I met Purna Bahadur Sunuwar in early March 2004. It was two weeks after his 15-year-old daughter Maina had been abducted by soldiers from their home in the Kavre district of Nepal, east of the capital Kathmandu. As we sat in his mud house and he told his story, Purna could not hold back tears. He was clear that the army had acted out of vengeance.

Almost three weeks earlier, on 12 February, government troops had killed Maina's cousin Reena Rasaili, alleging that she was a Maoist insurgent in the civil war that had torn the country since 1996. Maina's mother, Devi Sunuwar, was at Reena's house that night. She found the courage to speak to the media and human-rights activists, telling them that her niece had been raped and murdered by the security forces.

The army was quick to retaliate. Nepali soldiers arrived at the Sunuwar family home on 17 February, looking for Devi. They found only her husband and daughter there. They seized Maina, and told Purna Bahadur to come to the local Panchkhal army camp the next day with his wife, saying: "If you come tomorrow, we will know you are innocent, and if you don't come we'll know you are guilty."

The family complied with this threatening order, and arrived at the camp the next day accompanied by local-government officials. But officers at Panchkal denied any knowledge of Maina, telling the family that no one was detained there. The family then visited numerous government offices, but without making success. It was at this time that I visited the Sunuwars' home. "Nobody has told us so far where our daughter is", her father lamented.

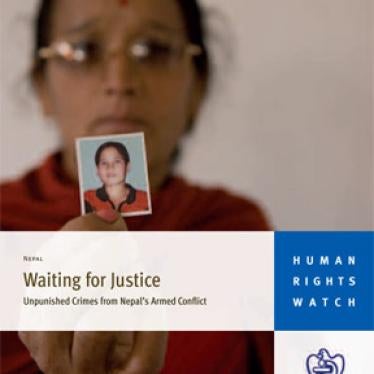

Maina's unexplained disappearance is but one symbol of the widespread violations perpetrated by the army during Nepal's decade-long civil war that claimed 13,000 lives before it was ended with a "comprehensive peace agreement" in November 2006. Many families are, like that of Purna Bahadur Sunuwar, waiting for justice.

The block

The transition from war to peace and a political settlement in Nepal has been difficult. Even the election in April 2008 of a new constituent-assembly charged with drafting a new constitution - which was won by the Maoists' political party and led to the establishment of a coalition government - has not been able to resolve the country's deep-rooted differences.

An important outstanding issue has been the integration of the combatants of the (Maoist) People's Liberation Army into the regular army. There is some progress here after four years of dispute since the 2006 agreement, with a start to the discharging of former child soldiers who had remained attached to the Maoist army and been held in cantonments. Now they can get on with rebuilding their lives.

Beyond this process there remains doubt over whether Nepal's leading political forces - the Maoists, other political parties, and the army - are willing to take the hard decisions needed to rebuild the country, or whether they will plunge Nepal back into crisis and possibly another round of conflict. Nepal's friends and allies abroad must decide whether and how to press these forces to act in a constructive spirit.

Nepal's political evolution since the peace deal underscores the need for action. Many Nepalis hoped that the government formed after the April 2008 elections would usher in a new era, breaking the feudalism of a discredited and discarded monarchy and setting the country on a path of development to alleviate some of Asia's most entrenched poverty.

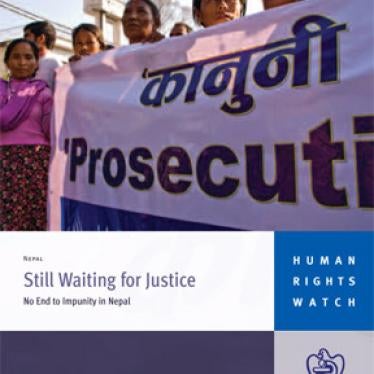

Instead, the various political parties descended into vicious wrangling for power and position. The needs of governance have been made hostage to a standoff between the two real power-holders: the Maoists (who quit the government in May 2009) and the army. One consequence of this gridlock is a failure to address the serious human-rights abuses committed by both sides during the conflict. The power-games in Kathmandu leave justice and accounting for past atrocities in limbo.

In these circumstances, the family of Maina Sunuwar is symbolic of the thwarting of the hopes of 2006 by political calculation, uncertainty and lack of will.

The process

Two months after Maina Sunuwar disappeared in February 2004, a message from the Nepali army headquarters in Kathmandu informed her mother that Maina had been killed and that her clothes and other materials things had been sent to the police. In March 2005, diplomatic pressure led the army to form a board of inquiry charged with investigating Maina's fate. The board heard testimony from thirteen people, including army officers; it concluded that after being subject to repeated near-drowning and electric-shocks, she had died in custody the day that she was taken from the family home. In fact, when Maina's family arrived at the army camp looking for her, she had already been buried there.

The board recommended that a court-martial be convened to try three officers for Maina's death. This, one of the few human-rights cases to go to trial, opened in September 2005. But it ended in a travesty of justice, for the officers were found guilty only to the lesser charges of using inappropriate interrogation techniques and of disposing of Maina's body improperly. The sentence of six months in prison proved no punishment, since they had already spent that period confined to barracks during investigations and were as a result set free.

The Nepali armed forces have repeatedly claimed that their own military-justice system can best prosecute "internal" wrongdoers. The fact that the process, including court-martial proceedings, is closed to the public always cast doubt on these claims. The Maina Sunuwar case was clinching evidence that the system failed to deliver justice.

Maina's family, outraged by the farcical outcome, filed a complaint with the civilian police against the three military officers - and named another, Captain Niranjan Basnet, who had been present when Maina was taken. In March 2007, the United Nations office of the high commissioner for human rights helped the police exhume Maina's body. The supreme court then issued an order that Maina's case should be investigated within three months. In January 2008, the public prosecutor in Kavre district filed murder charges against the four army officers (including Basnet). But none of the four was arrested, and they failed to appear for trial.

In September 2009, the district court ordered the army to suspend Basnet, who had since been promoted to major, and asked army headquarters to submit all the files containing the statements recorded during the military court of inquiry. The army has to date refused to comply; it contends that, despite the supreme-court's ruling, civilian courts do not have jurisdiction over military personnel.

A further bizarre aspect of this case is that even while the murder charges were pending against Niranjan Basnet, he was sent on a UN peacekeeping mission to Chad. In December 2009, when the UN discovered that the major had been charged with involvement in Maina's torture and murder, he was shipped back to Nepal and placed by the army in military custody - though the army still refuses to produce him for trial.

The wait

This unresolved situation places a particular responsibility on those countries - Britain, the United States and India - which played a significant role in bringing the conflict in Nepal to an end, and which had halted military assistance to Kathmandu out of concern over human-rights violations. These countries, like the Nepali people themselves, would like to see the country embark on a path toward development. But it cannot be right that support for development comes at the cost of accountability.

India has already resumed partial military assistance to the Nepali army, and Washington is engaged in discussion on the same issue.

The British army's chief-of-staff, General David Richards, visited Nepal in February 2010 and stated there that his government would review its military aid to Nepal. He also urged the government to address allegations of human-rights abuses, including the case of Maina Sunuwar, only to be rebuffed by Nepal's defence minister Bidhya Bhandari; the minister said that human-rights activists were making "unnecessary accusations" and that the three soldiers found guilty in the Maina case by the army's internal court "had already been punished."

Nepal's government and army have consistently failed to investigate, prosecute and punish soldiers who committed serious violations of human rights. This is reason enough for influential countries to be careful in their dealings with the authorities in Kathmandu - and to continue to seek justice for Maina Sunuwar.

Purna Bahadur Sunuwar, Maina's father, died heartbroken in October 2009. Maina's mother is still waiting. Maina's remains are in a forensic laboratory, her last rites are yet to be performed. Her killers remain free.

Meenakshi Ganguly is senior South Asia researcher at Human Rights Watch.