and Health (Article 12), UN Doc. No. A/54/38/Rev.1 (1999) (hereinafter General Recommendation 24), para. 14.

[28]Ibid., para. 14.

[29]Ibid., para. 31(c).

[30]See, e.g., the CEDAW Committee concluding observations on Brazil, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/BRA/CO/7 (2012), para. 29(b); Zimbabwe, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/ZWE/CO/2-5 (2012), para. 34(e); Grenada, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/GRD/CO/1-5 (2012), para. 34(d); Congo, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/COG/CO/6 (2012), para. 36(d); Paraguay, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/PRY/CO/6 (2011), para. 31(a); Mauritius, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/MUS/CO/6-7 (2011), para. 33(a); Côte d'Ivoire, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/CIV/CO/1-3 (2011), para. 41(d); Republic of Korea, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/KOR/CO/7 (2011), para. 35; Djibouti, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/DJI/CO/1-3 (2011), para. 21(b); Costa Rica, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/CRI/CO/5-6 (2011), para. 33(d); Sri Lanka, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/LKA/CO/7 (2011), para. 37(d); Kenya, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/KEN/CO/7 (2011), para. 38(c); Liechtenstein, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/LIE/CO/4 (2011), para. 39(a); Malta, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/MLT/CO/4 (2010), para. 35; Burkina Faso, UN Doc. cedaw/c/bfa/co/6 (2010), para.40(b); Papua New Guinea, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/PNG/CO/3 (2010), para. 42; Malawi, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/MWI/CO/6 (2010), para. 37; United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/UK/CO/6 (2009), para. 289; Japan, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/JPN/CO/6 (2009), para. 50; Timor-Leste, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/TLS/CO/1, para. 38; Rwanda, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/RWA/CO/6 (2009), para. 36; Haiti, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/HTI/CO/7 (2009), para. 37; Honduras, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/HON/CO/6 (2007), para. 25.

[31]See, e.g., the CEDAW Committee’s concluding observations on Algeria, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/DZA/CO/3-4 (2012), para. 41(b); Kuwait, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/KWT/CO/3-4 (2011), para. 43(b); Nepal, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/NPL/CO/4-5 (2011) para. 32(f); Zambia, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/ZMB/CO/5-6 (2011), para. 34(c); Costa Rica, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/CRI/CO/5-6 (2011), para. 33(c); Ethiopia, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/ETH/CO/6-7 (2011), para. 35(a); Tunisia, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/TUN/CO/6 (2010), para. 51; Argentina, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/ARG/CO/6 (2010), para. 38; Botswana, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/BOT/CO/3 (2010), para. 36; Panama, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/PAN/CO/7 (2010), para. 43; Cameroon, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/CMR/CO/3 (2009), para. 41; and Bolivia, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/BOL/CO/4 (2008), para. 43.

[32]CEDAW Committee, concluding observations on Burkina Faso, UN Doc. A/55/38, Part I (2000), para. 276.

[33]Committee on the Rights of the Child, General Comment No. 4 on Adolescent Health and Development, UN Doc. CRC/GC/2003/4 (2003), para. 31.

[34]Committee on the Rights of the Child, concluding observations on Costa Rica, UN Doc. CRC/C/CRI/CO/4 (2011), para. 64(d); and Nicaragua, UN Doc. CRC/C/NIC/CO/4 (2010), para. 59(b); andChad, UN Doc CRC/C/15/Add.107 (1999), para. 30.

[35]Committee on the Rights of the Child, concluding observations on the Republic of Korea, UN Doc. CRC/C/KOR/CO/3-4 (2012), para. 11.

[36]Report of the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Health, UN Doc. A/66/254 (August 3, 2011), para. 21.

[37]Ibid, para. 24.

[38]CEDAW Committee, General Recommendation 24, on article 12 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, Women and Health, UN Doc. No. A/54/38/Rev.1, Part I (1999), para. 14.

[39]Ibid., para. 31(c).

[40]See, e.g., CEDAW Committee, concluding comments on Colombia, UN Doc. A/54/38/Rev.1, Part I (1999), para. 393.

[41]See the HRC’s concluding observations on Argentina, UN Doc. CCPR/CO.70/ARG (2000), para. 14; Colombia, UN Doc. CCPR/C/79/Add.76 (1997), para. 24; Ecuador, UN Doc. CPR/C/79/Add.92 (1998), para. 11; and Guatemala, UN Doc. CCPR/CO/72/GTM (2001), para. 19.

[42]CEDAW Committee, General Recommendation 24, para. 12(d).

[43]See, e.g., the CEDAW Committee’s concluding comments on Indonesia, UN Doc. A/53/38/Rev.1, Part I (1998), para. 284(c) and Turkey, UN Doc. A/52/38/Rev.1, Part I (1998), paras. 184 and 196.

[44]CEDAW Committee concluding observations on Paraguay, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/PRY/CO/6 (2011), para. 31(b).

[45]HRC, General Comment 28, Equality of Rights between Men and Women (article 3), UN Doc. CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.10 (2000), para. 20.

[46]See, e.g. the CRC’s concluding observations on Bulgaria, UN Doc. CRC/C/BGR/CO/2 (2008), para. 47; Georgia, UN Doc. CRC/C/GEO/CO/3 (2008), para. 48; Belize, UN Doc. CRC/C/15/Add.252 (2005), para. 23; Albania, UN Doc. CRC/C/15/Add.249 (2005), para. 57.

[47]CESCR concluding observation on Slovakia, UN Doc. E/C.12/SVK/CO/2 (2012), para. 24.

[48]Committee against Torture, concluding observations on Paraguay, UN Doc. CAT/C/PRY/CO/4-6 (2011), para. 22.

[49]See footnote 13.

[50]See ICESCR, article 2(2) as well as CESCR, General Comment 14, paras. 12(b), and 18-19.

[51]See CEDAW Committee concluding comments on Croatia, UN Doc. A/53/38, Part I (1998), para. 109; and Italy, UN Doc. A/52/38/Rev.1, Part II (1997), para. 353.

[52]CESCR, concluding observations on Poland, UN Doc. E/C.12/POL/CO/5 (2009), para. 28; and HRC, concluding observations on Poland, UN Doc. CCPR/CO/82/POL (2004), para. 8.