Q. Who is Umar Israilov?

A. Umar Israilov was involved in the Chechen insurgency in the early 2000s. The indictment in the case of his suspected killers says that he was seized in Chechnya in 2003, held in secret detention at the home base of Ramzan Kadyrov - who at the time was head of one of Chechnya's security services and who is now Chechnya's leader-tortured personally by Kadyrov, and compelled to join Kadyrov's forces. In 2004 Israilov escaped Chechnya. Chechen forces abducted his father, Ali, and held him in secret detention for nearly 11 months in an effort to convince him to make his son return to Chechnya. Israilov later received asylum in Austria. He filed a complaint with the European Court of Human Rights against Russia for his abduction and torture, and in it named Kadyrov as one of his torturers. On January 13, 2009, several armed men tried to kidnap Israilov as he was walking home from a grocery store in Vienna. His kidnappers, all three of them Chechens who had asylum status in Austria, shot him dead as he tried to escape.

Q. What is this trial about?

A. The indictment says it's about the political murder of Israilov. The trial is to determine the guilt of three men in custody who stand accused of the crime. They have been indicted on charges of attempted "abducting and deporting a person to a foreign power" (§ 103 Austrian Criminal Code); and murder ( § 75 Austrian Criminal Code). Two of the three are also accused of forming a criminal organization.

Q. What does this trial have to do with today's Chechnya?

A. It's connected in two ways. First, directly--the prosecutor argues that the crime was planned after one of the perpetrators, who goes by the name Otto Kaltenbrunner (he changed it from his original name, Ramzan Edilov), traveled to Chechnya and met with Kadyrov. Second, the Israilov case sheds light on the torture, enforced disappearances, collective punishment, and other unlawful methods the Russian government has for years been allowing the authorities in Chechnya to use in fighting the insurgency there.

In a June 2010 report, Dick Marty, rapporteur for the Committee on Human Rights and Legal Affairs of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, flagged the Israilov case as one that he attempted to raise with Kadyrov during Marty's March 2010 trip to Chechnya.

[See paragraphs 39-42: http://assembly.coe.int/Main.asp?link=/Documents/WorkingDocs/Doc10/EDOC12276.htm]

Q. How does the prosecution link the crime to the government in Chechnya?

A. The prosecutor contends that the three people under indictment-Kaltenbrunner, Suleiman (Muslim) Dadayev and Turpal-Ali Yesherkayev-- tried to abduct Israilov with the express purpose of delivering him to the Chechen authorities. He also contends that the kidnapping was ordered "on behalf of the Chechen republic." He points out that in the summer of 2008, Israilov was approached by a man who said he was sent by Kadyrov and who threatened harm to Israilov and his family if he did not withdraw his torture complaint and return to Chechnya. Shortly thereafter the emissary, Artur Kurmakaev, contacted the Vienna police. He told them that he was working for Kadyrov, that Kadyrov had "ordered him to find Israilov and to return him," the indictment says, and that after Israilov refused, "Kadyrov allegedly called [Kurmakaev] and told him it was no longer necessary to return Israilov to Chechnya," which Kurmakaev understood to mean that Israilov should be killed. Kurmakaev was ordered to return to Slovakia, from where he had entered Austria illegally after having submitted an asylum request to the Slovak authorities. After again entering Austria illegally (and asking for asylum in Austria and then withdrawing this request), Kurmakaev was detained and deported-allegedly voluntarily-to Russia in June 2008. There has been no information about his fate or whereabouts since early 2009.

Q. Were the kidnappers acting alone?

A. The indictment includes information about the involvement of two other key figures. One is Lecha Bogatirov, whom it identifies as the gunman who shot and killed Israilov, and who escaped to Russia just after the murder. The indictment says he will be dealt with in a separate case. It also includes information about the key role played by Shaa Turlaev, whom it describes as one of Kadyrov's "closest confidants," and as having been "actually sent [to Austria in October 2008] by Kadyrov to make members of the Chechen disaspora return home, if necessary by force."

The indictment states: "It seems likely that a further reason why Turlaev visited Kaltenbrunner was the failure of Artur Kurmakeav's mission: meaning it was Kaltenbrunner who was now responsible for Israilov's "return" to Chechnya."

Turlaev stayed with Kaltenbrunner during his October 2008 trip to Vienna.

Q. Where are Bogatirov and Turlaev, and why are they not indicted?

A. Their whereabouts are unknown, although the indictment suggests that Bogatirov is probably in Russia, in Chechnya. The Viennese counterterrorism police report had named Bogatirov and Turlaev as accomplices. The indictment says Bogatirov is being treated under a separate case. It is not clear why Turlaev has not been indicted.

Q. Who is Ramzan Kadyrov and what's his connection to all of this?

A. Kadyrov is the Kremlin-appointed leader of Chechnya. The indictment states that in June 2008 he sent an emissary to threaten Israilov so that he would drop the European Court of Human Rights complaint and return to Chechnya. It also says that "it has not been possible to determine whether [Shaa] Turlaev was the driving force behind [Israilov's kidnapping and murder] or whether he only acted as Kadyrov's emissary and passed on orders."

Israilov accused Kadyrov of torturing him, and told The New York Times that he had witnessed how Kadyrov had tortured other people in a makeshift secret detention facility in the gym on his villa. This was in 2003, when Kadyrov was chief of security for his father, Akhmed Kadyrov, who at the time was president of Chechnya. Akhmed Kadyrov was killed in a bomb attack in 2004, after which Ramzan Kadyrov rose to become prime minister of Chechnya, and then, in 2007, president.

Q. What is the human rights situation in Chechnya today?

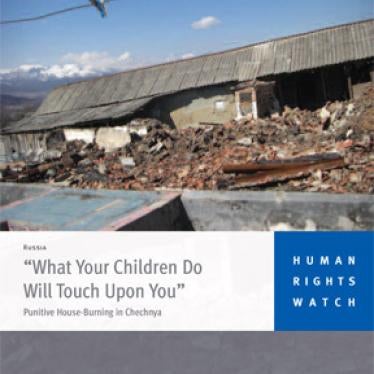

A. Russian and international human rights organizations have documented persistent human rights abuses in the context of the counterinsurgency campaign in Chechnya. Law enforcement and security agencies under Kadyrov's de facto control are implicated in the enforced disappearances, torture, and extrajudicial killings of those suspected of having any connection with the insurgency. There is an open policy of collective punishment, and government officials, including Kadyrov, have said that relatives of presumed insurgents should expect to be punished if their family members who are involved in the insurgency do not surrender. Human rights organizations have documented a distinct pattern of house burnings by security forces to punish families for the alleged actions of their relatives and to compel these relatives to surrender.

Victims of rights violations and human rights defenders who seek to hold perpetrators to account have been threatened, abducted, and even killed.

On July 15 2009, the most prominent Chechen human rights activist, Natalia Estemirova, was abducted in Chechnya and murdered. Estemirova worked on some of the most sensitive human rights cases for the Memorial Human Rights Center. The circumstances of her murder, along with a pattern of threats against her, Memorial, and independent activists and journalists in Chechnya, all point to possible official involvement or acquiescence in her murder. Journalist Anna Politkovskaya, who had documented torture and other abuses in Chechnya, was murdered in 2006.

In August 2008, another alleged victim of torture in Chechnya, Mokhmadsalakh Masaev, was abducted in Chechnya several weeks after the publication of an interview in which he described his torture and illegal detention in a secret prison allegedly run by Kadyrov in his home village. To date, Masaev's fate and whereabouts remain unknown.

Several other high-profile killings have also been linked to the Chechen leadership. Adam Delimkhanov, a close associate of Kadyrov and current member of the Russian parliament, is wanted by Interpol in connection with the murder of Suleyman Yamadayev-a former commander of an important pro-Kremlin Chechen military battalion whose family had been in a feud with Kadyrov-in the United Arab Emirates in 2009 [http://www.interpol.int/public/ICPO/PressReleases/PR2009/PR200942.asp]. A failed murder attempt on Suleyman's brother Isa has been connected to Turlaev in media reports citing anonymous sources in the Russian prosecutor's office [http://www.kommersant.ru/doc.aspx?DocsID=1351122]. A third Yamadayev brother, Ruslan, was murdered in Moscow in 2008.

Kadyrov openly and publicly threatens violence against his perceived enemies.

The Chechen authorities have banned women who refuse to wear headscarves from working in the public sector. Female students are also required to wear headscarves in schools and universities. Though these measures have not been codified into law, they are strictly enforced and publicly supported by Ramzan Kadyrov. Kadyrov articulated clear approval of a series of paintball attacks on uncovered women in June 2010.

Q. What has the Austrian government done to investigate further the possible connections between the Chechen government and this crime?

A. It is not clear whether the Austrian prosecutor's office or any other Austrian law enforcement or security agency has sought information from Russia about the crime or about the involvement of Kadyrov, Turlaev, or Bogatirov. It is known only that the Russian authorities determined Bogatirov's home address in Russia, which it provided to the Austrian authorities after the latter issued an international arrest warrant for Bogatirov.

Q. What has the Russian government done to investigate the possible connections between the Chechen government, and Kadyrov, and this crime?

A. It is unclear what steps, if any, the Russian government has taken to investigate any possible connection between Kadyrov and his associates with the Vienna murder. Israilov's father wrote to Russia's prosecutor general to ask it to open an investigation into his son's murder, referring to-among other things-- the threats made by Kurmakaev. The prosecutor's office responded that it would be in contact with the Austrian authorities, but did not respond to further correspondence inquiring about what had been done.

Overall, Russia's federal authorities have failed to hold the Chechen leadership accountable for human rights violations.