Incompetence, negligence, and irresponsibility by U.S. states put condemned prisoners at needless risk of excruciating pain during lethal injection executions, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today.

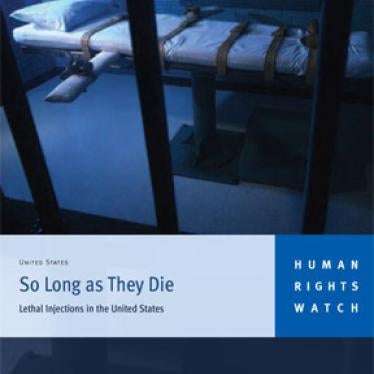

The 65-page report, “So Long as They Die: Lethal Injections in the United States,” reveals the slipshod history of executions by lethal injection, using a protocol created three decades ago with no scientific research, nor modern adaptation, and still unchanged today. As the prisoner lies strapped to a gurney, a series of three drugs is injected into his vein by executioners hidden behind a wall. A massive dose of sodium thiopental, an anesthetic, is injected first, followed by pancuronium bromide, which paralyzes voluntary muscles, but leaves the prisoner fully conscious and able to experience pain. A third drug, potassium chloride, quickly causes cardiac arrest, but the drug is so painful that veterinarian guidelines prohibit its use unless a veterinarian first ensures that the pet to be put down is deeply unconscious. No such precaution is taken for prisoners being executed.

“The U.S. takes more care killing dogs than people,” said Jamie Fellner, U.S. program director at Human Rights Watch and co-author of the report. “Just because a prisoner may have killed without care or conscience does not mean that the state should follow suit.”

Human Rights Watch opposes capital punishment in all circumstances and calls for its abolition. But until the 38 death penalty states and the federal government abolish capital punishment, international human rights law requires them to ensure they have developed a method of execution that will reduce, to the greatest extent possible, the condemned prisoner’s risk of mental or physical pain and suffering.

Human Rights Watch urges that states suspend execution by lethal injection until they have conducted a thorough review and assessment of existing and alternative methods.

The drug sequence used in the United States was developed in 1977 by a medical examiner in Oklahoma who had no expertise in pharmacology or anesthesia. Texas quickly adopted Oklahoma’s protocol, and at least 34 other states then did too. (Nevada’s protocol remains secret). Human Right Watch found that none of the states consulted medical experts to ascertain whether the original three-drug sequence could be adapted to lessen the risk of pain to the prisoner by using other drugs or methods of administering them.

“Copycatting is not the right way to decide how to put people to death,” said Fellner. “If a state is going to execute someone, it must do its homework, consult with experts, and select a method designed to inflict the least possible pain and suffering.”

Without adequate or properly-administered anesthesia, prisoners executed by the three-drug sequence would be conscious during suffocation caused by the paralytic agent, and would feel the fiery pain from the potassium chloride coursing through their veins. Logs from recent executions in California, and toxicology reports from recent executions in North Carolina, suggest prisoners may in fact have been inadequately anesthetized before being put to death.

Corrections agencies have rejected the option of executing prisoners with a single massive injection of a barbiturate, even though that should provide a painless death, because such a method would force executioners and witnesses to wait about 30 minutes longer for the prisoner’s heart to stop beating. Corrections officials have also resisted eliminating the pancuronium bromide – the paralytic agent – even though its use makes it much harder to tell if a prisoner is sufficiently anesthetized. The drug is not needed to kill the prisoner, nor does it protect him from pain: it appears intended mainly to keep his body from twitching or convulsing while dying. It also masks any pain the prisoner might be feeling, since he cannot move, cry out, or even blink his eyes.

“Prison officials have been more concerned about sparing the sensitivities of executioners and witnesses than protecting the condemned prisoner from pain,” said Fellner. “They are more concerned with appearances than with the reality.”

Although prisoners have for years brought legal claims that lethal injections were unconstitutionally cruel, courts have until recently given short shrift to their arguments. Troubled by new and powerful evidence of possibly botched executions, federal courts in California and North Carolina have this year refused to permit scheduled executions to take place using the standard lethal injection protocol. On April 26, the U.S. Supreme Court will hear oral arguments about the procedures a prisoner must follow to challenge lethal injections.

Until recent years, the United States was the only country in the world that used lethal injection as an execution method. Several other countries that have not yet abolished the death penalty have followed: China started using lethal injection in 1997; Guatemala executed its first prisoner by lethal injection in 1998; and the Philippines and Thailand have had lethal injection execution laws in place since 2001 (although to date, they have not executed anyone by this method).