Summary

“Offenders must be punished hard and swiftly, public security and cultural market administrations must investigate and prosecute them with awesome power.”

— Dong Yunhu, former head of the Tibet Autonomous Region Propaganda Bureau, Tibet Autonomous Region meeting “to promote striking down and clearing up infiltration of reactionary Tibet Independence propaganda,” February 2, 2015

In late August or early September 2019, Choegyal Wangpo, a 46-year-old monk from Tengdro monastery in Tingri county in the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR), mistakenly left his cellphone in a café while visiting Lhasa, the regional capital. The café owner gave the phone to police, who found messages between Choegyal Wangpo and other Tibetans originally from his area of Tingri now living in Nepal, where they had established a monastery. The messages showed that Choegyal Wangpo had sent a donation from Tengdro monastery to help those Tibetans and their community to recover from the April 2015 earthquake that caused widespread devastation across Nepal.

Lhasa police immediately detained Choegyal Wangpo, reportedly beat him severely, and interrogated him.

This detention set in motion a chain of events: a contingent of police and other security forces traveled from Lhasa to Choegyal Wangpo’s home village of Dranak, and raided the village and adjoining monastery of Tengdro. During the night raid, police severely beat a number of Tengdro monks and villagers, and detained about 20 of them. Like Choegyal Wangpo, they are believed to have been held on suspicion of having exchanged messages with other Tibetans abroad, of having contributed to the earthquake relief sent to Tibetans at the sister monastery in Nepal, or of having possessed photographs or literature related to the Dalai Lama.

Police then began interrogating all the Tengdro monks, and a team of cadres—government or Chinese Communist Party officials—began holding daily political education sessions with monks from the monastery and village residents. Three days after the police raid on the village and the monastery, Lobsang Zoepa, a monk at Tengdro monastery and a resident of Dranak, committed suicide in apparent protest against the authorities’ treatment of his family and community. Shortly after Lobsang Zoepa’s suicide, internet connections to the village were cut off.

Sources told Human Rights Watch that most of the 20 monks detained in or just after the raid, including monks Ngawang Samten, 50, Lobsang, 36, and Nyima Tenzin, 43, were held without trial for several months in the nearby Tingri county town. These detainees are believed to have been released after making pledges not to carry out any political acts, but were not allowed to rejoin the monastery.

Three other Tengdro monastery monks were not released: Lobsang Jinpa, 43, deputy head of the monastery; Ngawang Yeshe, 36, who was detained during the September 4 night raid; and Norbu Dondrub, 64, chaplain or caretaker at the monastery and the third most senior of the monks, who was detained one month later. These monks were held for the following year in Nyari prison near Shigatse, the municipal seat that oversees Tingri, together with Choegyal Wangpo.

In September 2020, the Shigatse Intermediate People’s Court tried the four monks in secret on unknown charges. They were found guilty and given extraordinarily harsh sentences: the court sentenced Choegyal Wangpo to 20 years in prison; Lobsang Jinpa received a 19-year sentence; and Norbu Dondrub, who had sustained critical injuries from beatings by police, was given a 17-year sentence. Ngawang Yeshe was sentenced to 5 years in prison.

This report provides the first detailed account of the raid on the Tengdro monastery and its consequences, including multiple detentions and a suicide, that has appeared in any media within or outside China. It also provides analysis of what the case shows about conditions in Tibet today and assesses possible reasons for the unprecedentedly harsh sentences given to three of the four monks for minor online activities and communications that are commonplace among Tibetans. Human Rights Watch has not been able to find another case in which Tibetans were convicted of major offenses and sentenced to such long terms without any information emerging to explain the severity of the punishment.

The defendants included older monks in a remote rural location who had no previous history of protest or activism and who were unlikely to have been involved in prohibited political activity without any sign of it being known to their community. In previous cases of Tibetans convicted for political activities, those activities were either known to the community or police, and local officials informally disclosed some information on the accusations to retain credibility within the local community and to avoid the perception of random persecution. In this case, no reports have come to light indicating any political or dissident activity by the monks apart from routine misdemeanors, such as possessing pictures of the Dalai Lama on their phones and exchanging messages with Tibetans overseas, with no indication of any purpose considered subversive.

The information available about the Tengdro case strongly suggests that the defendants had not taken part in any significant criminal activity, even as defined within Chinese law. While Tibetans in Tibet often avoid making politically sensitive remarks, they routinely communicate with people in other countries by phone or text message, and no Chinese laws currently forbid this. Sending funds abroad, also present in this case, is likely to be monitored but is not illegal in China unless it includes a specific offense such as fraud, contact with an illegal organization, encouraging separatism, or espionage, none of which appear to have been involved in this case.

Even if authorities had considered the monks guilty of such offenses, the harsh sentences would be unprecedented. Chinese courts usually impose extreme sentences only for recidivism, or for involvement in activities such as organizing protests, illegal organizations, espionage, acts of violence, or, increasingly, spreading unofficial news. Yet, there is no suggestion that any of the Tengdro monks had previous convictions or had taken part in such activities.

This is not the first case in Tingri county involving extreme punishment of Tibetans for minor or invented offenses; sentences in an earlier case, detailed below, also have not previously been reported. It involved a minor incident in May 2008 in the monastery of Shelkar Choede, in the county town. In that incident twelve monks were arrested following a disagreement with local cadres who had demanded that the monks denounce the Dalai Lama during a political education session. According to information obtained from sources in the area, two monks, Tenzin Gepel and Khyenrab Nyima, received 17- and 15-year sentences, respectively, simply for arguing with the cadres during the education session.

In this earlier case, the monks’ refusal to denounce the Dalai Lama was considered by the authorities, who were carrying out a crackdown following a wave of protest in the region two months earlier, to be “inciting separatism” and therefore viewed as criminal. Nevertheless, the sentencing of Tenzin Gepel and Khyenrab Nyima was extraordinarily harsh given the nature of their actions and shares several features with the Tengdro case.

While Human Rights Watch cannot provide a definitive explanation for the sentences in the Tengdro case because of restrictions on information from Tibet, we believe that the exceptionally severe sentences reflect increasing pressures on Chinese bureaucrats to find and punish cases of political subversion, even if the alleged subversion is a figment of the officials’ minds.

These pressures include the authorities’ major new emphasis on preventive control, particularly in minority areas: officials have been ordered to apply the principle of preemptive security in all aspects of their work, meaning the identification of potential culprits before they carry out a criminal action. This principle has been demonstrated in its most extreme form by the practice of mass detentions of Turkic Muslims in the Xinjiang region.

The Tengdro case appears to be an example of preventive control in the Tibetan context: the severity of the sentences coupled with the absence of information suggesting any serious criminal or political activity by the monks (present in nearly all other cases in which authorities imposed comparable sentences), is hard to explain otherwise.

These pressures toward preemptive action may have been exacerbated in the Tengdro case because of the number of agencies within the Chinese bureaucracy involved. Particularly in locations such as Tibet and Xinjiang, security is not an issue limited to officials in public security or national security departments: all cadres at every level and in every agency have the responsibility to identify and counter threats to national security and social stability. In addition, the Tengdro case involved overlapping areas of policy and administration: officials from numerous departments would have been involved in the case, including, among others, the Public Security Bureau, the State Security Bureau, the United Front Work Department, the Religious Affairs Bureau, the TAR Internet Affairs Office, and the Internet Management Department within the Public Security Bureau.

Those agencies include officials responsible for managing online communications, whose work in Tibet focuses on preventing unapproved information, such as speeches by the Dalai Lama, being brought or sent into Tibet by Tibetans from abroad. Additionally, as incomes have risen rapidly in Tibet, security and financial officials there are now required to monitor funding transfers between Tibetans, with recent regulations banning Tibetans from sending donations to projects associated with the Dalai Lama or his Tibetan government-in-exile. Those officials have become increasingly likely to interpret innocent exchanges of funds or messages between Tibetans inside and outside China as support for exile activists, and thus as political conspiracies against China.

The accusations against the Tengdro monks also put pressure on officials responsible for the management of monasteries, viewed by Chinese leaders as the key sites of potential unrest in Tibet. Although the number of protests in Tibet by monks or others has dropped sharply in the last decade, officials at all levels are required increasingly to demonstrate their commitment to imposing rigorous control over monasteries in their areas. Officials responsible for religious management in Tingri will have been eager to compensate for suspicions that they had failed to monitor the Tengdro monks.

Officials responsible for security in Tingri faced additional demands because the area is close to China’s border with Nepal, and a significant number of Tibetans fled from there in the 1950s and again from the 1980s till 2008, when border controls were stepped up. In 2017, China’s leader Xi Jinping called for a drive to accelerate security operations and development in Tibet’s border areas. Since then, officials in areas such as Tingri now have to show maximal achievements in mobilizing security operations in their areas, specifically to detect supposed infiltration by followers of the Dalai Lama. These officials also had reasons to protect themselves by responding harshly to the Tengdro case.

This situation was compounded by the fact that it was police in Lhasa who by chance discovered messages with exiles on Choegyal Wangpo’s phone. Instead of transferring the case to local authorities, the Lhasa police treated the case as a provincial-level incident and themselves carried out the raid on the monastery and village. Local officials would have put their careers at risk if they had contested higher-level rulings from Lhasa about the case, and would have themselves risked punishment if they had failed to demonstrate exceptional diligence to compensate for their not having already identified the case.

These factors in the Tengdro case appear to have combined to form a “perfect storm” in which officials from multiple governmental and Communist Party agencies sought to protect themselves from punishment or to increase their chances of promotion. This appears to have resulted in exaggerated accusations against the monks and extreme sentences, with little regard to the evidence in the case, illustrating the way in which steadily accumulating pressures and incentives within the Chinese bureaucracy lead to serious abuses of human rights and miscarriages of justice.

Human Rights Watch urges that the verdicts against the four monks from Tengdro and the two from Shelkar Choede be quashed immediately, and that the reported beatings and suicide be investigated by independent authorities.

Recommendations

To the Chinese Government

- Quash the sentences imposed on the four monks from Tengdro monastery and the two monks from Shelkar Choede, and unconditionally release them from detention;

- Investigate publicly and appropriately prosecute all officials responsible for the beatings of monks and others in connection with the detention of Choegyal Wangpo in Lhasa and the raid on Dranak village in Tingri;

- Impartially investigate publicly the circumstances that led to the suicide of Lobsang Zoepa, and appropriate prosecute any officials responsible for harassment or other offenses against him or his family members;

- End required attendance at, and participation in, political education meetings;

- End the practice of holding trials in secret and not publishing trial proceedings involving Tibetans in the TAR accused of jeopardizing state security;

- Permit the clergy in Tibet to appoint their own leadership and engage in religious activities consistent with the right to freedom of religion and belief;

- End restrictions on Tibetans and others to communicate freely with others, including those abroad, consistent with the right to freedom of expression;

- End prosecutions of people for exercising their rights and fundamental freedoms protected under international human rights law; and

- Create an independent, credible, and impartial judiciary.

To the United Nations

- The UN Human Rights Council should urge the Chinese government to release the Tengdro monks;

- The Human Rights Council should also establish, as suggested by the 50 Special Procedures mandate holders in June 2020, “an impartial and independent United Nations mechanism…to closely monitor, analyse and report annually on the human rights situation in China, particularly, in view of the urgency of the situations in the Hong Kong SAR, the Xinjiang Autonomous Region and the Tibet Autonomous Region;”

- The UN high commissioner for human rights should call on the Chinese government to end prosecutions and sentencing of Tibetans in violation of their fundamental rights; and

- UN special procedures and treaty bodies should continue to document and publicly report on human rights violations in Tibetan areas by the Chinese authorities.

To Concerned Governments in Coordinated Bilateral or Multilateral Action

- Call for the immediate and unconditional release of the Tengdro monks;

- Consider imposing targeted individual sanctions on officials responsible for human rights violations in the TAR; and

- Support the call for a standing China mandate at the United Nations.

To the Nepalese Government

- Allow Tibetans to safely cross the border and ensure that they have access to the asylum process.

To WeChat

- Uphold responsibility to respect the human rights of people who use the platform, including their right to freedom of expression and privacy, consistent with the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. This includes not restricting access to content and not monitoring or otherwise sharing data over to authorities, consistent with international standards; and

- Do not allow the TAR Public Security Bureau’s Internet Management Department to manage WeChat communications.

Methodology

The Chinese government is hostile to research by international human rights organizations, closely monitors and strictly limits the activities of domestic civil society groups, and censors the internet, media, and communications between individuals, especially those involving foreigners. Over the past several years, the government has significantly increased surveillance and suppression of discussions and activism about many aspects of society. The courts have handed down lengthy prison sentences to Tibetans and others accused of sending unofficial information within their community, as well as abroad.

As a result, to protect potential sources, the research drew heavily on interviews with individuals outside China who have detailed knowledge of the events described in the report. The individuals asked to remain anonymous to protect themselves and others from Chinese government reprisal. Human Rights Watch interviewed these sources independently and repeatedly, and cross-checked their information against each other and against previous records of interviews conducted with third parties. These accounts and information provided by different people separately matched in nearly all particulars. Human Rights Watch was also provided with a video directly substantiating a key part of the report, but is unable to make it public without putting certain individuals at risk.

Supporting documentation discussing related cases, policies, and inspection visits by cadres comes from Chinese state media. Included in these articles and government documents were statements that confirm, indirectly, that a serious security incident took place at Tengdro monastery at or around the time reported by our sources. These documents also provided much of the basis for our analysis of the probable reasons for the extreme sentences imposed on the monks. Although we have based our analysis on our study of this documentation and the information from our sources, the lack of direct accounts of events and of access to the region means that it necessarily remains speculative.

In references to earlier cases of detention or sentencing for political offenses, the report draws, in some cases, on reports by exile and foreign media, and occasionally on reports by other nongovernmental organizations.

Human Rights Watch also searched a national database of court verdicts seeking information on the cases addressed here, but to no avail. This is not surprising: to our knowledge, no cases from the TAR involving alleged endangerment of state security have been included in court records and court videos that are now publicly available in China.[1] In the past decade, no court cases of this type involving Tibetans in the TAR have been reported in the official Chinese media.

Background

Tengdro Monastery and the Surrounding Community

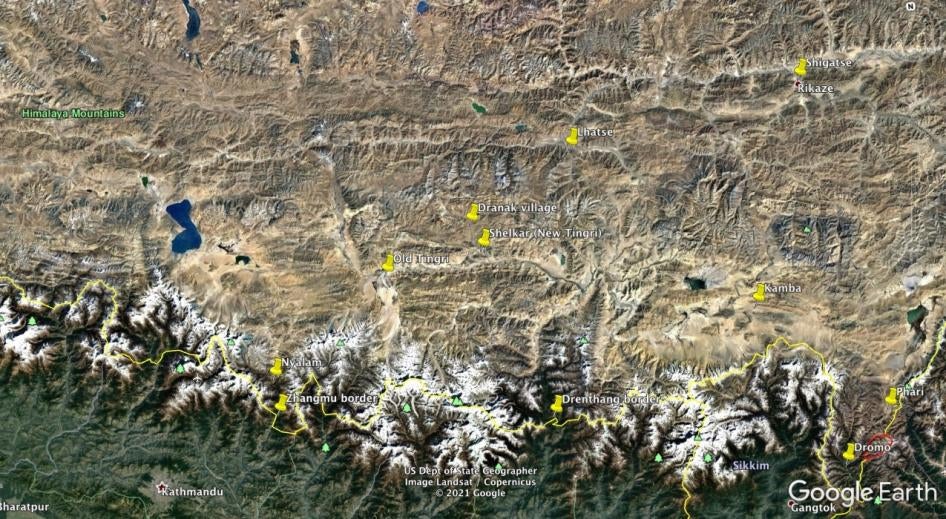

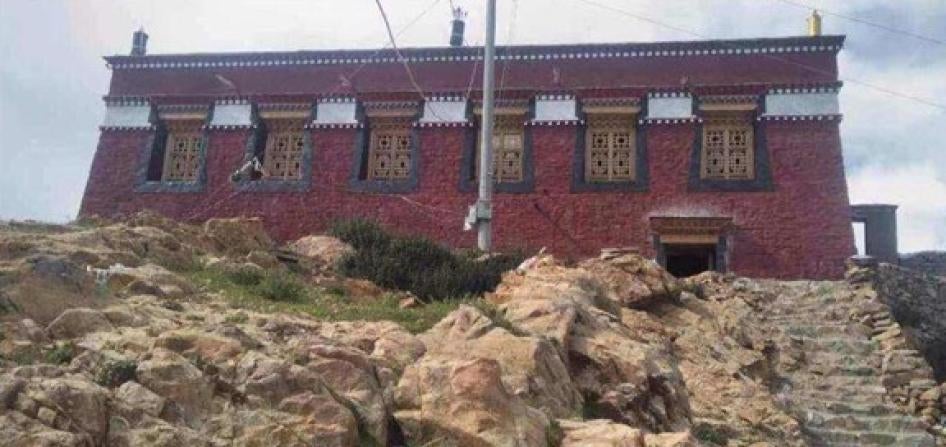

The monastery of Tengdro (Ch.: Dangzhuosi, 当卓寺) is situated in the Gyalnor valley, just to the north of the sacred mountain of Tsibri (“Ribbed Mountain”), in what is now known as Tingri county. The monastery overlooks Dranak village (Ch.: Chanacun, 查那村) and is 12 kilometers north of Shelkar town, now known as New Tingri, the location of the administrative seat of Tingri county.

Tashi Tengdro monastery was founded in 1235 by a legendary Buddhist teacher, Götsangpa Gonpo Dorje (1189-1258). The monks at Tengdro belong to the Drukpa Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism and, as used to be common in that school, wear monastic robes but are married, non-celibate householders. They carry out extensive religious rituals and studies in the monastery, but live in their own homes in the nearby village. Monks of this type are known in Tibetan as “serkhyimpa” (literally “yellow[-robed] householders”) or “ngakpa.”

The main lama or teacher associated with the monastery, the 5th Sengdrak Rinpoche (1947-2005), a distinguished teacher in the Drukpa Kagyu tradition, fled from Tibet to Nepal in 1960, shortly after China’s annexation of Tibet. He established an exile monastery in Nepal in 1976, and in 1988 established a retreat community at Liping, next to the border crossing between Nepal and China at Kodari.

In 1960, as occurred with almost all monasteries in Tibet, Tengdro monastery was destroyed in the wave of violence that followed Mao’s call for “democratic reforms.” It remained abandoned for the following 20 years, during most of which time religious practice was banned throughout Tibet.

After the “reform and opening up” era—launched nationwide in 1979—began in Tibet in the 1980s, local residents began basic restoration of the monastery, and in 1993, Sengdrak Rinpoche was allowed to make a brief visit to the monasteries in his home area.[2] However, this was the only time he was allowed to visit: in the later 1990s and 2000s, policies became more restrictive in Tibet generally. Tensions increased in the Tingri area, partly because of the steady intensification of border security. Tingri is on the principal route taken by Tibetans escaping to India via Nepal.[3]

By 2017, the community in Dranak was able to collect sufficient donations to carry out extensive rebuilding of the assembly hall and other buildings at Tengdro. Although new monasteries are rarely if ever allowed in Tibet—the state declared in 1991 that the existing “venues for religious activities … have basically satisfied the necessities of the normal religious activities of the masses who believe in religion”—monasteries destroyed in the Maoist era may be reconstructed if official approval has been obtained. [4] The Tengdro monks had been able to get such approval, a sure sign that they had a record of good conduct in recent decades and had good relations with local officials.

After the restoration of the monastery, there were nearly 30 monks, all householders, at Tengdro. As part of the approval process, the monks and villagers established an officially required and approved “temple management committee” for the monastery. Choegyal Wangpo was appointed by the local Religious Affairs Bureau as the official zhuren or leader of that committee, and Lobsang Jinpa was appointed as its deputy leader.

In the same year, the Tengdro community constructed an open-air statue of the 8th century Buddhist saint Guru Rinpoche, known as Padmasambhava in Sanskrit, and his two consorts. The statue overlooks the valley from a prominent position on the mountainside near the monastery. The erection of religious statues is illegal without prior government permission and a partially constructed giant statue of Guru Rinpoche in the same form—known as “overwhelming the conditioned world with splendor”—was demolished by officials at the Samye monastery, Lhokha municipality, TAR, in May 2007.[5] A similar statue in Darchen, Ngari prefecture, TAR, was removed by officials in September that year.[6] However, local government officials carried out inspections of the statue at Tengdro prior to the 2019 raid and, according to sources interviewed by Human Rights Watch, had given approval for the construction of the statue.

The village of Dranak, literally “black crag,” consists of 24 households. It is one of 29 villages under the jurisdiction of Shelkar town (zhen), which had an overall population of 11,500 in 2017. Located at 4,300 meters (14,100 feet) above sea level, Shelkar is prominent as a base for tourists and climbers travelling to or from Everest Base Camp, less than 60 kilometers directly south, or about 150 kilometers by road. The town includes the prominent Gelugpa monastery of Shelkar Choede, founded in 1385, which had nearly 300 monks before it too was destroyed in the wake of the 1960 “democratic reforms.” Reconstruction of the Shelkar Choede monastery was completed in 1993, and it now has approximately 40 monks.

Inspecting the Village: Official Visits to Dranak

Before 2011, villages and village-level monasteries in the TAR would rarely have been visited by state officials except on occasional inspection tours. That year, however, two major and unprecedented changes took place in China’s administration of communities at the grassroots level.

The first change involved the management of villages: from March 1 that year, teams of cadres were sent to live in each village in the TAR. The first batch of 10,000 cadres was sent in teams of four or more to live in 1,000 villages to “deepen their bonds with the masses” and to educate them in the core message of “oppose separatism, safeguard stability and promote development.”[7] One of the first of these village-resident cadre teams was sent to Gangkar town (known as Old Tingri), 60 kilometers west of Shelkar. In October 2011, state media announced that teams were being sent to all 5,423 villages in the TAR. The program, initially launched for three years, continues to the present.[8]

It is not clear when a resident cadre team was first stationed in Dranak. As in most Chinese villages, Dranak had, or soon came to have, two committees composed of local residents—the “village committee” and the “village Party committee.” An official social media post in October 2018 describes members of the two committees at Dranak attending two film screenings showing authorities’ success in carrying out “poverty alleviation” throughout the country. The screenings were followed by discussions organized and led by the “Xiege’er [Shelkar] Township Village-resident Work Team in Chana Village” (zhucun gongzuozu), which was promoting the films as part of its propaganda tasks. [9] This confirms that a cadre team had been installed in Dranak village by that time, if not much earlier. Village-based cadre teams would have been intensively monitoring all villagers and even spending time living with them from at least a year before the police raid on Tengdro monastery.

The second major change in administration in Tibet involved monasteries. In October 2011, monastery-resident cadre teams known in Chinese as zhusi gongzuozu were installed permanently at each monastery at township-level or above in the TAR.[10] Tengdro was probably classified as a village-level monastery and so may not have needed to host a permanent resident cadre team, but it seems at least to have had to prepare accommodation for cadres from outside the village: in 2012, the Tingri county government published a call for construction companies to submit bids for building a house to be used by the “temple management committee” at Tengdro monastery, which is unlikely to have been needed if the committee members were all from the monastery or the village.[11] Some of the cadres who used this house might have been occasional visitors rather than permanent residents, but they appear to have been residing at the monastery by at least August 2018, when an official report refers to meetings with the temple management committee at Tengdro and with “cadres stationed in the temple.”[12]

The same report also notes that by that date, police had been stationed at the monastery. The presence of police at village-level, let alone within a village-level monastery, is a new development in Tibet, where, until recently, police have been stationed only at township level or above.[13]

In addition, from 2011 onwards, senior officials conducted several inspections of the village and monastery. These inspections are important because they appear to confirm claims by sources connected to the village that the reconstruction of the monastery in 2017, the erection of the outdoor statue, and the religious activities at the monastery were well known to local officials and had been approved by them.

All of the known inspections were led by ethnic Chinese cadres, at least one of whom was high-level: Liu Hanlin, a senior regional-level government official who visited the village in early September 2013. He was the political commissar of the fire-fighting wing of the TAR Public Security Bureau, and his task was to carry out a “research and investigation visit” to Dranak. Ostensibly, his purpose was to carry out a policy known as “pairing” (also referred to as “pair-housing” or “pairing and assistance”), which requires government and Party officials at all levels to visit and present gifts to at least one family officially listed as impoverished. Liu was also tasked with “studying the villager’s production and living conditions on the spot” and was expected to help them with any practical problems. The official account describes Liu visiting individual houses and giving his own money to help impoverished residents, together with his phone number in case they needed to contact him. But he would certainly have been inspecting the legal and political situation as well.

There must have been other officials living in or visiting the monastery in 2014, because that December, the main newspaper in Tibet, Tibet Daily (Xizang ribao), announced that one of the Tengdro monks—Ngawang Yeshe— had been given a regional-level award by the TAR authorities as one of the region’s “Law-abiding Advanced Monks and Nuns.”[14] This is almost certainly the same Ngawang Yeshe who would be sentenced to five years in prison in 2020.

In January 2017, the deputy head of the county fire service, Tong Yun, visited the monastery to convey greetings for the New Year and to carry out the “pairing” work that had led Tengdro to be allocated to the fire service as one of its “pairs” in the Tibetan countryside. To show his generosity in “pairing” with the monastery, Tong gave gifts of cooking oil, tea, and sacks of rice to the monks, and gave instructions on fire safety.[15] As with the other visits, there is no suggestion in media coverage that Chinese officials found or had expected to find any problem in the village or had any criticism of the Tengdro monks.

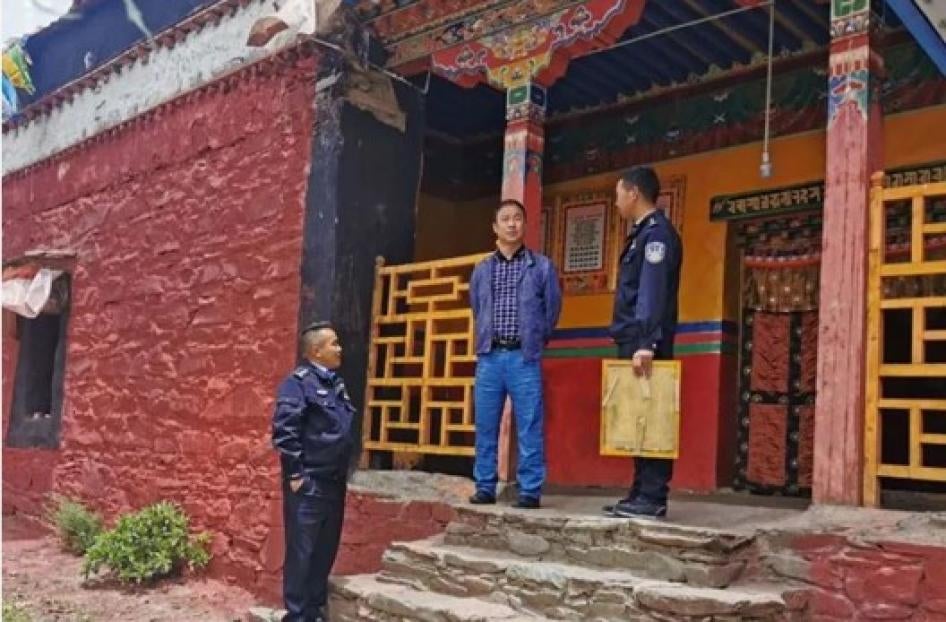

In August 2018, another official, Hu Jicheng, secretary of the Tingri County Political-Legal Committee and head of the county’s Public Security Bureau, carried out an inspection tour of local monasteries.[16] According to an official media report, Hu “went deep into the temples” in the county that month to “firmly ensure the continued stability of the religious field in Tingri county.” His aim, according to an official media report, was to ensure that the management teams in each monastery were “educating and guiding” monks so that the majority would have a “correct world outlook” and would “congratulate the Party, listen to the Party, and follow the Party.”[17]

As part of his tour, Hu visited Tengdro and Shelkar Choede monasteries. He arrived on August 5 and focused on “the recent temple management committees and the police stationed in the temples.”[18] He listened to reports from the local officials and then gave lengthy instructions to the committees, the resident cadres, and the monastery police at both monasteries: they were to “understand the situation from a high level of ideology,” “unify their thoughts and actions with those of the regional, municipality, and county [committees],” “implement the various temple management and control measures,” and “increase the intensity of the education and management of monks and nuns.” Reflecting ever increasing pressures from Lhasa to intensify controls on monks and monasteries throughout Tibet, Hu ordered the temple management cadres and police to hold an education session with the monks each week. The sessions were needed, Hu said, in order to make the monks “deeply understand the spirit of General Secretary Xi Jinping’s important speech to adapt religion to socialist society” and to ensure “that the majority of monks and nuns can fully understand ‘unity and stability are a blessing, secession and turmoil are a curse.’”[19]

Hu also ordered the officials to carry out rehearsal drills for dealing with “various major events and emergencies that may occur in the temples and religious fields to ensure that emergency events can be handled efficiently and securely in accordance with the law,” probably a reference to political protests or dissent.[20] These were, however, standard procedures across Tibet at that time, and again, reflected the steadily increasing pressure on officials to enforce strict security and political compliance in Tibetan monasteries. There were no indications in these reports of any criticism of the monks.

On at least one occasion, county police seem to have gone out of their way to be helpful to the Tengdro monks on at least one occasion: on August 4, 2019, they arranged for eight policemen to help direct the traffic and organize parking during celebration of the annual religious festival of Choekor Du-chen.[21] The police reported that at least 80 vehicles and a large number of motorcycles brought worshippers from outside the village to the monastery for the festival that day. One photograph issued by the county police shows 130 people gathered outside the monastery during the event, wearing greeting scarves and gathered around a prayer-flagpole—strong indicators of the monastery’s local importance as an active religious center.

These reports, fragmentary though they are, indicate that the Tengdro monks were in good standing with state officials and the police up to at least the month before the night raid in September 2019. They also show that at least one Tengdro monk had been publicly praised throughout the TAR as a model and law-abiding monk. There is no hint in these reports that, exactly one month after the traffic police helped with the running of the festival, police from the Tibetan capital would raid the village and the monastery, that monks and villagers would be beaten and arrested, and that the three leading members of the monastery would receive sentences of unprecedented length.

I. The Raid and its Aftermath

In late August or early September 2019, shortly after the conclusion of the Choekor Du-chen festival at Tengdro monastery, Choegyal Wangpo drove to Lhasa, the capital of the TAR. He had been appointed some years earlier as the zhuren, or leader, of the monastery by the county Religious Affairs Bureau. Like the rest of the 30 or more monks at the monastery, he was a serkhyimpa, or householder-monk, and he lived with his wife and children in the village. His reason for making the 500-kilometer journey to Lhasa was in part to give driving practice to his two sons, who were both learning to drive.

During their stay in Lhasa, Choegyal Wangpo left his cell phone by mistake in a restaurant or café, and the owner of the café handed the phone to the police. The police were able to obtain access to the phone, on which they found details of Choegyal Wangpo’s contacts abroad, photographs of the Dalai Lama, and messages exchanged with Tibetans from Tingri who are now living in Nepal and India.

Among the messages were notifications that Choegyal Wangpo had sent funds to some of these Tibetans abroad, including various types of religious offerings. The offerings included significant donations to the monastery founded by Sengdrak Rinpoche in Nepal. These donations had been sent to help the monastery and community recover from the severe damage caused by the 7.8-magnitude earthquake that hit areas of northern Nepal on April 25, 2015.

The Lhasa police immediately detained Choegyal Wangpo and subjected him to interrogation. According to sources with knowledge of the events, the police severely beat him during the interrogation process. The same sources reported that police appear to have been particularly concerned about the donations he had sent to Tengdro’s sister monastery in Nepal.

Police from Lhasa then travelled to Dranak village. At about 1 a.m. on the night of September 4, the police, accompanied by personnel later described by local residents as soldiers, launched a raid on the village and the monastery. The raid focused on the 20 houses in the village belonging to families whose members included a monk enrolled at Tengdro monastery. Police and soldiers wearing masks searched each of the 20 houses, confiscating photographs of the Dalai Lama, religious texts or literature related to the Dalai Lama, and religious texts purchased from Nepal or India. During the raid, the security forces beat up many of the monks, including one called Lobsang Zoepa, who was in his 60s. The four households in the village that did not include monks from the monastery were not raided.

The security forces searched the monastery, including its assembly hall, kitchen, and other rooms. There they also confiscated photographs or texts related to the Dalai Lama and seized religious texts produced in Nepal or India. During the search, the authorities severely beat Norbu Dondrup, a 64-year-old monk who served as the kunyer or chaplain in charge of the upkeep of the monastery temple.

The following day, police began interrogations of all the Tengdro monks and confiscated and searched their phones. Those whom they considered to be most at fault—apparently because they had exchanged messages on their phones with Tibetans abroad or had photographs or texts relating to the Dalai Lama—were given further beatings. Lobsang Zoepa was beaten again.

That day, following the interrogations, police detained two of the monks as principal suspects—Lobsang Jinpa, 43, deputy leader of the monastery committee, and Ngawang Yeshe, 36. The two monks were taken to Nyari prison, a municipal-level detention center in Shigatse, about 230 kilometers by road from Dranak, where Choegyal Wangpo was also held. A month later, the third most senior monk at the monastery, the chaplain Norbu Dondrup, was also detained and taken to Nyari prison. The four monks would remain there for the following year.

In Dranak, also on September 5, police detained approximately 20 other monks and at least one nun from the village. These detainees were taken to the detention center in Shelkar, the county seat. Among them were the monks Ngawang Samten, 50; Lobsang, 36; and Nyima Tenzin, 43. They were held there for several months and then released without charge, but were forbidden to rejoin any monastery. Also detained on September 5 and taken to the detention center in Shelkar were Tenzin Yeshe, a Tengdro monk, 20, and a nun, Tsewang Lhamo, approximately 25. These two detainees were released on compassionate grounds later that same week. The names of other monastery members who were detained and have since been released are not known.

A year later, around September 2020, after a year in custody, the four monks who were held at Nyari prison were tried at the Shigatse City Intermediate People’s Court. The court sentenced Choegyal Wangpo to 20 years in prison, Lobsang Jinpa to 19 years, Norbu Dondrub to 17 years, and Ngawang Yeshe to 5 years in prison.

The trial was held in secret and no record of it exists in China’s public database of trials and judgments,[22] or on the official website containing videos of trials from that court.[23] Neither was the case referred to by any media in China. Human Rights Watch has found no evidence that sentencing documents were issued to the defendants’ families, or that the defendants were allowed independent legal advice or representation in the court. As a result, the charges against the four monks and the evidence against them are not known. They are believed to have been accused of having exchanged messages with fellow-Tibetans abroad or of having possessed photographs or literature related to the Dalai Lama, and in particular of having sent donations to members of the community’s sister monastery in Nepal.

Shortly after conviction, the authorities transferred the four men from Nyari prison to a regional-level prison near Lhasa, where they are serving their sentences.

The Suicide of Lobsang Zoepa

Immediately after the raid, a team of cadres began holding daily political education sessions with monks from the monastery and the village residents. The education sessions focused initially on “Loving the Nation, Loving Religion” and on “opposing separatism.” During the sessions, the cadres made statements denouncing the Dalai Lama.

Three days later, at 8 a.m. on September 7, 2019, just an hour before the daily political education meeting was due to start, the Tengdro monk Lobsang Zoepa took his own life. It is not known how he died or whether he left a note, but his death appears to have been a protest against the treatment by police and cadres of his fellow monks, family members, and other villagers. Close contacts say that Lobsang Zoepa, besides being beaten during both the raid and then during interrogation, had been forced along with other villagers and

monks to attend the daily political education sessions meetings following the raid. These contacts also reported that cadres had shouted at and abused Lobsang Zoepa during those meetings.

Lobsang Zoepa’s adult son and one of his daughters had both been beaten during the raid and then detained. The son, Tenzin Yeshe, 20, a householder-monk at Tengdro, had been detained because the police found unapproved images and texts on his phone, which he had shared with others. The daughter, Tsewang Lhamo, about 25, had been a nun at Shabten Lhakhang, a shedra or monastic academy in the neighboring county of Sakya, about 50 kilometers northeast of Dranak. She had been among some 70 nuns whom local officials expelled between 2016 and 2019 from nunneries in Sakya either because they failed to meet political education requirements or, as in her case, because of regulations banning Tibetan monks and nuns from enrolling in a monastery outside their home area. Once expelled, monks and nuns are not usually allowed to join any other monastic institution. Tsewang Lhamo is believed to have been detained on September 5, because her phone was found to contain messages with Tibetans abroad or photographs of the Dalai Lama.

Lobsang Zoepa had been a monk at Tengdro monastery for some 30 years. He had attended a government school in the nearby town of Shelkar for at least four years in the late 1970s before leaving to work on the family’s fields once the commune system had ended. The temple at Tengdro had been gradually rebuilt in the 1980s following its destruction during the 1960s, and he had been active from the outset in the reconstruction efforts. Once he became a householder-monk himself, he studied the liturgy, became proficient in the monastic dance rituals, and carried out other aspects of monastic life. He was known for his conscientiousness in keeping the temple clean, getting up early to prepare tea for the monk’s ceremonies, and performing rituals to help local people whenever needed. A person close to Lobsang Zoepa told Human Rights Watch that he was “very public-spirited and got along well with people in the community and the village” and “knew quite a lot about the oral history of our monastery and area and community.” Lobsang Zoepa is survived by his wife, Migmar, his son, Tenzin Yeshe, his daughter Tsewang Lhamo, and two other adult daughters.

Political Re-education Imposed on Village and Monastery

Following the death of Lobsang Zoepa, his two adult children were released from detention. But the only other response of the authorities to the suicide appears to have been to continue the daily political education sessions. Few details of the sessions are known except that, as noted above, they focused initially on “Loving the Nation, Loving Religion” and on “opposing separatism,” and included denunciations by cadres of the Dalai Lama.

One month later, however, on October 2, 2019, the county police issued a report on the police social media channel that gives hints as to their content. The police report described a return visit to the monastery by the head of the county Political-Legal Committee and of its Public Security Bureau, Hu Jicheng.[24] During the October visit, according to the report, Hu gave further instructions to the cadres and police stationed in the monasteries. Many of these were similar to those he had given during his previous inspection: the monastery cadres and resident police were to “strictly manage religious affairs in accordance with the law” and to “increase the education and guidance of monks and the masses.” The aim was to ensure that the monks and nuns will “unify their ideas” with the government and will “always listen to the Party and follow the Party.”

These were standard instructions, but the report on Hu’s post-raid visit contains some features that were not present in the report on his visit the year before: it refers, without giving any details, to “recent stability maintenance work,” and notes that Hu told the monastery cadres to “firmly hold the ‘the ring in the bull’s nose,’ [which is] the field of religion.” The latter rhetoric implies that as long as cadres control the religious field, they can maintain the overall stability of the community.

The report also notes that Hu ordered cadres to get monks to “fight against all anti-infiltration and anti-separatism violations and crimes,” a phrase that had not appeared in the previous report. More significantly, the report notes that, on his second visit, Hu was accompanied not just by an interpreter, but also by “a National Security team (guobao dadui) and by [members of] the Administrative Office of the [County Public Security] Bureau (bangongshi shenru xiaqu).” This is an unmistakable indicator that some kind of serious security incident had taken place.

There are no specific references in the October 2019 report to any unrest or problem at the monastery, but details in the photographs show that the situation had deteriorated. The photographs of Hu’s meetings at the monastery the year before had shown Hu, in sunglasses and a leather jacket, smiling for the camera while sitting with groups of monks in maroon robes. One of those photographs had even shown a senior monk, seated next to Hu, looking at his phone as if unconcerned about either the visitor or the camera.

The photographs from October 2019 are quite different: they do not show Hu seated with groups of monks, but show him with only two monks, one in each meeting. In each of the photographs, we see that Hu is attended by police, officials, and interpreters, and that most of them are standing rather than seated. One detail is even more striking: the monks in the photographs are no longer wearing monastic robes. One of those monks shown being interviewed by Hu is Norbu Dondrub, the chaplain or monk in charge of the upkeep of the monastery. He was detained shortly after Hu Jicheng’s visit and, as discussed, was later sentenced to 17 years in prison.

Ten months after the police raid and the death of Lobsang Zoepa, the county police issued a second report. By this time, Hu had been made deputy head of public security for Shigatse municipality—a promotion from county level to prefectural level, and possibly a sign that his handling of the Tengdro case had earned official approval.[25] He was replaced as secretary of the county Political-Legal Committee and as head of Tingri Public Security by a deputy party secretary called Zhang Ling. The report reveals that Zhang, who is described as also director of the county’s State Security Bureau (guo'an ban zhuren), visited Tengdro monastery on July 2, 2020. The report says that Zhang’s aim was “to learn more about the basic situation of the temple, history and culture, and the monks’ family income,” as in a normal “pairing” visit. But no further mention is made in the report of any interest in the monastery’s history, the monks’ living conditions, or in alleviating poverty, and Zhang is not shown bringing rice, food, or other gifts to the monks.

Instead, Zhang’s focus is described as having been on security issues and, in particular, on “carrying out supervision and inspection work in the field related to religion.”[26] His instructions to the monks, as described by the media report, were broadly similar to those of his predecessor, Hu Jicheng. However, there is one important difference. In his instructions to the cadres and police stationed in the monastery, Zhang added one order not mentioned in the previous reports: the officials were to strictly implement “among monks and nuns in the monastery the management system of the need for leave to be requested and for return from leave to be reported (qingxiaojia).” This indicates that monks and nuns were no longer allowed to leave the locality without permission

from officials.

The report also shows other signs of tensions at the monastery. Zhang, it says, carried out “face-to-face, heart-to-heart conversation, and on-the-spot questioning” with the monks, and “gave teachings to all the monks about Chinese law.” Neither of these had been noted in earlier reports of inspection visits. And, unlike Hu’s visit, the photographs in the July 2020 report do not show Zhang seated next to monks, whether as individuals or in a group, as if meeting with them on equal terms. Instead, he is shown, flanked by officials, giving a lecture to the monks, who are seated at school desks with their backs to the camera. Once again, all the monks shown in the photograph of Zhang’s visit are wearing lay clothes.

As usual, very little is revealed by the reports on official social media channels about Tengdro monastery after the 2019 raid, even though these channels are directed at local audiences and their reports do not appear in regional or national media. Nevertheless, details in the reports indicate a significant increase in visits by senior security officials, a hardening of officials’ attitudes to the monks, no signs of gifts of food or other products, a focus on religion as a security issue, restrictions on the movements of the remaining monks, and what appears to be a ban on monks wearing religious robes. Taken together, these details support the conclusion that a significant incident took place at the monastery before Hu Jicheng’s October 2019 visit.

II. The Politics of Sentencing: Online Offenses

Criminal Charges Against the Tengdro Monks

The Chinese government’s criminal case against the Tengdro monks is exceptional in two respects: the available information indicates that the monks were involved in only minor, if any, offenses under Chinese law, and the long sentences they received for such offenses were unprecedented in their severity. These sentences almost certainly violated Chinese law regarding the permitted degree of punishment for criminal offenses.

The various descriptions received by Human Rights Watch suggest that the Tengdro monks were detained for one or more of three activities: for online communications with Tibetans abroad, for possession of photographs or literature relating to the Dalai Lama, and for sending funds abroad.

As explained below, under Chinese law, online communications are illegal only if they threaten social stability or national security in some way, such as by spreading unauthorized information, defrauding citizens, exposing state secrets, or inciting separatism. No evidence has emerged that suggests that the messages exchanged by the Tengdro monks met such standards or infringed any Chinese laws.

The monks were also found, in some cases, to have texts or images relating to the exile Tibetan leader, the Dalai Lama. In Chinese jurisprudence, however, mere possession of materials relating to the Dalai Lama is not in itself a serious offense and may not be technically illegal unless it involves a compounding offense such as distribution of illicit materials or incitement of separatism. In 2005, a Tibetan named Sonam Gyalpo in Lhasa was sentenced to 12 years in prison for possession of photos of the Dalai Lama and related literature,[27] but he had been convicted on previous occasions for offenses of a similar nature and so would have been considered a recidivist.[28]

A more typical case involved 13 or more Tibetan villagers in the neighboring county of Nyalam in 2017. The villagers were Communist Party members and so were not allowed to be religious believers. However, they had hidden “prohibited items involving political problems”—probably photographs of the Dalai Lama—in a cave where they would go secretly to pray, according to an official media report.[29] However, after the police raided the cave, none of the participants were charged with a crime. Instead, three were expelled from the Party while the others were given warnings. This reinforces the view that possession of texts by or relating to the Dalai Lama is not in itself a crime, even when the case involves Party members and officials. In the Tengdro case, as we have seen, at least two detainees—Tenzin Yeshe and Tsewang Lhamo—were released without charges after a few days, even though they apparently had images of the Dalai Lama and other unapproved items on their phones. In strictly legal terms, therefore, the charges against the Tengdro monks cannot be explained by the mere possession of photographs of the Dalai Lama.

Police interrogation of the Tengdro detainees, lastly, reportedly focused on donations to members of the community’s sister monastery in Nepal, founded by Sengdrak Rinpoche, following the 2015 earthquake. Certain foreign transfers of funds are illegal in China and specifically in Tibet. In particular, the Public Security Bureau issued a notice in the TAR in February 2018 that listed the collection of funds or donations as an example of “violations or crimes by underworld forces.” But the notice specified that such transfers were only criminal acts if they involved “compulsory collection” by the organizers, “unjust enrichment,” or donations to the “Dalai clique,” a term used for the exile Tibetan administration in India and associated political activists.[30]

None of these factors appear to have been involved in the Tengdro case. Neither Sengdrak Rinpoche nor his community in Nepal were part of the exile administration, nor were they involved in any known political activities. In religious terms they, like the Tengdro monks, belong to a Tibetan Buddhist school that is distinct from that of the Dalai Lama, and which in the past has not been a focus of police attention in Tibet. Sengdrak Rinpoche had not been to Tibet again after his 1993 visit, but this was because of a general Chinese government policy restricting visits to Tibet by exile Tibetan lamas since around that time and does not indicate that the police had any particular suspicions regarding him. Incoming donations received by the Tengdro monks from their sister community in Nepal do not appear to have been seen as a problem by the police: the available reports indicate that police questioning focused on outgoing donations by the Tengdro monks. For the Tengdro monks to communicate with or send financial aid to their sister-community in Nepal was therefore not illegal under Chinese law, does not seem to have been a previous issue of police concern, and should not normally have led to detention, still less to prosecution.

Chinese law also forbids religious institutions from receiving unauthorized donations from “foreign organizations or individuals,” but only if those donations are not for “activities that are commensurate with the purpose of the religious group or the religious activities site,” if they have conditions attached, or if the amount donated exceeds 100,000 yuan (about US$15,500).[31] Although Tengdro received some support funds for reconstruction of the monastery from its sister community in Nepal, there is no indication that these donations contravened regulations.

Human Rights Watch found no other evidence of possible offenses committed by the monks—for example, as noted above, both their reconstruction of the monastery in 2017 and their erection of a large outdoor statue had received approval from local authorities, as well as their donations to their sister monastery in Nepal, did not involve any use of coercion in collecting the funds.

Chinese authorities have detained and punished Tibetans in the past for actions that are technically legal, such as having images of the Dalai Lama or sending religious donations abroad. However, those cases usually involved accusations of additional illegal acts of a more serious nature and did not on their own lead to heavy sentences. In the Tengdro case, the available evidence suggests that the Tengdro monks had not committed any illegal acts or at most had been involved in only minor infractions of Chinese laws and regulations, for which the sentences, if any, would normally have been minimal.

Other Cases of Extreme Punishment in Tibet

The sentences handed down to Choegyal Wangpo, Lobsang Jinpa, and Norbu Dondrub were extraordinarily severe. Human Rights Watch does not know of any Tibetan, since 2013, sentenced to 20 years or more for a non-violent action not involving any form of protest. Below, we list previous cases in which the courts imposed extreme sentences on Tibetans for non-violent offenses. This survey shows that the sentences given to the Tengdro monks were exceptional, if not unique, and almost certainly violated Chinese law governing sentencing decisions.

Between 1999 and 2013, extreme sentences—20 years and over—were imposed on at least 10 Tibetans for non-violent acts of expression, association, or opinion. Seven of those Tibetans had not been accused of participation in a protest:

- Bangri Choktrul Rinpoche (Jigme Tenzin Nyima), the head of an orphanage in Lhasa, was arrested in August 1999 and given a life sentence (later commuted to 19 years plus 2 years for time previously served, apparently for receiving funds from exile for the orphanage[32];

- Choeying Khedrup, a monk from Tsanden monastery in Sog (Ch.: Suo) county, Nagchu, was sentenced to life in prison on January 29, 2001, for printing and distributing pro-independence leaflets[33];

- Jampel Wangchuk, a senior monk at Drepung monastery in Lhasa, was sentenced to life in prison in 2010, apparently for failing to prevent a protest by monks[34];

- Konchok Nyima, another senior monk from Drepung monastery in Lhasa, was sentenced to 20 years in 2010, apparently for failing to prevent a protest by monks[35];

- Wangdu, a community worker in Lhasa, was sentenced in 2008 to life imprisonment, apparently for distributing information he had received from exiles abroad[36];

- Dorje Tashi, a prominent entrepreneur and hotel owner in Lhasa was sentenced to life imprisonment on June 26, 2010, for having sent donations to the Dalai Lama, although he was only charged with embezzlement, based on evidence that appears to have been largely fabricated[37]; and

- the late Konchok Jinpa,[38] a tour guide from Nagchu, was reportedly given a 21-year sentence in 2013, for distributing information to foreign media and others about Tibetans detained in local protests.

Three other cases of extreme sentencing for non-violent actions involved participation in a protest: Pasang (from Lhasa) and Tsultrim Gyatso (from Labrang in Ganlho Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, in Gansu province) received life sentences for involvement in protests in 2008 that appear to have been non-violent, as did Sonam Lhundrup (from Dranggo in Kardze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, in Sichuan province) following a protest in 2012.

Other Tibetans who received long sentences for involvement in non-violent protests include Thardoe Gyaltsen, a senior monk from Driru (Ch.: Biru) in Nagchu, who received an 18-year sentence in 2014, for peaceful opposition to the crackdown there,[39] and Lodro Gyatso from Sog in Nagchu, who was sentenced to 18 years in prison in 2018, for involvement in a peaceful protest.[40] Lobsang Konchok, a Tibetan from Ngaba in Sichuan province, was given a death sentence in 2013, for alleged encouragement of self-immolation protests in which only the participants were harmed.[41] At least 20 other Tibetans are known to have received sentences of 10 to 15 years for non-violent offenses since 2013.[42]

All of these convictions would appear to violate substantive rights, such as freedom of expression, opinion, and religion or belief, as recognized under international human rights law, or resulted in sentences that were wholly disproportionate to the offense. However, they could be considered crimes under Chinese law, according to which they are usually classified as actions that “endanger state security” or as “incitement to split the country.” The Chinese Criminal Code allows a court to impose sentences of five years or more for such offenses, but only if the defendant is “a ringleader or the one whose crime is grave” (Criminal Code, articles 102 to 106). These punishments are typically invoked only when a defendant is accused of involvement in the organization or establishment of an illegal group, “collusion” with a foreign force, espionage, leading or planning a protest, an act of violence, or recidivism.

From the perspective of Chinese officials, these conditions could be said to have applied in the cases of extreme sentencing listed above, all dating from 2013 or earlier. But in the case of the Tengdro monks, there is no indication of any protest or plan for a protest, any connection with or creation of an illegal organization, any espionage, act of violence, or attempt to spread unauthorized information widely, or previous conviction. And it does not seem that the sentences imposed on the Tengdro monks could have been intended to serve as deterrents, since the trial was secret and the case has never been disclosed to the public. The decision to prosecute the Tengdro monks and the severity of the sentences imposed on them appears instead to have been the result of political calculations by TAR officials. We discuss the evidence for this below (See section: “Behind the Sentences”).

Online Offenses: Regulations up to 2019

An important consideration in the case of the Tengdro monks appears to have been the desire of officials to show their commitment to the ongoing drive in the TAR, as across the country, to increase control over individuals’ use of the internet, including social media.

This section describes recent laws that increasingly proscribe certain forms of online communication and identifies cases in which Tibetans have been accused of breaking these laws, along with the sentences imposed on them, where known. This overview shows increasing attention by authorities to restricting peaceful online expression, but it also shows that the treatment of the Tengdro monks was exceptionally severe compared with other cases in which Tibetans have been convicted of online offenses.

By 2001, China had already introduced more than 60 sets of regulations governing the use of the internet, and numerous other regulations have been issued since then.[43] In June 2017, the Chinese government passed the Cybersecurity Law, leading to a number of nationwide campaigns to “clean up” the online environment, including one initiated in January 2019 to rid the internet and social media of “12 types of negative and harmful information including bad lifestyles and bad pop culture,” such as rumors, pornography, and parody.[44]

More recent regulations have identified specific forms of forbidden political speech, notably the Provisions on the Governance of the Online Information Content Ecosystem (the “Provisions”), passed in December 2019. [45] The Provisions criminalized any information posted on the internet “opposing the basic principles set forth in the Constitution,” “destroying national unity,” “denying the deeds and spirit of heroes and martyrs,” “undermining ethnic unity,” or “undermining the nation's policy on religions.”

In January 2021, the Cyberspace Administration of China announced regulations banning members of the public from writing any online article, blog, or commentary on issues relating to health, politics, economics, education, the military, or certain other topics unless they have received official certification.[46] The authorities shut down 18,489 illegal websites in 2020, referred 7,550 cases for prosecution by the courts, and arranged for website operators to close 158,000 illegal accounts.[47]

In addition to these national developments, local administrations at provincial, prefectural, and sometimes county level have issued their own regulations to reinforce the new restrictions and controls. Regulations issued in Tibetan-populated areas have emphasized issues relating to ethnic relations, separatism, and contact with people or groups abroad.

In October 2017, the Public Security Bureau (PSB) in Machu (Ch: Maqu) county, Kanlho (Ch: Gannan), a Tibetan autonomous prefecture in Gansu province, issued rules “for strictly preventing the spread of ‘illegal’ contents on the internet” including, as its first item, “information containing political contents.”[48] Other administrations in Tibetan-populated areas followed suit: in March 2019, the prefectural government in Kanlho warned that people should “not spread rumors or believe in rumors,” indicating that the former could be considered a crime. The statement added that “if any WeChat group member publishes any illegal information against the laws, he or she will be sentenced to [between] one and eight years in prison.”[49] In August 2019, authorities in Qinghai province, where most of the territory is populated by Tibetans, also warned of prison sentences of up to eight years for posting and sharing “illegal” information that “harms the nation and the Chinese Communist Party.”[50]

The TAR authorities were equally energetic in setting up laws, regulations, and official entities to manage public use of the internet including social media. As TAR Party Secretary Wu Yingjie put it during a November 2016 inspection of the TAR Internet Affairs Office—an agency directly under the Party in Tibet rather than the government—“by carrying through the correct political approach, managing and using the internet properly, [we must] make the Party's voice the loudest voice on the internet.”[51] The TAR authorities accordingly launched a campaign in September 2018 to “rectify illegal crimes in the network communication field,”[52] and issued their own provincial-level regulations in February 2019 to tighten control of online content.

Known as “the ‘Twenty Prohibitions’ on Network Communication Activities” in the TAR, these banned any online content involving “activities to subvert the country, undermine national unity, and overthrow the socialist system” or any use of “network communication tools to fabricate and disseminate information such as provoking ethnic relations, [and] creating ethnic contradictions.”[53] The “Twenty Prohibitions” focused particularly on communications abroad, banning online users who “provide information to domestic and foreign organizations, institutions, or individuals” that “has not been [previously] disclosed by the state” (article 4) or who “collect, produce, download, store, publish, and disseminate information that subverts the country, undermines national unity, and overthrows the socialist system” (article 5). According to one unconfirmed exile report, at the same time the document was issued in February 2019, the TAR authorities were offering rewards of up to 300,000 yuan (about $45,000) for reports by members of the public on illegal online activities.[54]

A mid-level official told Human Rights Watch in 2019 that sub-police stations in every locality already had units by that time that operated under the direction of the TAR Public Security Bureau’s Internet Management Department and managed WeChat and internet communications in their area. Human Rights Watch wrote to WeChat requesting information regarding the TAR PSB’s Internet Management Bureau and its use of its platform (See Appendix). At the time of writing, Human Rights Watch had not received a response from WeChat.

These national, provincial, and local laws and regulations restricting online communications were issued in the wake of a series of security-related laws that were passed in China from 2014 onwards. These included laws on counter-espionage (2014), national security (2015), and national intelligence (2017), all of which broadened the definitions of espionage and other illegal activities. These laws increased the focus on security issues, in particular in relation to ethnic minorities. The Detailed Implementation Rules for the Counter-espionage Law (2017), for example, widened the definition of espionage to include any acts “carrying out division of the country,” “undermining national unity,” or “inciting ethnic divides” (article 8). It specifically banned the transmission of any texts or audiovisual materials with such purposes, adding to the already intensive surveillance of communications by Tibetans, Uyghurs, and other minorities in China.

Arbitrary Detention for Online Offenses

From 2008 through 2020, the authorities have detained at least 97 Tibetans for online activities or communications that were deemed illegal, according to a database of political prisoners maintained by the US-based Congressional Executive Commission on China. The Executive Commission draws its data primarily from foreign and exile media reports. A further 20 cases have been reported since January 2021.

In most cases, the punishment given to detainees in these cases is not known, or, in some instances, involved only a few days or weeks in detention. For example, in October 2013, a Tibetan woman named Kalsang from Driru in Nagchu was detained for allegedly expressing “anti-China” sentiments on her WeChat account and for having stored “banned pictures of the exile Tibetan leader the Dalai Lama” in her cell phone.[55] The following year, Lobsang Choejor, a monk of Drongsar Monastery in Chamdo (Ch.: Changdu), was detained for an unknown period for sending out information to “outside contacts” through WeChat and distributing teachings and talks by the Dalai Lama, but is not known to have been sentenced.[56]

In 2019 more such cases were reported:

- Wangchuk, a Tibetan man from Nyalam county (next to Tingri county), was detained, probably for sharing some books by or about the Dalai Lama on WeChat;[57]

- Rinso, a Tibetan from Dzorge (Ch.: Ruo’ergai) in Sichuan province, was detained for 10 days for sharing a photo of the Dalai Lama on WeChat;[58]

- A Tibetan monk named Sonam Palden, 22, from Kirti Monastery in Ngaba (Ch.: Aba) county, was held in connection with his WeChat posts about the Tibetan language and Chinese policy;[59]

- Three Tibetans in Kanlho prefecture of Gansu province were detained for communicating on social media with friends and family outside Tibet;[60]and

- Two Tibetans in Tingri county were detained for the same offense. One was held at the county detention center for over a month and the other was held there for 20 days. Police reportedly subjected them to beatings and interrogation.[61]

Human Rights Watch wrote to WeChat requesting information on its data sharing practices with the TAR Public Security Bureau authorities and on its position regarding Chinese authorities’ surveillance of its platform (See Appendix). At the time of writing, Human Rights Watch had not received a response from WeChat.

These instances appear to have involved brief, deterrent punishment for online offenses.

Similar cases were reported in March 2020, when the Chinese authorities arrested 10 people in Lhasa for spreading “rumors” about a coronavirus outbreak on March 1, and shut down 75 WeChat groups in the TAR.[62] In the first weeks of 2020, police in Qinghai province investigated 72 people for spreading rumors online, according to the New York Times.[63] Those cases are not known to have resulted in trials or prison sentences.

Long Sentences for Online Offenses

In 19 of the 117 known cases involving Tibetans accused of online offenses, detainees were tried and given sentences averaging 4.5 years each, according to our analysis of existing reports. These cases appear to have been treated with exceptional severity because officials alleged that the online messages in these cases were connected to activities—such as organizing a protest, forming a non-approved organization, sending security-related intelligence to foreign or exile organizations, and spreading non-approved information widely within the domestic community—that officials deemed threats to social stability or national security.

Such cases included those of Atruk (Adrag) Lopoe,[64] Jamyang Kunkhyen,[65] and Lothok, who were sentenced in 2007 to 10, nine, and three years, respectively, for sending photographs abroad showing a protest in Lithang (Ch.: Litang), a Tibetan area within Sichuan province.[66]

Online messages relating to self-immolation protests led to particularly severe sentences after a ruling was issued by China’s Supreme Court and its top prosecution body, in December 2012, classifying any encouragement of self-immolation as liable to the charge of “intentional homicide.”[67] These led to a series of long sentences:

- In 2013, Lobsang (Lorang) Konchok was given a suspended death sentence for intentional homicide after posting news of self-immolations as well as allegedly inciting the suicide protests;

- In the same case, his nephew, Lobsang Tsering, was sentenced to 10 years, also for inciting suicide protests;[68]

- In March 2013, a court in Tsoshar (Ch.: Haidong) prefecture, Qinghai province, gave three Tibetans—Gyurmey (or Jigme) Thabke, Kalsang Dondrub, and Lobsang—sentences of up to six years for “using others’ self-immolation incidents to disseminate text and images relating to Tibetan independence;”[69]

- In July 2013, a monk from Zilkar Monastery in Tridu (Ch.: Chenduo) county, Qinghai province, Tsultrim Kalsang, received a 10-year sentence for providing information to foreign media about a double self-immolation;[70]

- Also in 2013, a court in Malho (Ch.: Huangnan) prefecture, Qinghai province sentenced two Tibetans, Choepa Gyal and Namkha Jam, to six years each for sending information and images about protests or dissent abroad; and

- In the same case, a Tibetan named Chagthar, was sentenced to four years for editing and distributing images and text about self-immolations.[71]

In some cases, possession of information about a self-immolation alone (without evidence the person had shared it with anyone else) was enough for a prison sentence, as in the case of a 20-year-old thangka painter, Ngawang Tobden, who received a two-year sentence in Lhasa in February 2013 for photographs of self-immolations and of the Tibetan flag found on his phone.[72]

Lengthy prison sentences have also been reported in the cases of Tibetans convicted of sending messages relating to environmental issues. In 2014, Jamyang Wangtso and Namgyal Wangchuk from Riwoche (Ch.: Leiwuqi) county, Chamdo municipality, TAR, received seven- and five-year sentences, respectively, after they shared an image on WeChat of two Tibetans wearing robes trimmed with animal fur as part of an effort to combat the wearing of fur.[73] In December 2019, a group of nine Tibetans from Gabde (Ch.: Gande) in Golok (Ch.: Guoluo) prefecture, Qinghai province, including environmental campaigner Anya Sengdra, received sentences of up to seven years in prison after they created two WeChat groups about local corruption and environmental protection,[74] which led them to hold peaceful protests against local officials.[75]

Enforcement of Online Restrictions since Mid-2020

Since mid-2020, exile media have reported that controls over online communications have become stricter throughout Tibet.[76] These claims were substantiated in July 2020, when two Tibetan musicians, Khandro Tseten and Tsogo, from Tsekhog (Ch.: Zeku) in Qinghai province, were sentenced to up to seven years for sharing a song on social media that praised the Dalai Lama.[77]

The intensification of restrictions on online activities was made clear in November 2020, when the TAR authorities published a document called “Notice of the Tibet Autonomous Region on not using information networks to implement activities to split the country and undermine national unity.”[78] The notice announced additional details of restrictions on online content, focusing entirely on expressions of political opinion or organization. This confirmed that the main focus of online control in the TAR is political speech, especially discussions of Tibet’s historic status and any criticism of China’s policies in Tibet, rather than an attempt to crack down on rumors, pornography, or extortion, which are often the focus of online “cleansing” drives in other parts of China.

The 2020 TAR notice banned any online activities that relate to undermining “nationality unity” and specifically outlawed any online information that “distorts history, downplays national consciousness, uses religious content, religious activities, etc. to attack the party and state policies, or slander the socialist system.” It also prohibited any postings that “distort facts, spread rumors or spread false information to provoke ethnic relations and undermine ethnic unity.” The notice also criminalized any technical assistance enabling people to view foreign websites that “undermine national unity.”[79]

Initial reports indicate that enforcement of the new regulations has been stepped up since late 2020, both within the TAR and in adjoining Tibetan areas. In some cases, those accused of violations have received short prison sentences, fines, or periods of detention:

- In August 2020, the Tsholho (Ch.: Hainan) People's Intermediate Court in Qinghai sentenced Tibetan student Jampa Tsering to 1.5 years in prison for “inciting splittism” after he posted an image of an “illegal football team flag and logo”— possibly a reference to the forbidden Tibetan national flag – in a message relating to a football competition in Serchen county;[80]

- On October 13, 2020, a court in Golog (Ch.: Guoluo) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Qinghai province sentenced Tashi Gyal (Ch.: Zhaxijia), a 50-year-old Tibetan herder from Ragya in Machen county, Golog, to one year in prison for “inciting separatism.” Tashi Gyal had downloaded four images and a video of the Dalai Lama from the internet in 2014, and had forwarded these items to a group of friends on his WeChat (Ch.: Weixin) channel on three occasions that year. On three days in 2015, he had sent these friends a photograph of the forbidden Tibetan flag and three videos with messages from exile leaders. At the time of the hearing, he had already been in custody for five months;[81]

- In December 2020, a Tibetan named Lhundrup Dorje from Machen (Ch.: Maqin) in Golok prefecture, Qinghai province, received a one-year prison sentence on the charge of “inciting separatism” after posting pictures and religious teachings of the Dalai Lama on his Weibo and WeChat accounts that included a graphic with the slogan “Tibetan independence;”[82]