One measure of America's importance is the frequency with which countries do outrageous things when they think Americans aren't watching. Saddam Hussein used to do his worst when official Washington was on vacation — his offensive into Iraqi Kurdistan during the final days of August 1996, for example. North Korea may have provoked a crisis now because it sensed the Bush administration was distracted by Iraq. And how better to explain Russia's recent decision to end the mission of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) to Chechnya?

And how better to explain Russia's recent decision to end the mission of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) to Chechnya? The OSCE mission was the world's eyes and ears on the ground in Chechnya — its only real mechanism for monitoring the war and promoting dialogue. Getting the OSCE monitors in was also the Bush administration's single concrete achievement on Chechnya, an agreement it extracted from Russian President Vladimir Putin before his first summit with President Bush in 2001. Now Putin has taken that one and only concession back, becoming just the third European leader — after Slobodan Milosevic and Belarus's dictator, Alexander Lukashenko — to try to kick an OSCE mission out of his country.

It's easy to guess what the opportunistic Russian leader is thinking: Surely the Americans are too preoccupied with Iraq — and with trying not to seem so preoccupied with Iraq that they can't also focus on Korea — to make an issue of anything else now. And sure enough, the administration's response has been as low-key as they come. U.S. diplomats quietly tried to change Russia's mind, then took no for an answer and moved on. Instead of winning concessions, the administration is granting them: Yesterday the State Department announced it would place three Chechen groups on its list of terrorist organizations — a decision that may be objectively justified but that Russia will see as a quid for its support on Iraq.

The message this sends — that the United States can focus only on one crisis now — won't be lost on Russia or other countries. When war in Iraq begins, look for Russia to push the envelope even further — perhaps by shutting down the remaining camps that shelter displaced Chechens and pushing them back to the war zone. If Putin thinks the United States won't notice, he's probably right.

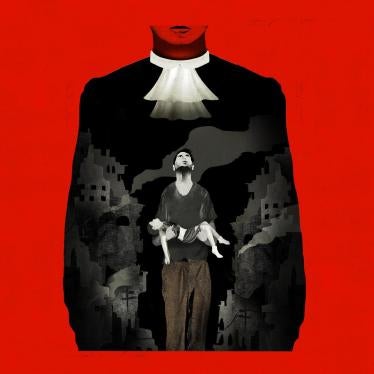

Why should we notice? It's not simply that the torture and disappearances committed by Russian forces in Chechnya bear such a sad resemblance to the atrocities that trouble President Bush when committed in Baghdad or Pyongyang. It is also because Russia has cast these cruelties as its contribution to America's fight against global terrorism. And it is because Russia's actions fan the flames they are meant to extinguish. They punish Chechens whether or not they participate in terrorism, offering no incentive to reject terror. They are forging a generation of young people who know only violence, making them easy recruits for those who preach only violence.

One reason little is said is that Chechnya breeds a sense of futility among American officials. They want to do more than react to bad news; they want to solve the problem, to find a comprehensive settlement. But this conflict appears to defy solution. Both sides kill civilians. Both seem locked in a mutual suicide pact of irrational behavior. So diplomats grow weary, then disgusted, then uninterested.

In the meantime, with a few exceptions (including the current U.S. ambassador to Moscow, Alexander Vershbow), American officials resist publicly criticizing the Russian abuses they despair of ending. Speaking out may "make us feel good," they say, but it does Chechen civilians no good. Russia, they argue, will carry on no matter what Americans say. So why antagonize a vital partner? Why provoke Putin into the fits of anger he routinely, deliberately and shrewdly throws when outsiders dare to confront him about Chechnya?

But if the Russian government truly doesn't care about what the United States thinks and says, why does it schedule its most provocative actions when America's attention is turned elsewhere? Why is it so intent on expelling the few outsiders who can tell Americans what is happening in Chechnya? Why does it go to such lengths to frame its actions with the language and imagery of America's struggle with terrorism? Of course American reactions matter to Russia. When Putin tried recently to use Bush's statements on preemption to justify an attack on Georgia, he backed off after the United States made clear its opposition.

The war in Chechnya may not end soon. But the mere fact that the United States and the world are paying attention to what both sides are doing, with energetic monitors on the ground and strong public statements from the top, can still minimize the war's harm. The Bush administration must show that it is neither too defeatist nor too distracted to try.