The Vatican and the Chinese government are planning to renew a deal in October that they signed in 2018. That agreement, which has never been made public, is believed to give the Chinese government the power to choose bishops and the Vatican the ability to veto them.

Human Rights Watch and many others, including from within the Roman Catholic Church, have repeatedly criticized those arrangements. Even when the agreement was first signed, it was clear that China under President Xi Jinping was highly repressive, including toward religious freedom. In Xinjiang, the government has detained as many as a million Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims, surveilled the entire population, and tried to erase swaths minority culture, including razing thousands of mosques. On August 31, the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights issued a damning report substantiating these abuses, concluding that the Chinese government may have committed crimes against humanity.

Xi has steamrolled human rights throughout China, under the impetus of his feverish “China Dream.” Apparently dissatisfied with the Chinese Communist Party’s weakened grasp over the population after decades of economic growth, Xi reasserted control in the name of the “great rejuvenation” of the Chinese nation. Conveniently, he also tightened his own control over the Party bureaucracy, making himself China’s most powerful—and abusive—leader since Mao Zedong. In October, just as the Holy See will renew its agreement with the Chinese government, Xi will begin an unprecedented third term as Party general secretary.

One pillar of Xi’s “China Dream” is the government’s efforts to reorient people’s loyalties toward the Party, and thus to Xi. Those who promote alternative worldviews—such as universal human rights, faith, or spirituality—are persecuted and “reeducated.”

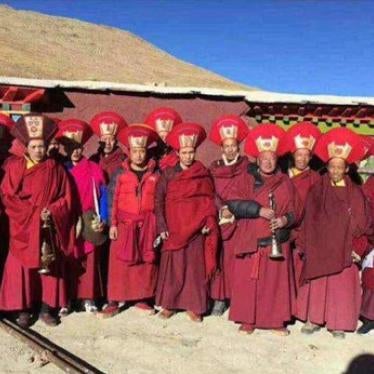

The Chinese government’s efforts to “Sinicize” religions appear to go beyond imposing escalated controls to a comprehensive reshaping of religions from Tibetan Buddhism to Catholicism. It mandates that all religious establishments in China must fly the national flag and organize flag-raising ceremonies; replace “Western” icons, architecture, and religious music with “traditional Chinese” versions; and promote “socialist core values” and Xi Jinping thought so that followers “love the motherland and obey state power.” By controlling symbols, teachings, and personnel, Beijing is fundamentally transforming these religions so that they promote allegiance—not to people’s religious beliefs—but to the Party.

Why did the Vatican choose to enter into an agreement with the Chinese government during a time of heightened religious oppression? In 2020, Pope Francis made a passing mention characterizing the Uyghurs as “persecuted,” so he evidently is aware of Beijing’s abuses. Pope Francis has praised the Vatican-China deal as “diplomacy,” and “the art of the possible,” comparing the Vatican’s outreach to China to previous Vatican efforts engaging with the Soviet Union to maintain Catholicism’s presence in the country. The Vatican may think that it will gain better access to Catholics across China. In late September, it was reported that the Vatican may soon establish a mission in Beijing.

What, then, is the Vatican’s bottom line? In May, Beijing, via the Hong Kong police, arrested Cardinal Zen, a 90-year-old advocate of human rights and democracy, who had organized a humanitarian and legal fund for arrested protesters. He was arrested for “colluding with foreign forces,” a crime under the new draconian National Security Law that carries a maximum sentence of life in prison, and also charged with the crime of failing to properly register the fund, with a maximum fine of HKD10,000 ($1,274). While the Vatican expressed “concerns” over his arrests, the Vatican secretary of state, Cardinal Pietro Parolin, said he hoped the arrest would not “complicate Vatican-China dialogue.”

The Vatican has made it chillingly clear that neither Zen’s arrest, nor the continued detention, enforced disappearance, and imprisonment of Catholic bishops and followers in China—such as the Henan bishop, Joseph Zhang Weizhu, or the Hebei bishop, Cui Tai—will sway its actions.

By renewing a secretive deal with Beijing, the Vatican is effectively endorsing the Chinese government’s perversion of religions and is dangerously close to being complicit in the country’s deepening rights abuses. But it still has time to make a U-turn: Make its China agreement public, ensure that it respects freedom of religion, and push Beijing to drop charges and investigations against Cardinal Zen and to free bishops Zhang Weizhu and Cui Tai. If its Catholic brothers and sisters in China have managed to persist in standing for justice and human rights despite decades of persecution, the Vatican can surely find the moral courage to defend them.