Irom Chanu Sharmila may be a world record-holder, but nobody is celebrating her milestone. She recently began her tenth year of a hunger strike -- more than 3,000 days. She can share credit for this unhappy achievement with the Indian government, whose abuses Sharmila was protesting when she was detained, and which keeps her alive against her will.

Sharmila began her hunger strike in November 2000, after security forces killed 10 people by indiscriminately firing into a crowd in the northeastern Indian state of Manipur, on the border with Burma, which has witnessed an armed separatist battle for almost five decades. She has survived because government doctors force-feed her through a pipe stuffed into her nose.

The authorities in Manipur keep her in judicial custody to prevent her from committing suicide. Frail after all these years of fasting, she isn't able to talk much anymore. But when I visited her some time back, she whispered her belief that in the land of Mohandas Gandhi, a peaceful hunger strike would draw attention to military crimes.

Sharmila has a single demand: repeal the Armed Forces Special Powers Act. Enacted as an emergency law over 50 years ago, the legislation gives India's armed forces unchecked powers to search, arrest and use lethal force. The military claims that it is deployed to contain internal armed conflict situations only when it becomes too violent for the police to handle, and thus they need special powers to operate. In effect, however, the law has been widely abused, resulting in deaths due to indiscriminate firing and numerous cases of arbitrary detention. Unfortunately, soldiers responsible for these acts get away with it because the law also provides immunity from prosecution for acts committed in the so-called course of duty.

The act was designed to be an emergency measure but, after decades of being in force, has instead resulted in a much more violent society. Since the army is not held accountable, the police, government officials and even militants believe they have the same privilege and commit crimes without fear of punishment.

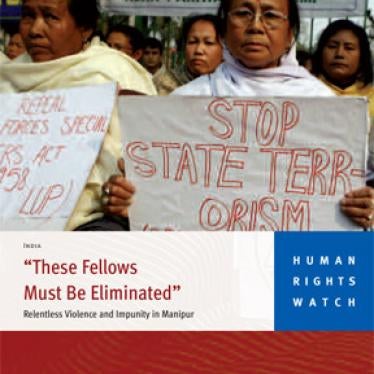

Sharmila is not the only one who has tried to shame the government into action. In one of the most shocking form of popular protest India has ever seen, in 2004 a group of elderly women stripped naked in front of the paramilitary Assam Rifles headquarters in Manipur, protesting the rape and murder of a Manipuri woman by some soldiers. One of the protesters later explained to me: "We shed our clothes and stood before the army. We said, ‘We mothers have come. Drink our blood. Eat our flesh. Maybe this way you can spare our daughters.'"

Photos of women driven to such a desperate act shocked the country and forced the government's hand. It set up a review committee, which soon recommended repeal of the Special Powers Act because it had become "a symbol of oppression, an object of hate and an instrument of discrimination and high handedness."

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh promised to punish those responsible, review the law, and "work together with the people of Manipur to write a new chapter" in the state's history. But in the face of resistance from the army, the government has failed to implement the recommendations of its own hand-picked committee.

As for Sharmila, with a painful tube constantly hanging over her face, she seeks solace from holy texts. And sometimes she writes letters to Indian leaders. In one note, she asked the ruling Congress Party's president, Sonia Gandhi, to intervene. Sharmila received no response. It is doubtful that India's politicians read her letters.

Though the Indian government ignored Sharmila's protest for years, the pressure is growing for a review of the Armed Forces Special Powers Act. Navi Pillay, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, recently joined the chorus recommending that India repeal such laws that "breach contemporary international human rights standards." The Indian parliament will soon debate the government's proposed amendments to the law. Yet the Singh government has not made its proposals public, nor published a draft law for public scrutiny and debate.

This is a critical moment for India. Its economy may be booming, but there is a darker side of violence and brutality in Indian society that the government must urgently address if it is to resolve the many regional conflicts that hold the country back becoming a genuinely modern international power.

As Sharmila begins the tenth year of her hunger strike, scores of individuals and human rights groups have been protesting in solidarity. Pressure from abroad has also helped to prompt the upcoming parliamentary review. Now is the time for bold action by the government. It shouldn't tinker around the edges with amendments, but repeal the law in full. For that to occur, however, the government may need a little more encouragement.

Meenakshi Ganguly is senior South Asia researcher at Human Rights Watch.