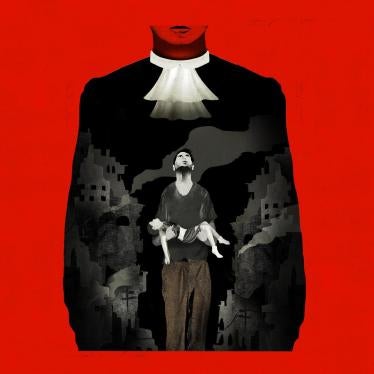

As Kosovo’s Albanians prepare for victory - full independence - in the status talks taking place between Belgrade and Pristina, the province’s fearful minorities are holding their breath, unsure who to trust and how all this will pan out after six years of waiting. If Belgrade agrees to sever ties with Kosovo, it is likely many will leave, unwilling or too afraid to give the Albanians and the international community the chance to make good on promises of their protection - promises that have been broken time and again.

The death of Slobodan Milosevic – whose stirring of Serb nationalism over Kosovo helped him rise to power – is unlikely to affect the status talks long-term. International negotiators are cautiously optimistic about brokering a deal that gives the Albanian majority independence, yet guarantees the protection of minorities, mostly Serbs and Roma, who account for 10 per cent of Kosovo’s population. Under U.N. rule, minorities have lived mostly in mono-ethnic enclaves, looking to Belgrade rather than the U.N. or Albanians for support and guidance in politics and in daily life.

The future of minorities – to live at peace in Kosovo or not - is at the heart of status talks. Ironically it was a series of anti-minority attacks two years ago this month that seems to have set the wheels of decision in motion after years of paralysis.

Over two dreadful days in March 2004, some 50,000 people took to the streets across Kosovo in violent riots. Kosovo’s minorities bore the brunt of the violence, which left close to two dozen dead and 1,000 injured. More than 4,000 people were displaced. Hundreds of minority homes and churches, monasteries, and public buildings were burned in arson attacks.

The violence of March 2004 has largely been forgotten. Attention has shifted to the complex negotiations on Kosovo’s international status, with Albanians holding out for independence from Belgrade and Serbs insisting on autonomy within the same boundaries. The conventional wisdom holds that March 2004 is a chapter of the past - something nasty, but taken care of.

In reality, the violence of those 48 hours is far from resolved. Without addressing its legacy - the usual cycle of impunity - Kosovo cannot move forward. The events of March 2004 were characterized as a wake-up call for the international community and to Kosovo’s Albanian leadership. March 2004 was a test of their will to bring criminals to justice and to progress towards real co-existence for Kosovo’s fractured communities.

The pledge was simple: March would be fixed. Ruined homes would be rebuilt, the displaced would be assisted, and those responsible for the violence would be brought to justice, reversing Kosovo’s miserable record on prosecuting inter-ethnic crime.

But two years on, there has been only limited progress in prosecuting those responsible. The special international police operation established to investigate was disbanded early last year for ineffectiveness. Around 450 individuals have been charged, but most with only minor offences. Only about half of the cases have been tried, and those that ended in convictions often produced lenient sentences.

Even in the 56 serious cases taken up by the international community, results are limited. Only 13 cases have been decided. An equal number have been dismissed. The rest are under investigation and nowhere near ready for trial.

The response on housing has been little better. While most destroyed homes have been reconstructed, they remain empty, because continuing harassment make most displaced minorities too frightened to go home. But even if they felt safe, returning would be difficult because of slipshod work. The standard of reconstruction has often been very poor. In some cases, the construction faults are so severe that independent engineers have assessed the rebuilt houses as “uninhabitable.”

The reconstruction project - budgeted at more than 10m Euros - has a long way to go before fulfilling its promise. But that money ran out, or was paid out, long before the job was done. This glaring gap on reconstruction and return only serves to reinforce the belief among many minorities that the international community and the majority ethnic Albanian leadership lack the will to address their concerns.

The inadequate response to inter-ethnic violence in March 2004 depicts in miniature two of the greatest problems facing Kosovo - how to end the rampant impunity for serious crime, and how to ensure that minority communities are able to live in safety and dignity. Without a functioning justice system, and equal protection for all, Kosovo cannot succeed, whatever the outcome of the status talks.