Memorandum of Support

Human Rights Watch urges New York lawmakers to co-sponsor the Eliminate Mandatory Minimums (S.7871/ A.9166),[1] Second Look (S.7872/A.8894),[2] and Earned Time Act (S.7873A/ A.8462B).[3]

Human Rights Watch is an international non-profit organization dedicated to investigating and monitoring violations of basic human rights throughout the world, including in the United States.[4] Human Rights Watch conducts investigations of human rights abuses in around 100 countries. Our US Program focuses on, among other issues, international human rights law compliance within the criminal legal system.

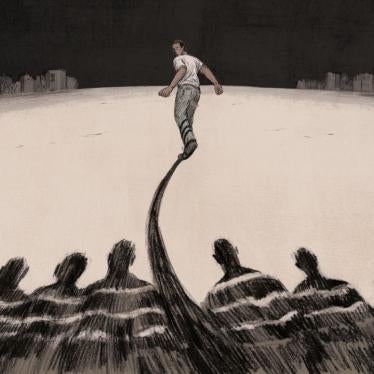

Over the past half-century, New York’s sentencing laws have helped to drive a crisis of mass incarceration that has done enormous harm to Black and brown communities. Today, over 30,000 people are incarcerated in New York state prisons[5]—a number that is down from its peak in 1999 but significantly higher than it was in the mid-1970s.[6] Over 70 percent of those incarcerated are Black or brown.[7] In 2019 in New York, the Black to white racial disparity in incarceration rates was a ratio of 7.9 to 1.[8]

New York’s sentencing laws result in serious miscarriages of justice. In New York State, 98 percent of felony arrests that end in convictions are the result of plea deals—not trial.[9] In many cases, the use of mandatory minimums increases the likelihood that these pleas will be coerced. By requiring a judge to hand down a minimum prison sentence based solely on the prosecutor’s charging decision, mandatory minimums transfer sentencing power from judges to prosecutors and grant prosecutors unfair and overwhelming leverage in plea negotiations, undermining the constitutional right to trial.[10]

In many cases, these harsh sentences are imposed without judges having any opportunity to review and consider mitigating or extenuating circumstances and with incarcerated people having limited capacity to earn good time credits[11] or get their sentences reduced.

It is possible to end this practice in in New York. We urge the legislature to pass the Eliminate Mandatory Minimums Act, Second Look Act, and Earned Time Act and stand for Communities Not Cages.[12]

THE ELIMINATE MANDATORY MINIMUMS ACT

Mandatory minimum sentencing drives mass incarceration. It limits the ability of judges to consider the facts of an individual case and grants outsized power to prosecutors to coerce plea deals. The Eliminate Mandatory Minimums Act (S.7871/ A.9166) would help to address this by ending mandatory minimum sentences, including New York’s two and three-strike laws, and allowing judges to consider individual mitigating circumstances in sentencing determinations. It would also create a presumption against incarceration for any potential sentence of a year or more, requiring judges to hold a hearing before any such sentence can be imposed. At that hearing, prosecutors would have to show by clear and convincing evidence that nothing other than imprisonment will address the unlawful behavior and promote community safety before any period of incarceration can be imposed. This will help re-orient the system toward one that considers alternatives to incarceration much more frequently.

THE SECOND LOOK ACT

As the New York prison population has declined in recent years, the share of those serving longer sentences and those 50 or older has risen. Nearly half of those incarcerated are serving sentences of at least ten years or more, and nearly a quarter are serving sentences of at least 20 years or more.[13] These numbers reflect the influence of lengthy minimum terms.[14] Many of those serving these sentences were convicted of crimes they committed as young people and are now so cognitively impaired they may not even remember what they did or why they are in prison.[15] Echoing national trends, many also struggle with chronic health conditions.[16] The share of people 50 or over in New York state prisons has more than doubled from 2008 to 2021.[17] Prisons have become inadequate hospitals and long-term care facilities for thousands of sick and aging people.[18]

Under current law, sentencing judges do not have an opportunity to review and reconsider excessive sentences. The Second Look Act (S.7872/A.8894) would allow this to happen, permitting incarcerated people to petition for resentencing after serving 10 years and judges to reduce sentences after considering a variety of factors. For those found to be eligible for resentencing, this could mean an opportunity to return to their families and communities, and to rebuild their lives. Nationally, second look bills are gaining momentum. Illinois, Louisiana, Maryland, Oregon, and the District of Columbia,[19] all passed such bills, and they have been proposed in an additional 22 states.[20] In 2019, US Senator Cory Booker proposed the Second Look Act in Congress.[21]

THE EARNED TIME ACT

Despite clear research[22] that longer prison terms do little to deter crime[23] and have no effect on the level of crime in society,[24] New York has continued to allow them to be imposed and provided few avenues for them to be revisited. In response to the federal 1994 Crime Bill, which incentivized states to institute harsher sentencing laws,[25] New York State slashed programs for incarcerated people and dramatically limited the time people could earn off their sentences. This included eliminating financial aid for incarcerated college students and ending most college-in-prison programs.[26] New York also restricted access to merit time based on conviction type, eliminating key opportunities for rehabilitative programming, and earned time for thousands of New Yorkers each year. New York is substantially behind other states—including traditionally conservative states—in allowing incarcerated people to earn time off their sentences through good behavior, completing programming, or otherwise demonstrating rehabilitation. For example, Alabama, Nebraska, and Oklahoma all permit incarcerated people to earn over 50 percent good time.[27] The Earned Time Act (S.7873A/ A.8462B) will strengthen and expand the ability to earn “good time” and “merit time,” incentivizing personal transformation and creating the ability for families to be reunited.

Human Rights Watch joins over 125 organizations across New York including civil rights organizations, racial justice groups, labor unions, community groups, legal service providers, and incarcerated and formerly incarcerated community members in support of these necessary and long overdue bills. We urge our legislature to pass the Eliminate Mandatory Minimums (S.7871/ A.9166), Second Look (S.7872/A.8894), and Earned Time Act (S.7873A/ A.8462B).

Sincerely,

Olivia Ensign

Senior Advocate, US Program

Phone: (646) 984-2015

Email: ensigno@hrw.org

Laura Pitter

Deputy Director, US Program

Phone: (917) 450 4361

Email: pitterl@hrw.org

[1] New York State Senate, “Eliminate Mandatory Minimums Act, S.7871” January 18, 2022, https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2021/S7871#:~:text=This%20legislation%20would%20eliminate%20mandatory,the%20Rockefeller%20Drug%20Law%20era (accessed April 19, 2022).

[2] New York State Senate, “Second Look Act, S.7872,” January 18, 2022, https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2021/S7872 (accessed April 19, 2022).

[3] New York State Senate, “Earned Time Act, S.7873A,” January 18, 2022, https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2021/s7873 (accessed April 19, 2022).

[4] Human Rights Watch, “Home Page,” https://www.hrw.org/.

[5] New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision, “DOCCS Fact Sheet,” March 1, 2022, https://doccs.ny.gov/system/files/documents/2022/03/doccs-fact-sheet-march-2022.pdf.

[6] Marvin Mayfield, “A Century after Attica, Prisoner’s Demands Have Not been Met,” New York Daily News, Sept. 8, 2021 https://www.nydailynews.com/opinion/ny-oped-half-century-attica-20210908-drus54lc25h6ribz6szam2rhfa-story.html#:~:text=In%201970%2C%20New%20York%20State,of%2066%20per%20100%2C000%20residents (accessed April 19, 2022), citing Historical Corrections Statistics in the United States 1950-1984, United States Department of Justice, Bureau of Statistics, December 1986, (https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/hcsus5084.pdf); Prison Policy Initiative, “State Prison Population In New York 1978 to 2012,” 2014, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/graphs/incsize/NY.html (accessed April 19, 2022).

[7] New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervisor, “Profile of Under Custody Population As of January 1, 2019,” https://doccs.ny.gov/system/files/documents/2021/05/under-custody-report-2019.pdf (accessed April 19, 2022) (hereinafter “Profile of Under Custody Population in New York” report).

[8] The Sentencing Project, “State by State Data,” 2019, https://www.sentencingproject.org/the-facts/#map?dataset-option=BWR (accessed April 19, 2022).

[9] Beth Schwartzapfel, “Defendants Kept in the Dark About Evidence, Until It’s Too Late,” New York Times, August 7, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/07/nyregion/defendants-kept-in-the-dark-about-evidence-until-its-too-late.html?_r=0 (accessed April 19, 2022).

[10]Alison Siegler, “End Mandatory Minimums,” Brennan Center for Justice, October 18, 2021, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/end-mandatory-minimums#:~:text=Long%20sentences%20also%20make%20it%20more%20difficult%20for,neither%20diminish%20public%20safety%20nor%20increase%20drug%20abuse (accessed April 19, 2022); See also, Human Rights Watch, An Offer You Can’t Refuse: How US Federal Prosecutors Force Drug Defendants to Plead Guilty (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2013), https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/us1213_ForUpload_0_0_0.pdf, for an understanding of the ways this plays out in the federal system.

[11] National Conference of State Legislatures, “Good Time Earned Time Policies for State Prison Inmates,” January 2016, https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/misc/lc/study/2016/1495/030_august_31_2016_meeting_10_00_a_m_room_412_east_state_capitol/memono4g (accessed April 19, 2022).

[12] Community Not Cages, Home Page, https://www.communitiesnotcagesny.org/ (accessed April 19, 2022).

[13] New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision, “Incarcerated Profile Report,” November 1, 2021, https://doccs.ny.gov/system/files/documents/2021/12/november-1-2021-incarcerated-individual-profile.pdf (accessed April 8, 2022), p. 8 (available by keyword search for “Incarcerated Profile Report” at https://doccs.ny.gov/research-and-reports)

[14] “Profile of Under Custody Population in New York” report, supra, p. 16 (Though New York prison population has dropped from 47,459 to 31,262 since this report was published, the influence of lengthy prison terms has remained and in fact become more pronounced since people serving less time have mostly benefited from policies aimed at reducing the number of people incarcerated).

[15] “Testimony of Jose Saldana and Dave George, Release Aging People in Prison,” Presented Before Members of the New York Legislature 2019 Public Protection Budget Hearing, January 29, 2019, https://www.nysenate.gov/sites/default/files/testimony_given_by_the_release_aging_people_hi_prison-rapp_campaign.pdf (accessed April 19, 2022).

[16] U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs Bureau of Statistics, Special Report, February 2014, Medical Problems of State and Federal Prisoners and Jail Inmates, 2011-12, https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/mpsfpji1112.pdf (accessed April 12, 2022); See also Columbia University Center for Justice, “New York State’s New Death Penalty: The Death Toll of Mass Incarceration in a Post Execution Era,” October 2021, https://centerforjustice.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/content/New%20York%27s%20New%20Death%20Penalty%20Report.pdf (accessed April 12, 2022); Human Rights Watch, Old Behind Bars: The Aging Prison Population in the United States (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2012), https://www.hrw.org/report/2012/01/27/old-behind-bars/aging-prison-population-united-states.

[17] Office of the New York State Comptroller, New York State’s Aging Prison Population, Share of Older Adults Keeps Rising, January 2022, https://doccs.ny.gov/system/files/documents/2021/05/under-custody-report-2019.pdf (accessed April 19, 2022), p. 1.

[18] Victoria Law, “An Overhaul of Prison Health Care Is Long Overdue,” The Nation, March 17, 2022, https://www.thenation.com/article/society/correctional-health-care/ (accessed April 12, 2022); Office of the New York State Comptroller, New York State’s Aging Prison Population, Share of Older Adults Keeps Rising, January 2022, https://doccs.ny.gov/system/files/documents/2021/05/under-custody-report-2019.pdf; https://www.osc.state.ny.us/files/reports/pdf/aging-prison-population-2022.pdf (accessed April 19, 2022).

[19] DC Corrections Information Council, “DC Council Passes Second Look Amendment Act of 2019,” May 19, 2021, https://cic.dc.gov/release/dc-council-passes-second-look-amendment-act-2019 (accessed April 19, 2022).

[20] Justice Roadmap, “Second Look Act,” https://justiceroadmapny.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/CNC-Second-Look-Act.pdf (accessed April 19, 2022).

[21] United States Congress, “S.2146 - Second Look Act of 2019,” https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/2146 (accessed April 19, 2022).

[22] Anthony Doob and Cheryl Marie Webster, “Sentence Severity and Crime: Accepting the Null Hypothesis,” Crime and Justice 30 (2003): 143–195, accessed April 19, 2022, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1147698 (accessed April 19, 2022).

[23] Marc Mauer, “Long-Term Sentences: Time to Reconsider the Scale of Punishment, The Sentencing Project,” https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/long-term-sentences-time-reconsider-scale-punishment/ (accessed March 15, 2022) (“’[t]he evidence in support of the deterrent effect of the certainty of punishment is far more consistent and convincing than for the severity of punishment’ and that ‘the effect of certainty rather than severity of punishment reflect[s] a response to the certainty of apprehension,’” citing Daniel Nagin, “Deterrence in the Twenty-First Century: A Review of the Evidence,” Carnegie Melon University, 2018, accessed April 19, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1184/R1/6471200.v1; Anthony Doob and Cheryl Marie Webster, “Sentence Severity and Crime: Accepting the Null Hypothesis,” Crime and Justice 30 (2003): 143–195, accessed April 19, 2022, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1147698 (accessed April 19, 2022).

[24] Anthony Doob and Cheryl Marie Webster, “Sentence Severity and Crime: Accepting the Null Hypothesis,” Crime and Justice 30 (2003): 143–195, accessed April 19, 2022, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1147698 (accessed April 19, 2022).

[25] Center for American Progress, “The 1994 Crime Bill Continues to Undercut Justice Reform—Here’s How to Stop it,” March 26, 2019, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/1994-crime-bill-continues-undercut-justice-reform-heres-stop/ (accessed April 19, 2022).

[26] Prison Policy Initiative, “Since You Asked: How did the 1994 Crime Bill Affect Prison College Programs?” August 22, 2019, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2019/08/22/college-in-prison/ (accessed April 19, 2022).

[27] National Conference of State Legislatures, “Good Time Earned Time Policies for State Prison Inmates,” January 2016, https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/misc/lc/study/2016/1495/030_august_31_2016_meeting_10_00_a_m_room_412_east_state_capitol/memono4g (accessed April 19, 2022).