Statement by Elise Keppler, Senior Counsel, International Justice Program

Let me begin by expressing my appreciation to the Permanent Mission of the Republic of Azerbaijan for holding an Arria Formula Meeting on the important topic of: The Peaceful Settlement of Disputes, Conflict Prevention and Resolution: Mediation, Judicial Settlement and Justice.

As an organization that monitors human rights in more than 80 countries, Human Rights Watch often encounters heated debate about the relationship between peace and justice. Our brief intervention today thus focuses on this issue.

Justice is an important objective in its own right, including to provide a measure of redress to victims of abuses and to establish a historical record. Investigating and prosecuting grave international crimes, such as war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide is moreover a legal obligation for states under international law.

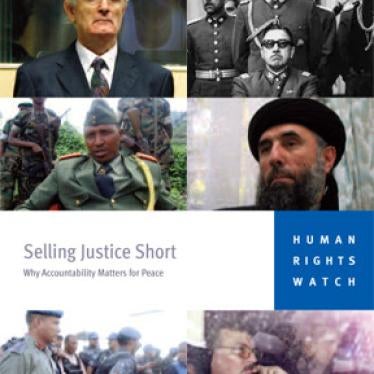

But research over the past 20 years by Human Rights Watch suggests that the impact of justice is too often undervalued when weighing objectives in resolving an armed conflict. This is covered in depth in a report we issued in 2009, “Selling Justice Short,” of which I have brought copies today.

Notably, our research indicates that insisting on justice for grave crimes has not meant an end to peace talks. For example, when the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia issued its indictment for then-Serbian president Slobodan Milosevic in 1999, there was concern that the ongoing conflict in Kosovo would worsen. However, the indictment did not negatively affect negotiations, and Milosevic soon accepted the terms of an international peace plan for Kosovo.

In another example, from 2006 to 2008, negotiations to end the conflict in northern Uganda between the rebel Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) and the Ugandan government progressed and produced detailed agreements on a range of issues despite the lack of “removal” of International Criminal Court (ICC) warrants for LRA leaders. This had been demanded by the LRA, but was not possible. Although the talks later fell apart, many factors aside from the warrants appeared to contribute to this outcome.

In addition, our research indicates that arrest warrants can lead to marginalizing a suspected war criminal, which can facilitate peace and stability. In June 2003, the unsealing of an indictment for then-Liberian president Charles Taylor for crimes committed in Sierra Leone during the opening of talks to end the Liberian civil war was highly controversial. Nevertheless, the indictment delegitimized Taylor both domestically and internationally and helped make clear that Taylor would ultimately have to leave office; this was an issue that had been a potential sticking point in the negotiations, and came to be viewed as helpful in moving the process forward.

More recently, in Libya,some argued that ICC arrest warrants for Muammar Gaddafi, his son Saif al-Islam, and his intelligence chief, Abdullah Sanussi, would discourage Gaddafi from relinquishing power. Yet Gaddafi had made clear even before the warrants that he intended to stay in power until the bitter end. If anything, the arrest warrants hastened Gaddafi’s downfall by signaling to his coterie that they had no political future with him and were better off defecting.

In Syria, some countries reportedly are reluctant to mention a possible ICC referral on the belief that this could spoil any hope of a negotiated settlement. However, firm assertions of an ICC role would put Syrian officials and commanders on notice that they could also be held responsible for crimes they commit. This might encourage defections and stigmatize those who stand in the way of a negotiated solution.

Finally, foregoing accountability often does not lead to hoped-for peace and stability. The current situation regarding Bosco Ntaganda in eastern Congo is a case in point. Ntaganda, a former rebel commander, is the subject of an ICC arrest warrant since 2006. Despite the warrant, he was made a general in the Congolese army in early 2009, with President Joseph Kabila explicitly stating that he considered Ntaganda to be “an important partner for peace in the Kivus.”

Since Ntaganda was awarded a military post, the troops loyal to him have continued to carry out numerous attacks on civilians, including during military operations conducted by the Congolese army. This April, after the government indicated it might arrest him but failed to act, Ntaganda deserted the army and became associated with a new rebellion in the Kivus. Human Rights Watch has documented how Ntaganda and his forces once again are recruiting children in their ranks in the context of this new round of fighting. This is the very crime for which he is wanted by ICC since 2006.

In the short term, it is easy to understand the temptation to forego justice in an effort to end armed conflict. Butthese examples illustrate that the anticipated negative consequences of pressing for accountability often do not come to pass, while ignoring atrocities can carry a high price. Indeed, peace built on impunity all too often leads to renewed cycles of violence and new atrocities. These lessons should be prominent in working out settlements of conflicts that will truly foster long-term stability based on respect for human rights and the rule of law.

Thank you.