(New York) – Canada, France, Germany, and Sweden are four of only five countries that claim to have a “feminist foreign policy.” Each of them have also been deeply involved in Afghanistan, where the Taliban’s rollback of women’s rights poses a unique challenge for them.

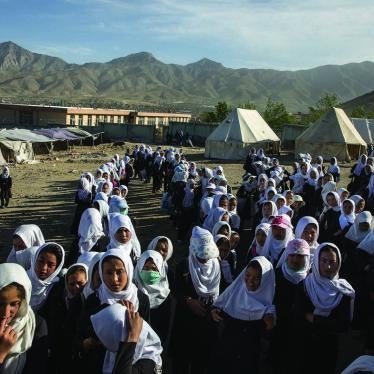

When the Taliban gained control of Afghanistan on Aug. 15, 2021, the consequences for women and girls were brutal and immediate. The Taliban appointed an all-male cabinet. They abolished the Ministry of Women’s Affairs and gave its building to the reinstated Ministry of Vice and Virtue. They banned women from most jobs, except in the education and health sectors — teaching girls and providing healthcare to women. They banned girls from secondary education. They blocked women from leaving the country alone, and systematically destroyed the system of shelters that existed in provincial capitals across much of the country. They issued new rules for how women and girls must dress and behave and are brutally enforcing these rules throughout the country.

Why are these feminist foreign policy countries failing Afghan women when they need them the most?

The Disconnect

Beginning with Sweden in 2014, a growing list of countries proclaimed that they have a “feminist foreign policy” — though whether or not these countries have such a foreign policy is a different matter. What is a feminist foreign policy? According to the Swedish government, a feminist foreign policy “means applying a systematic gender equality perspective throughout the whole foreign policy agenda.”

If feminist foreign policy does not mean standing up for Afghan women and girls in this crisis, it begs the question of what feminist foreign policy means.

There are pragmatic reasons to pursue a feminist foreign policy. As Germany’s former foreign minister wrote in 2020, “Numerous studies demonstrate that societies in which women and men are on equal footing are more secure, stable, peaceful, and prosperous.” Feminist foreign policy recognizes that you cannot have security when half the population is oppressed and living in fear — as is the case in Afghanistan now. Canada’s then foreign minister echoed this, noting that a feminist foreign policy “produces tangible and measurable results.” He added that the goal is removing the obstacles to women’s “full emancipation, to their leadership.”

All four countries committed to a feminist foreign policy have sent troops to Afghanistan during the past 20 years. In late 2011, as the number of US soldiers peaked during the Obama administration, Canada had almost 3,000 troops in Afghanistan, France almost 4,000, Germany over 4,000, and Sweden 500. These four countries joined the fight in Afghanistan to assist their ally, the US, in the wake of the 9/11 attacks. The US highlighted the situation of women and girls under the Taliban as troops were deployed, and several of the “feminist foreign policy” countries also made this link at some point. In 2010, a Swedish politician said, “Swedish involvement strengthens commitment to human rights, good governance, and the promotion of women’s safety, influence, and participation.” A French statement described the presence of French troops in Afghanistan as “improving the position of women in society.”

Time for Feminist Foreign Policy to Step Up

The international response to the human rights and humanitarian crises that have unfolded in Afghanistan since August 2021 has been poor. It has lacked urgency, and there is little sign of an effective coordinated plan, let alone one that prioritizes protecting the rights of Afghan women and girls. On the contrary, some governments pandered to the Taliban by sending all-male delegations to meet them. The US, which played a dominant role in the international involvement in Afghanistan over the last 20 years, has seemed uninterested in providing leadership, and has harmed its credibility on human rights by imposing measures that have helped drive a humanitarian crisis that has left 95% of Afghan households hungry.

Other leadership is urgently needed, and the countries committed to feminist foreign policy should come together to provide it. Afghanistan today is a women’s rights crisis like no other. Women in every country are still having to fight for equality, and rollbacks of women’s rights are happening in several places — including brutal sexual violence in Ethiopia, moves to ban abortion in the US, an election in South Korea where candidates competed to lure “anti-feminist” men, and attacks on women’s rights activists in Poland. But nowhere have we seen the wholesale intentional destruction of the rights of women and girls that is underway in Afghanistan right now, under the misogynistic eye of the Taliban. Correction — the last time we saw such devastation of women’s rights was in 1996 to 2001, when the Taliban were last in power.

Together Canada, France, Germany, and Sweden should develop a concrete strategy for how the international community can stand up for the rights of Afghan women and girls and lead efforts to end the widespread abuses they’re experiencing under the Taliban once again. Then, they should engage as many other countries as possible in this effort. We see from watching the Taliban that they do respond to international pressure; governments around the world can and should press them to respect women’s rights, and such pressure will be most effective if it is coordinated.

If feminist foreign policy does not mean standing up for Afghan women and girls in this crisis, it begs the question of what feminist foreign policy means — and risks the conclusion: not much. Countries committed to feminist foreign policy owe it to Afghan women to lead a vigorous response to the attack on their rights.