Still Waiting for Justice

No End to Impunity in Nepal

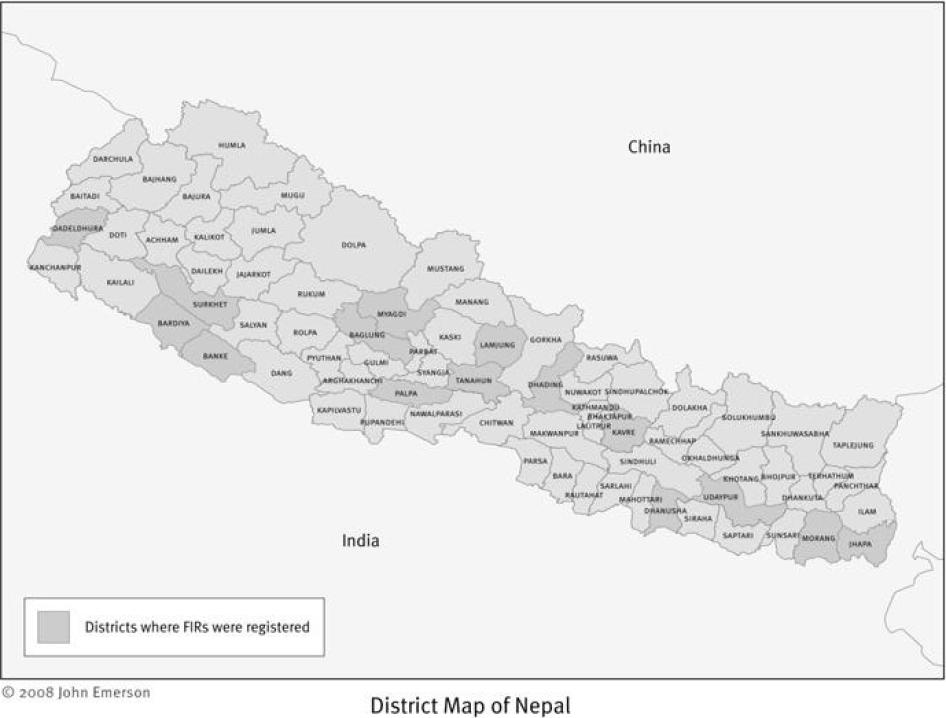

Map of Nepal

Summary

The Government is committed to establishing constitutional supremacy, to ensuring the rule of law and good governance, to implementing the understandings and agreements [associated with the peace process], and to providing a positive conclusion to the peace process by eliminating anarchy, insecurity, and impunity.

Policies and Programmes of the Government of Nepal for the Fiscal Year 2009 — 2010, as presented to parliament on July 9, 2009, unofficial translation.

There is no justice in Nepal, no rule of law and no government but I want to see a Nepal where even the senior most government officials cannot escape justice. The security officials must be punished, they are not employed to kill citizens. All those responsible for human rights violations must be brought to justice.

— Dhoj Dhami, uncle of Jaya Lal Dhami, killed by security forces in February 2005, Kanchanpur, September 18, 2009

Three years after a historic peace agreement ended a decade-long armed conflict, specifically promising greater respect for human rights and accountability, impunity remains firmly entrenched in Nepal. No member of the security forces or the Maoists has been held to account in civilian courts for grave human rights abuses committed during the conflict; most cases that have been filed are stalled. Human rights violations committed since the end of the conflict also continue to go unpunished: cases against suspects are routinely withdrawn, with the victims offered token amounts of money. Ending impunity for past and continuing violations is essential if Nepal is to continue to move away from violence and more firmly establish the rule of law.

One emblematic case is the torture and death in army custody of 15-year-old Maina Sunuwar, (Case 31 in the Update on Pending Cases below), in February 2004. Sunawar’s mother, when offered NRs100,000 (US$1,307) compensation for her daughter’s death and suffering, said, “If there is liberty of killing a human being on payment of NRs1 lakh, the right to life has no meaning at all."

This report is a follow-up to our 2008 report, Waiting for Justice: Unpunished Crimes from Nepal’s Armed Conflict, and provides updates on the 62 cases highlighted there. Despite official commitments to end impunity, and intensive litigation and campaigning by families of those killed or disappeared during the armed conflict of 1996–2006, no one has been arrested, let alone brought to justice in civilian courts, for the crimes we documented. Only in a couple of cases, including that of Maina Sunuwar, military tribunals have convicted soldiers on minor charges and handed out weak punishments.

After the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) (CPN-M, the former armed group which declared the “people’s war” in 1996), won Constituent Assembly elections in April 2008, the political consensus vanished and was replaced by an increasing lack of trust between the main political parties. As a result, there was little or no progress in the peace process.

At another level, all the political parties (including the CPN-M) have put pressure on the police not to investigate certain cases in order to protect their members. Institutions long opposed to accountability—most notably the Nepal Army—have dug in their heels and steadfastly refused to cooperate with ongoing police investigations. Nepal Army assurances that army officers responsible for human rights violations will be excluded from United Nations peacekeeping duties or from being promoted appear meaningless, since the army not only makes no efforts to investigate the worst abuses but indeed resists such investigations by police. Furthermore, the army command has recently nominated for promotion several officers suspected of being responsible for grave human rights violations. Among the Maoists elected to the Constituent Assembly are alleged perpetrators of human rights abuses who are under police investigation.

As a result of political instability, the Constituent Assembly (which also functions as the parliament, formally called the Legislative-Parliament) has been largely paralyzed. Key legislation to put in place transitional justice mechanisms as well as initiate reform of the criminal justice system has not progressed.

As the evidence presented here demonstrates, the quest of family members of victims for justice and clarity on what happened to their loved ones continues to be blocked by both de facto and de jure impunity. De facto impunity refers to the state’s failure to prosecute human rights offenders under existing laws due to factors such as lack of political will or pressure from perpetrators. De jure impunity occurs when laws are either vague, or explicitly permit offenders to escape punishment.

De Facto Impunity: Problems Remain

Analysis of developments in the past year on the 62 cases shows continuing obfuscation and failure by state authorities to initiate meaningful investigations and prosecutions relating to past grave human rights abuses. All 62 cases are, or were, the subject of formal complaints lodged with police in 49 different First Information Reports (FIRs), which the police are charged with investigating.

Only in the case of Maina Sunuwar have the authorities filed charges, and then only under the pressure of sustained campaigning and litigation. However, although the police and public prosecutor identified four army officers as suspects in that case, murder charges were brought in absentia. Despite the court issuing arrest warrants, to date police have not arrested the suspects. Very recently, on September 13, 2009, the court ordered the army to suspend one of the accused and to submit all the documentation it has on the case to the court.

In the case of Manoj Basnet (Case no. 44) who was killed by the Armed Police Force (APF) in Morang, in August 2005, litigation to compel the authorities to properly investigate has come to an end. The APF was able to influence the victim’s father not to proceed with the case through the offer of jobs and money. Advocacy Forum tried to convince the Supreme Court to reverse the decision, pleading public interest, but the court quashed the petition.

In several other cases, relatives are losing hope and are no longer actively pursuing the case, tired of constantly fighting obstacles put in their way by the police and other authorities. Bhumi Sara Thapa, mother of Dal Bahadur Thapa and Parbati Thapa, (Case nos. 5 and 6), told Advocacy Forum on September 20, 2009:

When I filed a First Information Report with the police, I had hoped that my family would get justice; the accused would be punished and my family would receive compensation for the living and education of my children. Although it has been years since I started struggling for justice, nothing has happened yet. I have visited the police station many times but there has been no progress in investigation. I don't have much hope because I think the government is reluctant to provide justice.

In one of only two cases concerning victims of Maoist abuses, the family is no longer actively seeking to register the FIR, possibly as a result of threats.

After the Maoist-led government, in August 2008, announced that it would compensate “victims of conflict,” some relatives suspended their pursuit of criminal investigations, fearing that doing so might negatively influence their applications for compensation.

However, the large majority of the relatives of the 62 victims highlighted in this report continue their fight for justice, despite repeated delays and obstacles erected by the authorities.

In ten cases, the local police have still refused to register FIRs, sometimes in the face of a court order to do so. A ruling by the Supreme Court in the disappearance of Sanjeev Kumar Karna and four other students in Dhanusha district, where the court directed the police to register and proceed with investigations, should have solved this matter. Instead the Dhanusha District Police Office informed Advocacy Forum that it would not act on any conflict-related FIRs and that such FIRs have been filed away separately. The Dhanusha police continue to refuse to file FIRs in several other cases.

In 24 other cases, though FIRs were registered, there is no sign of investigations being conducted. In some of these cases, families have sought two writs of mandamus (an order from a superior court directing a government official to perform a duty correctly), the first one to force the police to register the FIR; the second to get a court order for the police to proceed with investigations. Despite two court orders, there are still no meaningful investigations.

In the case of three men who all were killed under the same circumstances in Morang district, in September 2004, the police finally registered a FIR in October 2008, in one case after being ordered to do so by the Biratnagar Appellate Court. The police continue to refuse to file FIRs relating to the other two, forcing the families to also file mandamus petitions, despite the precedent established by the court ruling in the companion case.

In approximately 13 cases, police have seemingly endeavored to proceed with investigations, sending letters to relevant agencies to seek their cooperation to interview the alleged perpetrators. However, the army, Armed Police Force, and Maoists have constantly refused to cooperate. In the killing of Arjun Bahadur Lama (Case no. 32) who was last seen in the custody of members of the Maoist CPN-M party, the Kavre police finally filed an FIR and began investigations to identify the whereabouts of the alleged perpetrators after the Supreme Court ordered them to do so, but without cooperation from the Maoist leadership, police have had no success to date in locating the suspects. Purnimaya Lama, wife of Arjun Lama, told Advocacy Forum on September 22, 2009:

I once met Prachanda, [the chairman of Unified Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist)]. He promised that he would uncover the truth about my husband and then inform me, but I have received no information yet although I have tried to meet him again several times.

Attempts by relatives to force the police either to register an FIR or, if registered, to proceed with investigations by petitioning the courts for writs of mandamus have proved largely unsuccessful. On June 18, 2009, Advocacy Forum assisted 28 families across 13 districts to file petitions. The responses from the police and public prosecutors have varied but show similar patterns of neglect and delay in different districts.

In their responses to the Baglung Appellate Court in three cases, both the district police and public prosecutor informed the court that, “charge sheets can be filed only if investigations find evidence,” and that filing of charges is a decision of the Attorney General’s Office. On that basis, they sought the annulment of the petitions. However, to the best of the families’ knowledge, police have not initiated any investigations to date and Advocacy Forum lawyers have not been able to find evidence of progress in any of the three files.

The authorities’ use of these arguments in court appears to be an attempt to side-step the fact that no investigations have actually been conducted and police have gathered no evidence. In other cases police and public prosecutors have so far simply failed to respond. Jay Kishor Labh, father of Sanjeev Kumar Karna (Case no. 15), told Advocacy Forum on September 22, 2009:

Even after the Supreme Court's order of February 3, 2009, the District Police Office, Dhanusha has not registered the FIR according to law. Although I have visited the DPO at least on 3 different occasions and met the deputy superintendent and the superintendent of police there, there has not been any progress in the investigation of the case. I don't think the police are willing to work in accordance with the law.

In yet other cases, particularly from Kavre district, police claim they are not proceeding with investigations because the court has not returned the file the police were ordered to submit to the courts after the writ was filed. A similar argument has been used by the Morang police in the killing of Sapana Gurung and another related case where police claim investigations cannot proceed because the Parliamentary Probe Committee has not returned the file.

There appears to be a lack of consistency in how these cases are dealt with by the Appellate Courts and Supreme Court. Though the Supreme Court has ordered the police to proceed with investigations in the high-profile cases of Maina Sunuwar and Arjun Bahadur Lama, in other cases it has repeatedly postponed hearings. As Bhakta Bahadur Sapkota, father of Sarala Sapkota (case no. 14) told Advocacy Forum on September 22, 2009:

I think the court has postponed the hearing of my petition because the judges do not know about my daughter’s inhuman killing. If the media had written a lot about the killing, the judge would have known about the case and would have given it priority for hearing.

The Appellate Court in Nepalgunj when considering mandamus petitions in five cases brought with the help of Advocacy Forum expressed skepticism regarding the likelihood of its writs being acted upon when Supreme Court orders were not followed even in high-profile cases like that of Maina Sunuwar.

The Biratnagar Appellate Court has been particularly inconsistent in the way it has handled mandamus petitions. For instance, in the case of two men killed together in October 2005, the court refused a petition on behalf of one of them, while ordering the DPO to register a FIR on behalf of the other.

The underlying reasons for the lack of effective investigations by police are already discussed at length in Waiting for Justice. An important factor is the esprit de corps between the army and the police. In informal conversations with individual police officers, other reasons mentioned include instructions from higher police officers not to investigate cases involving soldiers; fear that the government might change and the army again be in power, putting the police officers concerned at risk; and considerable difference in rank between the junior police officers often responsible for these investigations and senior army officers named in the FIRs. A sub-inspector of police in Pokhara who wishes to remain anonymous told Advocacy Forum on September 20, 2009:

There are many cases of human rights violations filed before the police. As the people implicated are often high-ranking officials, it is difficult to investigate the cases because of their influential positions.

This once again reinforces the recommendation made in Waiting for Justice that a separate specialized police unit should be set up to conduct these investigations, staffed by senior officers.

De Jure Impunity: The Disappearances Bill and Truth and Reconciliation Commission Bill

None of the three governments in power since the peace agreement was signed have introduced any changes to the laws that impede effective criminal investigations into past human rights violations. These laws include the State Cases Act, Army Act, Police Act, Evidence Act, Commission of Inquiry Act, Public Security Act, and Muluki Ain (Nepal’s traditional legal code). There has been little or no progress toward establishing the transitional justice mechanisms called for in the peace agreement despite pledges by all three governments to set these up.

The current 22-member coalition government committed to addressing impunity in the formal “Policies and Programmes” it presented to parliament on July 9, 2009. It stated:

The national security policy will be formulated in keeping with the suggestions of the Legislative-Parliament and political consensus. The national peace and rehabilitation commission, the high-level truth and reconciliation commission, the high-level state structuring suggestions commission, [and] the commission for the investigation of the disappeared will be constituted/re-constituted. The act of monitoring the implementation and compliance of the understandings and agreements will be done by the national peace and rehabilitation commission.[1]

Prime Minister Madhav Kumar Nepal in his address to the UN General Assembly on September 26, 2009, reiterated that the government “was determined to” set up a commission to investigate “disappearances.”[2]

During its time in power, the UCPN-M[3] in November 2008 released the Disappearances (Crime and Punishment) Bill, but the bill was never tabled and discussed in the parliament. Provisions in the Bill—including the definition of enforced disappearances and the punishments provided for violations—fell short of international human rights standards, contravening a June 2007 Supreme Court judgment directing the government to enact legislation that would criminalize enforced disappearance in line with international standards. After the session of parliament was closed, the UCPN-M government in February 2009 passed the bill as an ordinance.

Despite strong condemnation from national and international organizations, the then government went ahead with the promulgation.[4] However, amid the political crisis, the ordinance was not endorsed by the next session of parliament and it lapsed. At this writing, a new draft of the bill is on the verge of being presented again to parliament. A group of national and international human rights organizations have issued a strong joint appeal to bring the bill fully in line with international standards.[5]

The organizations proposed a number of amendments to the draft of the bill, including:

- Defining “enforced disappearance” consistent with the internationally recognized definition and in recognition that, under some circumstances, the act of enforced disappearance amounts to a crime against humanity;

- Defining individual criminal liability, including responsibility of superiors and subordinates, consistent with internationally accepted legal standards;

- Establishing minimum and maximum penalties for the crime of enforced disappearance, and for enforced disappearance as a crime against humanity;

- Ensuring the independence, impartiality, and competence of the Commission;

- Ensuring that the Commission is granted the powers and means to effectively fulfil its mandate;

- Ensuring that all aspects of the Commission’s work respect, protect, and promote the rights of victims, witnesses, and alleged perpetrators;

- Ensuring that the recommendations of the Commission are made public and implemented.

An important aspect of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) of November 2006 was a promise to create a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) to, in the words of the document, “investigate those accused of serious violations of human rights and crimes against humanity during the course of the armed conflict and develop an atmosphere for reconciliation in the society.”[6]

Some TRCs have been helpful in acknowledging the grievances of those affected by conflict or repression. So long as such a commission is viewed as a complement to justice efforts, not a substitute for them, and does not lead to amnesties for serious human rights abusers, it could assist the peace process in Nepal. Many of the extrajudicial and other unlawful killings and disappearances listed in this report are largely unexplained, leaving the families of victims yearning not only for justice or reparations, but for truth and, ultimately, reconciliation. The creation of a TRC could be an important step in this process. Unfortunately, the current parliament has been almost totally paralyzed since it came into being after the April 2008 elections and has not considered many legislative initiatives.

In the absence of independent bodies such as a Disappearances Commission or a TRC which would normally make recommendations for compensation and other forms of reparation to the victims, some reparation initiatives are underway. However these are informal and decisions to award compensation are being made without law or standards to guide them.

Under the Common Minimum Program of the Maoist-led government, a decision was made by the government to compensate, “victims of conflict and those who suffered during the People’s Movement, People’s War and Madheshi agitation.”[7] As a result, a process has been put in place where people can make applications solely based on a reference from their Village Development Committee. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) like Advocacy Forum have assisted victims and their families to receive the interim relief of NRs100,000 (US$1,307) provided by the government to conflict victims. NGOs help victims by drafting applications, getting their case registered in the District Administration Offices (DAOs), and opening bank accounts. However, reports from Advocacy Forum staff and other non-governmental sources in some of the districts, especially Bardiya, show that the disbursement of the interim relief has not been impartial. These reports suggest that most of the victims receiving the money have been members of influential political parties. On several occasions, Advocacy Forum expressed its reservations that governmental reparation policies and schemes of economic assistance and relief for conflict victims would not be comprehensive. Furthermore, as highlighted in the “Update on Pending Cases” chapter of this report, some families are not proceeding with litigation fearing that it may affect their requests for compensation under this scheme.

The National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) is mandated to investigate alleged violations of human rights.[8] However, it has repeatedly expressed concern about the lack of implementation of its recommendations by successive governments.[9] At this writing, the Commission is awaiting information on whether its recommendations have been implemented and in particular, whether compensation it recommended has been provided.[10]

There is a need for appropriate and fair mechanisms to identify who is entitled to reparation and ensure there is no political manipulation or duplication. The lack of clarity is confusing families and is stopping them from taking further legal action, as explained above. Others continue to wait for the government to pay compensation recommended by the NHRC and are confused about whether or not the compensation they applied for and/or received from the government will jeopardize this.[11]

Despite the lack of accountability as a result of police investigations and the government’s failure to provide adequate compensation, relatives of victims are continuing to file FIRs. In the last year, another 16 FIRs have been filed, bringing the total number of FIRs filed with the help of Advocacy Forum so far to 65 concerning 77 cases.

Extrajudicial executions by the police and APF continue, especially in the southern Terai region where there is continuing political unrest in the ethnic minority Madeshi[12] community, with a rise in crime and villagers taking the law into their own hands.[13] Once again, the relatives of the victims are facing familiar obstacles: police are refusing to file FIRs, police are not taking bodies for post-mortem examinations and, when they are, the hospitals are not providing families access to post-mortem reports.

Unless and until Nepal’s political leadership puts in place and implements a comprehensive plan to address impunity, including prosecution of those responsible for crimes and compensation for affected families, victims and their relatives will continue to wait for justice.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch conducted the original research into the 62 cases highlighted in this report in October 2007 with the assistance of Advocacy Forum. Advocacy Forum provides legal assistance to many of the victims in these cases and has continued to monitor cases, visit police stations and courts, review files, and conduct interviews with victims and their families. Lawyers and staff based in the respective districts have met with the victims many times. They conducted dozens of interviews with families in Baglung, Banke, Dhading, Kanchanpur, Kaski, Kavre, Morang, Tanahun, and Udayapur districts in September 2009. Interviews were conducted with the full consent of the interviewees and as far as possible in private. Interviewees were informed of the purpose of the interviews and provided information on a voluntary basis. At no time did the interviewers offer or promise compensation.

Human Rights Watch sought the views of the Nepal Army by sending a letter by mail, fax, and email to Jag. Brigadier General Nirendra Prasad Aryal on August 3, 2009, seeking information about the outcome of internal army investigations into the cases. (See Appendix II). The head of the army’s Human Rights Directorate had promised to provide such information during a meeting at army headquarters with Human Rights Watch in September 2008. Human Rights Watch sent the fax again on August 6, and a staff member confirmed delivery. At this writing, we have received no reply.

Political Developments

Since the publication of Waiting for Justice in September 2008, there has been little or no progress in the peace process. The main obstacles are ongoing disputes over the implementation of key provisions in the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) of November 2006, and an increasing lack of trust between the main political actors. This lack of political progress has had direct impact on the human rights situation and the climate of impunity.

Disputes over implementation of the CPA center on the question of the integration and rehabilitation of 19,602 Maoist fighters verified by the United Nations Mission in Nepal (UNMIN), who have been held in cantonment sites around the country for nearly three years. The Nepal Army and many politicians in the Nepali Congress and other parties maintain that former Maoist combatants should be integrated into society.[14] The Unified Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) (UCPN-M) on the other hand holds the position that the integration agreed to in the CPA refers to integration of Maoist combatants into the security forces.[15]

In mid-July 2009 there was some progress when the Government of Nepal and the UCPN-M finally launched the discharge and rehabilitation process for 4,008 Maoist combatants, including 2,973 minors, whom the UN had found to have been recruited past an agreed cut-off date and/or to have been minors in 2007.[16] However, this process subsequently stalled amid further political instability.

There were increasing levels of mistrust between the UCPN-M and the other political parties as well as between the UCPN-M and the Nepal Army, not only relating to the question of integration but on wider security sector reform, including bringing the Nepal Army under effective civilian control.

This culminated in the resignation of Maoist Prime Minister Pushpa Kumar Dahal (alias Prachanda) in early May 2009 after President Dr Ram Bharan Yadav countermanded a decision by the cabinet to sack the Commander of the Army, General Katuwal. The Prime Minister had accused General Katuwal of insubordination.[17] The ensuing political as well as constitutional crisis lingers with a lack of clarity about the powers of the president under the Interim Constitution.

On May 5, 2009, the crisis deepened when local media leaked a video recording of a speech that Prachanda had made in January 2008 at a cantonment site in Chitwan, during which he said that the party had inflated the number of its army personnel presented for registration and verification. He also said that some money allocated for the cantonments would be used to “prepare for a revolt.” Despite later attempts by Prachanda to explain the context of the statement, it drew wide public condemnation and raised serious doubts about the Maoists’ commitment to the peace process among national and international observers.[18]

Madhav Kumar Nepal of the Communist Party of Nepal–United Marxist Leninist (CPN-UML), the party which had won 103 of 575 seats during the April 2008 elections, and who himself had lost the elections in two constituencies, was appointed as the new prime minister on May 23, 2009, with the support of a 22-party coalition. Intense negotiations over the allocation of portfolios and the government’s program dragged on for weeks, with intra- and inter-party tensions emerging. The main Madhesi party, the Madheshi People’s Rights Forum, split as a result of these disputes.[19]

Lack of cooperation between the political parties also severely impacted on the Constituent Assembly (which also functions as the parliament). Parties from across the political spectrum on numerous occasions have boycotted sessions contributing to delays in drafting a new constitution, as well as in passing new laws (including one to establish a Commission of Inquiry into Disappearances, as mandated by the CPA). There is growing concern that the deadline of May 2010 for the promulgation of the new Constitution (as stipulated in the Interim Constitution) cannot be met.

After leaving the government in May 2009, the UCPN-M expanded its protests to the streets, declaring bandhs (strikes) calling for “civilian supremacy” over the Nepal Army. Other organizations and political groups took their protests to the streets as they saw the political climate deteriorating and the promise of a “new Nepal”—so prominent during the Jana Andolan of April 2006—not materializing. Prominent among them were members of the Tharu and the Limbu communities, two of the largest Janajati (indigenous groups) in Nepal. Others, including the Nepali Congress and CPN-UML parties, armed Madhesi and other political groups in the southern Terai region, transporters and traders as well as local people organized a total of more than 600 bandhs in the first six months of the year.[20] This high level of disruption had a major impact on the country’s economy, which in addition was hit by a drop in remissions from Nepali migrant workers in the wake of the global economic crisis.

There was no tangible improvement in the human rights situation. Amid continuing concern about a deteriorating law and order situation, the cabinet on July 27, 2009 approved a “Special Security Program.” According to Home Minister Bhim Rawal, the security strategy includes plans to curb organised crime, a special security plan for Kathmandu valley, strengthening of the security situation in the Terai and the eastern and the mid-western hills, and raising public awareness to ensure effective implementation of the strategy.[21]

In 2009 there was a spate of killings of leaders and members of Madhesi armed groups by the Nepal Police and APF, which the authorities described as “encounter” killings. Advocacy Forum is investigating 14 cases of suspected extrajudicial executions between February and July 2009, four of which occurred in four days in July.[22]

The Nepal Police as well as the APF also continue to use torture during interrogation.[23] Furthermore, there are some worrying allegations of illegal detention and torture in private residences by the Nepal Police.[24]

Following the resignation of Prime Minister Prachanda, reported incidents of violence, threats, and intimidation by Maoists increased against individuals affiliated with other political parties, as did local inter-party tensions.[25] As with the incidents during the conflict, there is a complete lack of accountability for these more recent abuses.

Violent activities by armed groups belonging to ethnic communities in several parts of the country, especially in the southern Terai region, continue to take their toll on the civilian population. Incidents of abduction, intimidation, and extortion by these groups as well as by criminal gangs continue unchecked. Several incidents of mob violence by civilians and lynching criminal suspects to death or burning them alive have been reported.[26] This often extreme vigilantism can in part be attributed to failures of justice.[27]

Weaknesses of the main institutions of the criminal justice system—the Nepal Police and Attorney General’s Department—already identified in Waiting for Justice, are yet to be addressed. In May 2009, the new Chief Justice Min Bahadur Rayamajhi introduced some encouraging reforms, including on the establishment of a Court Decisions Enforcement Directorate, the setting up of a telephone hotline service for persons who wish to register complaints about irregularities in the judicial system and the installation of CCTV in the Supreme Court so as to avoid corruption and enhance transparency.

Though the name suggests that the Enforcement Directorate would seek to enforce decisions, it has been restricted to mere monitoring of whether or not decisions are implemented. There was also a detailed judgment by the Supreme Court in May 2009 ordering the government to criminalize torture, but it is yet to be implemented,[28] much like the landmark June 2007 judgment ordering the government to criminalize “disappearances.” The decisions have not been followed by reforms to the lower judiciary, which continues to perform poorly when handling mandamus petitions and other aspects of cases alleging serious human rights violations such as torture and “disappearance.”

The NHRC’s recommendations to the government are rarely implemented, despite repeated calls from civil society and the NHRC itself. In its annual report 2007-2008, the NHRC cited this government inaction as one of the major challenges to its work.[29] On June 26, 2009, it submitted a 10-point memorandum to the new prime minister to express concern about ongoing human rights violations. It also drew the prime minister’s attention to the lack of implementation of NHRC recommendations by successive governments.[30] On August 12, 2009, the NHRC stated it was encouraged to hear that the prime minister had instructed the Home, Defense, and Peace and Reconstruction Ministries to provide information on the implementation of NHRC's recommendations and had asked the ministries to send information on the recommendations implemented and compensation provided.[31] It remains to be seen whether this will result in the compensation recommended by the NHRC being awarded any time soon.

The UN’s role has come under fire from political actors, the media and civil society. They have questioned the role of UNMIN in the registration and verification of Maoist army personnel following the controversial video recording of Prachanda’s claims described earlier. This follows earlier criticism after Maoist soldiers abducted businessman Ram Hari Shrestha in April, 2008 and took him to the cantonment in Chitwan District, where he was tortured. He later died as a result of his injuries.[32]

The NHRC has continued to criticize the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in Nepal (OHCHR-Nepal). Members of the NHRC have repeatedly lobbied against the extension of the OHCHR-Nepal mandate. Amid the political crisis, the new government of Madhav Kumar Nepal, in June 2009, initially extended the OHCHR-Nepal mandate by only three months. This was later changed to a one-year extension. Civil society has criticized both OHCHR-Nepal and the NHRC for the lack of success in addressing impunity.[33]

Amid considerable political instability, the promises in the peace agreement of greater respect for human rights and accountability have not been delivered on and impunity remains firmly entrenched. Ending impunity for past and continuing violations and strengthening the criminal justice system are essential if Nepal is to continue to move away from violence and more firmly establish the rule of law. Unfortunately, politicians seem more interested in making empty pledges than addressing truth, justice, and reparations and tackling the lack of public security and rule of law, with all the political consequences that entails.

Update on Pending Cases

This section provides an update on the 62 cases—all alleging grave human rights violations—described in Waiting for Justice. Each case starts with a brief descriptor of the case, drawn from the “Summary of Testimony from FIR” in the appendix of Waiting for Justice. The update section then goes on to describe developments over the last year.[34]

Case 1:

Name: Raju B.K.

District: Baglung

On March 1, 2002, soldiers arrested Raju B.K. at his father’s house in Baglung Municipality-11. On March 4, a soldier contacted his family and brought them to the District Police Office (DPO), where the relatives were informed that Raju was killed while trying to escape. Raju had been shot twice on the left side of his chest and sustained injuries on his neck and forehead. The army pressured the family into cremating the body as soon as possible, and soldiers were present while the family conducted the funeral. Raju’s father tried to file a FIR, and, when no investigation of the incident took place, later appealed to the CDO, Prime Minister, and the NHRC. The Baglung DPO finally filed an FIR on March 18, 2007.

Update: On June 18, 2009, Raju’s family filed a petition of mandamus at the Baglung Appellate Court seeking an order for the police to promptly investigate the FIR filed in March 2007 and file charges to initiate prosecution of the alleged perpetrators. The DPO and public prosecutor sought to have the petition rejected, informing the court that “charge sheets can be filed only if investigations find evidence,” and that filing of charges is a decision of the Attorney General’s Office. However, Raju’s relatives believe that the police never really attempted to investigate and secure evidence. Advocacy Forum lawyers have been unable to find any evidence of progress in the police files. A final hearing was scheduled for September 7, 2009 but it was cancelled because the court was closed for Civil Servant Day. The next hearing is scheduled for October 14, 2009.

Case 2 and 3:

Name: Ganga Gauchan and Pahalbir BK (Pahal Singh)

District: Baglung

On July 11, 2004, four soldiers from Khadgadal Barracks beat Ganga Gauchan and Pahalbir BK in Tara VDC-5, in Sagukot. According to several witnesses, the soldiers then shot and killed them. Families of the two victims were threatened by members of the army and forced to dispose of the bodies immediately. Both families complained to the District Administration Office and the police, but no investigation was conducted. Police finally filed a FIR on February 15, 2007.

Update: On June 18, 2009, the victims' families filed separate petitions of mandamus with the Baglung Appellate Court. The authorities once again opposed the petitions, claiming that there was no evidence to merit filing charges and that in any case the Attorney General’s Office had to make the decision. A final hearing was scheduled for September 7, 2009 but it was cancelled because the court was closed for Civil Servant Day. The next hearing is scheduled for October 14, 2009.

Case 4:

Name: Dilli Prasad Sapkota

District: Baglung

A large group of security personnel arrested Dilli Prasad Sapkota on February 8, 2005, at Danbisaula, Pala VDC-9, in Baglung District. According to eyewitnesses, Dilli was tied to a tree, severely tortured, and finally shot dead. His family complained to Baglung DPO, but instead of registering the complaint, police officers threatened to kill the family. The Baglung DPO finally promised to file an FIR in 2006, but continued to delay the registration.

Update: As of August 2009, the FIR has still not been filed. The family has stated that they have lost hope and are no longer pursuing the case.

Case 5 and 6:

Name: Dal Bahadur Thapa and Parbati Thapa

District: Banke

A large group of security forces opened fire upon Dal Bahadur Thapa and his wife Parbati of Madanchowk, Banke District, on September 10, 2002. According to Dal’s mother, the officers forced the family to leave the house, stole money and personal property, and planted bombs. The next morning, security forces returned and retrieved the planted bombs. They then claimed that there was a clash with terrorists and that Dal and Parbati had been killed in the exchange of fire. Dal’s mother tried to register complaints with the army, the Armed Police Force (APF), the DAO, and the Banke DPO, but she was spurned and threatened at each institution. Police finally registered a FIR on July 15, 2007, after the Nepalgunj Appellate Court ordered the Banke DPO to do so. The police started investigations in May 2008, but the officers implicated in the complaint failed to respond.

Update: On April 16, 2009, the Area Police Office in Kohalpur sent a reminder, as a follow up to its May 5, 2008 letter to the Bageshwori Battalion of the APF, asking it to produce the suspects. On May 9, 2009, the Area Police Office informed Advocacy Forum representatives that there had been no response to the reminder.

On June 18, 2009, Dal’s mother filed a petition of mandamus at the Nepalgunj Appellate Court seeking an order for the police to promptly start an investigation into the FIR and to file charges against the alleged perpetrators.

Giving priority to this case, the Appellate Court scheduled a hearing on June 19, 2009. During the hearing, the judges asked why the mandamus petition had been delayed. They also referred briefly to the Maina Sunuwar case, wondering how effective a court order would be, if and when it was issued. The court ordered a “show cause” order for the Kohalpur APO, the DPO, and the public prosecutor to respond within 15 days. As of mid-September 2009, the court had not received their responses.

Case 7 and 8:

Name: Dhaniram Chaudhari and Jorilal Chaudhari

District: Banke

On September 29, 2004, during APF operations in Premnagar village of Khaskusma VDC ward no. 4, according to witnesses, security personnel detained brothers Dhaniram and Jorilal Chaudhari, and then shot them while in custody. When the victims’ wives tried to recover the bodies, security personnel threatened them. Relatives repeatedly tried to complain to the Banke DPO and CDO, but were ignored. After much resistance, police finally registered a FIR on October 29, 2007. Upon further pressure, the Kohalpur Area Police Office wrote to both the army and APF on May 5, 2008, but no responses were received.

Update:Relatives filed a petition of mandamus seeking an immediate police investigation and the filing of charges against those responsible.

As of mid-September 2009, the court had not received responses from police to notices issued by the court.

Case 9:

Name: Keshar Bahadur Basnet

District: Bardiya

On March 11, 2002, Keshar Bahadur Basnet was beaten by soldiers at his office in Bhurigaun, Banke District, and then arrested. According to Keshar’s elder brother, Dip Bahadur Basnet, and others who witnessed his arrest, Keshar was taken to the Thakurdhwara Army Barracks, but his family was refused access to him.

Another detainee told his relatives that he saw Keshar being driven away after over a month in illegal detention on April 16, 2002. He was accompanied by seven or eight soldiers. The Home Ministry later reported Keshar was killed in an armed encounter on April 11, 2002. The Bardiya DPO, after initial resistance, registered an FIR on February 14, 2007. The DPO contacted the Barakhadal Battalion (stationed at Thakurdhwara Army Barracks at the time) and asked them to respond to the allegations made in the FIR.

Update: On June 18, 2009, a petition of mandamus was filed at the Nepalgunj Appellate Court by the victim's family seeking a police investigation into the case.

Soon after the mandamus petition was filed before the Appellate Court and after a meeting between local politicians and the CDO where the police promised to investigate the case, the DPO Bardiya sent letters to three witnesses named in the FIR. Those people appeared at the DPO and gave their statements. After the court received replies from the respondents, a hearing was scheduled for September 13, 2009 but it could not take place as the court ran out of time.

Case 10:

Name: Bhauna Tharu (Bhauna Chaudhary)

District: Bardiya

According to witnesses, who were mostly Bhauna’s family members, on May 30, 2002, two soldiers shot Bhauna Tharu dead in his home in Sujanpur village, Neulapur VDC-4, in Bardiya District. Bhauna’s family recognized one of the soldiers. But when Bhauna’s father initially approached the Bardiya CDO, the officer rejected his complaint. A month later, two men attempted to bribe Bhauna’s father to sign a document stating that his son was a Maoist, but he refused. Bhauna’s father continued to approach the office of the CDO. On July 24, 2006, the Bardiya DPO registered an FIR after being ordered by the CDO to do so. The DPO attempted to contact the Thakurdhwara Army barracks for information about the suspects, but the army did not respond.

Update: On June 18, 2009, a petition of mandamus was filed at the Nepalgunj Appellate Court by the victim's family. The court issued a “show cause notice.”

Around the time the court gave this order, the DPO Bardiya sent letters to the witnesses specified in the FIR. Those people appeared at the DPO and gave their statements.

After the court received replies from the respondents, a hearing was scheduled for September 13, 2009 but it could not take place as the court ran out of time.

Case 11 and 12:

Name: Nar Bahadur Budhamagar and Ratan Bahadur Budhamagar

District: Dadeldhura

Soldiers picked up two brothers, Nar Bahadur and Ratan Bahadur, from their house in Jogmudha VDC-4, Gajalidanda, Dadeldhura District, on August 17, 2004 and, according to witnesses, later shot them dead, not far from their home. Two of the soldiers took Ratan’s wife to a nearby cowshed and raped her repeatedly. They also detained another brother, Man Bahadur Budhamagar, keeping him in illegal custody and torturing him for 17 days until he signed a statement saying that the soldiers did not rape his sister-in-law. When the family went to the Kanchanpur DPO to complain, the DPO refused to register their complaint. The DPO finally registered a FIR on June 18, 2007, after Advocacy Forum lawyers threatened to file for contempt of court as the police were not acting on an April 9, 2007 order from the Mahendranagar Appellate Court.

Update: Relatives filed a second mandamus, as well as a contempt of court petition, on June 5, 2008, because the police were not proceeding with investigations. In response to an order issued by the Kanchanpur Appellate Court on June 8, 2008, the DPO replied that it was conducting an investigation to identify the perpetrators. Police also informed the court that a preliminary report had been forwarded to the public prosecutor. The court therefore quashed the contempt of court petition on February 8, 2009. We have no information on what the public prosecutor has done since receiving the report.

Case 13:

Name: Jaya Lal Dhami

District: Dadeldhura

On February 12, 2005, security forces killed Jaya Lal Dhami at Putalibazaar. Villagers later reported that soldiers marched Jaya Lal and three others to the scene and executed them. Jaya Lal’s uncle contacted the Bhagatpur army barracks, who told him that Jaya Lal had been “accidentally” killed in a confrontation with alleged terrorists. The family went to the DPO and, later, the CDO to register the case, but both refused. Finally, on September 10, 2007, the police filed an FIR. As far as Advocacy Forum is aware the police did not follow up with investigations.

Update: On June 18, 2009, the family filed a petition of mandamus at the Kanchanpur Appellate Court, seeking a court order for police to promptly investigate the FIR. The court issued a “show cause” notice on June 21, 2009 requiring the respondents to inform the court within 7 days of any reason, if any, why the writ must not be issued. The respondents replied that the investigation was ongoing and there was no need to issue a writ petition. The court quashed the petition of mandamus on August 23, 2009 stating that the FIR has already been filed and the investigation is going on.

Case 14:

Name: Sarala Sapkota

District: Dhading

Soldiers arrested 15-year-old Sarala Sapkota on July 15, 2004 from her grandfather’s house in Chhapagaun, Dhading District. However, when her relatives went to Baireni Barracks and the Dhading DPO, the officers denied that the arrest had taken place. For 16 months, the family received no information on Sarala’s whereabouts. On January 11, 2006, an NHRC team uncovered her remains near her village. In June 2006, the police finally registered a FIR, but there was no progress in the investigation. In November 2007, the father filed a mandamus petition in the Supreme Court.

Update: Supreme Court hearings on the mandamus application scheduled for January 5, 2009, and June 22, 2009, were both postponed because the court did not have time to conduct them. The next hearing which was scheduled for August 16, 2009, could not take place for the same reason. The next hearing is scheduled for January 25, 2010. Thus, a petition seeking a prompt police investigation has gone unheard by the court for more than a year.

Case 15, 16, 17, 18, and 19:

Name: Sanjeev Kumar Karna, Durgesh Kumar Labh, Jitendra Jha, Shailendra Yadav, and Pramod Narayan Mandal

District: Dhanusha

Security forces arrested 11 people including the five above-named victims in the Kataiyachauri area of Janakpur Municipality-4, on October 8, 2003, and took them to the Regional Police Office in Janakpur. The next day, their families complained to the NHRC, which initiated an investigation. There was no news of the arrested men until more than two years later, when the NHRC received a letter from the Nepal Army Human Rights Cell stating that the five men had been killed in a “police operation.” On July 9, 2006, the families attempted to file two FIRs with the Dhanusha DPO, but the police informed them that it would not act on any conflict-related FIRs. In July 2006, witnesses showed police the site where the bodies of the men were believed to be buried. The fathers of Sanjeev Kumar Karna and Pramod Narayan Mandal filed a mandamus petition in the Supreme Court in January 2007.

Update: Although it is now three years since witnesses identified the site, Advocacy Forum lawyers have been unable to find any evidence of steps being taken to exhume the remains.

In response to the Supreme Court, the DPO initially argued that a FIR had not been registered in Diary No. 10 (the register for FIRs), and therefore there was no need to act on it. The Supreme Court, in its final hearing on the petition on February 3, 2009, issued a writ for the police to register the FIR and proceed with investigations. The FIR was subsequently registered. In its judgement, the Supreme Court noted the conflicting versions provided by the army and the police. An internal police investigation report states that the students were handed over to the Bhiman Barracks. The army on the other hand informed the court that the police were responsible for the disappearances and killing.

On January 29, 2008, the NHRC wrote a letter to the prime minister and Council of Ministers recommending that the government provide NRs300,000 (US$3,922) compensation to the families and initiate further investigations with a view to bring those responsible to justice.

Case 20 and 21:

Name: Ram Chandra Lal Karna and Manoj Kumar Dutta

District: Dhanusha

Security forces arrested Ram Chandra Lal Karna and Manoj Kumar Dutta on October 12, 2003, and beat Manoj severely. They were then taken to the Dhanusha DPO. Relatives went to several police stations and organizations but did not receive responses to their complaints. The men “disappeared.”

Two years later, on June 7, 2005, the Human Rights Cell of the Nepal Army informed the NHRC that the two men had been killed in an armed encounter. The families filed two FIRs on October 19, 2006. In January 2008, the Dhanusha DPO informed Advocacy Forum that it would not act on any conflict-related FIRs.

Update: On June 18, 2009, the relatives of Manoj Kumar and Ram Chandra Lal filed separate petitions at the Janakpur Appellate Court, seeking orders for the police to promptly start investigations into the FIRs registered in October 2006. On June 19, the court issued a “show cause” order seeking a reply within 15 days specifying the reasons, if any, why a writ of mandamus should not be issued. After the court received replies from the respondents, a hearing has been scheduled for November 10, 2009.

Case 22, 23, 24, 25 and 26:

Name: Lapten Yadav,Ram Nath Yadav, Shatrughan Yadav, Rajgir Yadav, and Ram Pukar Yadav

District: Dhanusha

Security personnel arrested these five men at their homes in Chorakoyalpul VDC-2, Dhanusha, early in the morning of October 1, 2004. According to eyewitnesses, they were first beaten and later, around 5 a.m., security forces shot and killed them in Chaurikhet, south of Keutani village, in Chorakoyalpur VDC. People dressed in civilian clothing but claiming to be security forces later informed the families that the men had been killed because of false information identifying them to be Maoists. On May 13, 2005, the NHRC started an investigation into the incident and recommended that the families be paid NRs150,000 (US$1,961) each as compensation. Five FIRs were filed in October 2007, but the Dhanusha police reiterated their policy of not acting on conflict-related FIRs.

Update: Advocacy Forum lawyers have been unable to find any evidence of progress in the police files. Despite the recommendation of the NHRC, as of August, 2009, compensation had not been paid. The families have not sought a writ of mandamus fearing that they would then be deprived of the compensation proposed by the NHRC. Their separate application for compensation under the Council of Ministers decision to compensate “conflict victims” has been successful. They all received R100,000 (US$1,307) as interim relief.

Case 27:

Name: Ramadevi Adhikari

District: Jhapa

Security forces arrested Ramadevi Adhikari and her husband at their home in Kalimati, Jhapa District, on July 3, 2005. Security forces accused her of giving food to Maoists. Later, Ramadevi was shot and killed. The security forces did not allow the body to be sent for an autopsy. When Ramadevi’s family approached the DPO and DAO to complain, they were spurned on the grounds that it was a “political case.” On November 9, 2006, the Jhapa DPO finally accepted a FIR filed by the relatives, and promised to register it. However, it was not registered.

Update: On April 22, 2009, the victim's husband tried to register the FIR at the DPO Jhapa. Despite the presence of many human rights organizations, the superintendent of police (SP), Bijay Kumar Bhatta, refused to register it.

Bhatta studied the FIR once and gave three reasons for not registering the complaint. He said that there was no autopsy report, that the FIR was being filed too late, and that the police and army were implicated in the complaint. SP Bhatta returned the FIR and told the victim's husband and Advocacy Forum lawyers to seek a court order to file the FIR, which he claimed he would then obey. On June 18, 2009, a petition of mandamus was filed at the Ilam Appellate Court seeking an order for the Jhapa DPO and SP Bhatta to register the FIR. A hearing scheduled on August 11, 2009 could not take place because one of the judges was absent. The hearing was rescheduled for October 12, 2009.

Case 28:

Name: Hari Prasad Bolakhe

District: Kavre

Police arrested Hari Prasad on December 27, 2003, at a bus stop in Phulbhari VDC-8, Kavre District. When his father went to the Kavre DPO to complain, the police denied having arrested him. After searching for months, his father complained to the NHRC, which investigated the case and discovered that Hari Prasad had been killed. The investigation led to the exhumation of Hari Prasad’s body, and medical testing of the body revealed the cause of death to be “gunfire injury to the pelvis.” The DPO in Kavre initially refused to register a FIR, and subsequently refused the CDO’s order to accept the complaint, saying that the senior army personnel implicated in the case were still working in the district. The Supreme Court in November 2006 ordered the DPO to register the complaint and to submit the case dossier.

Update: On February 2 and April 28, 2009, the Kavre DPO informed Advocacy Forum lawyers that the original case file had been forwarded to the Supreme Court and Advocacy Forum lawyers are unaware of any further progress in the investigation. Months later, however, the Supreme Court still has not heard the case or issued a writ of mandamus. The next hearing before the Supreme Court is scheduled for November 9, 2009.

Case 29:

Name: Reena Rasaili

District: Kavre

On February 12, 2004, armed soldiers raped and killed 18-year-old Reena Rasaili at her family’s home in Pokharichauri VDC-4, Kavre District. The family heard three gunshots and found her body lying near the house with bullet injuries in the head, eye, and chest. The family’s initial complaints to the DPO and CDO were ignored. A March 2004 NHRC investigation concluded that Reena had been illegally killed, recommending a payment of NRs150,000 (US$1,961) in compensation. It also recommended further investigations with a view to bring the perpetrators to justice. A FIR was finally registered on May 25, 2006. The police have received information from the army confirming that the squad of soldiers had been under the command of Saroj Basnet.[35] An application to the Supreme Court for a writ compelling the investigation was filed in October 2007.

Update: The Kavre DPO informed Advocacy Forum lawyers that the original case file had been forwarded to the Supreme Court, and Advocacy Forum lawyers have been unable to find any evidence of progress in the police files.

A Supreme Court hearing scheduled for April 13, 2009 was postponed to August 31, 2009. On August 31, 2009, the court issued an order to the DPO to forward details of investigations conducted so far. The court also allocated priority for the next hearing of the case: once the court receives an answer from the DPO, the case will be put first or second in the list of cases to be heard.

As of September 2009, there had been no action to implement the NHRC recommendations.

Case 30:

Name: Subhadra Chaulagain

District: Kavre

Soldiers shot and killed 17-year-old Subhadra Chaulagain at her home in Pokharichauri VDC-3, in Kavre District, accusing her of being a Maoist, according to her family who witnessed it. They beat her father severely. When Subhadra’s father made continuous appeals to the DPO, they threatened him with “further action.” The father then brought the case to the NHRC, which recommended a payment of NRs150,000 (US$1,961) in compensation and for those responsible for her killing to be brought to justice. A FIR was registered on June 6, 2006, but the police did not carry out any significant investigation. The family filed a case in the Supreme Court seeking an order against the authorities in Kavre in October 2007.

Update: The Kavre DPO informed Advocacy Forum lawyers that the original case file had been forwarded to the Supreme Court and there was no further progress in the investigation.

A Supreme Court hearing was scheduled on April 13, 2009 but the court ran out of time. At the next hearing on August 31, 2009, the court issued an order to the DPO to forward the details of investigations conducted so far. The court also allocated priority for the next hearing of the case: once the court receives an answer from the DPO, the case will be put first or second in the list of cases to be heard.

No compensation had been paid as of September 2009.

Case 31:

Name: Maina Sunuwar

District: Kavre

Soldiers picked up 15-year-old Maina Sunuwar on the morning of February 17, 2004 from her home in Kharelthok VDC-6 in Kavre District. When her friends and relatives went to the Lamidanda barracks the following day and demanded her release, the army denied having arrested her. After weeks of intensive campaigning, in April 2004, the army told Maina’s mother Devi that her daughter had been killed. Under pressure from the international community, the army prosecuted three of the perpetrators in a military court. Although convicted, they were sentenced to only a six months in prison which they did not serve as they were judged to have already spent that time while confined to barracks during the investigation.

Maina’s body was exhumed from inside the Panchkal Army Barracks in March 2007. The Supreme Court later responded to petitions by Maina’s family by ordering the Kavre DPO to initiate investigations. On February 3, 2008, the public prosecutor charged the three soldiers identified in the internal army proceedings (Bobi Khatri, Sunil Prasad Adhikari, and Amit Pun), and a fourth one identified by witnesses, Niranjan Basnet, with the illegal detention, torture, and the murder of Maina Sunuwar.

Update: As per the District Court’s orders, subpoenas were served to the defendants' addresses between March and July 2008, requiring them to appear at court within 70 days. Niranjan Basnet could not be served his subpoena because of a missing signature on the document. A hearing scheduled for December 16, 2008 was postponed due to lack of time, and postponed subsequently due to a general strike in Kavre District.

The hearing rescheduled for February 3, 2009, could not take place because the court clerk provided conflicting information to the public prosecutor and Devi's lawyer about the date.

On February 15, 2009, the court reissued a subpoena to Niranjan Basnet which was duly served on April 27, 2009. The court did not issue any other orders regarding evidence or witnesses for several months. Finally, in a significant ruling on September 13, 2009, the District Court ordered Nepal Army Headquarters to immediately proceed with the automatic suspension of Major Niranjan Basnet (one of the four accused believed to be still serving) and for Army Headquarters to submit all the files containing the statements of the people interviewed by the Military Court of Inquiry.

Case 32:

Name: Arjun Bahadur Lama

District: Kavre

Maoists abducted Arjun Bahadur, a secondary school management committee president, on April 19, 2005 from his school in Chhatrebanjh VDC, in Kavre District. According to witnesses, the men reportedly marched Arjun Bahadur through several villages before killing him. Following protests by his wife, the CPN-M claimed that Arjun was killed during a Nepal Army aerial strike. An NHRC investigation concluded Arjun had been detained and deliberately killed. Police in Kavre initially refused to investigate, fearing Maoist reprisals, but eventually responded to a Supreme Court order and filed a FIR on August 11, 2008. Among the six Maoists mentioned as perpetrators in the FIR is Agni Sapkota, a Central Committee member, originally from Sindhupalchowk District, on whose orders Arjun Bahadur Lama was allegedly killed.

Update: On February 4, 2009, Kavre police told Advocacy Forum they had corresponded with the Sindhupalchowk DPO on June 19, 2008, to search for and arrest defendants from that district. The police said that they received a letter from Sindhupalchowk DPO on July 25, stating that Agni Sapkota had not been found in their district. Agni Sapkota is now a member of the Constituent Assembly.

On April 28, 2009, Kavre police told Advocacy Forum, OHCHR-Nepal, and a member of the victim’s family they had taken no further action, but after two hours of dialogue they agreed to write a letter to NHRC requesting help to locate the exact place of burial of Arjun Lama and try to identify witnesses, with technical support from OHCHR if required.

The police questioned some witnesses in May, 2009. On May 4, 2009, the Kavre DPO wrote to the local police post at Foksingtar (the place where the killing allegedly took place) asking them to prepare a report about the incident.

Case 33 and 34:

Name: Chot Nath Ghimire and Shekhar Nath Ghimire

District: Lamjung

Soldiers detained Chot Nath Ghimire, a resident of Ishaneshwor VDC-4, Ratmate Majhpokhari, Lamjung District, on February 2, 2002 at Bhorletar Unified Command Base Camp. His cousin, Shekhar Nath, was summoned to the camp on February 7, 2002 and also detained. The police and army, however, denied their detention for years. But acting on information from other detainees, Chota Nath’s family found out that he had been detained at Bhorletar army camp and in November 2006 the NHRC were able to exhume Chot Nath’s body in the jungle at Saura in Hansapur VDC-9. Shekhar Nath’s body was found buried about 20 meters away. The Kaski DPO registered a FIR on November 19, 2006.

Update: As of August 2009, the Kaski DPO had not taken any action on the FIR.

On June 18, 2009, Chot Nath's and Shekhar Nath's families filed separate petitions of mandamus at the Kaski Appellate Court seeking orders for the Kaski DPO and Public Prosecutor’s Office to promptly investigate the FIR. On June 19, the appellate court issued “show cause” orders asking for reasons why the mandamus should not be issued within 15 days. On September 13, the court finally received answers from the respondents. The next hearing is scheduled for October 28, 2009.

The NHRC regional office in Pokhara has informed the family that its investigation into the killing of Chot Nath Ghimire and Shekhar Nath Ghimire is almost completed.

Case 35:

Name: Prem Bahadur Susling Magar

District: Morang

Security forces arrested Prem Bahadur Susling Magar, an affiliate of the CPN-M, at Aaitabare VDC, Morang District, on June 29, 2002, and allegedly killed him the next day. His family found out about his death via radio reports and located his body, decomposing in the street, a few days later. Their complaints to the Morang DPO five years later were disregarded by the police superintendent.

Update: The police have not formally registered the FIR. According to officials in the DAO, the copy of the FIR submitted to the CDO has gone missing. The family is considering filing a mandamus petition. The family has recently received NRs100,000 (US$1,307) through the DAO following the August 2008 decision of the Council of Ministers.

Case 36:

Name: Data Ram Timsina

District: Morang

On September 28, 2003, officers of the Eastern Regional Army Headquarters in Itahari, and security personnel from Morang DPO arrested schoolteacher Data Ram Timsina. The Morang DPO later informed his family that he was being detained at the Eastern Division Army Headquarters, and an eyewitness saw Data Ram being beaten and removed from the headquarters, and heard that he was to be killed. The Human Rights Cell of the NA later confirmed that Data Ram was “killed in a security operation at Kerabari VDC-5, in Morang District, on October 14, 2003.” The Morang DPO and CDO refused to register the case claiming they had “no authority.” The Biratnagar Appellate Court quashed a mandamus petition on the grounds that killings such as that of Data Ram will be investigated by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC).

Update: An appeal against the decision of the Appellate Court is pending before the Supreme Court. The next hearing is scheduled for September 17, 2009.

Case 37, 38 and 39:

Name: Bishwanath Parajuli, Tom Nath Poudel, and Dhan Bahadur Tamang

District: Morang

A group of 50 security personnel arrested Tom Nath Poudel, Bishwanath Parajuli, and Dhan Bahadur Tamang at Bhategauda, of Hasandaha VDC-8, in Morang District, on September 27, 2004. They accused the men of being Maoists and detained them overnight at a nearby school. Other individuals detained at the school later reported hearing gunshots at around 4:45 a.m. that night. The victims’ families visited the school and found that the men had been shot and killed. The families lodged a FIR application with the DAO on November 1, 2004, but no action was taken. An NHRC investigation found they were extrajudicial killings, and recommended the payment of NRs150,000 (US$1,961) and action against those responsible. The Morang DPO and CDO continued to refuse to register an FIR claiming they had no authority to do so. Dhan Bahadur’s family subsequently filed a mandamus petition at the Biratnagar Appellate Court. On October 10, 2007, the court ordered the DPO and CDO to register the FIR, but the DPO and CDO continued to refuse to register the FIR.

Update: On October 15, 2008, all the victims’ families attempted to file FIRs referring to the Appellate Court decision of October 2007, but only the FIR relating to the killing of Dhan Bahadur Tamang was accepted and filed the same day. There is no evidence of police initiating any investigations. On June 18, 2009, Dhan Bahadur Tamang's family filed a petition of mandamus at the Biratnagar Appellate Court seeking an order for the police to promptly start an investigation into the FIR. On June 19, the Appellate Court issued “show cause” orders asking for reasons why mandamus should not be issued. A hearing scheduled for August 10, 2009 was postponed as the court had not received any responses from police. The court has since received a reply from the respondents and the next hearing is scheduled for October 26, 2009.

The FIRs regarding the killings of Bishwanath and Tom Nath are still before the DPO. They have not been formally registered. The families are considering filing a mandamus petition but are awaiting the outcome of other mandamus petitions.

The compensation recommended by the NHRC has not yet been paid.

Case 40, 41, 42 and 43:

Name: Jag Prasad Rai, Dhananjaya Giri, Madhuram Gautam, and Ratna Bahadur Karki

District: Morang

According to witnesses, on December 18, 2004 security forces arrested and killed these four men in four separate incidents in Morang District. The Area Police Office in Urlabari notified the victims’ families of the deaths. Relatives found evidence of beatings and torture on the bodies. Their belongings were missing. Police initially refused to register the families’ complaints, claiming that it was a “political issue.” Later, the families attempted to secure justice again, but on June 5, 2007, the DPO in Morang again refused to register a FIR. Despite an appellate court writ compelling an investigation in the case of Madhuram Gautam, the superintendent of police, Yogendra Katuwal, continued to refuse to register the FIR. The court quashed the petition in the three other cases, agreeing with the police’s argument that the TRC will investigate them.

Update: On October 15, 2008, the victims’ families once again attempted to file FIRs. Police only accepted the FIR relating to the case of Madhuram Gautam, where there was a court order.

On June 18, 2009, Madhuram Gautam’s family filed a petition of mandamus at the Biratnagar Appellate Court seeking an order for the police to promptly start an investigation into the FIR. On June 19, the Appellate Court issued show cause orders asking for reasons why mandamus should not be issued. A hearing scheduled for August 10, 2009 was postponed as the court had not received any responses. The court has since received a response from the respondent and the next hearing is scheduled for October 21, 2009.

In the case of Dhananjaya Giri, the family has lodged an appeal against the decision of the Appellate Court to quash the case. The appeal is pending before the Supreme Court.

The FIRs regarding the killings of Jag Prasad Rai and Ratna Bahadur Karki have been before the Chief District Officer, but Advocacy Forum lawyers have been unable to find any evidence that action has been taken. Their families have not filed mandamus petitions to date because they want to see the outcome in other cases.

All families have recently received money from the CDO office as per the August 2008 decision of the Council of Ministers.

Case 44:

Name: Chandra Bahadur Basnet (“Manoj Basnet”)

District: Morang

On August 24, 2005, a group of APF personnel arrested Chandra Bahadur Basnet at Dhankute Hotel, in Biratnagar. They put him in a vehicle blindfolded, and drove away. The next day, the Morang DPO informed Manoj’s family that he had been killed while trying to run away from a “security cordon.” His body, with all valuables removed, was handed over to his family in Biratnagar the next day. A post-mortem revealed that he had been shot in the chest and neck.

As a result of NHRC and OHCHR investigations, the APF claimed to have taken action against Nardip Basnet (the commander of the APF unit allegedly involved in the killing). But the action apparently was merely transferring him out of the district.

Under considerable pressure, the DPO in Morang filed a FIR on August 30, 2005 and agreed to initiate an investigation. The police then got Chandra’s father to sign a new FIR terming the killing an accident without allowing him the time to read it in detail. The District Court agreed with this FIR, ruling that the killing was accidental. Chandra’s father then appealed to the Supreme Court. After this, a number of local political actors and police officers attempted to bribe the father with large sums of money and job offers. On November 30, 2007, he acceded to this pressure and asked the court to withdraw the case. On the same day, the Supreme Court decided to put the case on hold.

Update: In response to the father’s request to the Supreme Court to withdraw the case, Advocacy Forum filed a petition to resume the hearing claiming that it was a public interest issue. A judicial bench of Kalyan Shrestha and Krishna Upadhyay quashed the petition on May 4, 2009, bringing the case to an end.

Case 45 and 46:

Name: Purna Shrestha and Bidur Bhattarai

District: Morang

According to witnesses, army personnel tricked Purna Shrestha and Bidur Bhattarai into coming to Belbari VDC on October 15, 2005 by calling them from the mobile phone belonging to one of their friends. They then arrested both men, tortured them, and shot them dead at around 9:30 am. The army then informed family members that the men had been killed during an army operation. The families and other villagers found torture-related wounds on the bodies although they were not able to obtain copies of the post-mortem reports.

The NHRC recommended a compensation of NRs150,000 (US$1,961) each and said that those responsible should be identified and brought to justice. The government is yet to act on these recommendations. During June and July of 2007, the Morang DPO and CDO both refused to register a FIR. The Appellate Court in Biratnagar refused a petition on behalf of Bidur, but ordered the DPO to register a FIR in the case of Purna. Police Superintendent Yogendra Katuwal refused to register the FIR.

Update: On October 15, 2008, the victims’ families once again attempted to file FIRs. Police only accepted the FIR relating to Purna Shrestha. On June 18, 2009, Purna Shrestha's family filed a petition of mandamus at the Biratnagar Appellate Court seeking an order for the police to promptly start an investigation into the FIR. The court issued a “show cause” notice on June 19, 2009. A hearing was scheduled for August 10, 2009. As of mid-September 2009, the court had not yet received replies from the respondents.

In the case of Bidur Bhattarai, the family has appealed to the Supreme Court against the decision of the Appellate Court. The case is pending before the Supreme Court.

Case 47:

Name: Sapana Gurung

District: Morang

15 security personnel under the command of army Captain Prahlad Thapa Magar arrested 22-year-old Sapana Gurung at her home in Belbari VDC-3, Morang District, on April 25, 2006. The men took her to a nearby Nepal Telecommunications Office and raped her. About an hour after the arrest, villagers heard a gunshot, and Sapana was later found dead. A medical report stated that she had been raped and killed. The police quickly registered a FIR, but waited for governmental authorization before investigating. A Parliamentary Probe Committee recommended that Prahlad Thapa Magar, Bir Bahadur Mahara, and Nirmal Kumar Panta be taken into custody and that a criminal investigation be initiated. The Committee also recommended NRs 1 million (US$13,070) compensation for the family and departmental action against those responsible under the Army Act. The government earlier had paid NRs300,000 (US$3,922) to the family.

Update: Advocacy Forum lawyers have been unable to find any evidence of progress in the police investigations. The police claim that the file has not been returned by the Parliamentary Probe Committee. As of August 2009, the soldiers had not been arrested. There were unconfirmed reports that the army had brought the three soldiers before a military court. The compensation recommended by the Parliamentary Committee has not been paid.

Case 48, 49, 50, 51, 5 and 53:

Name: Chhatra Bahadur Pariyar, Phurwa Sherpa, Prabhunath Bhattarai, Prasad Gurung, Tanka Lal Chaudhari, and Sunita Risidev

District: Morang

On April 26, 2006 a group of security personnel opened fire on people demonstrating against the killing of Sapana Gurung (described above) outside the area police office in Belbari. The six individuals named above were killed, and dozens were injured. The Morang DPO initially refused to file FIRs. When the Belbari area police filed FIRs, they argued that they could not initiate criminal investigations until the government had authorized such action. A Parliamentary Probe Committee recommended action against 28 security force personnel (including the head of the brigade and the chief of Belbari police), and the CDO. It also recommended NRs 1 million (US$13,070) each to the families of those killed and smaller amounts for those injured. Earlier, the government had already provided NRs300,000 (US$3,922) to the families of those killed, and smaller amounts for those injured.

Update: Advocacy Forum lawyers have been unable to find any evidence of progress in the police investigations. The police claim that the file has not been returned by the Parliamentary Probe Committee.

Case 54:

Name: Khagendra Buddhathoki

District: Myagdi