(New York) - The election of a prominent human rights activist to the presidency of the Supreme Court Bar Association of Pakistan is a victory for human rights in Pakistan and for the country's transition to genuine civilian rule, Human Rights Watch said today. The election of Asma Jahangir on October 27, 2010, will make her the first woman to lead the country's most influential forum for lawyers.

Jahangir is one of Pakistan's most respected human rights activists, credited with establishing the highly regarded independent Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) and AGHS Legal Aid, the first free legal aid center in Pakistan. She was placed under house arrest by Gen. Pervez Musharraf, the former military ruler, when he imposed emergency rule in 2007. She played a prominent role in the "lawyers movement" in Pakistan, which led to Musharraf's ouster and to the restoration to office of Supreme Court Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry.

"The election of Asma Jahangir to head the prestigious Supreme Court Bar Association will no doubt infuriate those who have opposed her decades-long principled advocacy for human rights and constitutional government," said Ali Dayan Hasan, senior South Asia researcher at Human Rights Watch. "The election honors not only Jahangir's unflinching integrity, but also all of those in Pakistan who struggle daily to promote the rule of law."

From 1998 to 2004, Jahangir served as the United Nations special rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary, or arbitrary executions. From 2004 until July 2010, she was the UN special rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief. She resigned as chairperson of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan in July to run for the Supreme Court Bar Association presidency.

Human Rights Watch said that it is important to have someone of Jahangir's stature heading the country's top bar association, especially because relations between the judiciary and some of its allies in the "lawyers movement" have deteriorated markedly in the past year. Since Chaudhry's restoration, lawyers who supported him have demanded, and often gained, an improper say in judicial decisions, appointments, and transfers, Human Rights Watch said.

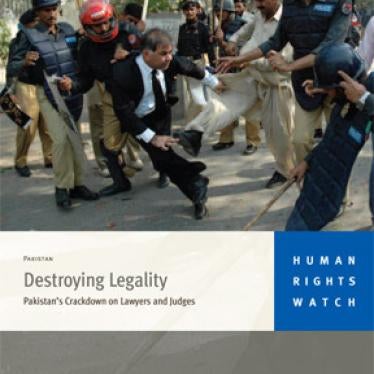

In October, lawyers tried to attack the chief justice of the Lahore High Court in his chambers. The following day, the chief justice allowed provincial police to enter the court, where they beat and arrested about 100 lawyers. The lawyers were charged under the country's draconian Anti-Terrorism Act.

During her campaign for the Supreme Court Bar Association, Jahangir emphasized the need to create professional distance between lawyers and the judges they helped restore to office in 2009. She emphasized that the rule of law required judiciary to be independent of government interference as well as non-partisan in dispensing justice.

Jahangir repeatedly received threats during her campaign for raising issues such as corruption in the legal arena. On October 24, a previously unknown group calling itself the Khatme-Nabuwat Lawyer's Forum issued pamphlets declaring Jahangir an apostate and urging lawyers not to vote for her. Apostasy is a capital offense under Pakistani law.

"Although independent of the executive, Pakistan's judiciary has been woefully inadequate in dispensing justice free of interference from pressure groups that helped restore judges to the bench," Hasan said. "The election of a person of Jahangir's stature and integrity will help ensure that the judiciary meets high judicial standards and rejects interference from lawyers seeking to cash in real or perceived favors."

Human Rights Watch urged Jahangir, who is well known as a free speech advocate, to use her new office as the representative of Pakistan's most influential lawyers to call upon the courts to stop muzzling media criticism of Pakistan's judiciary.

Journalists have told Human Rights Watch that major television channels were informally advised by judicial authorities that they would be summoned to face contempt of court charges for criticizing or commenting unfavorably on judicial decisions or specific judges. Publications including the English-language newspapers Dawn and the News were ordered to apologize publicly to the court, and Dawn faced contempt proceedings for publishing a story alleging misuse of office by the chief justice of the Sindh High Court.

"Judicial independence does not mean that judicial decisions, or even the judges themselves, should not be subject to public criticism," Hasan said. "The Supreme Court should send the message that no government institution is immune from public debate in a democratic society."