(Jerusalem) - The Israeli government should immediately stop the arbitrary destruction of Palestinian homes and other property in the West Bank and compensate the people it has displaced, Human Rights Watch said today. Israeli authorities destroyed 141 Palestinian homes and other buildings in July 2010, the largest number in any month since at least 2005, and have already carried out dozens of demolitions in August.

"While Israel is demolishing more and more Palestinian homes, it continues to subsidize the Jewish settlements nearby," said Sarah Leah Whitson, Middle East director at Human Rights Watch. "Israel has flouted international law not only by supporting settlements on occupied territory, but also by erasing longstanding Palestinian communities next door."

In one example, Israeli military authorities recently demolished Al Farisiye, a farming community of roughly 135 people in the northern Jordan Valley that had been inhabited by Palestinians for generations. On July 19, Israeli authorities demolished 76 structures in Al Farisiye, displacing approximately 113 people, including 52 children. The authorities had ordered them to evacuate on June 24, emphasizing that their homes had been built in a "closed military zone," according to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). While the area indeed had been designated as "closed" since the late 1960s, Al Farisiye village was established before the designation and has been inhabited until the present.

Israeli authorities delivered further eviction orders on the same grounds on July 31, and then on August 5, razed 10 more structures that housed 22 people and demolished 27 emergency tents that displaced residents had set up after the first round of demolitions, OCHA reported.

The Israeli Civil Administration Authority (CAA) acknowledged in an email on August 8 that property had been destroyed but said that at most 10 buildings had been demolished. It was not clear if the spokesman was referring to the demolitions on August 5, July 19, or both. Human Rights Watch observed large numbers of demolished buildings at the site. Some of the Palestinian families whose homes and property Israeli authorities destroyed had been living in their village for at least 50 years.

The CAA delivered a third round of eviction orders on August 15 and 16 to three families in Al Farisiye, all of whom had lost property during the prior demolitions and had erected donated tents on the sites of their former homes, according to OCHA. Two of the families took down the tents themselves in response to the order.

Since 1967, the Israeli government has established four settlements within five kilometers of Al Farisiye for Jewish Israeli citizens and has continued to authorize housing construction, apart from a partial, 10-month "freeze" on new settlement housing that will expire in September, and to provide heavy subsidies for settlement there.

The demolitions in Al Farisiye are part of a sharp recent increase in Israeli forced evictions of Palestinians living in homes that the Israeli government contends are "illegal" in the 60 percent of the West Bank under full Israeli civil and military control known as "Area C." On July 19, the Israeli daily Haaretz reported that the Defense Ministry had instructed the CAA, the military agency that carries out demolitions in the West Bank, to step up enforcement against "illegal" Palestinian structures there. On March 2, Haaretz reported, Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu told a government committee that Israel would never cede control over the Jordan Valley in any future peace deal due to its strategic importance along the eastern border of the West Bank.

In total, Israeli authorities have destroyed 267 Palestinian homes and other structures in the West Bank and East Jerusalem so far this year, as compared with 271 in all of 2009, 236 in 2008, and 208 in 2007, according to OCHA. In most cases these buildings were destroyed due to the lack of an Israeli building permit, which is nearly impossible for Palestinians to obtain.

Demolitions in Al Farisiye

Members of the Israel Defense Forces and the CAA delivered 13 eviction orders to families in Al Farisiye at about 5 a.m. on June 24, residents told Human Rights Watch. The military orders stated that the families were living in a "closed military zone" and gave them 24 hours to leave.

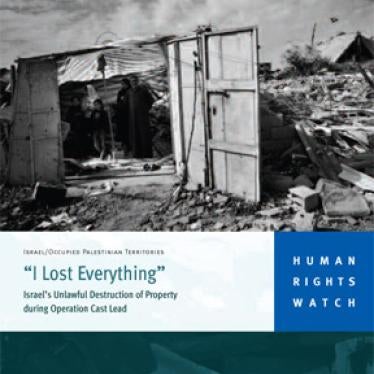

At 6 a.m. on July 19, a large number of Israel Defense Forces jeeps, two bulldozers, and several white cars belonging to the CAA arrived in Al Farisiye and officials forcibly removed Palestinian residents from their homes, residents told Human Rights Watch. The bulldozers then destroyed 26 residential structures, 24 animal pens, 8 traditional underground ovens, and 12 outhouses and water tanks, according to observations by Human Rights Watch and OCHA reports.

Saleh Dababat, 58, saw the Israeli bulldozers demolish his animal pens and the home where he lived with his wife and two children. "They came at 6 in the morning, surrounded us and demolished our homes in front of our eyes," he told Human Rights Watch. Dababat, who said that he was born and lived in the area all his life, was trying to retrieve some of his food, belongings, children's clothes, and schoolbooks from under the rubble of his home when Human Rights Watch spoke with him.

Adnan Dababat, a 63-year old resident of Al Farisiye, told Human Rights Watch, "I have been living here for more than 40 years, and now they've destroyed my home and buildings, our wood oven and drinking water tank. They even bulldozed my stores of sugar and wheat." He lost 11 structures, including his house, animal pens, a sanitation structure, and a water tank, OCHA reported. He was in the West Bank town of Tubas, 14 kilometers away, when Israeli authorities delivered the eviction order for his home by posting it on one of his buildings.

Residents of Al Farisiye said that on July 31, after the first round of demolitions, Israeli authorities delivered two new eviction orders on the same basis. According to OCHA, the orders gave the occupants of residential buildings housing 17 persons, including 7 children, 24 hours to evacuate their homes.

Witnesses told Human Rights Watch that at 6:20 a.m. on August 5, two bulldozers, 10 army jeeps, and several CAA cars arrived and began to demolish 10 more structures, as well as between 25 and 30 tents that had been distributed to residents by the International Committee of the Red Cross and the Palestinian Authority (PA) after the first round of demolitions, as well as 30 trees that had been planted to replace destroyed ones.

The military eviction orders could not be challenged within the Israeli military court system. Abd Allah Hammad, a lawyer from the Jerusalem Center for Legal Aid and Counseling who is representing the families, and Tawfiq Jabarin, another lawyer familiar with evictions in the area, said that the only legal alternative open to the Palestinian villagers is to bring a challenge in a civil court inside Israel. Villagers said they could not afford legal expenses and that they had requested PA representatives in the town of Tubas to arrange for legal assistance from a non-profit organization. According to Hammad, the PA did not notify him of the eviction orders until it was too late to request an injunction from the Israeli High Court of Justice.

The Israeli civil court system apparently denies most such efforts to halt evictions. Human Rights Watch spoke to three Palestinian lawyers and two researchers from Israeli non-profit organizations who said they were not aware of cases where the court had ruled in favor of Jordan Valley residents against military eviction or demolition orders. In January, for example, the Israeli High Court of Justice ruled against the appeal of residents of Khirbet Tana, a village near Nablus, where demolitions displaced 100 people. In another example, in December 2006 the High Court rejected the appeal of families facing demolition orders in the Bedouin community of Al Hadidiye on the grounds that they posed a security risk to the neighboring settlement of Ro'i.

Even if the court granted residents a temporary stay of the demolition orders, under Israeli military laws and planning procedures, it would be extraordinarily difficult and costly for residents to gain recognized ownership and building rights to the land, by proving, for example, that no Palestinian with a property interest was an "absentee" at the time Israel occupied the area in 1967, and that any buildings on the site were in accordance with Israeli-approved plans.

"The lives of these Palestinians, living under the Israeli military's full control, are utterly insecure," Whitson said. "Within weeks they went from being residents of a generations-old community, to watching their homes bulldozed, with no real opportunity to challenge the destruction."

Closed military zones

The office of the Israeli military advocate general did not respond to Human Rights Watch's request for clarification about why Al Farisiye was demolished. After Israel occupied the West Bank in 1967, it did not grant residents of Al Farisiye permits or otherwise recognize their property rights and declared the area a "closed military zone," which civilians would not be able to enter, live in or leave without permission.

The Israeli newspaper Haaretz reported that the Israeli army had set up a warning sign at the entrance to Al Farisiye a year ago, and quoted a CAA statement that the authorities had declared the area a "live fire zone." The CAA has previously evicted Palestinians from such "firing" or "training zones" in other parts of the West Bank on the basis that military training posed a serious danger to them.

It was not clear, though, why such orders affected Al Farisiye and not any of the nearby settlements, such as Rotem (established in 1983), which lies less than one kilometer away. Like Rotem, the settlement of Mehola (established in 1979), about two kilometers away, was built on lands that Al Farisiye residents said they rented from a Palestinian landowner who lived in Tubas.

Israeli authorities have also given a second rationale for destroying Palestinian property in closed military zones, saying it is to evict people they do not classify as "permanent residents." Under Israeli military order 378, from 1970, the government may evict persons living in a "closed military zone" without any administrative procedures. Section 90(D) of the order states that "permanent residents" can remain in an area designated as closed, and that eviction orders cannot change their status as permanent residents. Israeli authorities have argued that they may evict Palestinian residents who do not continuously inhabit a closed military zone, since they are not "permanent residents." There is no provision in the military order allowing the military to evict permanent residents from closed military zones that are later designated as "firing" or "training" areas.

In the August 8 email to Human Rights Watch referenced above, the spokesperson for the Israeli Civil Administration said that no one was living in the buildings destroyed in Al Farisiye either on the days that the eviction orders were delivered or on the days of the demolitions. The owners inhabited the demolished structures only seasonally for a few days each year, the spokesman contended, but own permanent homes elsewhere. The spokesman also stated that Israel does not recognize Al Farisiye as an inhabited location in its population registry.

Residents of Al Farisiye told Human Rights Watch that they inhabited the area year round and did not own residences elsewhere. Human Rights Watch visited the community and observed destroyed furniture, kitchen utensils, and other possessions indicating residential use of several structures, and spoke to human rights workers and residents of other areas in the Jordan Valley who confirmed that Al Farisiye had been inhabited for decades. As the Israeli NGO Bimkom has pointed out, an Israeli census in 1967 defined as a "community" any location with 50 or more permanent residents - a definition applicable to Al Farisiye.

Aref Daraghmeh, head of the Al-Malih and Bedouin Communities in the Jordan Valley Council, which includes Al Farisiye, witnessed the second demolition on August 5. "People were scattered and had to shelter with their family and friends elsewhere," Daraghmeh told Human Rights Watch. "A whole army came to destroy the homes of people with nothing, while the settlements are developed every day."

In addition to demolishing Palestinian buildings in areas designated as closed military zones, Israeli authorities routinely refuse to grant Palestinians permits required for all new construction, for any alterations to existing buildings or infrastructure, and even for existing buildings. The CAA rejected 94 percent of Palestinian building-permit applications in the West Bank from 2000 to 2007, according to government figures.

"Palestinians are living in a Kafkaesque nightmare, seeing their homes demolished because they don't have the right permits while almost every single one of their permit applications is rejected," Whitson said. "Israel's feeble claim that it is only enforcing the rules does nothing to mask the cruel policy of discrimination that lies behind these home demolitions."

Demolition of Palestinian homes, support for settlements

By contrast, Israel has granted Jewish settlements control over extensive areas of the West Bank. Settlers participate in planning settlements with Israeli authorities, while no Palestinian representatives serve on the CAA planning bodies. Israel has in many cases liberally granted settlers permission to construct new buildings, including retroactively authorizing their construction.

Al Farisiye, like the nearby Israeli settlements of Rotem, Maskiot, Mehola, and Shadmot Mehola, lies within "Area C," which comprises 60 percent of the occupied West Bank and over which Israel retains near-total control under the Oslo Agreements of 1995. According to an OCHA study, "only around one percent of the land in Area C is available for Palestinian construction," while Israel has granted settlements control over about 70 percent of Area C and permitted extensive construction and expansion.

Al Farisiye lies on lands that Israel has granted to the "regional council" of Jordan Valley settlers. Various Israeli government ministries list the northern Jordan Valley as a "national priority" area, and settlers receive substantial subsidies for a range of activities, including buying land, developing agriculture and tourism, and educating their children.

Israeli authorities both issue and execute many more demolition orders against Palestinians than against Jewish settlers in the occupied West Bank. From 2000 to 2007, Israeli authorities carried out 1,663 of 4,993 demolition orders for illegal construction that were issued against Palestinians, but only 199 of 2,900 orders against settlers, according to government figures.

Israel continues to authorize settlement housing construction and to provide incentives to settlers, notwithstanding a partial settlement "building freeze" scheduled to expire in September. According to Israeli statistics, 415 settlement housing units were completed between January 1 and March 30, 2010, while 2,361 units were under construction, Peace Now reported.

Israeli authorities had previously demolished structures in Al Farisiye, but never on such a large scale, residents said.

Residents of Al Farisiye, which dates to at least the 1950s, are primarily engaged in agriculture and sheep herding. They told Human Rights Watch that Israeli restrictions on building infrastructure to service the village had made their lives difficult even prior to the recent demolitions. Residents had no electricity or running water, and had to purchase water in tankers at high cost. Haaretz reported that Israeli authorities prohibited Al Farisiye residents from using wells dug in the area by the Israeli Mekorot Water Company, and confiscated their water pumps four months ago after destroying pipes for drinking water that the villagers had extended several years earlier to a nearby stream.

Residents were forced to leave Al Farisiye temporarily after Israeli authorities cut off their access to water earlier this year, Haaretz reported. Human Rights Watch observed a destroyed water-tank, which Adnan Dababat said was among the structures demolished on July 19.

Other July demolitions

Israel demolished numerous other Palestinian homes in the occupied West Bank in July. On July 19, Israeli authorities demolished a water-collecting pool and confiscated irrigation pipes used to irrigate a plot of land in Al Baq'a Valley east of Hebron. The land supported a family of 17, including 14 children. Three family members were injured in the course of the demolitions, the UN reported.

On the same day, Israeli authorities demolished a house extension and an animal pen on the outskirts of Hebron, affecting a family of nine, including seven children. On July 20, OCHA reported, Israeli authorities demolished two homes, six animal pens, and a tent belonging to eight Palestinian families, including 38 children, in Luban Al-Gharbi, a Palestinian village northwest of Ramallah, near the Israeli settlements of Beit Aryeh and Ofarim.

All these demolitions were apparently carried out on the grounds that the Palestinian structures did not have building permits. The only alternative that Israeli authorities offer Palestinian owners who are served with eviction orders is to demolish the property themselves.

In East Jerusalem, on July 28, the Jerusalem municipality demolished Palestinian-owned plant nurseries, a car wash, and a hardware store in Ard Wad Emjalley, near the Hizma checkpoint, on the grounds that they were built without permits. The demolished businesses were the main source of income for five Palestinian families, about 65 people, including 35 children, according to OCHA. In addition, the municipality either damaged or confiscated large amounts of construction materials, estimated by OCHA to be worth several hundred thousand shekels.

Israeli and municipal authorities have allocated only 13 percent of East Jerusalem for Palestinian construction, compared with 35 percent for Israeli settlements. While Israel has built 50,000 housing units for Jewish settlers in East Jerusalem, it has built virtually none for Palestinians, according to Israeli nongovernmental organizations.

A 2009 study by UNICEF, the World Health Organization, and the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees found high levels of stunted growth, lack of adequate food, and poverty among Palestinian herding communities in Area C. The report concluded that "the root cause of vulnerability in Area C" was Israeli administrative and military restrictions that effectively prohibited the construction or repair of many structures including homes, barns, roads, water pipes, and electricity pylons, and that excessively prohibited the movement of Palestinians, blocking many of their traditional roads while barring them from new roads constructed for settlers.

Applicable international law

Israel's legal obligations on this issue derive from both international human rights law and international humanitarian law. The source of these laws can be found in both customary international law and treaties such as the International Covenants on Civil and Political Rights and on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICCPR and ICESCR), the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949, and the 1907 Hague Regulations, all of which the International Court of Justice has found apply in the West Bank.

The rights at stake include the right to a home, to housing, to property, and to be free from discrimination in the exercise of these rights. Article 17 of the ICCPR requires Israel to respect the right of everyone to a home. This means any interference with a person's home life must not be arbitrary - that is, it must be based on clear law, be non-discriminatory, and must give the person a fair hearing to challenge any interference on these rights.

Any interference must be for legitimate reasons and must be strictly proportional - that is, the least restrictive means of obtaining that aim. Eviction and destruction of a family's home requires very strong justification. The Human Rights Committee, the international expert body that interprets the ICCPR, has said that the relevant domestic legislation on interference with the right to a home "must specify in detail the precise circumstances in which such interferences may be permitted."

The prohibition against discrimination is spelled out in Article 2 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and codified in the major human rights treaties that Israel has ratified, including the ICCPR, the ICESCR, the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD), and the CRC. Discrimination is defined as resulting from laws, policies, or practices that treat persons in similar situations differently due to, among other criteria, race, ethnic background, or religion, without adequate justification.

The ICESCR requires Israel to respect the right to adequate housing. In its General Comment 4, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which monitors the compliance of states parties to the ICESCR, stated that "the right to housing should not be interpreted in a narrow or restrictive sense which equates it with, for example, the shelter provided by merely having a roof over one's head or views shelter exclusively as a commodity. Rather it should be seen as the right to live somewhere in security, peace, and dignity."

It stated that forced evictions "can only be justified in the most exceptional circumstances." The Committee's General Comment 7 found that where otherwise lawful, such evictions should be carried out only on the basis of clear laws, should not leave people homeless, and should use force only as a last resort. Unlawful forcible evictions should be punished.

Under the Fourth Geneva Convention, which governs occupied territories, an occupying power may carry out total or partial "evacuation" of an area only if "the security of the population or imperative military reasons so demand." In any event, any population so evacuated must be transferred back to its homes as soon as the hostilities in the area have ceased, and in the meantime the occupying power must ensure those evacuated have "proper accommodation."

The right to respect for one's property is set out in Article 17 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which says "no one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his property". Article 46 of the 1907 Hague Regulations states that the occupying power must respect private property, which cannot be "confiscated." Article 53 of the Fourth Geneva Convention says "destruction" by the Occupying Power of private property is prohibited unless "absolutely necessary" in military operations.

In international jurisprudence on the right to property, courts, including the European and Inter-American Courts of Human Rights, have concluded that states must recognize as property the individual, family, and group traditional use and occupation of buildings and lands, even where such property rights have not been formally recognized in property registries. Interference with property rights is allowed only when there is clear domestic law, the interference is for a legitimate aim, the interference is the least restrictive possible, and adequate compensation is paid. Permanent seizure or destruction of property can be justified only where no other method is possible and compensation is paid.