Introduction

Corruption is a structural problem that undermines human rights throughout Honduras. The ongoing negotiations between President Xiomara Castro’s administration and the United Nations Secretary-General to create a UN-backed commission to fight corruption and impunity provide a unique opportunity to learn from past experience and make lasting progress.

This briefing paper focuses on cases that illustrate corruption’s impact on human rights and the importance of an international commission that addresses structural problems hindering the fight against corruption in Honduras. This briefing paper includes recommendations aimed at the creation of an effective and independent international commission and the building of a strong, resilient Honduran anti-corruption and justice system capable of fighting corruption in the long term.

Methodology

This briefing paper is based on research conducted by Human Rights Watch during 2022 and 2023, including trips to Tegucigalpa, Honduras, in January 2022 and June 2023. We reviewed 14 corruption case files, interviewed the chief prosecutor in the cases, and met with victims who were the plaintiffs in one case. We also met with doctors at a mobile hospital whose purchase is the focus of a corruption case. We interviewed dozens of officials, prosecutors, diplomats, anti-corruption and international anti-corruption commissions’ functioning experts, and representatives of civil society and UN agencies in person or remotely.

Selected Cases of Corruption Impacting Human Rights

The UN Convention Against Corruption, which Honduras ratified in 2005, obligates the state to ensure the existence of independent and effective authorities charged with investigating and combating corruption.[1]

Likewise, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which Honduras ratified in 1981, acknowledges that countries have varying levels of resources and calls upon governments to implement rights progressively, commensurate with the resources available.[2]

However, gross misallocation of resources to the detriment of the enjoyment of economic and social rights can constitute a human rights violation. The unjustified diversion of funds from health services and facilities, as in the case of the mobile hospitals in Honduras described below, is an example of such abuse.[3]

Diversion of public resources through corruption and mismanagement will generally violate a government’s obligation to “progressively realize” economic, social, and cultural rights because it reduces the available resources a government has to invest in essential services. Human Rights Watch research has documented the impact corruption can have on the realization of economic, social, and cultural rights in various countries.[4]

In nearly all corruption cases that Human Rights Watch reviewed, corruption had strong links to human rights violations. We had access to the files of cases uncovered by the Unidad Fiscal Especial Contra la Impunidad de la Corrupción (UFECIC), a Honduran prosecutorial unit working with the Mission to Support the Fight against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras (MACCIH), the Organization of American States-backed commission that fought corruption from 2016 to 2020. The prosecutorial unit that replaced the UFECIC, once MACCIH left, called the Unidad Fiscal Especializada Contra Redes de Corrupción (UFERCO), continued and carried out new investigations with limited support from the Attorney General’s Office.

Examples of corruption’s impact on human rights can be found below:

Mobile HospitalsDuring a research trip to Tegucigalpa in 2022, Human Rights Watch visited a mobile hospital, operated by the Hospital Escuela, the acquisition of which was marred by corruption during the Covid-19 pandemic. Between March and April 2020, a government-owned company spent nearly US$50 million to purchase seven mobile hospitals for Covid-19 patients; a court convicted the company’s director and manager of corruption in connection with the purchase in 2022. There is no question that Honduras needed additional hospital capacity. It suffered from limited capacity of intensive care unit (ICU) beds throughout the pandemic, and had only 62 ICU beds in December 2020, according to Ministry of Health data.[5] The seven mobile hospitals would have added 260 ICU beds. But anticorruption organizations in Honduras found evidence of overpricing and irregularities in the purchasing process.[6] In June 2020, the Asociación para una Sociedad más Justa (ASJ), a non-governmental organization, requested quotes from the same supplier for the same products and the supplier offered them for $34.5 million, about 30 percent less than what the government had paid.[7] ASJ also audited the purchasing process and found that it was carried out without consulting with medical experts or coordinating with public health officials, and that the purchase was made through an intermediary selected in a highly discretionary manner. The mobile hospitals arrived months later than agreed and proved inadequate for Covid-19 patients. When Human Rights Watch visited the mobile hospital in Tegucigalpa in 2022, beds were crowded together, and the units had no ventilation. The president of the Honduran medical association told Human Rights Watch that those hospitals posed a high risk of Covid-19 exposure to both patients and health workers.[8] From the beginning of the pandemic through 2022, Honduras experienced periods during which its hospitals were overwhelmed and unable to assist patients. The purchase of the overpriced, inadequate mobile hospitals exacerbated the problems. The president of the Honduran medical association told Human Rights Watch that in some ways, the effects of corruption had “been worse than the pandemic itself,” by compounding its harms.[9] Research has shown that crises can exacerbate corruption, while diminishing attention to it.[10] Officials are more likely to demand bribes, and, with oversight mechanisms distracted, overwhelmed, or sidelined, emergency spending can be ripe for abuse.[11] In June 2022, an anticorruption court convicted the director of the government-owned company that purchased the mobile hospitals of fraud against a public entity and sentenced him to almost 11 years in prison.[12] The court convicted the company’s manager of violating public duties and banned him from holding office for more than nine years. The director of the company that acted as intermediary had, as of June 2023, an arrest warrant issued against him.[13] The Attorney General’s Office said that investigations remain open, and more people may have been implicated.[14] |

Dam Project on the Gualcarque RiverIn March 2019, UFECIC criminally charged 16 people with corruption for irregularities in the permitting process for the construction and operation of the Agua Zarca hydroelectric dam project, on the Gualcarque River, in northwestern Honduras.[15] Prosecutors argued that a Honduran company created in 2009 colluded with officials in several government agencies—including the National Electric Power Company and the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment—to obtain the permit without accurate and complete environmental feasibility studies, and claiming that it would be able to produce more energy than what was feasible. The accusations were based on complaints by the Consejo Cívico de Organizaciones Populares e Indígenas de Honduras (COPINH), an organization led by environmental and Indigenous rights activist Berta Cáceres, who was killed in 2016. COPINH became a plaintiff in the corruption case in August 2021.[16] COPINH argues that the dam concession was granted without obtaining the consent of the Lenca Indigenous community.[17] Honduras has ratified International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention 169, which, among other provisions, recognizes the right of Indigenous people to be consulted about projects on their lands.[18] Though Honduras has not yet approved national legislation to implement that right, Honduras’ Constitution mandates that international treaties that the country has ratified are part of its domestic law.[19] David Castillo, who had controlled the private company that obtained the concession, even as he was serving as a public official at the National Electric Power Company, is one of the defendants in the corruption investigation. In a separate case, Castillo was convicted as a co-conspirator in the killing of Cáceres, and sentenced, in June 2022, to 22 years in prison.[20] The court found that Castillo ordered the killing because of her opposition to the dam. The decision on the trial against Castillo and five other defendants on the corruption case was pending as of June 2023. A court dismissed the charges against the remaining ten, a prosecutor told Human Rights Watch.[21] |

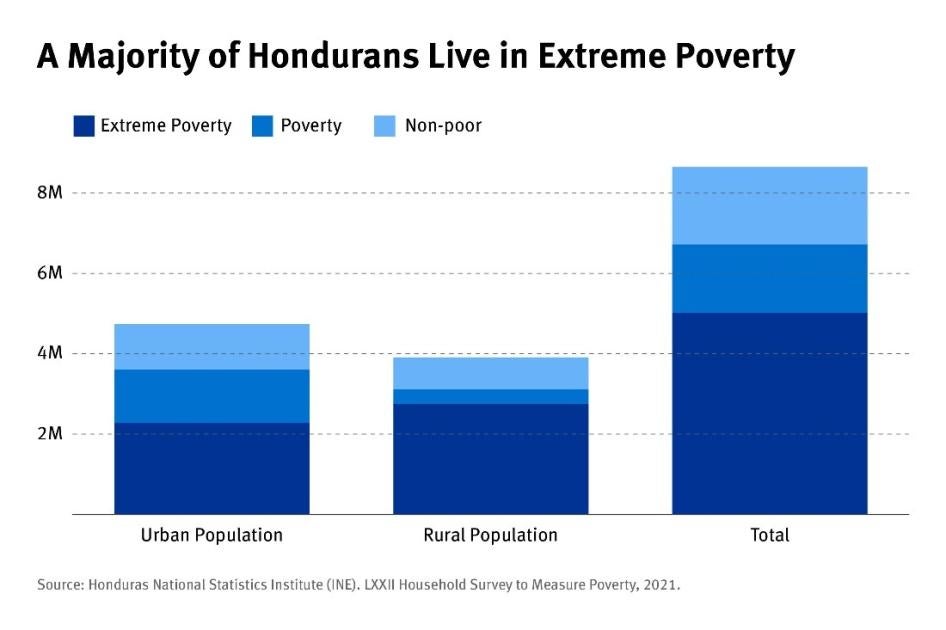

PandoraIn June 2018, the UFECIC charged 38 people, including legislators, public officials, and private citizens, with corruption for diverting almost US$12 million that had been allocated to social projects.[22] The Supreme Court controversially dismissed charges against 32 defendants in February 2022. The projects were meant to support rural Hondurans living in poverty and provide them with training in agriculture and entrepreneurship. Some were specifically aimed at young people, including women. Nearly 80 percent of rural Hondurans live in poverty, and almost all of them in extreme poverty, official data from 2021 shows.[23] In cities, more than 75 percent live in poverty, almost two-thirds of them in extreme poverty, the data show. Prosecutors argued that the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock and the Ministry of Finance directed almost US$12 million to two Honduran nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), supposedly to implement those projects, but instead the money ended up in the hands of public officials and private citizens. Prosecutors tracked the allocation of funds, check trails, bank transfers, and cash withdrawals to show that the two NGOs were functioning as vehicles to receive the funds and divert them to be used for electoral and private purposes. In February 2022, the Supreme Court dismissed charges against 32 defendants.[24] The Attorney General’s Office criticized the decision, saying the court was “protect[ing] one of the most reprehensible acts of corruption in the country's history.” A prosecutor told Human Rights Watch that the Supreme Court issued a general ruling without considering each defendant separately.[25] As of June 2023, three additional defendants had stood trial, with verdicts pending, and there was an extradition process ongoing for three more who were living abroad. |

Arca AbiertaIn December 2018, UFECIC charged 11 legislators and one private citizen with embezzlement, and 9 more individuals as accomplices.[26] Prosecutors argued that the legislators asked the president’s office to allocate almost US$ 1 million, supposedly for social projects, to a Honduran NGO created in 2015. The organization funneled the money back to the legislators, their relatives, or third parties, for personal use, including for shopping at Tegucigalpa’s malls, prosecutors said. The projects that the legislators said the funds would support included fumigation to prevent dengue, a debilitating disease transmitted by mosquitoes that regularly strikes Honduras. There were significant dengue outbreaks in Honduras in 2013, 2015, 2019, and 2022.[27] None of the projects were carried out, prosecutors said. Evidence they presented included the legislators’ requests for funds, along with records of how the funds were allocated, check trails, bank transfers, cash withdrawals, and debit card payments. In November 2022, an appeals court determined that the case could not continue because a law passed after the alleged crimes—Decree 116/2019—requires the Board of Auditors, an official entity charged with auditing public resources, to complete a final report in three years, after which wrongdoers have four years to repay the funds diverted.[28] So, if after seven years, there’s no repayment, the Attorney General’s Office may prosecute. The appeals court freed all defendants. |

International Commission Against Corruption and Impunity

In her inaugural speech on January 27, 2022, President Castro announced that her administration would work with the UN to install an international commission against corruption and impunity in Honduras, one of her main campaign pledges.[29]

Days later, on February 4, Congress passed a law creating CICIH and empowering President Castro to negotiate its operating rules with the UN.[30] The Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced, on February 17, that the Castro administration had sent the UN Secretary-General (UNSG) a request for support in creating CICIH.[31]

It was not until December 15 that the Castro administration and the UNSG signed a memorandum outlining two phases: During the first, the UN and the Honduran government would agree to terms for a team of UN experts to visit the country, and the team would help identify necessary legal reforms to enable the commission’s establishment.[32] During the second, the UNSG would obtain authorization to move forward from an intergovernmental UN body, which is not named in the memorandum but could be the General Assembly. Once that authorization is granted, the UNSG and Honduras would ratify a bilateral agreement, and the commission would be established.

On April 25, 2023, President Castro sent a letter to the UNSG with the conditions under which UN experts could visit Honduras.[33]

The December 2022 memorandum is a positive but very preliminary step towards establishing CICIH. Many crucial matters, essential for its autonomy and independence, have yet to be agreed upon, such as:

- the mechanism to designate who will lead the commission, be its spokesperson, and how the interaction and coordination with various public institutions will be.

- its funding, as the commission must have the necessary resources to work, and not have to compromise, in practice or appearance, its independence.

- the nature of the cases the commission will work on, and how it will operate, alongside local prosecutors, to investigate and prosecute them.

- its mandate to propose and promote legislative and policy changes to strengthen the fight against corruption.

- selection of staff, both local and international, and planning for their security and protection, both while CICIH is in Honduras and once it is gone, to avoid the kind of backlash that nowadays suffer those who worked with the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG).[34]

Obstacles in Honduras’ Legal Framework to Fight Corruption

Several laws Congress passed in recent years have hindered the fight against corruption and reduced transparency and accountability. They include:

- Decree 116/2019, which allows public officials, including legislators, to direct money to third parties, including NGOs, to conduct community projects, a practice that prosecutors argue has enabled corruption.[35] The decree also bars the Attorney General’s Office from investigating such cases for up to seven years: It requires a report from the Board of Auditors, an official entity charged with auditing public resources, which may take up to three years to complete. If the Board finds mismanagement of funds, the decree gives the responsible public official up to four years to repay them.

- Decree 117/2019, which, in sweeping language, bars civil, administrative, or criminal sanctions against legislators for actions taken “in the exercise of their duties as legislators.”[36]

- Decree 57/2020, which requires prosecutors always to request information in writing from public officials and allows seizure of documents only with a judge’s prior authorization if, in a “reasonable time,” public officials do not provide the information previously requested in writing.[37] Combined, these provisions ensure that officials will be alerted of any investigation and possible search, giving them a chance to hide or modify information about the misuse of public funds.

- Decree 93/2021, which weakens the criminal definition of money laundering, making laundering harder to prove in cases when the origin of assets is unknown.[38] The decree has resulted in dismissal of many cases that were under investigation.[39]

- Decree 4/2022, which grants amnesty to people who were public officials during President Manuel Zelaya’s term in office and were charged or convicted for “actions related to the exercise of their public function” after the 2009 coup against Zelaya.[40] This provision came as part of a broader amnesty, lauded by human rights organizations, for people charged or convicted “on political grounds” for protesting or defending land and other rights. But the broad language in the decree could shield corruption, according to anti-corruption groups.[41] The US Department of State said that, as of October 2022, corruption cases against at least 24 defendants had been dismissed pursuant to the amnesty law.[42]

Judicial and Prosecutorial Independence

The Supreme Court is a key institution in the fight against corruption, as it has jurisdiction over cases involving members of Congress and other high-level public officials.[43] But the court for years lacked independence and ruled in ways that furthered the interests of those in power.[44]

New justices are appointed to all 15 seats every seven years. Before this year, the selection process was highly vulnerable to political manipulation.

In July 2022, in preparation for the selection scheduled for January 2023, Congress adopted a law regulating the functioning of the committee in charge of selecting candidates.[45] The law established evaluation standards and advanced transparency, allowing for the participation of civil society and UN agencies as observers. It also required gender parity.

Congress appointed 15 new justices in February 2023.[46] Though, effectively, as in the past, political parties appointed the justices splitting the vacancies among them, in this instance Congress selected the justices from a list prepared by the committee based on merit. They also complied with the gender parity requirement and selected the country’s first Afro-Honduran justice.

Lack of transparency and clear criteria continue to plague selection of lower-court judges and decisions about their careers. One person—the Supreme Court president—has significant power over the selection, promotion, transfer, and discipline of lower-court judges.[47]

The Inter-American Court of Human Rights and the United Nations special rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers have warned that the excessive concentration of power in the Supreme Court is troublesome and that the internal disciplinary system for judges in Honduras lacks independence.[48]

The mechanism to appoint the attorney general and the deputy attorney general likewise lacks transparency and is highly vulnerable to political interference.[49] By constitutional mandate, Congress appoints both, by a two-thirds majority, from a list of five candidates prepared by a nominating committee.[50]

The current attorney general, Óscar Chinchilla, appointed in 2018, was not on the list of five candidates that the nominating committee prepared, in violation of a constitutional provision that mandates that the attorney general be selected from that list.[51]

The ongoing process to select a new attorney general and deputy attorney general should follow constitutional requirements intended to guarantee transparency and integrity in the appointments. Likewise, it is important that the nominating committee apply objective evaluation criteria, publicly and transparently disclose the requirements and selection criteria, and allow for the scrutiny of social sectors and the participation of civil society, in line with international standards.[52]

Recommendations

To the Administration of President Castro and UN Secretary General António Guterres:

- Complete negotiations to establish an independent, autonomous, and efficient international commission with a mandate that includes:

- Investigation and prosecution of individual corruption cases, with a strategy to prioritize high-impact cases.

- Proposal of legislative reforms to strengthen the rule of law and the fight against corruption.

- Training of Honduran prosecutors, judges, police, and others to fight corruption effectively.

- Close collaboration with civil society organizations.

- Based on the experience of similar mechanisms created in other countries, incorporate measures during the negotiations to:

- Ensure the protection of national and international CICIH personnel from possible reprisals for their work, both while the commission is functioning and once its mandate ends.

- Guarantee the independence of the commission to carry out its functions by establishing, among others, a mandate length for the commission and its top officials that is longer than a presidential term, with the possibility of renewal of the mandate.

- Ensure the commission is transparent and accountable through, among other measures, the creation of an independent oversight mechanism.

- Recruit personnel to work in CICIH who provide interdisciplinary expertise to the commission, including political analysis and communications.

- Per the memorandum between the UN and Honduras, work with UN member states to obtain broad support in an intergovernmental UN body to approve UN backing of CICIH.

To President Castro:

- Cooperate with corruption investigations by providing government information about contracts, spending, and other issues of interest to prosecutors.

- Work with Congress to reform the legal framework for fighting corruption, including by introducing bills to abrogate or modify legislation. (See recommendations, below, to Congress.)

- Ensure that all government institutions apply the transparency policy enshrined in the Transparency and Access to Public Information Law,[53] including through routine publication of information of public interest; and ensure that the mechanism that grants the public and the press access to government information works efficiently.

To the Honduran Congress:

- Abrogate or modify legislation that has hindered the fight against corruption, including decrees 116/2019, 117/2019, 57/2020, 93/2021, and 4/2022.

- Pass a law to improve the independence of the judiciary, in accordance with international standards,[54] including by:

- creating a judicial governance system with a fair, transparent, and independent mechanism for disciplinary actions against lower court judges, administered by a body separate from the Supreme Court and with the necessary safeguards to ensure its independence of political and other outside pressure;

- establishing that judges can only be suspended or removed for reasons of incapacity or behavior that renders them unfit to discharge their duties;

- establishing clear rules for the appointment, transfer, and promotion of lower court judges, based on their qualifications and integrity;

- ensuring the prompt appointment of tenured judges; and

- establishing clear rules for distribution of cases among judges to prevent conflicts of interest and vulnerability to internal and external pressures.

- Modify procedures for appointing the attorney general, deputy attorney general, and other high officials to prevent political interference.

- Select the attorney general and the deputy attorney general based on their qualifications, experience, and integrity, through a transparent process based on clear criteria and allowing civil society participation.

To the US, Canadian, European, and Latin American Governments:

- Support efforts to fight corruption in Honduras and commit publicly to providing financial and technical support to CICIH.

[1] United Nations Convention Against Convention, adopted on October 31, 2003, https://www.unodc.org/documents/treaties/UNCAC/Publications/Convention/08-50026_E.pdf (accessed May 4, 2023).

[2] International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, adopted on December 16, 1966, https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-economic-social-and-cultural-rights (accessed May 4, 2023).

[3] Human Rights Watch, “Well Oiled, Oil and Human Rights in Equatorial Guinea,” July 9, 2009, https://www.hrw.org/report/2009/07/09/well-oiled/oil-and-human-rights-equatorial-guinea.

[4] See, for example, Human Rights Watch, “Secret and Unaccountable, The Tribal Council at Lower Brule and its Impact on Human Rights,” January 12, 2015, https://www.hrw.org/report/2015/01/12/secret-and-unaccountable/tribal-council-lower-brule-and-its-impact-human-rights; “'There is No Time Left,' Climate Change, Environmental Threats, and Human Rights in Turkana County, Kenya,” October 15, 2015, https://www.hrw.org/report/2015/10/16/there-no-time-left/climate-change-environmental-threats-and-human-rights-turkana; “'Manna From Heaven'?, How Health and Education Pay the Price for Self-Dealing in Equatorial Guinea”, June 15, 2017, https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/06/15/manna-heaven/how-health-and-education-pay-price-self-dealing-equatorial-guinea.

[5] Honduras’ Ministry of Health, “Situación actual Covid-19. Red de hospitales de la Secretaría de Salud de Honduras,” December 29, 2020, https://www.facebook.com/saludhn/posts/pfbid0V8PyZS8WRPJ8wJ8RWjr2PfBJDVMx3gLwhDJ4ztGfFqU3mfPZWMLtAWi3hDHq8aKal (accessed May 4, 2023).

[6] Consejo Nacional Anticorrupción, “La corrupción en tiempos del Covid-19. Parte VIII: El jugoso negocio de la intermediación, la compra irregular y sobrevalorada de los hospitales móviles por parte de Invest-H,” July 2020, https://www.cna.hn/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/La-corrupcio%CC%81n-en-tiempos-del-COVID-19_Parte-VIII1.pdf (accessed May 4, 2023).

[7] Asociación para una Sociedad más Justa, “Compra de hospitales móviles – Emergencia Covid-19,” June 2020, https://asjhonduras.com/covid19/informe_hospitales.html (accessed May 4, 2023).

[8] Human Rights Watch interview with Suyapa Figueroa, then-President of the Honduran Medical Association, Tegucigalpa, January 26, 2022.

[9] Ibíd.

[10] Transparency International, “Corruption and the coronavirus,” March 18, 2020, https://www.transparency.org/en/news/corruption-and-the-coronavirus (accessed May 4, 2023).

[11] See Artjoms Ivlevs and Timothy Hinks, “Global economic crisis and corruption,” March 2020, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/273250262_Global_economic_crisis_and_corruption (accessed May 4, 2023); Jennifer Haberkorn, “Oversight of $2-trillion coronavirus relief act hasn’t gotten off the ground,” Los Angeles Times, April 20, 2020, https://www.latimes.com/politics/story/2020-04-20/oversight-2-trillion-coronavirus-relief-package (accessed May 4, 2023); Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, “Crime, Corruption, and Coronavirus,” March 24, 2020, https://www.occrp.org/en/coronavirus/ (accessed May 4, 2023).

[12] Honduras’ judiciary, “Tribunal de sentencia en materia de corrupción condena a 10 años 11 meses de reclusión más el pago de millonaria multa a Marco Bográn por compra de hospitales móviles,” June 10, 2022, https://twitter.com/PJdeHonduras/status/1535285991359102976?s=20 (accessed May 4, 2023).

[13] Honduras’ Attorney General’s Office, “El 8 de mayo se emitirá fallo en el caso Hospitales Móviles, con el que MP espera recuperar más de 100 millones de lempiras incautados a Axel López,” April 21, 2023, https://www.mp.hn/publicaciones/mp-disconforme-con-primera-condena-en-el-caso-hospitales-moviles/ (accessed May 4, 2023).

[14] Honduras’ Attorney General’s Office, “MP disconforme con primera condena en el caso Hospitales Móviles,” May 17, 2022, https://www.mp.hn/publicaciones/mp-disconforme-con-primera-condena-en-el-caso-hospitales-moviles/ (accessed May 4, 2023).

[15] Honduras’ Attorney General’s Office, “Requerimiento fiscal,” March 4, 2019, on file at Human Rights Watch.

[16] Consejo Cívico de Organizaciones Populares e Indígenas de Honduras, “Posicionamiento del COPINH ante reintegro como víctima en caso Fraude sobre el Gualcarque,” August 25, 2021, https://berta.copinh.org/2021/08/posicionamiento-del-copinh-ante-reintegro-como-victima-en-caso-fraude-sobre-el-gualcarque/ (accessed May 4, 2023).

[17] Consejo Cívico de Organizaciones Populares e Indígenas de Honduras, “¿De qué se trata el “Fraude Sobre el Gualcarque?,” March 16, 2023, https://twitter.com/COPINHHONDURAS/status/1636465769574703111?s=20 (accessed May 4, 2023).

[18] International Labour Organization, “C169 - Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989 (No. 169),” adopted on June 27, 1989, entered into force on September 5, 1991, ratified by Honduras on March 28, 1995, https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_INSTRUMENT_ID,P12100_LANG_CODE:312314,en (accessed May 4, 2023).

[19] Honduras’ Constitution, https://www.tsc.gob.hn/web/leyes/Constitucion_de_la_republica.pdf (accessed May 4, 2023), article 16.

[20] Honduras’ judiciary, “Sala I con jurisdicción nacional impone una pena de más de 22 años de reclusión al ciudadano Roberto Castillo Mejía por el asesinato de la ambientalista Berta Cáceres,” June 20, 2022, https://twitter.com/PJdeHonduras/status/1538986878610841603?s=20 (accessed May 4, 2023).

[21] Human Rights Watch online interview with Luis Javier Santos, chief prosecutor at UFERCO, March 30, 2023.

[22] Honduras’ Attorney General’s Office, “Requerimiento fiscal,” June 13, 2018, on file at Human Rights Watch.

[23] Honduras’ National Statistics Institute, “LXXII Encuesta Permanente de Hogares de Propósitos Múltiples (2021),” July 2021, https://www.ine.gob.hn/V3/ephpm/ (accessed May 4, 2023).

[24] Honduras’ Attorney General’s Office, “Sala Constitucional notifica fallo que blinda de impunidad a implicados en Caso Pandora,” February 11, 2022, https://www.mp.hn/publicaciones/sala-constitucional-notifica-fallo-que-blinda-de-impunidad-a-implicados-en-caso-pandora/ (accessed May 4, 2023).

[25] Human Rights Watch online interview with Luis Javier Santos, chief prosecutor at UFERCO, March 30, 2023.

[26] Honduras’ Attorney General’s Office, “Requerimiento fiscal,” December 11, 2018, on file at Human Rights Watch.

[27] Médecins Sans Frontières, “Honduras: respondemos a una nueva epidemia de dengue,” March 13, 2019, https://www.msf.es/noticia/honduras-respondemos-una-nueva-epidemia-dengue (accessed May 4, 2023); “Honduras: MSF iniciamos proyecto de emergencia para prevención del dengue en Tegucigalpa,” August 10, 2022, https://www.msf.mx/actualidad/honduras-msf-iniciamos-proyecto-de-emergencia-para-prevencion-del-dengue-en-tegucigalpa/ (accessed May 4, 2023).

[28] Honduras’ judiciary, Tweet from November 14, 2022, https://twitter.com/PJdeHonduras/status/1592277609744060416?s=20 (accessed May 4, 2023).

[29] Jorge Sierra, “Xiomara Castro promete Misión Anticorrupción, consultas populares, derogar ZEDEs y energía gratis,” Proceso Digital, January 27, 2022, https://proceso.hn/xiomara-promete-mision-anticorrupcion-consultas-populares-derogar-zedes-y-energia-gratis/ (accessed May 4, 2023).

[30] La Gaceta, “Decreto No. 4-2022,” published February 4, 2022, https://www.tsc.gob.hn/web/leyes/Decreto-4-2022.pdf (accessed May 4, 2023).

[31] Honduras’ Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Tweet from February 17, 2022, https://twitter.com/CancilleriaHN/status/1494459368087109635?s=20 (accessed May 4, 2023).

[32] Honduras’ Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Tweet from December 15, 2022, https://twitter.com/CancilleriaHN/status/1603556806248304640?s=20 (accessed May 4, 2023).

[33] Honduras’ government, Tweet from April 26, 2023, https://twitter.com/GobiernoHN/status/1651261738522640389?s=20 (accessed May 4, 2023).

[34] Human Rights Watch, “Guatemala: Events of 2022,” January 2023, https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2023/country-chapters/guatemala.

[35] La Gaceta, “Decreto No. 116-2019,” published October 18, 2019, https://www.tsc.gob.hn/web/leyes/Decreto-116-2019.pdf (accessed May 4, 2023).

[36] La Gaceta, “Decreto No. 117-2019,” published October 18, 2019, https://www.tsc.gob.hn/web/leyes/Decreto-117-2019.pdf (accessed May 4, 2023).

[37] La Gaceta, “Decreto No. 57-2020,” published October 13, 2020, https://www.tsc.gob.hn/web/leyes/Decreto-57-2020.pdf (accessed May 4, 2023).

[38] La Gaceta, “Decreto No. 93-2021,” published November 1, 2021, https://www.tsc.gob.hn/web/leyes/Decreto_93-2021.pdf (accessed May 4, 2023).

[39] See, for example, “Reforma a Ley de Lavado deja en libertad a 45 socios de narcos,” El Heraldo, October 25, 2022, https://www.elheraldo.hn/honduras/reforma-ley-de-lavado-deja-libertad-45-socios-narcos-los-cachiros-valle-valle-KD10640857 (accessed May 4, 2023).

[40] La Gaceta, “Decreto No. 4-2022,” published February 4, 2022, https://www.tsc.gob.hn/web/leyes/Decreto-4-2022.pdf (accessed May 4, 2023). See also Human Rights Watch, “After the Coup: Ongoing Violence, Intimidation, and Impunity in Honduras,” December 20, 2010, https://www.hrw.org/report/2010/12/20/after-coup/ongoing-violence-intimidation-and-impunity-honduras.

[41] Consejo Nacional Anticorrupción, “Delitos que pretenden ser perdonados por medio de decreto de amnistía,” February 3, 2022, https://www.cna.hn/delitos-que-pretenden-ser-perdonados-por-medio-de-decreto-de-amnistia/ (accessed May 4, 2023).

[42] United States Department of State, “2022 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Honduras,” March 20, 2023, https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-country-reports-on-human-rights-practices/honduras/ (accessed May 4, 2023).

[43] Honduras’ Constitution, https://www.tsc.gob.hn/web/leyes/Constitucion_de_la_republica.pdf (accessed May 4, 2023), article 313; Honduras’ Criminal Procedure Code, https://wipolex-res.wipo.int/edocs/lexdocs/laws/es/hn/hn027es.pdf (accessed May 4, 2023), articles 414 to 417.

[44] See, for example, Human Rights Watch, “Honduras: Select Supreme Court Based on Merit,” October 4, 2022, https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/10/04/honduras-select-supreme-court-based-merit.

[45] La Gaceta, “Decreto No. 74-2022,” published July 20, 2022, https://www.tsc.gob.hn/web/leyes/Decreto-74-2022.pdf (accessed May 4, 2023).

[46] La Gaceta, “Decreto No. 2-2023,” published February 17, 2023, https://www.tsc.gob.hn/web/leyes/Decreto-2-2023.pdf (accessed May 4, 2023).

[47] Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, “Situation of Human Rights in Honduras,” August 27, 2019, https://www.oas.org/en/iachr/reports/pdfs/honduras2019-en.pdf (accessed May 4, 2023), paragraph 84; United Nations Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, “Visit to Honduras,” A/HRC/44/47/Add.2, June 2, 2020, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G20/124/46/PDF/G2012446.pdf?OpenElement (accessed May 4, 2023), paragraph 33.

[48] Inter-American Court of Human Rights, “Case of López Lone et. al. v. Honduras,” judgement of October 5, 2015, Series C No. 302, https://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/casos/articulos/seriec_302_ing.pdf (accessed May 4, 2023); United Nations Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, “Visit to Honduras,” A/HRC/44/47/Add.2, June 2, 2020, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G20/124/46/PDF/G2012446.pdf?OpenElement (accessed May 4, 2023), paragraph 33.

[49] Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, “Situation of Human Rights in Honduras,” August 27, 2019, https://www.oas.org/en/iachr/reports/pdfs/honduras2019-en.pdf (accessed May 4, 2023), paragraph 23; United Nations Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, “Visit to Honduras,” A/HRC/44/47/Add.2, June 2, 2020, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G20/124/46/PDF/G2012446.pdf?OpenElement (accessed May 4, 2023), paragraph 51.

[50] Honduras’ Constitution, https://www.tsc.gob.hn/web/leyes/Constitucion_de_la_republica.pdf (accessed May 4, 2023), article 233.

[51] Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, “Situation of Human Rights in Honduras,” August 27, 2019, https://www.oas.org/en/iachr/reports/pdfs/honduras2019-en.pdf (accessed May 4, 2023), paragraph 23.

[52] Joint statement by Human Rights Watch, the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), the Center for Justice and International Law (CEJIL), the Due Process of Law Foundation (DPLF), RFK Human Rights, and the Latin America Working Group (LAWG), “Nominating Board in Honduras must guarantee independence and transparency in election of Attorney General,” June 1, 2023, https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/06/01/nominating-board-honduras-must-guarantee-independence-and-transparency-election.

[53] La Gaceta, “Decreto No. 170-2006,” published December 30, 2006, https://www.tsc.gob.hn/web/leyes/Ley_de_Transparencia.pdf (accessed May 4, 2023).

[54] Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary, adopted in 1985, https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/basic-principles-independence-judiciary (accessed May 4, 2023).