Financially Helping Others

Of the 110 respondents, 102 said they financially support themselves. In addition, a strong majority-84 percent-reported financially assisting other people since being released from prison. They described providing this support to a range of people, from family and friends to community members, such as veterans and unhoused people.

Supporting Unhoused Populations

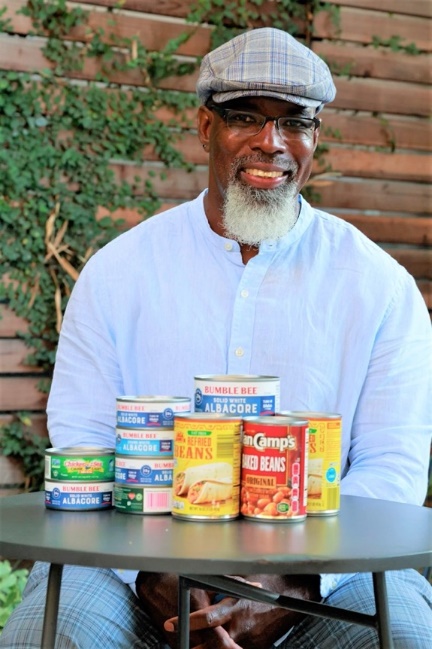

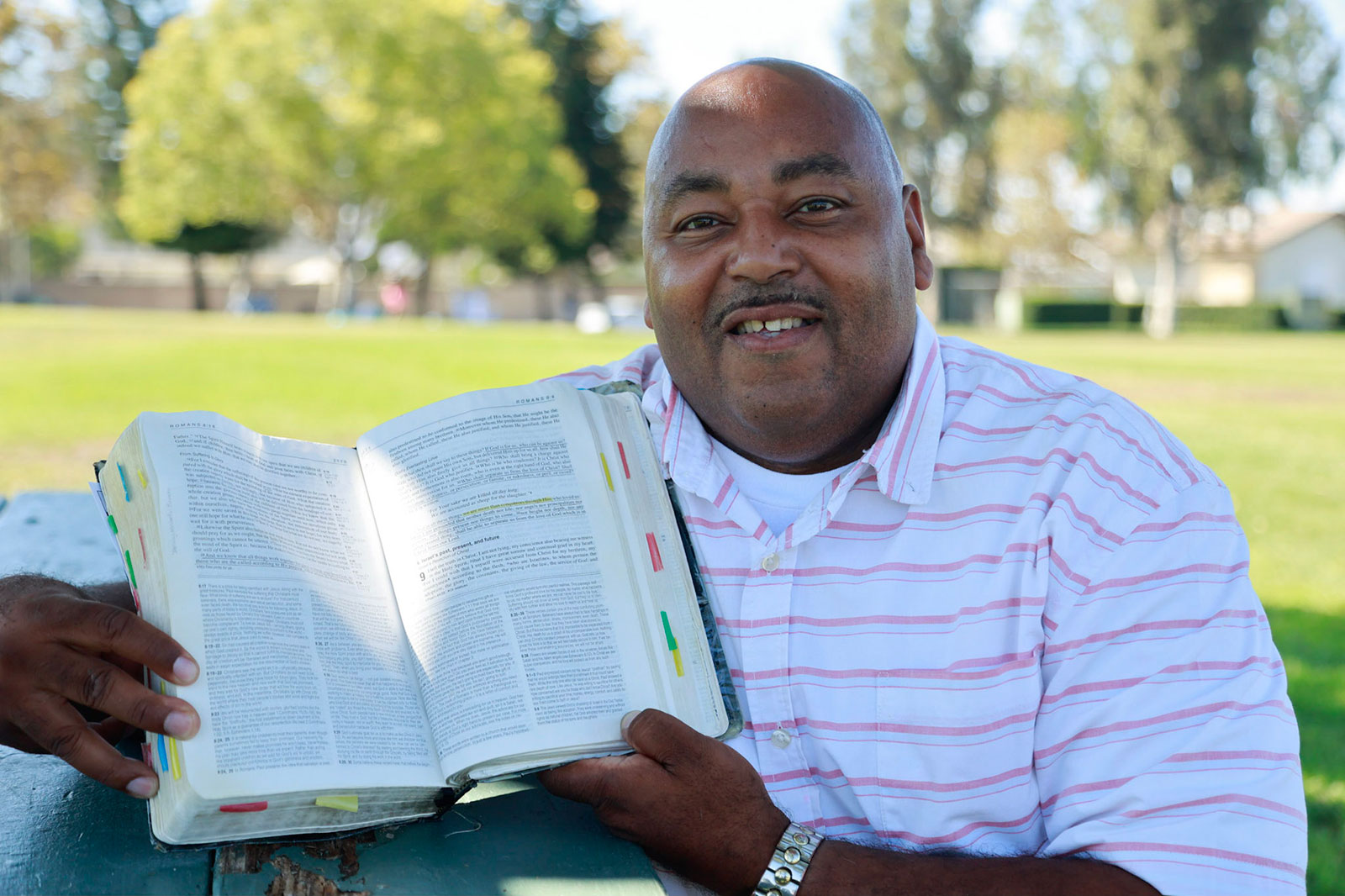

The act of financially helping unhoused people emerged as a common theme among respondents. After being released in 2018, DeAngelo M. now works as a pastor at a church and runs a non-profit in Los Angeles, but in his free time, he noted:

Me and my wife, we feed the homeless downtown. We’ll go and buy hundreds and hundreds of socks, hundreds and hundreds of deodorants, combs, toothpaste, blankets, gloves, beanies, and food, and we’ll put together these kits, and we’ll get together and go down and just give them out.61

Similarly, Thomas W. mentioned: “Me and my fiancée feed the homeless. Using our own funds, we made 300 meals for Easter, and we handed them out to the homeless in LA. We do that every couple of months.”62

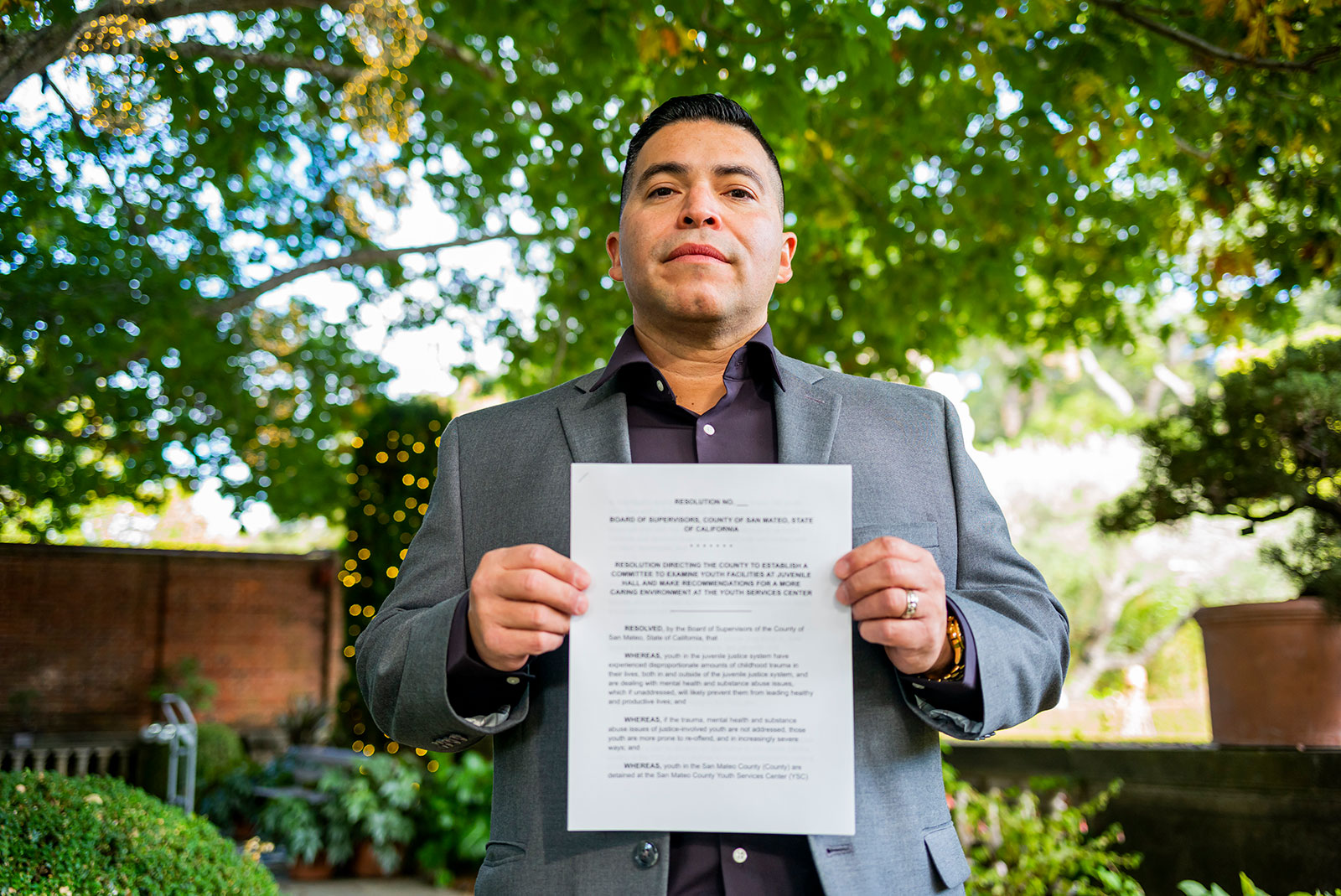

They described an affinity, noting that in some ways, the experience of an LWOP sentence was similar to that of people experiencing houselessness in feeling cast aside, despised, or forgotten by society. Juan C., who spent over 41 years in prison and is now almost 70 years old, contemplated:

So many [unhoused people] feel hopeless. People feel like they don’t really exist, don’t really matter. I try to help them up. I relate to them as human beings, not as homeless.63

James H. added: “I now have a soft spot in my heart for people experiencing homelessness and needing to panhandle. I have compassion for them because that’s what I feel happened to me.”64

Similarly, Howard J. remarked: “I give money to people who are homeless [because] someone looked out for me while I was in prison, and I see this as my time to give back and help others.”65

Supporting People Who Are Presently and Formerly Incarcerated

Of those financially assisting others, 37 percent said they help people who are currently incarcerated or have been recently released. “I know what it’s like to [be in prison and] feel like you need something but don’t have a way to get it,” Oliver T. says. “[In prison], people make 25 cents an hour at the most, so having a little money goes a long way.”66

Sara K., one of the first individuals in California to have an LWOP sentence commuted to a parole-eligible sentence, was released in 2013. She recently completed an inventory of her financial contributions over the past ten years and found that since being home, she has contributed over $20,000-mostly to individuals who are still incarcerated. “And I’m going to keep doing it,” she said. “I might be within the poverty line, but if I’m drinking coffee and eating a noodle, you’ll be drinking coffee and eating a noodle too.”67

They support people getting out of prison in other ways as well, often remembering the difficulties of reentering society. Michele S., who had only been released two months before her interview, noted:

[A]fter 30 years of being locked up, I have no idea how to navigate the DMV, or how to ride the bus, or how to get on the phone. There’s so many nuances to everyday living that people take for granted … to come out to the real world is a huge shift.68

Respondents reported that they hoped to ease the reintegration process for others by providing support such as transportation upon release, purchasing essential items like food and clothing, and helping with potentially overwhelming tasks such as navigating the Department of Motor Vehicles to obtain a state ID or driver’s license, or working with the federal government to obtain a social security card. Taewon W., who spent over 26 years in prison, said he now contributes ongoing financial assistance “to fellow LWOPers who [have been] released.” He described helping their transition:

I made sure that anyone else who was being released knew how to receive a social security card, food stamps, driver’s license, and anything they needed to function out here. I felt obligated to help those who would go through a similar process that I went through.69

Personal Relationships

Since being released from prison, the vast majority of respondents said they had established new relationships, nurtured or restored relationships with family members, and built new ties within the local community.

Establishing New Relationships

Nearly half had married or entered a committed relationship post-prison, and five had a new child. Others connect with children, often grown. “I talk on the phone every single day to my daughter,” said Kenneth H., additionally noting that “after I was released, I met a woman, and we have been partners for more than three years. I hope it lasts the rest of my life. It’s been a very good relationship.”70

People also have embraced new parental roles. Describing his wife’s eight-year-old daughter from a previous marriage, Matthew V. told us: “She comes in and calls me dad, and gives me hugs every morning. I teach her how to fight better in jujitsu so that boys don’t mess with her. She’s a tough one!”71

Nurturing and Repairing Relationships

Committing a crime and being sentenced to life without parole can harm relationships. Forty-five percent of respondents said they had worked to restore an estranged family relationship. For some, there has been healing and reconciliation. Roy C. said, “I’ve … been working on the broken relationships that I caused in my family. I’ve been reaching out to them, and they’ve been responding really well.”72 Similarly, Thaisan N. reflected that:

Because of the horrific crimes I’ve committed, my family was shattered … I didn’t realize that my sisters became very hostile toward one another. So, when I came home, we had a family get together … and it was encouraging for me to have my older sister say that me coming home is like a bridge to her getting her little sister back.73

For others, the estrangement has lingered. Howard J. noted: “Almost all my family relationships were estranged, and I am working on rebuilding the bridges I tore up.” He added: “It is an ongoing process … it’s breaking my heart, [but] I am leaving the door open, and … I am constantly trying to learn more about how to invest in relationships.”74

Judith B. said:

Family reunification is hard when you’ve been down for a long time … My son was a young teenager at the time I went to prison. Now, 28 years later, he has to … deal with a mother who is aging [and] has been suddenly released from prison.

She noted how difficult it is for children and said that “people should have compassion for [family members] with these unexpected releases.”75

Four out of five respondents said they had cared for or assisted someone sick or an older person since being released. Fifty percent of that group cared for a parent or grandparent. Tommy D.’s father, for instance, acquired a disability during an accident at work, and Tommy has since stepped in to take care of him.76

Others help people in their community. These include Paul B., who has looked out for his neighbor and assisted with daily tasks. “I care for my [older] neighbors who live alone,” said Paul. “I’ve had to go over there and pick [one of them] up off the floor. I [also] take the trash out and fix the trees.”77

The last question on the survey asked what gives people the most joy in their lives. Nearly every respondent mentioned family.78 Samuel E. told us that was an easy question to answer: “Being able to reunite with family and friends and actually doing some good.”79 Josh C. said, “What gives me the most joy is just being at home with family. We’re not doing nothing but being home and being family.”80 Dianna P. joked, “My family! Oh, absolutely my family! My cat comes in close second. His name is Mango, and he’s so darling. He’s the best cuddler.”81

Building New Ties in the Local Community

Many respondents said they built new ties in their communities through volunteering and joining local organizations. Leif T. noted:

I’ve done community and neighborhood cleanups-pull weeds, paint over graffiti, things of that nature. I’ve also volunteered at a city councilman’s office. They were putting together a jazz festival and needed a lot of help orchestrating it and setting everything up. Whatever is needed in the community, I usually step up and help out in whatever way [I can].82

The following section explores other ways this group has contributed to and engaged with their local communities.

Contributing to Community

People who have served long prison sentences can face social and cultural barriers to contributing their time and resources to the communities they return to. Nevertheless, the vast majority of respondents said they had been actively involved in their communities since being released. Ninety-four percent reported volunteering with charities, community organizations, or nonprofit organizations since release, and 98 percent said they informally helped community members who needed help. Comparatively, between September 2020 and 2021, only an estimated 18.3 percent of Californians formally volunteered with organizations and only 46.1 percent informally helped their neighbors.83 The most common forms of volunteerism among the survey respondents were mentoring, sports, or other activities with youth; assisting in food banks or otherwise helping people in poverty or experiencing houselessness; working with religious or community organizations; and volunteering in animal shelters.