Mario Pacheco came to the United States when he was two months old. He lived as a lawful permanent resident for 20 years with his parents in Chicago, where he attended public schools, got his GED, and went to work immediately afterward. But he was convicted for possession of 2.5 grams of marijuana (about two joints' worth) with intent to distribute and was ordered deported as a result.

On Oct. 17, the Houston Chronicle reported on the Department of Homeland Security's decision to put cases like Mario's at the back of the line and to make it a priority instead to deport immigrants with serious, violent felony convictions. Four days later, U.S. Sen. John Cornyn, R-Texas, and six other senators wrote to the department to express their concern about this policy shift. They wrote that DHS should not be "selectively enforcing the laws against only those aliens it considers a priority."

Their concern is misguided.

Currently, deportation cases pass through immigration courts based on the order that Homeland Security takes people into custody. Thus far, it has had no criteria at all for making some cases priorities for quicker action. The result has been that some people convicted of violent felonies, including those who are in the United States unlawfully, have remained in the country, while some long-resident legal immigrants who have made positive contributions to their communities - even served in our military, started businesses, or volunteered in soup kitchens - end up getting deported.

A deportation system without criteria is a poor use of taxpayer funds: it can threaten public safety and goes against important human rights principles. Human rights law requires immigration courts to consider a person's ties to his country of residence, like length of residence, family relationships, business, educational, or community contributions, and the relative seriousness of his or her criminal conviction. The status quo does none of these things.

Current immigration law makes little distinction between a variety of crimes - it treats passing a forged check just as seriously as murder. In addition, judges are prevented from even considering the reasons why a person should remain in the country. In these cases, deportation is mandatory.

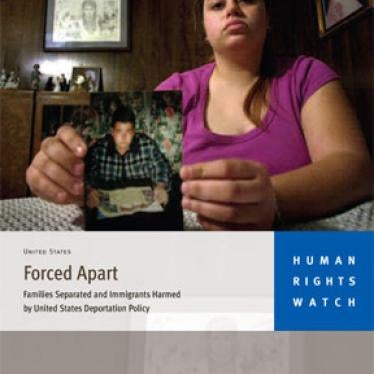

In our 2007 report "Forced Apart," Human Rights Watch reported on multiple cases where long-time residents were prevented from presenting their military service, family or community ties as arguments against their deportation. We documented the case of Ricardo S., a construction worker married to a U.S. citizen who faced deportation due to a minor drug possession charge that resulted in no jail time. We also reported on the case of Joe Desiré, a long-time legal resident who served in the U.S. military in Vietnam but faced deportation due to drug charges. Each of them was facing deportation because DHS took them into custody before other immigrants, including those who may have been convicted of more serious, and more violent, crimes.

Good governance demands the effective use of finite resources. This is particularly true during economic downturns. Every move to deport a child, a student, or a long-time legal resident convicted of a petty offense means less money available to deport someone with a violent criminal conviction.

In fiscal year 2009, the Obama administration oversaw the deportation of 393,289 people - more than any other year in the history of the country. But even as the number of deportations grows, so grows the backlog in immigration cases, currently at more than 250,000. If the system is going to serve the best interest of U.S. citizens, the government has no choice but to identify some cases as priorities.

DHS is beginning to do just that. The agency is putting more emphasis on immigrants with convictions for violent crimes.

But serious shortcomings remain. Government data reveal a history of failure to set priorities for spending DHS' deportation dollars. Human Rights Watch found that 77 percent of immigrants who had been in this country legally and who were deported between 1997 and 2007 on criminal grounds were deported for nonviolent offenses, like shoplifting or possession of marijuana. Even under Homeland Security's recent Secure Communities program, which was specifically created to target immigrants convicted of violent crimes, 80 percent of those deported had been identified through the program due to a nonviolent or noncriminal offense.

Senators should not oppose efforts to begin smart immigration enforcement. They should applaud them.

Ginatta is the advocacy director for the U.S. Division of Human Rights Watch.