In February 2020, the foreign ministers of the Holy See and China met in their highest-level official encounter in decades. Their agenda included the September 2018 provisional agreement that allows the Vatican to appoint bishops pre-approved by Chinese authorities.

The agreement, details of which have not been made public, ended a decades-long standoff over who has the authority to appoint bishops in China. China’s estimated 12 million Catholics have been divided between an underground community that pledges allegiance to the pope and a government-run association, the Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association. Under the accord, Beijing proposes names for future bishops, and the pope has veto power over those appointments.

Some leaders of the Chinese underground church who endured decades of persecution for refusing to join the Patriotic Association felt they had been betrayed, said Joseph Zen, the retired cardinal of Hong Kong and a critic of the Chinese government. Zen accused the Vatican of “selling out the Catholic church in China.”

The Chinese government restricts religious practice to five officially recognized religions in officially approved premises. Authorities retain control over religious bodies’ personnel appointments, publications, finances, and seminary applications. The government classifies many religious groups outside its control as “evil cults” and subjects members to police harassment, torture, arbitrary detention, and imprisonment.

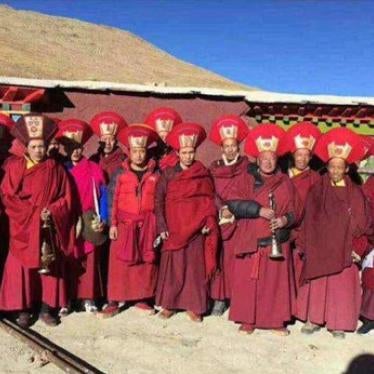

Authorities in recent years have demolished hundreds of church buildings or the crosses atop them, prevented believers from gathering in house churches, confiscated Bibles and other religious materials, and banned online Bible sales. The government has also imposed unprecedented control over religious practices in the predominantly Muslim region of Xinjiang and over Buddhism in Tibetan areas.

To improve the Vatican’s relationship with Beijing, Pope Francis since his election has sent gifts to Chinese President Xi Jinping, dispatched 40 artworks to Beijing in a cultural exchange, and praised China’s “great commitment” to contain the coronavirus outbreak. Despite his call on world leaders to “place human rights at the heart of all policies” and in contrast to his vocal criticism of Western governments’ border control policies, the pope has kept mum on the Chinese government’s serious human rights abuses, including the persecution of Christians and other religious groups across China and the severe repression in Xinjiang. Many Catholics in Hong Kong have urged him to mention the protests there, but Francis has avoided doing so.

Pope Francis’ silence is particularly troubling as Beijing intensified repression on religious freedom in China.

In 2018, Chinese authorities revised the Regulations on Religious Affairs. Designed to “curb extremism” and “resist infiltration,” it bans unauthorized teaching about religion and going abroad to take part in training or meetings. In a speech in March 2019, Xu Xiaohong, the official who oversees state-sanctioned Christian churches, called on churches to purge Western influence and to further “Sinicize” the religion: “[We] must recognize that Chinese churches are surnamed ‘China,’ not ‘the West.’” In September, a state-sanctioned church in Henan province was ordered to replace the Ten Commandments with quotes from President Xi.

In February, Measures on the Management of Religious Groups, promulgated by China’s State Administration for Religious Affairs, went into effect. It further tightened party control over religion by requiring that “religious groups must uphold the Chinese Communist Party’s leadership…uphold the Sinicization of religions in China” and “implement socialistic core values.”

And Chinese authorities have shown no particular mercy towards Catholic clergy since the 2018 China-Holy See agreement, harassing and forcibly disappearing some of those who remain loyal to the pope. In November 2018, authorities disappeared Bishop Shao Zhumin of Wenzhou Diocese in Zhejiang province for at least a week. In November 2019, police detained Guo Xijin, a former bishop in Fujian province, after he refused to bring his church under the government-run Patriotic Catholic Association. In December, Guo fled state custody and went into hiding. Before the signing of the agreement, the Vatican had asked Guo to step aside in favor of Chinese government-appointed bishops.

Authorities in Guo’s diocese of Mindong have also closed down churches, installed surveillance cameras outside, and evicted priests who refused to sign agreements to be brought under official control.

Clearly little has improved for millions of Catholics in China. Shortly after the signing of the 2018 agreement, You Jingyou, a human rights activist and member of an “underground” Catholic church in Fujian province, expressed his concerns: “In the future, I’m afraid that Chinese Catholics might think singing the praises of the Communist Party is an integral part of the Catholic faith.”

If Pope Francis doesn’t want to see this happen, he should speak out against China’s religious persecution.