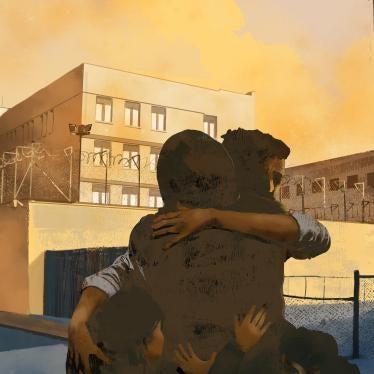

NEW YORK The Bush administration thinks it deserves congratulations for its recent decision to apply the Geneva conventions to some of its prisoners from Afghanistan. The decision appears to reverse public statements by Vice President Dick Cheney, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, and even President George W. Bush himself that the detainees in its Guantánamo Bay base in Cuba didn't merit protection under the laws of war. Rumsfeld last week outlined an uncertain future for the hundreds of prisoners of the Afghan war being held in Cuba, saying that they might be returned to their own countries or held indefinitely to prevent them from taking up arms again. The United States holds 300 men from 26 countries in captivity at the Guantánamo base, as well as 194 men in Afghanistan itself.

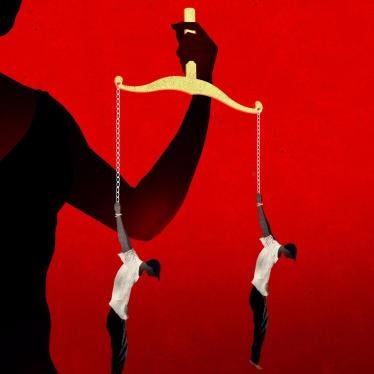

But the new policy of the Bush administration on the prisoners in Cuba is no more than smoke and mirrors. In fact, the White House is manipulating the conventions in selective and highly political ways: Bush has said that Taliban detainees will not be granted their prisoner-of-war rights under the conventions, and that Al Qaeda detainees won't be covered by the conventions at all.

Such flouting of the laws of war does more than threaten to violate the detainees' rights to suit the administration's preferences. It endangers American troops - and the armed forces of U.S. allies - who might some day find themselves captured in combat. To justify this shredding of a widely ratified treaty, the White House has tried to suggest that the Guantánamo detainees pose novel and difficult questions of international law. But its arguments don't hold up.

First, the White House says that the Third Geneva Convention on prisoners of war does not cover members of Al Qaeda because they are terrorists, not government troops. But the convention expressly applies to all combatants captured in the course of an international armed conflict, regardless of how they are characterized.

Second, the White House asserts that Taliban fighters, whom it does admit are covered by the convention, do not qualify for POW status because they allegedly failed to wear distinctive insignia and abide by the laws of war.

But the convention states that the members of the armed forces of an enemy government are automatically entitled to POW status.

By manufacturing this new test for government troops, Bush hands enemy forces a ready excuse for denying POW status to captured American and allied troops. One can easily imagine Saddam Hussein, for example, using the administration's argument to deny POW status to a captured American pilot by asserting that U.S. bombing violated the laws of war, or to deny POW status to captured American special forces who were operating undercover, without distinctive insignia. Using the administration's argument, India could cite Pakistan's alleged support for terrorism to deny its soldiers POW status. Syria could deny captured Israeli soldiers POW status by saying that they have attacked civilians in Lebanon. The Geneva conventions were designed precisely to avoid those kinds of subjective judgments by warring parties who hate each other.

Contrary to the administration's claims, granting POW status to Taliban fighters would not disrupt legitimate U.S. efforts to interrogate terrorist suspects.

Similarly, POW status prohibits prosecution only for lawful attacks on opposing military forces. Still permitted are prosecutions for war crimes or attacks on civilians, whether before or during the conflict. If a POW is prosecuted for such offenses, the duty to repatriate him at the end of hostilities would take effect only after any sentence had been served. So why is the administration refusing to apply the Geneva conventions' straightforward rules?

Probably to ensure that even the small number of Taliban detainees in Guantánamo can be tried by Bush's controversial military commissions. The convention entitles POWs to the same trial procedures as the detaining power would give its own service members facing similar charges - that is, a court-martial.

Maybe the administration is afraid its case wouldn't be strong enough to hold up before a court-martial. But that risks substituting vengeance for justice.

Apart from protecting POWs, the Geneva conventions also contain the most broadly accepted international prohibitions against waging war by attacking civilians - that is, terrorism. To suggest that certain causes justify setting the conventions aside is to accept the ends-justify-the-means logic of terrorism.

That is surely the Bush administration's most serious mistake of all.