Migration may be an increasingly contentious issue in South Africa, but that does not justify taking an axe to refugee rights and chipping away at the country’s commitments under the United Nations’ 1951 Refugee Convention, as the Department of Home Affairs (DHA) recently proposed alongside other immigration reforms.

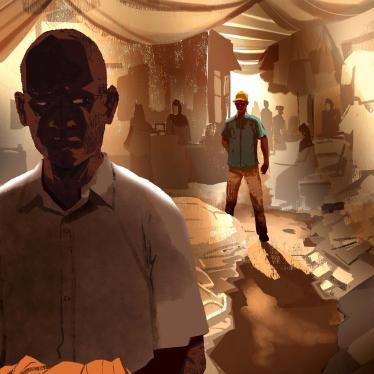

Frustrations have risen across the board. Scapegoating of foreigners by officials has pushed many South Africans to blame migrants for their economic woes. Migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers suffer from xenophobic attacks and a backlogged asylum system. Home Affairs minister Dr. Aaron Motsoaledi characterized current migration legislation as “unworkable,” citing some contradictions between existing laws.

Among the DHA’s proposals are that South Africa withdraw from the Refugee Convention and reaccede to it with reservations, cherry-picking which rights to respect. However, the need for immigration reforms does not give the government carte blanche to toss away its human rights commitments.

At a November 12 press conference, Motsoaledi claimed South Africa “does not have the resources to grant the socio-economic rights envisaged in the 1951 Convention.” Refugee rights to education and work are likely ones the DHA would put on the chopping block.

This would be a damaging backslide on South Africa’s commitments. In 2018, South Africa endorsed the Global Compact on Refugees, which builds on the Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework. These instruments recognize the importance of refugee integration and inclusion, highlighting that access to education and labor markets promotes refugee self-reliance and contributes to local economies.

DHA is also proposing a “safe first country” rule that could deny asylum to people who transited through other countries en route to South Africa. However, without measures to guarantee impacted asylum seekers would be safe in those countries or have access to effective protection, such a rule would risk sending people to chain deportations and other harms, in violation of international law. For example, Greek authorities have sent back asylum seekers that transited Turkey, claiming it was “safe,” yet refugees and asylum seekers there suffered grave abuses and even deportation to Afghanistan, Syria, and other refugee-producing countries.

South Africa’s constitution proudly proclaims that it was founded on the values of human dignity and that “South Africa belongs to all who live in it, united in our diversity.” Officials should keep these values in mind ahead of the country’s 2024 elections and ensure immigration reforms protect, not undermine, refugee rights.