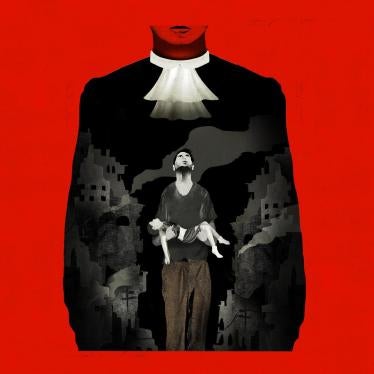

Human Rights Watch is writing with recommendations about the administration of justice for individuals implicated under Lebanese and international law for various acts during the Israeli occupation of south Lebanon.

The Military Court Trials

The trials that began in the military court on June 5 do not appear to be aimed at identifying and prosecuting Lebanese who committed the most serious offenses under international human rights and humanitarian law. Rather, the rapid pace at which the tribunal has been conducting the trials leaves little doubt that the goal is to prosecute and punish as quickly as possible, in summary proceedings, those who were taken into custody after the Israeli withdrawal. This diverse group includes former SLA combatants of various ranks, civilians who traveled to or worked in Israel or for the Israeli civil administration in south Lebanon, and individuals who provided information to Israeli intelligence operatives.

The court has been convening in lengthy sessions that typically commence at ten in the morning and end at about nine in the evening. The judges only have time to deliberate on cases between the daily recess in the afternoon, and after the trials conclude in the evening, with judgments handed down before or after midnight. The number of defendants has varied at each session. On June 23, for example, the court tried eighty-three defendants, whose sentences ranged from one week to five years imprisonment, in addition to banning many of them from returning to their communities for periods ranging from one year to seven years after release from prison. Nineteen were tried on July 9, while on July 14 the number increased to seventy.

A Human Rights Watch representative who attended five sessions of the military court in June observed that the time allotted to each defendant's trial ranged from a minimum of two minutes to a maximum of fifteen minutes, with the length determined by the complexity of the case and the seriousness of the charges. The presiding judge asked most defendants similar questions and would refer to information in their files that had been collected by military intelligence investigators while defendants were held incommunicado and had no access to lawyers. Civilians who visited Israel were asked when and why they traveled there, and, if relevant, were questioned further about the type of jobs they held and the dates of employment. Former employees of the civil administration were asked to describe their jobs, salary, length of service, and supervisors, and were also queried about their contacts with Israeli officers and information that they provided about individuals or suspicious movements to SLA or Israeli officers. Former militiamen were questioned about circumstances of their recruitment, dates of service, and salary, and were asked to describe where they served, the weapons they carried, and military operations in which they participated. They were also asked to provide the names of their immediate commanders and the soldiers who served with them, and describe information that they provided to SLA or Israeli officers about individuals or suspicious movements.

We observed that defense lawyers were not familiar with the case files, which they received the day before the proceedings. Some lawyers told us that the files did not necessarily include the complete record of their clients' interrogations and may have been abbreviated summaries. Although the court was willing to grant lawyers' requests for an adjournment of several weeks in order to study the files and prepare a proper legal defense, in most cases the lawyers did not ask for more time. They appeared resigned to the fact that the court was issuing formulaic judgments and sentences in the overwhelming majority of cases, and that more personalized defenses would have no effect on the court's rulings.

Following the questions of the presiding judge, there was rarely cross-examination of defendants by the military prosecutors or the defense lawyers. We also noted that lawyers typically opted for broad, standardized defenses rather than tailoring statements to the individual facts and evidence of the cases of their clients.

The abbreviated proceedings and speed that have been the main features of these trials since June 5 -- which have gone largely unchallenged by defense lawyers -- leaves the defendants without the rights ensured under article 14 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which Lebanon has ratified. These include the right "to have adequate time and facilities for the preparation of his defence and to communicate with counsel of his own choosing" (article 14/3/b) and the right "to examine, or have examined, the witnesses against him and to obtain the attendance and examination of witnesses on his behalf under the same conditions as witnesses against him" (article 14/3/e).

The military court has ignored the claims of some defendants that they were tortured or mistreated while in custody. According to the Foundation for Human and Humanitarian Rights in Lebanon (FHHRL), a nongovernmental organization that is monitoring the trials, these include: Hussein Zayn al-Abidin (June 21 trial); Zakaria Fadlallah Jum'a (June 26 trial); and Hanna Karim al-Alam (July 3 trial). FHHRL reported that al-Alam "claimed that he was tortured and pointed out to the court the pus and blood-stained bandages around his leg," and said that medical care was not provided for five days.

A last concern is that there is no independent judicial oversight of the military court. The U.N. Human Rights Committee noted this in April 1997, when it expressed concern about "the lack of supervision over the military court's procedures and verdicts by the ordinary courts."

Given these major shortcomings, Human Rights Watch recommends that those convicted in the military court be afforded the opportunity to seek a retrial before an independent and impartial civilian court with full due process guarantees, including effective legal representation and court procedures that allow time for the presentation of evidence and witnesses. Anyone convicted in a retrial also must be afforded the right to have the judgment and sentence reviewed by a higher tribunal in accordance with Lebanese law.

Formation of a Commission of Inquiry

The structure and scope of the ongoing trials in the military court do not provide a venue for eyewitnesses to or victims of violations of international human rights and humanitarian law to be heard. Human Rights Watch therefore urges the government to conduct thorough, independent and transparent investigations in order to identify Lebanese and Israelis suspected of committing such crimes during the occupation of south Lebanon. Particularly with respect to the gravity of alleged offenses that may constitute war crimes, the process used to identify suspects must be above reproach. For this reason we recommend that the government assign this responsibility to an independent commission of inquiry, especially in light of the substantial flaws noted above with respect to the military justice system.

Since the Israeli withdrawal, investigators from Lebanese military intelligence and investigating judges from the military court have questioned former SLA militiamen in advance of their trials. This process undoubtedly has yielded information about the command and control structure of the militia, and its direct and indirect links to Israeli military and intelligences forces. The files may also include testimony about Lebanese and Israeli perpetrators of crimes such as torture at Khiam detention center and local SLA security offices, expulsion of individuals and entire families from the zone, and forced conscription of men and children into the militia.

This information is likely to be tainted, however, because it was obtained while the detainees were held incommunicado and some of them reportedly were subjected to physical abuse. The complete interrogation and investigation files should nevertheless be provided to the commission of inquiry for the purpose of identifying eyewitnesses and others who may have knowledge of specific acts that violate international law. The commission should hear the testimony again under conditions that are not coercive and conform to international standards of witness deposition. From this starting point, evidence can be sought in a systematic manner.

The inquiry should not be restricted to information provided by former militiamen and others who have been or will be tried in the military court. It should extend to individual victims who can describe specific incidents or identify Lebanese and Israeli perpetrators. Research that Human Rights Watch has undertaken in south Lebanon indicates that residents there are able and willing to provide detailed and persuasive testimony about the perpetrators and circumstances of torture, forced conscription, and expulsion. Last month, residents of one village provided information about six former SLA militiamen who tortured or ordered the torture of civilians in their custody.

Suspects in Lebanon who are identified in the investigations of the commission of inquiry should not face the military judicial system but should be tried in civilian courts with all due process guarantees.

Suspects in Israel and Other Countries

Some suspects may include former SLA officers who were not active in the militia at the time of the withdrawal but left Lebanon and secured legal residence abroad in past years. Others may be among the thousands who fled Lebanon for Israel during the Israeli military withdrawal in May. It is widely expected that most of those who fled will be settled in Israel or leave for third countries. The Israeli daily newspaper Haaretz reported on June 2 that about 1,000 will leave Israel "in coming months to be given political asylum abroad" and that "countries in Europe and in North and South America have agreed to accept former [SLA] men and their families on humanitarian grounds." The newspaper also reported that "Israel will finance resettling the refugees abroad," and said that the effort is being coordinated by the Defense Directorate for Aid, a division of the Shin Bet, one of the Israeli intelligence agencies that was active in former occupied zone. According to a report in the Jerusalem Post on July 17, among the countries that may consider asylum for former militiamen are Canada, Chile, France, Germany, and the United States.

Under international law, every person has the right to seek asylum. The only exception involves persons who are known or suspected to have committed war crimes or crimes against humanity. It is the responsibility of the Lebanese

government to ensure that the international community is informed of the individuals known or suspected to have committed war crimes during the occupation of southern Lebanon.

Thorough, independent, and transparent investigations by the commission of inquiry would enable judicial authorities in the countries where former miliamen are currently living, or where they are seeking political asylum, to identify and search for such persons. If the Lebanese government wishes to request the return of these individuals to Lebanon for prosecution, it should publicly pledge that they will not be held in incommunicado detention and at risk of torture, that they will be tried fairly in civilian courts, and that they will not face the death penalty. If states are unable or unwilling to return suspects to Lebanon, they should be brought to justice in their country of current residence, which is required under international law.

The commission should also disseminate its findings with respect to Israelis implicated in war crimes in south Lebanon, including descriptions of specific acts and incidents where perpetrators are not known and additional investigation in Israel is required. This would enable Israeli human rights lawyers and nongovernmental organizations to initiate their own efforts to pursue justice.

***

We would welcome the opportunity to discuss these important matters with appropriate government officials in Beirut. Thank you in advance for your attention, and I look forward to hearing from you at your earliest convenience.

Sincerely,

Hanny Megally

Executive Director

Middle East and North Africa Division

Human Rights Watch

cc:

His Excellency Farid Abboud, Embassy of Lebanon, Washington, D.C.