(Geneva) – The Sudanese authorities are increasingly deporting Eritreans to their country without allowing them to claim asylum, Human Rights Watch said today. On October 17, 2011, Sudan handed over 300 Eritreans to the Eritrean military without screening them for refugee status, drawing public condemnation from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

The mass deportation follows dozens of other unlawful deportations by Sudan since May of Eritrean asylum seekers and of Eritreans who had been denied access to asylum.

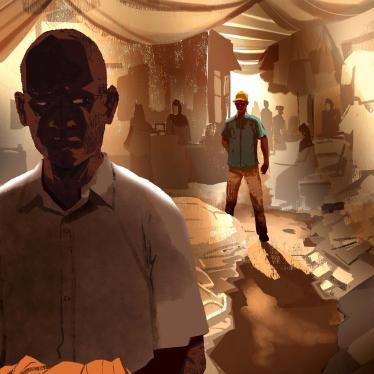

Eritrea, ruled by an extremely repressive government, requires all citizens under 50 to serve in the military for years. Anyone of draft age leaving the country without permission is branded a deserter, risking five years in prison, often in inhumane conditions, as well as forced labor and torture. UNHCR considers that in practice the punishment for desertion or evasion is so severe and disproportionate, it constitutes persecution.

“Sudan is forcibly returning men, women, and children to certain detention and abuse in one of the world’s most brutal places,” said Gerry Simpson, senior refugee researcher and advocate at Human Rights Watch. “Sudan has no excuse and should immediately end these deportations.”

On September 12, media reports said Sudanese police had arrested 317 Eritreans, including 65 women and four children, who had been trying to cross from Sudan into Egypt. UNHCR says the authorities confirmed a week later that at least 300 Eritrean nationals had been detained in Dongola prison, in Northern State, about 400 kilometres south of Sudan’s border with Egypt. Other sources put the total at 351, including about 100 women.

Sudan’s Commission on Refugees (CoR), the Interior Ministry entity responsible for registering refugees, issued assurances that the group would be relocated to Khartoum for screening purposes and that any asylum seekers or refugees would be transferred to Shagarab refugee camp near Kassala in eastern Sudan, one of 12 camps there that shelter around 70,000 refugees.

UNHCR says it was taken by surprise when it discovered the group had been handed over to the Eritrean authorities in Tesseney, on the Sudan-Eritrea border near Kassala. According to an Eritrean aid worker from an international charity who spoke by phone with one of the deportees during the deportation, the Sudanese authorities used seven buses to drive the group from Dongola to the border with Eritrea via Khartoum and Kassala, without stopping.

The same aid worker, with contacts in Tesseney, said that once they had been handed over to the Eritrean military in Tesseney, the military took them in six buses and trucks to a nearby military base.

Under international refugee law, asylum seekers have a right to claim asylum, which applies regardless of how they enter a country or whether they have identity documents.International law forbids countries from deporting asylum seekers without first allowing them to apply for asylum and considering their cases.

UNHCR says it has no information on the treatment in Eritrea of those deported on October 17 or in the previous months and that it is still trying to obtain the names of those deported.

No international agencies in Eritrea, including UNCHR, are able to monitor the treatment of Eritreans deported back to Eritrea. However, Eritrean refugees in various countries have told credible sources that Eritreans forcibly returned to their country are routinely detained and mistreated in detention.

UNHCR’s official Guidelines to States on the protection needs of Eritrean asylum seekers state that “individuals of draft age who left Eritrea illegally may be perceived as draft evaders upon return, irrespective of whether they have completed active national service or have been demobilized” and that “the punishment for desertion or evasion is so severe and disproportionate such as to amount to persecution.”

The October 17 mass deportation followed at least five incidents since May 2011 in which Eritrean asylum seekers, or Eritreans who had been denied access to asylum procedures, were arrested in Sudan’s eastern Kassala State and then deported. Nongovernmental organizations from around the world had condemned these deportations during UNHCR’s executive committee meeting in early October.

According to UNHCR, Sudan deported at least 24 registered Eritrean asylum seekers at various times between May and July. On July 26, UNHCR publicly condemned Sudan's deportation of six Eritreans the previous day, after they were denied the opportunity to claim asylum. Two of them jumped off a truck carrying them to the Eritrean border. As a result, one died and the other was seriously injured.

UNHCR also said that on September 15, Sudan deported four Eritreans whose asylum request had been ignored by the court ordering their deportation. Sudan deported another six Eritreans on September 18 after charging them with illegally entering Sudan.

Thousands of Eritreans use smugglers every year to travel from Eritrea through Ethiopia and Sudan to reach Egypt, from which many then try to reach Israel or the European Union. The smugglers cross Sudan’s 1,273-kilometer border with Egypt through informal border points.

“After decades of hosting tens of thousands of Eritreans in eastern Sudan, the authorities have suddenly started to crack down on some of the world’s most vulnerable people,” Simpson said. “Sudan should publicly reaffirm its commitment to protecting Eritreans’ right to seek asylum and not to be returned to persecution.”