Eight years after the end of the war in Croatia, ethnic discrimination continues to impede the return of hundreds of thousands of Croatian Serbs displaced by the war, Human Rights Watch said in a new report released today.

in Croatian

PDF MS Word

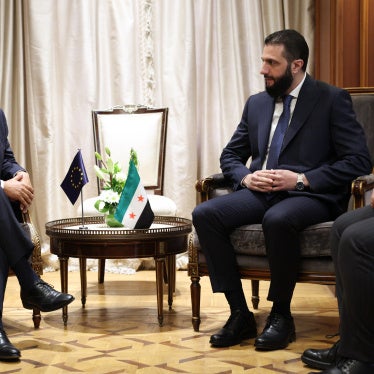

The 61-page report, “Broken Promises: Impediments to Refugee Return to Croatia," describes the plight of displaced Croatian Serbs and urges that progress on return be made a condition of Croatia’s application to join the European Union.

“The impediments to return are insurmountable,” said Lotte Leicht, Brussels office director of Human Rights Watch. “It is time that the government of Croatia starts being part of the solution rather than part of the problem.”

There are no precise statistics for how many of the more than 300,000 displaced Serbs have returned. The Croatian government has registered more than 100,000 returns, but many returnees, after a short stay in Croatia, depart again for Serbia and Montenegro or Bosnia and Herzegovina. In 1991 Serbs made up 12.1 percent of Croatia’s population, but the 2001 census showed their number had fallen to 4.5 percent.

Most of those who have returned have been elderly farmers whose houses were not destroyed or occupied, and who receive old-age pensions from the government. Return to urban areas is rare, because the refugees cannot repossess their pre-war apartments or obtain substitute housing. Young and middle-aged Croatian Serbs are dissuaded from returning by lack of employment opportunities and, for men, fear of arbitrary arrests on war crime charges.

These problems are a result of a practice of ethnic discrimination against Serbs by the Croatian government, Human Rights Watch said. The report contrasts the difficulties in return of Serbs with the government’s success in enabling the vast majority of ethnic Croats to return to their pre-war homes.

"The government has never genuinely tried to facilitate Serb return," said Leicht. "Instead, the authorities have consistently prioritized the needs and rights of ethnic Croats—including Croat refugees from Bosnia—over the rights of Serb refugees and returnees."

The Human Rights Watch report is based on two years of research involving a comprehensive review of local legislation and extensive interviews with returned refugees, temporary occupants of their houses, and representatives of Serb civic associations, national and local governmental bodies, international organizations, and Croatian human rights groups. The report includes recommendations to the Croatian government and the international community to facilitate the return of Serb refugees.

Personal accounts from “Broken Promises: Impediments to Refugee Return in Croatia”:

Ivan Kovac, a Bosnian-born Croat, lived as an immigrant in Australia until he came to Croatia in 1995. Since 1997, Kovac has run a restaurant in Gracac in a home owned by Danilo Stanic, a Serb. Stanic and his wife returned to Gracac in 1998, but the local housing commission ignored their repeated requests that the commission evict Kovac. In July 2002, pursuant to Stanic’s private lawsuit, Gracac municipal court ordered that Kovac vacate the part of the house used as a restaurant, but the restaurant continued operating as of June 2003, pending a court decision on Kovac’s appeal.

Boja Gajica (53), a Serb returnee to Knin, applied eight times between 1996 and 2000 for the position of nursing attendant, for which she has an associate degree. Each time a Croat candidate, with lower or different qualifications, was selected. On one occasion, the manager of a child-care center allegedly told Ms. Gajica that she would be afraid of the local soldiers and policemen if she employed a Serb.

In June 2002, Human Right Watch observed the court proceedings on repossession of property, in which the defendants—a Bosnian Croat wife and her Muslim husband, occupants of a three-story Serb house in Karlovac—explained that they opposed sharing the house temporarily with the owner because, in the husband’s words, “He cannot live with us. We were at war with such like him for four years.” The owner, Dusan Vilenica, returned to Karlovac in 1998 and has been unable to reoccupy the house or move into its uninhabited parts since.