The government has an obligation to protect those who reside in the UK. It also has a duty to safeguard the country's fundamental values. We have seen little evidence that the current counter-terrorism strategy has made Britain a safer place. Yet it has eroded the ban on torture, undermined the principle of equality under the law and weakened the right to a fair trial. The Law Lords have a historic opportunity to restore the balance. All those who care about liberty must hope they seize it.

The government suspended core human rights in the wake of 9/11, allowing it to detain foreign nationals indefinitely without charge or trial. It says it is entitled to rely on evidence produced by torture elsewhere.

If the panel decides these changes are justified, a profound and dangerous shift will have taken place. The principle of equality under the law—a cornerstone of the legal system in democratic countries around the world—will have been abandoned. Worse still, the absolute ban on torture will have been seriously undermined.

The government has said that the power to detain foreign nationals indefinitely is justified because the UK faces a serious threat from terrorism.

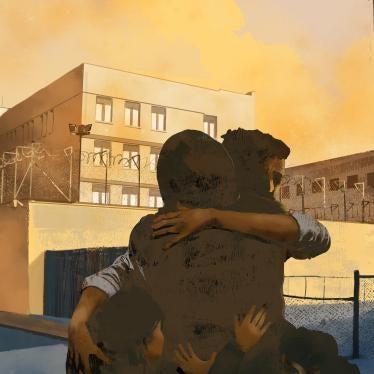

It also insists that the suspects detained, at Belmarsh prison in south-east London and elsewhere, are free to leave the country at any time. It says it abhors torture, but says it would “be irresponsible” to ignore information on terrorism from elsewhere, even if torture was used.

The threat from terrorism is real. But it does not justify the erosion of core human rights, in legal or in practical terms. The government believes it is entitled to remove basic legal rights from people merely because they hold a foreign passport. Yet most of those arrested on terrorism charges since 9/11 have been British citizens, who rightly continue to enjoy the traditional safeguards of the legal system: they must be charged and put on trial, or released.

The government argues that the detainees cannot be prosecuted under current laws. But those same constraints limit prosecutions against British terror suspects, too. The answer is to reform the law—by allowing judges more discretion in the use of phone tap evidence, say—so those who act against national security can be put on trial, Britons and non-Britons alike.

A ruling in favour of indefinite detention is unlikely to impress British Muslims, many of whom regard the detentions as an injustice targeted against their community. There is growing evidence that the government's policy alienates the very group whose cooperation the police and security services need most to combat terrorism.

The recent release of D, an Algerian detainee, does not mean the necessary safeguards are in place. On the contrary, it underscores the arbitrariness of the government's approach.

D still knows neither the case against him, nor why he has been freed. His reaction, on hearing that his long detention was about to end was: “I don't understand.” Lack of logic is a constant.

At Belmarsh—unlike at Guantánamo—many detainees are not even questioned, despite being held for more than two years. The Home Office believes this is “not extraordinary.”

The government's line on torture is even more pernicious. Torture is a universal taboo. There are no excuses or exceptions, and no government in the world will admit carrying it out.

Britain was key in drawing up international rules outlawing torture and a convention aimed at making them stick. Last August, the government successfully argued in the Court of Appeal that information gained under torture can be used if the UK is not involved directly.

The arguments for torture are superficially seductive. How, it is argued, can it be wrong to torture somebody who may have information that could save lives? Once the door to torture is open, however, experience suggests it is impossible to close. The message that it is sometimes acceptable undermines more than half a century of work to eradicate this moral cancer.

Concern is mounting about Britain's counter-terrorism strategy. The Privy Counsellor Review Committee called for the “urgent repeal” of the indefinite detention regime. The all-party parliamentary Joint Human Rights Committee pointed to the “corrosive effect” of the policy. Lord Justice Neuberger, who dissented from the appeal judgment, argued that by relying on torture evidence, Britain was “losing the moral high ground an open democratic society enjoys.”

The government has an obligation to protect those who reside in the UK. It also has a duty to safeguard the country's fundamental values. We have seen little evidence that the current counter-terrorism strategy has made Britain a safer place.

Yet it has eroded the ban on torture, undermined the principle of equality under the law and weakened the right to a fair trial. The Law Lords have a historic opportunity to restore the balance. All those who care about liberty must hope they seize it.