The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) sets out to eliminate all forms of discrimination against women and guarantee equality. In article 1 States commit to eradicate "any distinction, exclusion or restriction made on the basis of sex ... on a basis of equality of men and women, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural, civil or any other field."

UN treaty monitoring bodies, with a mandate authoritatively to interpret the treaties, have defined the scope of the term “sex” in the key covenants as encompassing sexual orientation. The Human Rights Committee decided in the 1994 case of Toonen v. Australia that “the reference to ‘sex’ in articles 2, paragraph 1, and 26 is to be taken as including sexual orientation.” The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights also included sexual orientation in its interpretation of article 2, paragraph 2, of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. It also included this interpretation in its year 2000 general comment No. 14 on the right to health (para. 18).

Article 2 of CEDAW condemns all forms of discrimination against women. States parties to the convention thus have committed to take specific steps and pursue all appropriate means to eliminate such discrimination. As the Committee considers a general recommendation interpreting Article 2, we consider it crucial to specify that sexual orientation and gender identity are prohibited bases for discrimination, and demand and deserve protection.

In Human Rights Watch's experience and research, as well as in the work of this Committee, two things in this regard are clear:

1) Discrimination against women takes many forms. In fact, many women encounter multiform and distinctive forms of discrimination due to the intersection of sex with such factors as race, language, ethnicity, culture, religion, disability, or socio-economic class. Indigenous women, minority women, migrant women, displaced women, and non-national women may experience distinctive discrimination because of the intersection of their sex and race, or their sex and citizenship status.

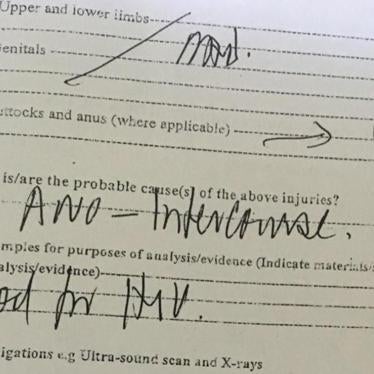

Women may also confront particular forms of gender discrimination based on how they deploy their sexualities or the way they express or identify themselves through their sexualities. These in turn may intersect with other forms of discrimination. Women living with HIV/AIDS may face additional stigma through the presumption that they practice prohibited sex and often fear the social and legal consequences of seeking treatment. Only a comprehensive understanding of the different grounds and forms of discrimination can help us construct effective measures of protection, remedy, and redress.

The Special Rapporteur on the Right to Housing recognized the intersectionality between discrimination and sexuality in a 2005 report to the Commission on Human Rights. It stated that “[a]n intersectional approach to gender discrimination is essential to address such multiple forms of discrimination faced by women.” The Special Rapporteur found that women face multiple forms of discrimination, including on the grounds of race, class, ethnicity, caste, health, disability, and other factors. In addition to these factors, he stated, “lesbian and transgender women may face violations of their right to adequate housing because of their marginalized status.”

To eliminate all forms of discrimination against women, as the Convention requires, specific measures are needed to address the ways in which women are differently affected in their enjoyment of a right as a result of the intersection of discrimination based on sex with discrimination based on other characteristics. Recognizing this basic fact should be prominent in the General Recommendation.

2) The systems and assumptions that cause discrimination against women are often invisible because they are deeply embedded in social relations, both public and private, within all States.

Article 5 of the Convention recognizes this in mandating states to "modify the social and cultural patterns of conduct of men and women, with a view to achieving the elimination of prejudices and customary and other practices which are based on the idea of the inferiority or the superiority of either of the sexes or on stereotyped roles for men and women." Acknowledging this systemic and entrenched discrimination is an essential step in implementing guarantees of non-discrimination and equality—and guaranteeing women’s autonomy and freedom—including their autonomy over their sexualities.

Moreover, policies to eliminate discrimination must be implemented in a manner that ensures to women the substantively equal exercise and enjoyment of their human rights, as protected in CEDAW and in other conventions. This enjoyment of rights cannot be achieved solely or simply by passing laws or promulgating policies that are gender-neutral on their face. Gender-neutral laws and policies can perpetuate sex inequality invisibly, because they do not take into account the special needs and historic disadvantage of women, in particular women from disadvantaged groups.

In consequence, the General Recommendation we are concerned with here should build on other recommendations, such as General Recommendation No. 25, in ways to ensure that de facto equality is guaranteed. De facto or substantive equality requires that States ensure that direct and indirect discrimination is abolished in the law and that protections are available against this discrimination; that States secure that all women benefit from concrete and effective policies and programs to improve their situation; and that States address the persistence of gender-based stereotypes that affect women. Governments should take these steps to provide equality for women in their material conditions, regardless of their status—including their sexual orientation.

Distinguished members of the CEDAW Committee:

Human Rights Watch has drawn heavily upon the Montreal Principles on Women’s Economic, Social and Cultural Rights for this statement. In doing so we hope to convey a concern not simply limited to women’s rights in the abstract. In fact, our research and experience tell us that how policymakers strive to eliminate discrimination against women—the terms, breadth, and scope of their measures—matters profoundly. Failure to be comprehensive and inclusive can have devastating consequences for women trying to live their lives in dignity.

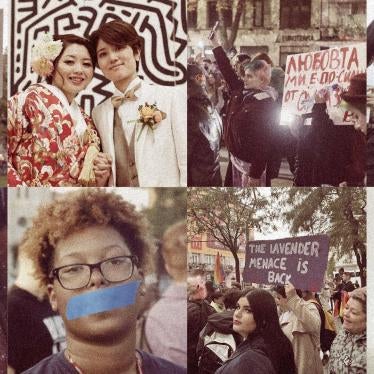

In countries like South Africa, where the law guarantees equality on all grounds, violence against women is still rampant. Lesbians have been targeted for rape and murder. In other words: law may guarantee equal protection against violence, but practice does not. The South African case is only one example, showing that States have an immediate obligation to address this violence and protect these women; in South Africa, the state still has not. All forms of discrimination need to be addressed for all women. Leaving some women out of protective measures is unacceptable. The General Recommendation should urge that States take immediate steps to end violence against women on the grounds of their sexual orientation and gender identity.

This Committee has recognized violence against women as a form of discrimination, most notably in its General Recommendation No. 19. The General Recommendation under study should complement the former by specifically mentioning sexual orientation or gender identity as examples of gender-based violence. The UN Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women recognizes that women may be subject to gender-based violence on the grounds of their ethnicity, sexual orientation, family, or other status. The Rapporteur has specifically noted that in many communities women who act in a manner “deemed to be sexually inappropriate by communal standards is liable to be punished” and that women who “live out their sexuality in ways other than heterosexuality are often subjected to violence and degrading treatment.”

Human Rights Watch continues to document ongoing discrimination against women in all aspects of their lives and identities, including sexual orientation and gender identity. We are happy to share this research experience with the Committee in detail. We know it shows the need for explicit protection against discrimination based on those grounds.

It is far from our desire—or any advocate’s—to promote a hierarchy of grounds of discrimination. Rather, we urge undoing the silent hierarchy that now exists, where certain inequalities remain hidden and unspoken. Despite the clarity of international law and legal protections in this regard, unless such protection is made explicit, a group of women is likely to be left unprotected.

Thus we recommend in developing its General Recommendation on Article 2 that the Committee:

1) Explicitly recognizes sexual orientation and gender identity as a basis for protection under Article 2. This approach will be consistent with how the CEDAW Committee and other treaty monitoring bodies have interpreted and uphold women’s rights to sexual autonomy.

2) Build on earlier general recommendations, including general recommendation No. 19 (eleventh session, 1992), on violence against women, and No. 25 (thirtieth session, 2004), on temporary special measures, by specifically mentioning sexual orientation and gender identity as grounds for protection.

New York—July 15, 2008