Mr. Bush now seems to recognize as well that it is not enough for the United States to be against terrorism. To succeed, he explained, Washington must also embrace a positive vision of "freedom," "liberty," and "democracy," especially in the Middle East. Yet this important message will fall flat if Mr. Bush does not move beyond stirring rhetoric and begin to live by these principles.

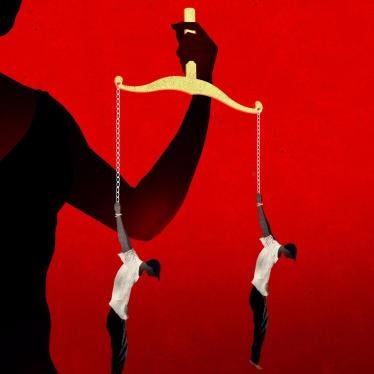

The truth is, American military might, imposing as it is, will never be enough to defeat terrorism. There are simply too many places for terrorists to operate below the radar screen. Terrorism will succumb only where peaceful political change is a realistic option, and people embrace the international human rights and humanitarian law that explain why terrorism is wrong.

Creating such societies is the goal of activists throughout the Middle East. Women's rights activists in Morocco recently sparked changes in the family-status law; Iranian parliamentarians are exposing judicial abuses; Saudi demonstrators are defending political prisoners and protesting government corruption. Their work needs international support.

Significantly, Mr. Bush acknowledged the counterproductive nature of past U.S. support for repressive Middle East regimes. But until future U.S. conduct is transformed, many people will continue to see Mr. Bush's promotion of democracy as hypocritical.

Mr. Bush broke new ground in identifying Egypt and Saudi Arabia by name as governments that must democratize, although his language was more hortatory than critical. And he reiterated familiar criticism of such long-time nemeses as Syria and Iran. But on Israel's treatment of Palestinians, the human-rights abuse about which Middle Easterners are most passionate, he was silent. He appropriately said that Palestinian leaders must reform, but said nothing about such attributes of Israel's occupation as assassinations and collective punishment. No American human-rights policy will be credible in Middle Eastern eyes without ending the Israel exception.

Mr. Bush also spoke tepidly about the rest of the Islamic world. He praised "democratic progress" in Indonesia but ignored Indonesian atrocities in Aceh -- currently the subject of a lawsuit in U.S. courts that the Bush administration is trying to dismiss. He made no mention of Pervez Musharraf's military rule in Pakistan or Islam Karimov's brutal dictatorship in Uzbekistan -- close U.S. allies in the war against terrorism.

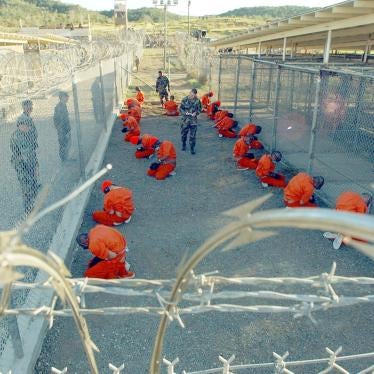

Nor did Mr. Bush offer any commitment to respect human rights in Washington's own conduct -- the legal black hole of Guantanamo, the denial of due process rights to "enemy combatants," proposed military commissions with no meaningful right of appeal, the use of "stress and duress" interrogation techniques, the misuse of immigration law, the rendering of suspects to countries such as Syria that practice torture, and the placement of suspects in secret detention facilities with no right to due process. These are the tools of a police state, not the methods of a champion of democracy.

When Mr. Reagan made his parliamentary speech, his commitment to democracy also seemed hypocritical, coming at a time of U.S. support for highly abusive forces in El Salvador, Nicaragua, Angola, Liberia, Somalia, and Zaire. But recognizing the need to walk the walk, not just talk the talk, Mr. Reagan began to offer actual U.S. support for local efforts to topple the dictatorships of Ferdinand Marcos in the Philippines, Jean-Claude Duvalier in Haiti, and Augusto Pinochet in Chile -- all, previously, U.S. allies.

Mr. Bush, too, should take this opportunity to bring U.S. behaviour into line with U.S. preaching. Only a genuine commitment to fighting terrorism in strict compliance with democracy, human rights, and the rule of law will make Mr. Bush's articulated vision credible and attractive in the places where it is needed most.