Democratic Republic of Congo in Crisis

We are no longer updating this blog. For more information about Human Rights Watch’s reporting on Congo, please visit: https://www.hrw.org/africa/democratic-republic-congo.

The year 2017 will be critical for the Democratic Republic of Congo. After much bloodshed and two years of brutal political repression leading up to and following the December 19, 2016, deadline that marked the end of President Joseph Kabila's constitutionally mandated two-term limit, participants at talks mediated by the Catholic Church signed an agreement on New Year's Eve 2016. It includes a clear commitment that presidential elections will be held before the end of 2017, that President Joseph Kabila will not seek a third term, and that there will be no referendum nor changes to the constitution. While the deal could prove to be a big step toward Congo's first democratic transition since independence, there's still a long road ahead.

Human Rights Watch's Congo team will continue here to provide real-time updates, reports from the field, and other analysis and commentary to help inform the public about the ongoing crisis and to urge policymakers to remain engaged to prevent an escalation of violence and abuse in Congo -- with potentially volatile repercussions across the region.

The Congolese Government Is at War with Its People

Published in openDemocracy

The government of the Democratic Republic of Congo is putting its own short-term interests over the well-being of the Congolese people. It is refusing to attend and encouraging others to stay home from today’s international conference in Geneva, a United Nations-led initiative to raise $1.7 billion for emergency assistance to over 13 million people in Congo affected by recent violence.

Government officials deny that there’s a humanitarian crisis. This appears related to a sinister attempt to attract foreign investment and further enrich those in power, while avoiding outside scrutiny.

Congolese security forces and armed groups have killed thousands of civilians in the past two years, adding to at least six million Congolese who have died from conflict-related causes over the past two decades – making the conflict in Congo the world’s deadliest since World War II. Today, some 4.5 million Congolese are displaced from their homes – more than in any other country in Africa. Tens of thousands have fled into Uganda, Angola, Tanzania, and Zambia in recent months – raising the specter of increased regional instability.

Congo is Africa’s biggest copper producer and the world’s largest source of cobalt–which has tripled in value in the past 18 months because of the demand for electric cars. Hundreds of millions of dollars of mining revenue have gone missing in recent years, as Kabila and his family and close associates have amassed fortunes. While Congo’s immense mineral wealth could help address the emergency and other basic needs of an impoverished population, income from any new investments are more likely to end up in the pockets of those in power.

Much of the recent violence is linked to the country’s worsening political crisis. President Joseph Kabila has delayed elections and used violence, repression, and corruption to entrench his hold on power beyond the end of his constitutionally mandated two-term limit on December 19, 2016.

Kabila has presided over a system of entrenched impunity in which those most responsible for abuses are routinely rewarded with positions, wealth, and power. Congolese security forces have carried out or orchestrated much of the violence, in some cases by creating or backing local armed groups. Well-placed security and intelligence sources have told us that efforts to sow violence and instability are an apparently deliberate “strategy of chaos” to justify further election delays.

Congolese security forces shot dead nearly 300 people during political protests over the past three years. Since December, security forces have hit a new low by firing into Catholic church grounds to disrupt peaceful services and protest marches following Sunday mass.

Meanwhile, attacks on civilians have intensified in eastern Congo’s Ituri province over the past three months. We have documented terrifying accounts of massacres, rapes, and decapitation. More than 200,000 people have been forced to flee their homes.

While government officials have insisted that the recent violence is the consequence of inter-ethnic tensions, baffled residents say that isn’t so. Many referred to an “invisible hand” – seemingly professional killers came into their villages and hacked people to death in what appeared to be well-planned assaults. Some alleged that government officials may be involved.

But Congo’s deputy minister for international cooperation said last week that “there is no humanitarian crisis.” Congo’s foreign minister said the UN’s description of the humanitarian situation in Congo is “counterproductive for the public image and attractiveness of our country and could scare away potential investors.”

Congolese government officials sent threatening letters to the Netherlands and Sweden, who are supporting the conference, saying Congo would be “forced to impose consequences” if they continue with their preparations, and they successfully convinced the United Arab Emirates to pull out.

Donors should not be intimidated. They should instead work to ensure that adequate funds are raised to meet the life-threatening humanitarian and protection needs of the Congolese people. And just as important, they should work to address the underlying causes of the violence to prevent the crisis from spiraling out of control even further.

That means working closely with regional leaders to ensure Kabila steps down in accordance with the constitution and allows for the organization of free, fair, and credible elections. Congolese need an opportunity to elect a new president who is accountable to the people and who will work to bring an end to Congo’s violence, impunity, and suffering. The Congolese people deserve no less.

Congo’s Kabila Ignores Political Crisis Amid New Repression

A rare press conference by President Joseph Kabila on Friday signaled that the Democratic Republic of Congo’s political crisis was far from resolved and that further repression and restrictions on free expression and assembly may be in store.

As concern has grown over the deadly consequences of Kabila’s efforts to remain in power beyond his constitutionally mandated two-term limit, which ended in December 2016, there have been increasing calls domestically and internationally for Kabila to state explicitly he will not be a candidate in proposed December 2018 elections, and not seek to amend the constitution, and that he will step down by the end of 2018. Among those weighing in was a bipartisan group of United States senators in a letter sent to Kabila last week.

In the press conference – his first in five years - Kabila made none of those commitments. While claiming the electoral process was “resolutely under way,” he said only the national electoral commission (CENI) is empowered to decide when exactly the poll will be held. When a journalist asked Kabila whether he would run again, he didn’t say no but asked that a copy of the constitution be given to her.

Despite the rights of Congolese to demonstrate peacefully under the constitution and international law, Kabila said a new law is needed to “reframe” the legality around such demonstrations, noting that “democracy isn’t a fairground.” He claimed to have “burst out in laughter” when he sees those who “pretend to defend the constitution.” Unfortunately, what Kabila considers to be a laughing matter has been the security forces shooting dead, wounding, and jailing hundreds of people peacefully calling for the constitution to be respected.

Kabila also questioned the price tag on the electoral process, which he said could come at the cost of the country’s development: “Should we be cited as the most democratic country in the world, or is development what matters?” he said. “When the time comes,” he added, “courageous decisions” will need to be made. Was this a veiled reference to an upcoming referendum or change to the electoral process that would allow Kabila to stay in power?

Kabila’s remarks came two days after the United Nations human rights office in Congo reported that some 1,176 people were extrajudicially executed by Congolese “state agents” in 2017, representing a threefold increase over two years.

On January 21, thousands of Catholic worshipers and other Congolese protested in several cities and towns, calling for Kabila to step down and allow for the organization of elections. Security forces responded with unnecessary or excessive force, firing teargas and live ammunition to disperse crowds. At least seven people were killed, according to Human Rights Watch’s research, including a 24-year-old woman studying to be a nun, shot dead right outside her church. The January 21 crackdown followed similar protests called by Congo’s Catholic Church lay leaders after Sunday Mass on December 31, when security forces killed at least eight people and injured or arrested scores of others, including many Catholic priests.

Over the past three years, Kabila and those around him have used one delaying tactic after another to postpone elections and entrench their hold on power through brutal repression, largescale violence and human rights abuses, backed by systemic corruption. A Catholic Church-mediated power sharing agreement signed on New Year’s Eve 2016 provided Kabila another year in power – beyond the end of his constitutional term limit – to implement a series of confidence building measures and organize elections by the end of 2017. But instead, these commitments were largely flouted. Despite CENI’s publication of the electoral calendar on November 5 – which set December 23, 2018 as the new date for elections, with the caveat that numerous “constraints” could push the date back even further – Kabila has not demonstrated that he is preparing to step down, or create a climate conducive to the organization of free, fair, and credible elections.

While some of Congo’s international partners have increased pressure on Kabila’s government, more needs to be done to show that there will be real consequences for further attempts to delay elections and entrench his presidency through repression. Belgium recently announced it is suspending all direct bilateral support to the Congolese government and redirecting its aid to humanitarian and civil society organizations. Other donors should follow suit. In December the US sanctioned Israeli billionaire Dan Gertler, one of Kabila’s close friends and financial associates who “amassed his fortune through hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of opaque and corrupt mining and oil deals” in Congo, as well as a number of individuals and companies associated with Gertler. Yet the impact of these actions would be much greater if the UN Security Council, the European Union, and the US work together to expand targeted sanctions against those most responsible for serious human rights abuses in Congo and those providing financial or political support to the repressive tactics.

Ultimately, Congo’s partners are going to need to decide whether their interests lie with supporting an abusive, dictatorial government, or with respecting and advancing the rights of the Congolese people – and what that means in terms of concrete action.

15-Year-Old Peaceful Protester Beaten and Detained

On Wednesday, Binja Happy Yalala, a 15-year-old secondary school student on Idjwi Island in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, was beaten by police who accused her of being a sorcerer and detained her for over 10 hours. Her actual “crime” was that she had participated in a peaceful march organized by the citizens’ movement “C’en Est Trop” (“This is Too Much”).

The marchers were responding to a call from other citizens movements and civil society groups, and backed by political opposition leaders, for Congolese to mobilize on November 15 and demand that President Joseph Kabila leave office by the end of 2017 in accordance with the constitution and the New Year’s Eve agreement signed late last year.

The Idjwi protesters arrived at their local administrative office, singing the national anthem, to deliver a memo when the police commander gave the order to arrest them.

“The police immediately followed the order with brutality and violence,” said Binja’s father, who had joined the march with his daughter. “Some of us started to run, but others were taken immediately, including myself. They beat us with their fists and batons and kicked us. They said to us: ‘You all are rebels. We’re the ones who control the law. You will see how we’ll make you suffer.’”

When Binja saw her father and the others being arrested, she said she couldn’t just stand by and watch.

“I was scared, but it also made my heart ache because I didn’t understand what my father and the others had done wrong,” Binja told Human Rights Watch. “So I went up and asked the police to let them go. When they didn’t listen to me, I told them that I wasn’t going to leave without my father, so if they don’t release him they should arrest me too. Then without hesitating, one of them grabbed me roughly by the arm, beat my back with his gun, and tied my hands tightly behind my back. It hurt a lot, and I cried out. They then put me in the cell with my father and the others.”

Binja, her father, and the 11 others detained were soon taken to Idjwi territory’s main prison.

“They asked us a lot of questions about what had happened,” Binja said. “They beat my father because they said he had taught me things. He tried in vain to explain that I wasn’t a member of the movement. They then accused me of being a sorcerer, and they beat me again with their batons.”

Binja said that when they were all finally released about 10 p.m., she hurt all over and could barely walk.

In total, Congolese security forces detained at least 52 people on November 15 while they were participating in or planning small marches and demonstrations in Goma, Kasindi, Kindu, Kisangani, Kinshasa, and Idjwi. Most were later released, but eight remain in detention, including six in Goma and two in Kinshasa.

Two activists who police arrested in Goma on Monday while encouraging people to join the planned protests were still in detention.

On November 14, the day before the protests, the provincial police commander in Goma had instructed his forces to “mercilessly repress” the planned demonstrations, in a filmed message that was widely shared on social media.

The next morning, many people across Congo – including in Kinshasa, Lubumbashi, Mbandaka, Matadi, Mbuji-Mayi, Kananga, Goma, Idjwi, Beni, Kasindi, Butembo and Kisangani – woke up to the sight of a heavy deployment of security forces on their cities’ main roads. In several cities, streets were less crowded than usual, shops and markets remained closed, and many students stayed home from school. People stayed home as a sign of protest or to stay safe from any violent crackdown, or both. The few protesters who dared go out on the streets were often quickly arrested by security forces or dispersed by teargas.

The United Nations peacekeeping mission in Congo (MONUSCO) had urged Congolese authorities on November 14 to respect “the freedom to demonstrate in a peaceful and restrained manner” and to “allow all voices to express themselves calmly and peacefully.” The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights reinforced this appeal, calling on Congolese authorities to “halt the inflammatory rhetoric against protestors” and to ensure security personnel “receive clear instructions that they will be held accountable for their conduct during law and order operations in the context of demonstrations, regardless of their ranks or affiliation.”

In a joint statement published yesterday, the European Union, American, Swiss, and Canadian missions in Congo called on Congolese security forces to refrain from the excessive use of force and warned that those responsible could be held to account, including in an individual manner.

Many political prisoners and activists, arrested during previous political demonstrations or for their participation in other peaceful political activities, remain in detention. For a list and summary of a selection of these cases, please see here.

Congolese authorities should immediately release all those held for the peaceful expression of their political views, and should start working to create a climate conducive to the organization of free, fair elections.

New DR Congo Electoral Calendar Faces Skepticism Amid More Protests, Repression

The Democratic Republic of Congo’s national electoral commission (CENI) has set December 23, 2018 as the date for presidential, legislative, and provincial elections – more than two years after the end of President Joseph Kabila’s constitutionally mandated two term-limit.

According to the calendar released yesterday by the CENI, the new president would be sworn in on January 12, 2019, and the whole electoral cycle, including local elections, would continue until February 16, 2020. As with past electoral calendars that CENI and government officials have blatantly disregarded, the new calendar includes a list of 15 legal, financial, and logistical “constraints” that could impact the timeline.

The CENI’s announcement comes about a week after the United States ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley visited Congo, where she announced before meeting with Kabila that Congo’s long-delayed elections must be held by the end of 2018 or they would not receive international support.

While some diplomats might see the new calendar as a sign of progress, many Congolese are rightly skeptical. Over the past several years, Kabila and his coterie have blocked the organization of elections as the deadline for when he needs to step down keeps getting extended. Senior US officials and other diplomats delivered similar messages to Kabila in the lead-up to December 19, 2016, the end of Kabila’s two-term limit. When that deadline passed with no progress toward elections, the UN Security Council and others pressed Kabila to organize elections by the end of 2017, in accordance with a Catholic Church-mediated power sharing arrangement signed on December 31, 2016, known as the New Year’s Eve agreement.

Kabila and his ruling coalition then disregarded the main terms of the agreement, as Kabila entrenched his hold on power through corruption, large-scale violence, and brutal repression against the opposition, activists, journalists, and peaceful protesters. Security force officers went so far as to implement an apparently deliberate “strategy of chaos” and orchestrated violence, especially in the southern Kasai region, where up to 5,000 people have been killed since August 2016. Government and CENI officials have announced since July that elections could not be held in 2017 as called for in the New Year’s Eve agreement, ostensibly due to the violence in the Kasais.

Meanwhile, there has been no independent oversight or audit of the ongoing voter registration process. Civil society organizations and political opposition leaders have raised concerns about possible large-scale fraud. Some fear a deeply flawed electoral list could be used to push through a constitutional referendum process that could remove term limits and allow Kabila to run for a third term. Kabila himself has repeatedly refused to say publicly and explicitly that he will not be a candidate in future elections. The extra year the new calendar gives Kabila allows him more time to attempt constitutional or extra-constitutional means to stay in power.

The Struggle for Change (LUCHA) citizens’ movement strongly denounced the calendar presented by the CENI yesterday as “fantasy” and called on the Congolese people to mobilize to defend themselves peacefully against the “shameful maneuver by Kabila and his regime to gain more time to accomplish their goal of staying in power indefinitely.” LUCHA stated that the movement no longer recognizes Kabila and his government as the legitimate representatives of the Congolese people and urged Congo’s international partners to do the same.

Other citizens’ movements, human rights activists, and opposition leaders made similar calls, denouncing the new CENI calendar, urging the Congolese people to mobilize, and calling for a “citizens’ transition” without Kabila to allow for the organization of credible elections.

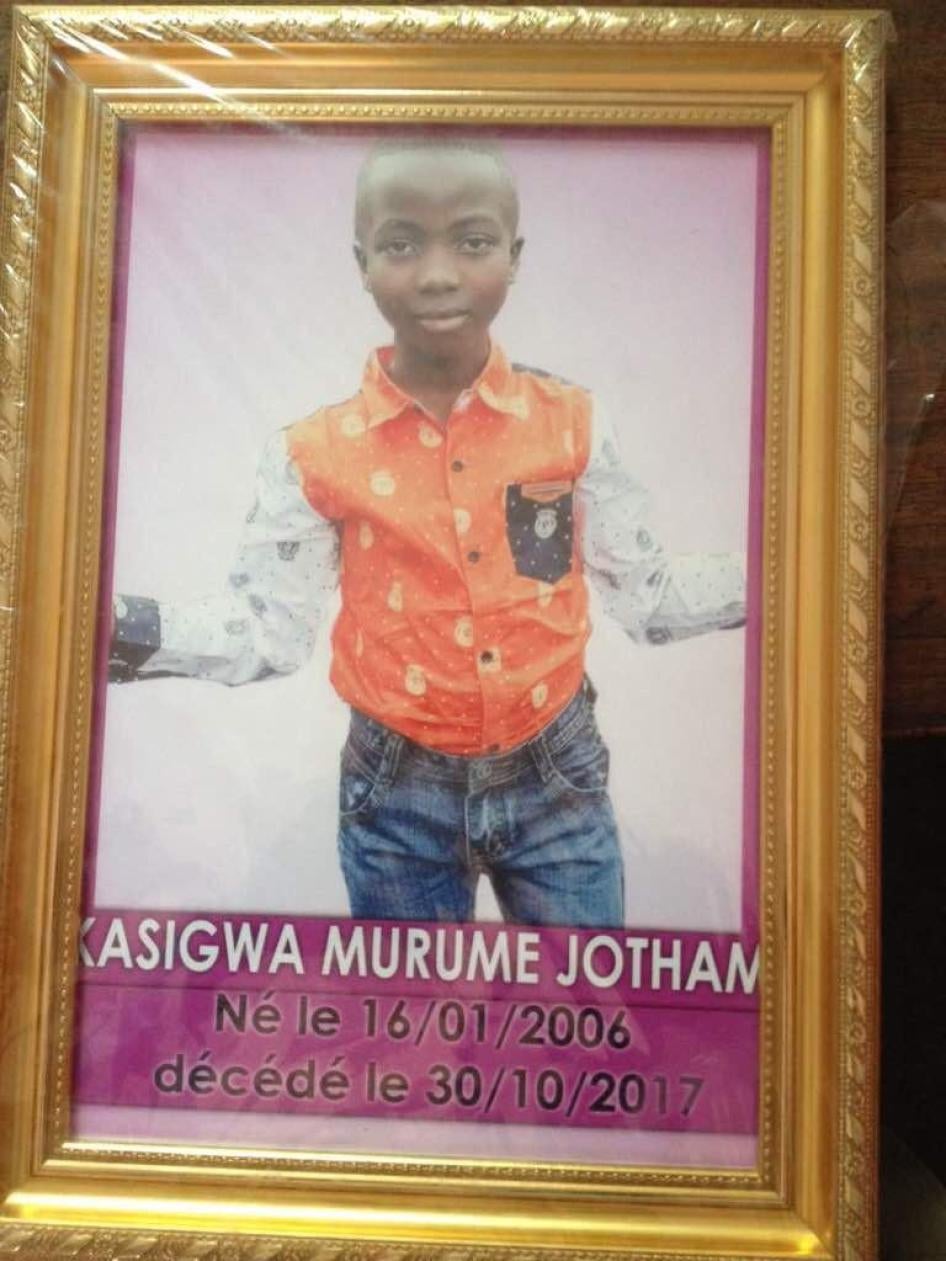

Meanwhile, the repression against opposition leaders and supporters, human rights and pro-democracy activists, peaceful protesters, and journalists has continued unabated. Security forces arrested around 100 opposition party supporters and pro-democracy activists during protests in Lubumbashi, Goma, Mbandaka, and Beni over the past two weeks. Many of them were later released. During the protest in Goma on October 30, security forces shot dead five civilians, including an 11-year-old boy, and wounded 15 others.

More protests are planned across the country in the coming days to reject the CENI’s newly announced calendar. Congolese government officials and security forces should not use unnecessary or excessive force against protesters, tolerate peaceful protests and political meetings, and allow activists, opposition party leaders, and journalists to move around freely and conduct their work independently, without interference.

Congo’s international partners, including the UN peacekeeping mission in Congo, should work to protect peaceful protesters and individuals at risk and show their support for the Congolese people’s quest for a more democratic and rights-respecting future.

Three-Year Mystery Behind DR Congo’s Beni Massacres Unravels

New research has cast light onto one of the Democratic Republic of Congo’s most gruesome mysteries – the slaughter of more than 800 people in Beni territory that began three years ago this week.

The more than 120 massacres in eastern Congo, in which assailants methodically hacked people to death with axes and machetes or fatally shot them, continued through August this year and have baffled analysts. But a new investigative report by the New York University-based Congo Research Group offers a breakthrough in understanding the dynamics and gives hope that perpetrators will one day face justice.

Based on two years of painstaking research, the report identifies distinct killing phases and an array of diverse armed actors responsible for the massacres: the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), an Islamist Ugandan rebel group based in eastern Congo; former officers from the Congolese Patriotic Army (APC); the armed branch of the Congolese Rally for Democracy-Liberation Movement (RCD-ML), the Ugandan-backed rebellion during Congo’s second war from 1998 to 2003; and various other local militia groups; as well as elements of the Congolese army. Instead of the killings being committed by a cohesive group with a singular political agenda, these actors constantly shifted alliances fighting alongside and against each other.

During the Rwandan-backed M23 rebellion in eastern Congo in 2012 and 2013, remnants of the APC in Beni territory mobilized and established an informal alliance with the M23 fighters, according to the report. After the M23 was defeated in November 2013, the Congolese army turned its focus to Beni, officially to defeat the ADF rebels, who had been present on Congolese territory for many years. According to the report, former APC officers in Beni perceived these operations as an attempt to dismantle the lucrative political and economic networks they had established in Beni, including through collaboration with the ADF and other local militia groups. In response, they orchestrated the first of a series of small-scale killings in Beni in 2013. These initial attacks were reportedly meant to show the Congolese government’s failure to protect the population, and thereby delegitimize its authority and pave the way for a new rebellion.

Once the killings began, some Congolese army officers under the command of Gen. Akili Mundos decided to co-opt the network of former APC officers, ADF combatants, and other local militia fighters, the report found. Instead of ending the violence, the army began working together with members of the same network responsible for the initial killings, allowing the killings to continue on a much larger scale starting in October 2014.

With Pandora’s Box opened, the web of foes and friends changed constantly with various local militia groups taking a more prominent role as the massacres continued. All the while, the Congolese government blamed all the violence on so-called “radical ADF terrorists,” in an apparent attempt to mislead the Congolese population, foreign diplomats, journalists, and the United Nations peacekeeping mission in Congo, which continued to provide uncritical support to the army.

While there are still many unanswered questions, the new Congo Research Group report sheds important light on those responsible for the Beni massacres. It should serve as a basis for credible judicial investigations as well as targeted sanctions by the UN Security Council and others.

International attention on Congo has shifted from the Beni crisis to Congo’s southern Kasai region, where new massacres have killed more than 5,000 people and displaced some 1.4 million from their homes since August 2016, according to the UN. To finally break these devastating cycles of violence and impunity, the Beni massacres cannot be forgotten. Strong action is needed to show that there are consequences for those responsible – no matter their rank or position.

Congolese Authorities Arrest, Later Release 49 Activists Holding Anti-Kabila Protests

On September 30, Democratic Republic of Congo security forces arbitrarily arrested 49 activists from several citizens’ movements protesting the failure to hold presidential elections before the end of the year.

Activists from Struggle for Change (LUCHA), Countdown (Compte à Rebours), and Bell of the People (Kengele ya Raia) were arrested in Congo’s eastern cities of Goma and Kisangani. Small protests were also held in Bukavu and Bandundu.

The activists were peacefully protesting the electoral commission’s failure to call the presidential elections in time for them to be held before December 31, 2017, as called for in the Catholic Church-mediated agreement signed on December 31, 2016. Under Congo’s constitution, national elections need to be announced at least three months before the voting date, which means the deadline to hold elections during 2017 has now passed.

In Goma, activists tried to deliver a letter to the electoral commission’s office, but they were prevented by riot police. “They cornered us with two police trucks and tried to take our banners from us,” one LUCHA activist told Human Rights Watch. “Some of us managed to get away but the rest of us were forced onto the police trucks.”

The 16 activists arrested in Kisangani were released later that day, while the 33 activists in Goma were released three days later without charge. These latest arrests show the government’s intent to quickly quash peaceful protests before they build momentum.

Last week, four LUCHA activists in Mbuji-Mayi – Nicolas Mbiya, Josué Cibuabua, Mamie Ndaya, and Josué Kabongo – were released from prison. They had been arbitrarily arrested in mid-July for investigating the voter registration process in Kasai Oriental province. Mbiya and Cibuabua had already been detained for nearly a week in May for demanding the publication of an electoral calendar. Earlier, from December 2016 to February, Mbiya was also detained with another LUCHA activist, Jean Paul Mualaba Biaya, for protesting President Joseph Kabila’s decision to stay in power beyond his constitutionally mandated two-term limit.

The September 30 protests came a week after President Kabila’s address to the United Nations General Assembly in New York. In his public remarks and in reports that have emerged about his private meetings with various foreign officials in New York, Kabila did nothing that would suggest that he is preparing to leave power, making no clear commitments about when elections would be held or that he would not be a candidate.

Earlier this week, a coalition of United States senators led by Cory Booker wrote to US President Donald Trump, urging the US government to “use the means at our disposal” if the Congolese government continues to refuse to implement the “spirit and letter” of the December 31, 2016 agreement, “including sanctions designations under Executive Order 13671 on DRC, anti-money-laundering regulations, and additional tools available under the Global Magnitsky Act – to affect the incentives of individuals who have strong influence over President Kabila to incentivize them to urge him to change course.”

The US – and Congo’s other international partners, including the European Union – would do well to act now, before it’s too late and more Congolese pay the price for Kabila’s unconstitutional intransigence.

Heavy Fighting in Eastern DR Congo, Threats to Civilians Increase

The risk of increased violence and deteriorating security for civilians in South Kivu province in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo has spiked sharply, as a coalition of armed groups moved in on the province’s second largest city, Uvira, last week.

The potentially destabilizing impact of a brewing rebellion in the midst of Congo’s ongoing political crisis does not bode well for civilians, already fatigued from two decades of conflict.

The stated goal of the so-called National People’s Coalition for the Sovereignty of Congo (Coalition nationale du peuple pour la souveraineté du Congo, CNPSC) is to topple the government of President Joseph Kabila, who they say is illegitimate following his refusal to step down at the end of his constitutionally mandated two-term limit last December. The coalition, which includes at least several hundred fighters from numerous armed groups, has also been referred to as the Alliance of Article 64, a reference to Article 64 of the constitution, which says the Congolese people have an obligation to thwart the efforts of those who seek to take power by force or in violation of the constitution.

Others suggest this is an effort by the Congolese government to stoke further chaos and justify election delays, just as the violence in the Kasais has been used as the main excuse for why elections won’t be held before the end of 2017, as called for in the Catholic Church mediated agreement of last December.

The coalition began fighting the Congolese army in late June in Maniema province and Fizi, the southernmost territory of South Kivu, and has moved steadily north, and taken control of several villages along Lake Tanganyika in the past week. The Congolese army and United Nations peacekeepers sent in reinforcements and have kept the rebels out of the city of Uvira, a strategic trading hub.

More than 100,000 people have been displaced since the fighting began in June, and the Congolese army reportedly arrested scores of local youth suspected of having links with the coalition.

The CNPSC is led by self-proclaimed “General” William Yakutumba, commander of one of the most powerful armed groups in South Kivu, which is largely made up of ethnic Bembe fighters. His “Mai Mai Yakutumba” group has committed many abuses over the past decade, including attacks on aid workers, large-scale theft of cattle, piracy on Lake Tanganyika, and illegal exploitation of gold and taxation of the population. The group claims to represent the interests of various local ethnic groups and to protect them against those they perceive as “foreigners,” especially members of the Banyamulenge, a minority ethnic group in the province.

The CNPSC’s move on Uvira came less than two weeks after Congolese security forces used excessive force to quash a protest at a Burundian refugee camp in Kamanyola, to the north of Uvira, killing around 40 Burundian refugees and wounding more than 100 others. A security force officer was also killed.

The show of force by the CNPSC and increased armed mobilization in South Kivu around the national political crisis is a bad omen for Congo. With Kabila bent on staying in power, violence and instability will likely only increase, with ordinary civilians bearing the brunt of it.

Congo Should Release All Political Prisoners

The Democratic Republic of Congo should release the dozens of people detained simply because of their political views or for exercising the rights to peaceful protest or free expression.

Yesterday, Human Rights Watch joined 44 international and Congolese rights organizations in an urgent appeal, calling for the release of nine human rights and pro-democracy activists detained in Lubumbashi and Mbuji-Mayi. Human Rights Watch also published a list list today, detailing 30 people arrested between January 2015 and July 2017 – a small sample of the hundreds arbitrarily arrested in the sweeping crackdown of those opposed to President Joseph Kabila’s extending his hold on power.

These individuals, who are all still in detention, include political opposition leaders and supporters, human rights and pro-democracy youth activists, journalists, and those suspected of having links to political opposition leaders. Many have been held for weeks or months in secret detention, without charge and without access to families or lawyers. Some allege they were mistreated or tortured and some are suffering serious health complications. Many were put on trial on trumped-up charges.

This list is not exhaustive and only includes cases in which Human Rights Watch was able to confirm the circumstances of arrest. Hundreds of other protesters and political opposition supporters have been arrested over the past three years, many of whom remain in detention. Because Human Rights Watch has not confirmed the grounds for their arrests, these additional cases are not included in our list.

Human Rights Watch has also documented the cases of 222 prisoners arrested since January 2015 who were subsequently released, often after months of arbitrary detention.

Congolese authorities should ensure all detainees have access to necessary medical care, their family members, and a lawyer. All those detained because of peaceful political views or activities or alleged connections to political opposition leaders should be released immediately and cleared of all charges. Congolese authorities should also investigate and appropriately sanction and prosecute security force, intelligence, and government officials implicated in cases of illegal arrest and detention, mistreatment or torture, and political interference in judicial proceedings.

Human Rights Watch’s list of political prisoners in detention can be found here.

Detained Opposition Leader Forcibly Removed from Hospital

Congolese opposition leader Franck Diongo has told Human Rights Watch that Congolese military intelligence officials and Republican Guard soldiers removed the intravenous drip and dragged him out of his hospital bed in Kinshasa, capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo, last Thursday, August 31. Diongo was then taken back to Kinshasa’s central prison.

Diongo, who appeared to be in a seriously weakened state when he spoke to Human Rights Watch, said that the Republican Guard and military intelligence soldiers showed no documents and did not speak to the doctors before forcing him to leave the hospital. In a letter sent on Sunday to a doctor who treated him in the past, quoted by Actualité.cd, Diongo writes that he “vomits blood” and suffers from “severe headaches and stomach pains,” and asks to be returned to the hospital. Denial of medical care in such cases amounts to cruel and inhuman treatment in violation of the Convention Against Torture, to which Congo is a party.

Diongo is president of the opposition party Movement of Progressive Lumumbists (MLP), part of the Rassemblement opposition coalition. He was a member of parliament at the time of his arrest.

Authorities in Kinshasa arrested Diongo on December 19, 2016, the last day of President Joseph Kabila’s second and final term in office, after Diongo and his colleagues allegedly apprehended, held, and beat three Republican Guard soldiers wearing civilian clothes. Diongo said he feared they had been sent to attack him. “Security forces staged a stunt to arrest me,” he later told us.

Diongo was detained in several locations and says he was severely beaten in the following days, including at the Tshatshi military camp and the military intelligence headquarters in Kinshasa. According to the United Nations, Diongo was “subjected to cruel, inhumane or degrading treatments” while he was held by military intelligence officers.

Congo’s Supreme Court of Justice sentenced Diongo to five years in prison on December 28, 2016, following a hasty trial that he attended in a wheelchair and on an intravenous drip, which his lawyers said was due to the treatment he endured during arrest and detention. According to Diongo and his lawyers, this amounted to torture. Diongo was convicted of “aggravated arbitrary arrest” and “illegal detention.” As a member of parliament, Diongo was tried by the Supreme Court; he has no possibility to appeal the judgement.

After his conviction, Diongo was sent to Kinshasa’s central prison, still in a wheelchair. As Diongo’s health continued to deteriorate, the doctor treating him in prison submitted a report to the prison’s director, who then wrote to the minister of justice, asking for Diongo to be treated in a specialized hospital. Diongo was finally transferred to the Centre Médical de Kinshasa on August 18. As his treatment was ongoing, Diongo was then forcibly removed from this hospital last Thursday.

In June, Diongo’s lawyers submitted a request in his name to the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention. The document, seen by Human Rights Watch, argues that Congolese authorities did not respect minimum fair trial standards and that Diongo was targeted because of his political opinions. They also made the case that Diongo’s right to his conviction and sentence being reviewed by a higher tribunal was violated given that he was convicted in the first and last instance by the Supreme Court. If the Group decides that “the arbitrary nature of the deprivation of liberty is established,” it will render an opinion to that effect and make recommendations to the Congolese government.

Diongo also faced problems attempting to register to vote, which would be a pre-condition for him to run again for parliament or another office. On June 21, when other prisoners were registering to vote, the director of the voter registration center at Kinshasa’s central prison did not allow Diongo to register, without offering any reason. While Diongo’s conviction stripped him of his status as a member of parliament, he did not lose his civil and political rights, including the right to register to vote.

“The members of my political party and myself are victims of persecution and harassment,” Diongo told Human Rights Watch. “I am a fierce opponent who refused to participate in the two dialogues with Joseph Kabila … knowing that President Kabila is not a sincere person, and that he’d only want to buy time to extend his presidency.”

Congolese authorities should urgently ensure that Diongo is given the medical care he needs, that he can register to vote like other Congolese citizens, and that the legality and necessity of his detention are reviewed, given the serious irregularities and mistreatment surrounding his case.

Across the Democratic Republic of Congo, dozens of political opposition members and activists are in detention for participating in peaceful demonstrations, speaking out against election delays, or criticizing government policies. Many have been held in secret detention without charge or access to family or lawyers. Others have been put on trial on trumped-up charges. Many suffer regular beatings and horrendous living conditions, which have received little international attention.

‘Manifesto of the Congolese Citizen’ Calls for a Transition without Kabila

Today, about 40 leaders of citizens’ movements, civil society organizations, Catholic Church representatives, and other independent Congolese leaders launched the “Manifesto of the Congolese Citizen,” following a three-day meeting in Paris to discuss the “return of constitutional order” to the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The two-page document makes the case that President Joseph Kabila has violated the country’s constitution by using “force and financial corruption” to stay in power and “entrench his regime of depredation, pauperization, and the pillaging of the country’s resources for the benefit of himself, his family, his sycophants, and his foreign allies in Africa and beyond.”

It further states that Kabila and a “group of individuals” have “deliberately refused to organize elections,” in defiance of the constitution’s two-term presidential term limit and the Catholic-Church mediated New Year’s Eve agreement, a power-sharing deal calling for elections to be held by December 2017. In doing so, “zones of insecurity” and “deadly tragedies” have emerged across the country, “as part of a clear objective” to declare a “state of emergency” and delay elections, while “terror has once again become the preferred method of government, making it impossible for the Congolese people to claim their rights,” according to the document.

The manifesto calls on the Congolese people “to perform their sacred duty, using peaceful and non-violent means, to thwart President Joseph Kabila’s attempt to remain in power after December 31, 2017, in application of Article 64 of the constitution.” It “demands the resignation” of Kabila and calls for a “citizens’ transition” whose primary objective would be the organization of credible elections, and which would be led by leaders who could not be candidates in the future elections and who would be appointed after national consultations.

The document also called for the immediate and unconditional release of political prisoners and the reopening of media outlets, and for security forces to “protect” citizens and not allow themselves to be “used as instruments of repression.”

“All citizens of Congo” are called upon to “adhere massively” to the manifesto, and to “participate actively in the campaign of peaceful and non-violent actions to bring about a return to constitutional, democratic order.”

Finally, the document calls for a “new system of governance … built on an independent judiciary, security services who are there to protect our citizens, free expression of our constitutional freedoms, transparent and fair management of all national resources, and strong and democratic institutions that put the interests of the Congolese citizen at the heart of every political initiative.”

The participants at the Paris meeting, which was initiated by the Institute for Democracy, Governance, Peace, and Development in Africa, also worked to develop an “action plan” for peaceful mobilization.