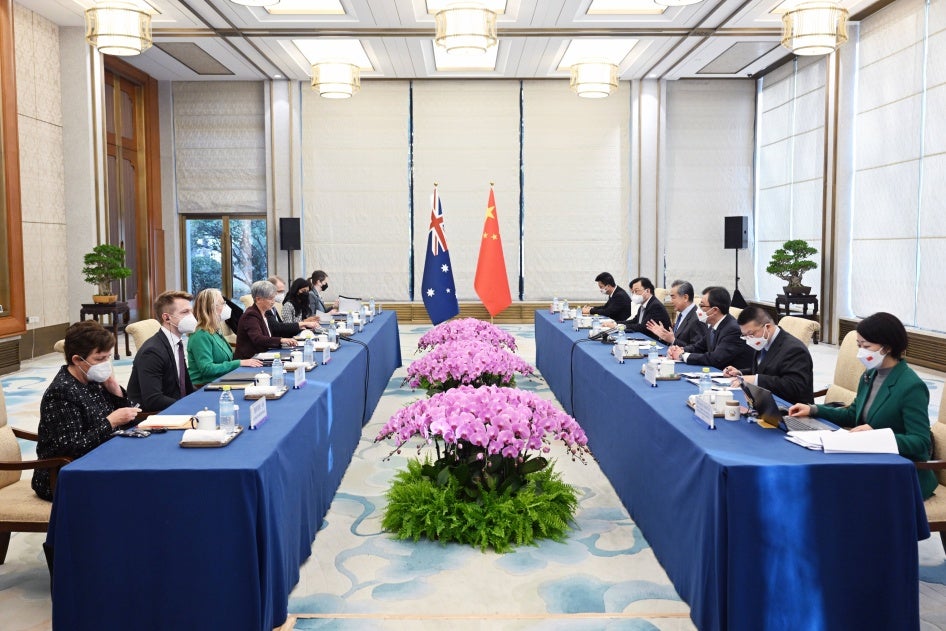

On Wednesday, China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi will travel to Australia to take part in the Australia-China Foreign and Strategic Dialogue, a longstanding format where they will discuss trade, security, and other bilateral and international issues. During the visit, the Australian government should move beyond statements of concern and make clear their intention to seek accountability for China’s ongoing human rights violations.

This is the first visit of a Chinese foreign minister to Australia since 2017. While the Australian government’s focus continues to be “stabilizing relations” between the two countries, discussions should include systematic efforts to tackle persistent human rights violations by the Chinese government.

When a Chinese court imposed a suspended death sentence on the writer and Australian citizen Dr. Yang Hengjun earlier this year, Australia’s Foreign Minister

Penny Wong was “appalled,” saying the Australian government would be “communicating our response in the strongest terms.”

And when the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights released a report on Xinjiang in 2022, outlining a systematic campaign by the Chinese government to repress Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims that “may constitute … crimes against humanity,” the Australian government said they were “deeply concerned” about the findings.

Even earlier this month, the government once again expressed its “concern” about China’s human rights violations, this time regarding Hong Kong’s draconian new domestic security bill known as “Article 23,” which will further erode people’s long-cherished rights and freedoms.

Publicly expressing concerns is an important element of a human rights foreign policy. But given the trajectory of human rights abuses in China, it is clearly not enough. To hold China accountable, expressions of concern should be bolstered by concrete action. While Wang Yi is in the country, Penny Wong should outline specific steps Australia will take if the Chinese government doesn’t reverse its oppressive policies and practices.

Such steps might include imposing sanctions on senior Hong Kong officials, initiating an investigation into grave crimes committed in Xinjiang, spearheading a project to assist Uyghurs living abroad to locate missing relatives in Xinjiang, and informing Wang that Australian authorities will investigate and appropriately punish acts of repression by Chinese officials and their proxies in Australia that violate Australian law.

Principled words have their place. But the Australian government needs to recognize when actions speak louder than words.