One year after pro-Indonesia militias, backed by the Indonesian army, killed, burned and looted their way across East Timor in response to the August 30, 1999, referendum on independence, not a single perpetrator of those crimes has been brought to trial. If justice is to be done, the international community needs to be less naive about the Indonesian judicial system.

At the moment, Indonesia -- not East Timor, and not the United Nations -- holds the key to accountability for the grave crimes that took place. Key member states of the U.N. early on rejected the idea of an international tribunal on both political and logistical grounds. Asian countries were wary of setting a precedent for the international prosecution of human rights abuses in the region -- Russia had Chechnya and China had Tibet and Xinjiang to think about. Some Western countries were worried about alienating the Indonesian army and provoking a coup at a time when Indonesia's transition to democracy was still fragile. There was also concern about the costs of setting up an international tribunal and who would bear the expenses.

The U.N. Transitional Administration in East Timor, for its part, had to set up a court system from scratch. It designated a special international panel of the newly created Dili District Court and formally installed judges on July 20. But even if the panel has the structure and statutes in place to try serious crimes, it may not be able to get the serious criminals. Virtually all the masterminds of the violence are in Indonesia and still free. The likelihood they will be extradited to East Timor is low.

Unfortunately, so are East Timorese expectations of justice in Indonesia. The Indonesian government under former President B.J. Habibie lobbied hard against a special U.N. commission of inquiry into the violence in East Timor, arguing that Jakarta could undertake an investigation on its own. In the end, both the U.N. and the Indonesian inquiries went ahead.

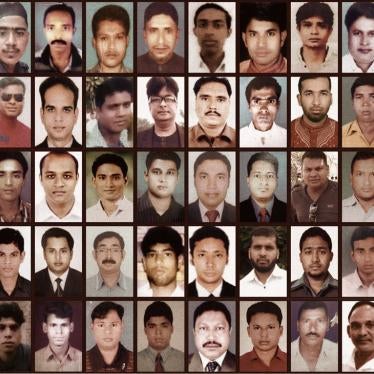

The U.N. commission concluded in its January report to U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan that the Indonesian army and militias were guilty of a pattern of gross human rights violations and breaches of humanitarian law in East Timor. That pattern included widespread and systematic intimidation, humiliation, terror, destruction of property, violence against women and displacement of people. Emphasizing that East Timor's future social and political stability depended on truth and reconciliation and the prosecution of those responsible for crimes, it recommended, among other things, that the U.N. establish an "international human rights tribunal consisting of judges appointed by the U.N., preferably with the participation of members from East Timor and Indonesia."

Much to its credit, the Indonesian government produced its own highly professional report that was harder-hitting than its international counterpart.

Two more developments kept alive the international community's faith in the Indonesian government's commitment to justice. First, the Indonesian investigation was turned over in January 2000 to Attorney-General Marzuki Darusman, the well-regarded former head of the Indonesian Human Rights Commission. The second was President Abdurrahman Wahid's dismissal in February of General Wiranto, the man who had been commander of the Indonesian military when the sacking of East Timor took place.

But General Wiranto's dismissal, while a triumph of civilian over military authority, hasn't led to prosecutions of army officers. And Mr. Marzuki appointed an investigative team made up of people not only from his office but also from two institutions linked directly to the 1999 violence: the police and the army. As counterweights, he appointed an advisory body of experts, including some highly credible human rights activists, but doubts about the quality of the team remain to this day.

However, the obstacles to justice go far deeper than the competence of the investigators. The fact is that Indonesian courts are notoriously corrupt, and even if Mr. Marzuki produces indictments, it is still unlikely anyone will actually be convicted. If competent and incorruptible judges could be found, there is no clear legal basis for prosecutions on anything except ordinary criminal charges.

A constitutional amendment passed last week by Indonesia's parliament, the People's Consultative Assembly, at the behest of the army, makes it all the more unlikely that anyone in Indonesia will face charges of war crimes or crimes against humanity. The constitution will now say no one can be indicted for crimes committed before the enactment of laws used to prosecute them. The assembly is currently debating legislation establishing a truth commission, but it includes a provision under which those responsible for gross human rights abuses could receive amnesty in exchange for information.

Even more fundamental is the lack of support from key institutions in Indonesia for pursuing East Timorese cases. During the past two months, the same militias who torched East Timor in September 1999 have been terrorizing refugee camps and international humanitarian workers in hit-and-run raids across the border from West Timor. Had there been any political will in the Indonesian government to do so, the militia leaders could have been stopped and disarmed months ago. If the government can't -- or won't -- even arrest known thugs for causing violence on Indonesian soil, who is going to believe in their will to track down and arrest those responsible for crimes in their former colony?

Following his trip to East Timor earlier this year, Secretary-General Annan promised he would "closely monitor progress" Indonesia makes in redressing the crimes its security forces committed in East Timor. It's time Mr. Annan and U.N. Security Council members set specific benchmarks for progress. Those should include a clear legal basis for an Indonesian court to indict and try suspected perpetrators and credible personnel appointed as judges, prosecutors and staff. The court should have clear jurisdiction over not only crimes already extant in Indonesia's Criminal Code, but also crimes subject to universal jurisdiction in international law, such as crimes against humanity. Finally, Indonesian authorities should establish a witness-protection program and stop granting amnesties.

If Indonesia can't meet these standards it should invite the U.N. to step in and set up a tribunal that can.

Joe Saunders is Deputy Asia Director at Human Rights Watch.