The following submission was presented to the UK parliament’s All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Sudan and South Sudan in February 2023, based on research by Human Rights Watch conducted since 2021. The submission was made prior to the outbreak of fighting between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), the military, and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a competing military force, in April 2023. The fighting has spread throughout Sudan, and notably once again to West Darfur. While Human Rights Watch has made some minor changes, the submission does not reflect events since April 2023.

- Human Rights Watch welcomes the APPG on Sudan and South Sudan’s inquiry into ‘A New Wave of Violence in Darfur.’ This inquiry is timely, not only for addressing the plight of the Darfur population, but also the underwhelming international response to the ongoing violence and abuses. Human Rights Watch is an independent non-governmental organisation that monitors and reports on compliance with international human rights law in some 100 countries around the world.

- This submission summarises the research findings conducted by Human Rights Watch between 2021 and early 2023 into the large-scale attacks by armed men from Arab groups and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in West Darfur. Human Rights Watch investigated the abuses committed during three of the largest attacks that occurred in that period: one in El Geneina, the capital of West Darfur, which saw four days of attacks on heavily populated areas of the town in early April 2021, and two bouts of attacks in Kereneik town and surrounding areas in December 2021 and again in April 2022. The attacks and abuses we documented in these three incidents matched broader patterns of abuses against non-Arab communities in West Darfur since 2019.

- The Rapid Support Forces (Quwat al-Da’m al-Sari’ in Arabic, or RSF) are a Sudanese military force currently in conflict with the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF). The RSF are historically drawn largely from Arab groups, notably from the Riziegat community, and was created in mid-2013 to suppress rebel armed groups throughout Sudan. Human Rights Watch’s research documented abuses by the RSF in Darfur between 2013 and 2014 as well as in the context of the crackdown on protests in Sudan’s capital, Khartoum, against the government of former President Omar al-Bashir in 2019.[1]

- Since late 2019, West Darfur in particular has experienced devastating large-scale attacks by militias mobilised in Arab communities, joined by members of the RSF, against internally displaced African communities, primarily from Massalit and Bargo, who bear the brunt of repeated attacks on local communities, their homes, hospitals, schools, and shops.

- Human Rights Watch found that this wave of violence in West Darfur is rooted both in existing, unaddressed historical grievances, and a context of impunity for grave violations, but some of the dynamics of the violence are new.

- While various factors, often localised ones, played a role in the uptick in violence, key contributing factors have been the United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur (UNAMID) pullout in 2020 which removed a clear deterrent force, the failure of the country’s short-lived transition and the peace agreement to address outstanding grievances of the conflict, including concerns of the displaced communities as well as those of Arab pastoralist communities, and the failure of the authorities since then to provide meaningful civilian protection and justice for past and ongoing abuses.

- Following the formation of the transitional government in 2019, Sudanese leaders vowed to protect civilians in Darfur and developed a plan for protecting civilians that primarily provides for the deployment of joint forces from government forces and Juba Peace Agreement signatory groups and strengthening access to justice.[2] However, the multiple episodes of violence in the region have laid bare the failure of Sudanese leaders and authorities to protect those at risk or deter attackers, resulting in significant harm to local communities and dire humanitarian consequences.

- Attackers committed a wide range of abuses, killing and injuring hundreds of local residents while they were fleeing or seeking refuge, burning and looting houses and other properties, targeting health care facilities and internally displaced people’s (IDP) camps. Most of those killed in these attacks were adult men, but children, women and elders were not spared. These attacks have left a massive trail of destruction and displacement.

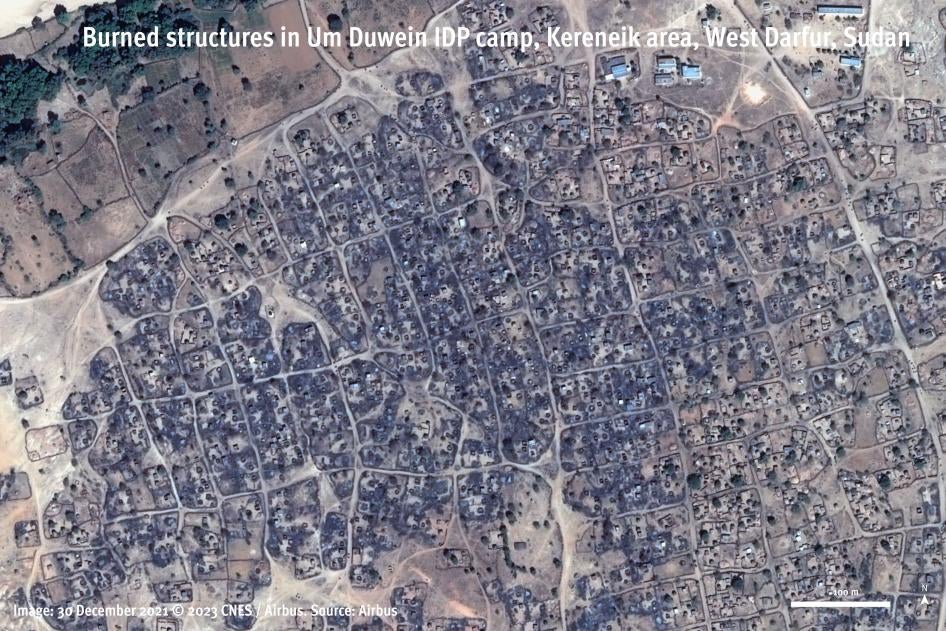

- During this research, Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed around 50 survivors from West Darfur and conducted 24 interviews with community leaders from Arab and non-Arab groups, lawyers, doctors, humanitarians, diplomats, UN officials, and international experts. Researchers reviewed satellite imagery before and after the three attacks to help determine the significant levels of destruction within residential areas notably in displaced people’s camps.

- Evidence collected by Human Rights Watch show how these attacks, despite being triggered by what appears to be individual incidents between members of Arab and non-Arab groups, resulted in the rapid mobilisation of armed groups of Arabs, including members of the RSF. In each incident, attackers came on horses, camels, motorbikes, and land cruisers(so-called technicals), including RSF vehicles, and used different kind of weapons from assault rifles to Rocket Propelled Guns (RPGs) and heavy anti-aircraft guns.

- Based on the evidence of survivors and analysis of video footage posted to social media, it can be concluded that members of the RSF participated in these attacks, as identified by their uniform and insignia. While Human Rights Watch did not find evidence of centrally ordered commands from the RSF leadership prior to the attacks, RSF leaders do not appear to have given orders preventing participation before or during these attacks and subsequently took no reported measures against RSF members who perpetrated abuses against local communities during these attacks.

- Human Rights Watch also found that some youth from the Massalit community, driven by a sense of insecurity in the face of repeated attacks, have been organising themselves in “self-defense” militias. Evidence suggests the Massalit “self-defense” groups engaged in some clashes with armed Arab groups during the attacks on both El Geneina and Kereneik. Sources Human Rights Watch interviewed suggest the establishment of these militias and increased weapon proliferation among the Massalit community took place following another large-scale attack, in 2019, on the Krinding IDP camp in El Geneina.

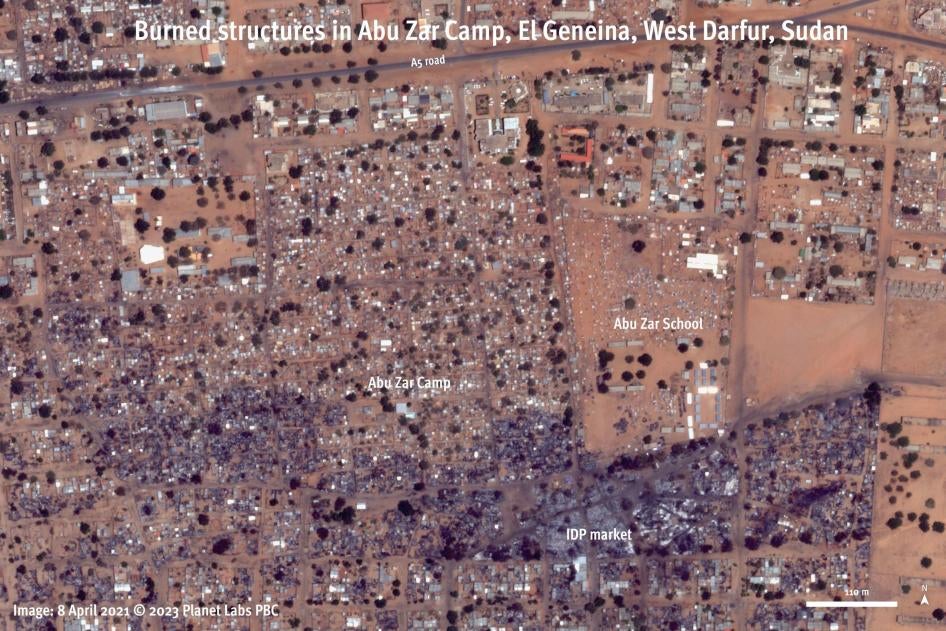

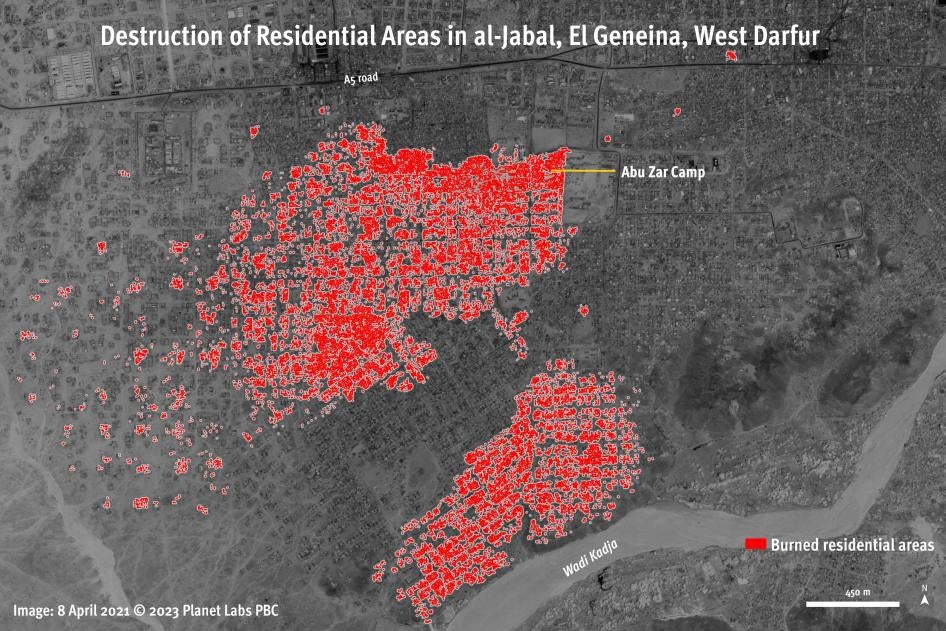

Violence in El Geneina, April 2021 - El Geneina, the capital of West Darfur, is a home for non-Arab groups such as the Massalit and Bargo, as well as Arab nomadic groups. Between April 4 and April 7, 2021, well-armed Arab militias, supported by members of the RSF, attacked heavily populated, primarily Masalit, neighborhoods, notably al-Jabal Avenue area, shooting indiscriminately, looting, and setting fire to private property, notably homes.

- Doctors and community leaders said the violence left at least 120 people dead and hundreds injured. A doctor who examined many of those killed and injured during the attacks said that many of the gunshot wounds were in the head or neck.

- Many of the affected neighborhoods were near government buildings, which were guarded by members of the SAF and the Central Reserve Police (CRP), a militarised police unit. Witnesses said government forces stood idle in the proximity of the attacks and did not intervene to protect local residents.

- Witnesses also described brief clashes on April 4 between groups of armed Arab and Massalit fighters in al-Jabel Avenue area, which is El Geneina’s most populated neighborhood and is divided into blocks based on ethnic lines between Arab and African groups, and on April 6 inside Abu Zar displaced people’s camp, before armed Arab militia conducted a massive attack on the camp, resulting in killings, looting, and destruction of property.

- Residents said that medical staff and facilities were also attacked, by armed Arab groups and the RSF, on several occasions over the three days of violence.

- Human Rights Watch analysed satellite imagery captured from the morning of April 5 until the morning of April 8, in which smoke plumes, active fires and burn scars are progressively visible over distinct areas and multiple locations. Human Rights Watch also reviewed thermal anomaly data collected by an environmental satellite sensor that detected the presence of multiple active fires on the southwestern part of El Geneina between April 5 and 7. The fires, detected during the day and night, confirm the continuity of these attacks. Attacks in Kereneik, December 2021 and April 2022

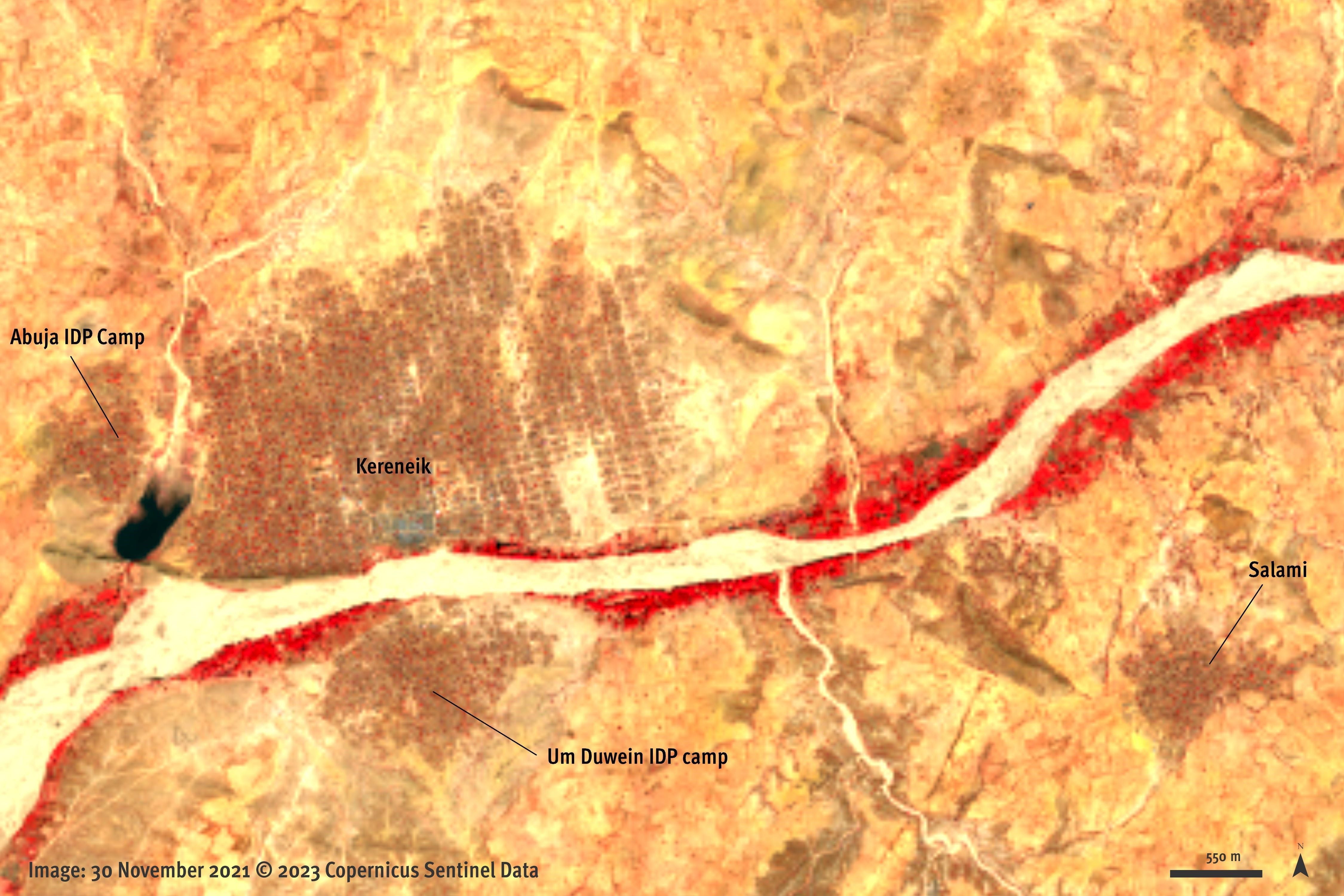

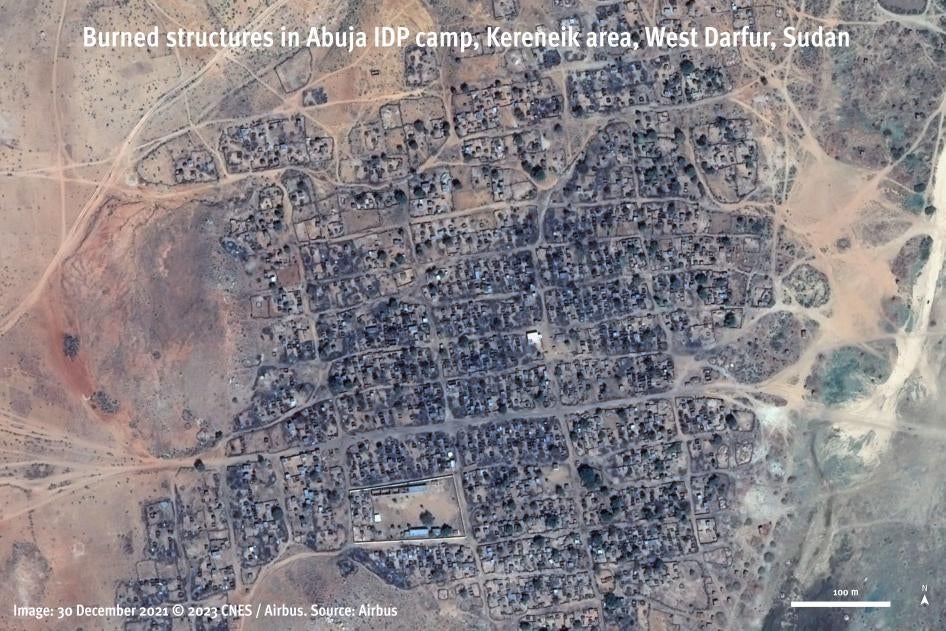

- Kereneik town, 80 kilometers west of El Geneina, experienced two large-scale attacks in the space of four months in late 2021 and early 2022. The first, between December 4 and 6, 2021, was triggered by a personal dispute between members of Arab and non-Arab groups in Kereneik town on December 4. The government sent in re-enforcement forces. On December 5 armed men from Arab groups, joined by RSF, attacked community members in the town.

- The International Organisation for Migration (IOM) reported that at least 65 people were killed and over 70 injured as a result of the attack on December 5 and at least 15,500 people were displaced.[3]

- Witnesses said that government reinforcement forces sent in before the attack did not deter attackers from wreaking havoc across the town, killing, injuring, and destroying properties. The attackers also targeted the two main IDP camps in town: Um Duwein and Abuja. Witnesses described how RSF attackers fired on their straw-made houses with heavy machine guns, setting fire to the houses and resulting in a massive level of destruction in the camps and other residential areas in the town.

- Arab militias and RSF attacked the town once again on April 22, 2022. During the attack, fighting with local Massalit forces and members from Sudanese Alliance Forces, a Juba Peace Agreement signatory group based in West Darfur, ensued. The attack left at least eight people dead. Two days later, a much larger attack against residents and community property took place. Hundreds of mobilized armed Arabs and RSF members targeted the town and surrounding villages. Doctors and community leaders shared with Human Rights Watch a list of 161 persons killed during this fighting, including 21 children and 20 women, many of whom were killed while fleeing for safety or while hiding. Human Rights Watch corroborated, from several sources, the killing of nine men and one woman who were named on the list.

- Witnesses described to Human Rights Watch how attackers, mobilised from different parts of Western Darfur, killed people, and looted and burned houses on April 24. The armed Arab groups also targeted surrounding villages during these attacks. According to the UN, 36 villages across the locality were damaged. Five of them were fully burnt and looted.[4] Human Rights Watch investigated the impact of the attacks in two of the affected villages, Shutak and Salami.

- In Salami, community leaders from the village said attackers arrived early in the morning, almost simultaneously as the attackers in Kereneik town. They shot at people fleeing and entered homes, and looted, and burned property. As a result, 18 men were killed and 680 out of 710 houses were completely burnt and destroyed. Satellite imagery recorded on April 24 of a village southeast of Kereneik, analyzed by Human Rights Watch and confirmed by local sources as Salami, shows massive fires in the village. Imagery recorded on April 29 shows the village reduced to ashes. Impact of the Attacks on Civilians

- In El Geneina town alone, IOM estimated in August 2022 that 83,049 individuals were still displaced by the multiple bouts of fighting.[5] The UN at the time said that around 28,000 people were still displaced following the two attacks in Kereneik with many living in gathering points in the town and others in El Geneina.[6] Survivors who spoke to Human Rights Watch at the time reported difficult living conditions in these gathering sites, including inadequate access to food, shelter, and clean water, with no steps from authorities to rebuild destroyed homes and camps.

- Attackers also burned commercial shops and killed cattle owned by displaced communities, both of which were crucial sources of income and livelihood for many families in these areas.

- The April 2022 attack in Kereneik, not only resulted in yet another cycle of displacement for many of those affected, but also happened at the start of the farming season, impacting the ability of many to farm and cultivate their crops. According to UN World Food Program (WFP) as of June 2022, Kereneik was the town with the highest rates of food insecurity across the region.[7]

Government Response: Participation of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in Attacks and Failure of Authorities to Protect Civilians - The wave of violence in West Darfur exposed the severe inadequacy of the authorities’ efforts to protect civilians. Government forces present in El Geneina and Kereneik during the attacks retreated from their positions inside residential areas or stood idly near government buildings, leaving local residents at extreme risk. In all three attacks documented by Human Rights Watch, members of RSF forces facilitated and joined the attacks on the local community and their homes.

- For instance, survivors from the attacks on two displaced persons camps in Kereneik in December 2021 said RSF forces deployed around the camps on the eve of the attack, ostensibly to provide protection, and later joined the armed Arabs in their targeting of the camps.

- Local residents of Kereneik town said they warned military commanders and local officials of the mobilisation of Arab groups a day before the April 24 attack, but that officials had downplayed their concerns. Survivors also said soldiers from the SAF, stationed at the local garrison in the town, stood idly by as attackers gunned down people fleeing toward the garrison to find refuge.

- The weak government response, combined with the participation in the attacks by members from the RSF, a force that had continued to be regularly deployed across Darfur for the purpose of enforcing security and peace prior to the outbreak of fighting in April 2023, underscored the very real fears expressed by affected communities that deployment of more forces will not deliver stability. Human Rights Watch repeatedly raised concerns with diplomats and humanitarians that in the absence of security sector reform, deployment of abusive forces will likely result in further abuses, not less.

Accountability and Prevalence of Impunity - Authorities in Khartoum had formed investigative committees in the aftermath of the three attacks documented for this submission, but none led to any meaningful prosecutions or trials. Reprisals against complaints and witnesses from a previous attack on a displacement camp in El Geneina in 2019 appeared to have chilled the appetite of communities affected by the violence for seeking redress, adding to challenges in access to justice given the weak presence and capacities of prosecutorial and judicial authorities in West Darfur.

The International Response - The international response to the killings of hundreds and displacement and destruction was muted. Sudanese authorities clearly failed to uphold their commitments to protect civilians in Darfur. Repeated statements from international actors, notably the UN, continued to remind authorities of their duty to protect civilians and investigate abuses.[8] However, these same international actors failed to take concrete measures to ensure that the authorities follow through on these commitments.

- During the upended transition and following the 2021 coup, Darfur continued to fall off the radar of many international actors. One consequence of this was that the United Nations Integrated Assistance Mission in Sudan (UNITAMS) and other international mechanisms had reduced capacity to monitor and report on the abuses across Darfur.

[1] Human Rights Watch, Men with No Mercy: Rapid Support Forces Attacks against Civilians in Darfur, (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2015), https://www.hrw.org/report/2015/09/09/men-no-mercy/rapid-support-forces-attacks-against-civilians-darfur-sudan; and Human Rights Watch, They Were Shouting ‘Kill Them’: Sudan’s Violent Crackdown on Protesters in Khartoum, (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2019), https://www.hrw.org/report/2019/11/18/they-were-shouting-kill-them/sudans-violent-crackdown-protesters-khartoum

[2] United Nations Security Council, “Letter dated 21 May 2020 from the Permanent Representative of the Sudan to the United Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council,” May 21,2020,S/2020/429, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3864630?ln=en.

[3] IOM, “Sudan - Emergency Event Tracking Report - Kereneik (Kereneik Town), West Darfur (Update 005),” January 12, 2002, https://dtm.iom.int/reports/sudan-emergency-event-tracking-report-kereneik-kereneik-town-west-darfur-update-005?close=true.

[4] UN OCHA, “Sudan Kereneik Conflict, West Darfur Situation Report No. 01 (As of 1 June 2022),” June 9, 2022, https://reliefweb.int/report/sudan/sudan-kereneik-conflict-west-darfur-situation-report-no-01-1-june-2022.

[5] IOM, “Sudan - Emergency Event Tracking - Ag Geneina, West Darfur (Update 029),” August 7, 2022, https://dtm.iom.int/reports/sudan-emergency-event-tracking-ag-geneina-west-darfur-update-029.

[6] IOM, “Sudan - Emergency Event Tracking Report - Kereneik (Kereneik Town), West Darfur (Update 010),” September 26, 2022, https://dtm.iom.int/reports/sudan-emergency-event-tracking-report-kereneik-kereneik-town-west-darfur-update-010.

[7] WFP, “Sudan: Comprehensive Food Security and Vulnerability Assessment (CFSVA) - Summary Report, Q1 2022 - June 2022,” June 16, 2022, https://reliefweb.int/report/sudan/sudan-comprehensive-food-security-and-vulnerability-assessment-cfsva-summary-report-q1-2022-june-2022.

[8] For instance see, UN OHCHR, “Press briefing notes on violence in West Darfur,” April 9, 2021, https://www.ohchr.org/en/2021/04/press-briefing-notes-violence-west-darfur; UNITAMS, “Special Representative of the Secretary-General Deplores Heinous Killings of Civilians in West Darfur, Calls for End of Violence and Transparent Investigation,” April 24, 2022, https://unitams.unmissions.org/en/special-representative-secretary-general-deplores-heinous-killings-civilians-west-darfur-calls-end; “Secretary-General Deplores Killings of Civilians in West Darfur,” United Nations Press Release, SG/SM/21249, April 25, 2022, https://press.un.org/en/2022/sgsm21249.doc.htm.