(OSH) - "They don't stop beating me. Please, sell your house, your car, your last things to get me out of here." Nafiza (not her real name) recalls the words from memory, written by her 37-year-old son in a letter smuggled out of prison by a policeman who took her bribe. Nafiza's youngest son, 15, is still recovering from his own 24-hour ordeal at the hands of Kyrgyzstan's police, who hung him by his arms from the ceiling and repeatedly beat him with a rifle butt.

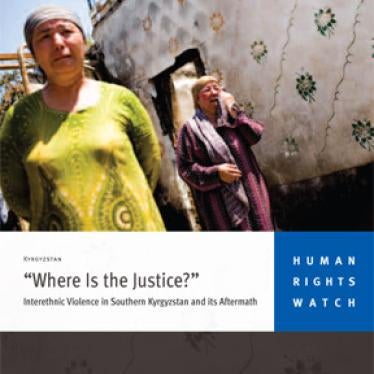

One month after both her boys were taken from their home in Osh, in southern Kyrgyzstan, Nafiza sits crying into her lap, petrified that talking to an outsider will get her son killed and asking me what she should do to help him.

The authorities are blaming and punishing her son and other Uzbeks for instigating the violence that ripped through the country's south last month. Hundreds of people - both Kyrgyz and Uzbeks - were killed and thousands injured, and thousands of Uzbek businesses and homes were burned down.

Nafiza would like to leave Kyrgyzstan to escape the growing crackdown on ethnic Uzbeks here. But with the Uzbek-Kyrgyz border-just a stone's throw away-closed indefinitely, she is stuck. And so are many other ethnic Uzbeks here.

When the violence erupted in Osh on June 10, almost 100,000 ethnic Uzbeks fled across the officially closed border into Uzbekistan, and 300,000 others escaped to other parts of Kyrgyzstan.

But after 14 days, Uzbekistan - hardly known for championing human rights - and Kyrgyz officials used fearmongering tactics to induce the refugees to return home. They warned that if the refugees didn't vote in a June 27 constitutional referendum, they would be regarded as saboteurs of peace. They also said that people not returning right away could lose their homes and citizenship, and might never be allowed to return.

Despite fears for their safety, almost all crossed back into Kyrgyzstan.

But their fears turned out to be well founded. In the weeks after the refugees returned to their destroyed neighborhoods, hundreds of ethnic Uzbek families in Osh faced arbitrary arrests, detention, beatings, and torture by Kyrgyz law enforcement and security agencies.

The authorities claim the arrests are simply part of the investigation into the June violence. But dozens of ethnic Uzbeks-some still incapacitated and in pain from serious injuries sustained in detention-told me about police and military violence, including torture.

Torture and arbitrary detention, sadly, are longstanding problems in Kyrgyzstan, but the massive targeting of ethnic Uzbeks for unlawful arrest and mistreatment amid ethnic insults and threats of renewed violence is new. And it is instilling profound fear among the already traumatized ethnic Uzbeks.

Thousands of those with the financial resources have fled to Russia to escape the ever-present threat of arrest and abuse and to earn money there to help rebuild their shattered lives. Despite potential extortion by corrupt law enforcement officials in the Osh airport or at checkpoints on the road north to the capital, those who can afford to leave are the lucky ones.

But the majority are stuck here. Afraid to leave the crumbling ruins of their homes, let alone their street, they move only in groups and cars, if at all. They gather in parts of town near the Uzbek border, which they hope to cross if violence re-erupts.

So why wait until the last minute before crossing? In a single day, I spoke to more than 100 families, most of whom said they wanted to flee but feared arrest on the way there, being pushed back, or even shot at by Kyrgyz and Uzbek border guards, and being denied help in Uzbekistan.

And indeed Kyrgyzstan is preventing its own nationals from crossing the border, in line with Uzbekistan's official blanket ban on Kyrgyz nationals accessing its territory, a breach of Uzbekistan's obligations under international law, which prohibits it from closing its borders to people directly fleeing persecution.

On July 22, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe agreed to send "without delay" an international force of 52 police to monitor and advise their Kyrgyz counterparts, with the goal of restoring public order and trust. Nafiza and tens of thousands of other ethnic Uzbeks eagerly await them, but now the Kyrgyz government is refusing so sign the memorandum of understanding required for their deployment. Meanwhile, ethnic Uzbeks' fear of further violence and nowhere to escape remains. Opening the borders on both sides, ending the arbitrary arrests, and requests from Uzbekistan to the UN refugee agency and other agencies to help refugees who cross the border would help.

With tensions still running high in Osh and the resumption of violence remaining a real possibility, there is no time to lose if further bloodshed is to be avoided.