(Nairobi) – Eritrean government forces and Tigrayan militias have committed killings, rape, and other grave abuses against Eritrean refugees in Ethiopia’s Tigray region, Human Rights Watch said today. All warring parties should cease attacks against refugees, stay out of refugee camps, and facilitate the delivery of humanitarian aid.

Between November 2020 and January 2021, belligerent Eritrean and Tigrayan forces alternatively occupied the Hitsats and Shimelba refugee camps that housed thousands of Eritrean refugees, and committed numerous abuses. Eritrean forces also targeted Tigrayans living in communities surrounding the camps. Fighting that broke out in mid-July in Mai Aini and Adi Harush, the two other functioning refugee camps, again left refugees in urgent need of protection and assistance.

“Eritrean refugees have been attacked both by the very forces they fled back home and by Tigrayan fighters,” said Laetitia Bader, Horn of Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “The horrific killings, rapes, and looting against Eritrean refugees in Tigray are evident war crimes.”

Since January, Human Rights Watch has interviewed 28 Eritrean refugees: 23 former residents of Hitsats camp and 5 former residents of Shimelba camp, and 2 residents of the town of Hitsats who had witnessed the abuses by Eritrean forces and local Tigrayan militia. Human Rights Watch also interviewed aid workers and analyzed satellite imagery.

Human Rights Watch sent letters summarizing the findings and requesting further information to Ethiopia’s Agency for Refugees and Returnees Affairs (ARRA), the United Nations refugee agency (UNHCR), Eritrea’s permanent mission to the United Nations, and other international organizations in Geneva. Responses from ARRA and UNHCR are included below. Eritrea did not respond.

On November 19, Eritrean forces arrived in the town of Hitsats and indiscriminately killed several residents. They occupied and pillaged the town and took over the refugee camp. Some refugees took part in the looting, contributing to community tensions.

On November 23, Tigrayan militia entered Hitsats camp and attacked refugees near the camp’s Orthodox church. Clashes between the militia fighters and Eritrean soldiers ensued in and around the camp, lasting several hours. Nine refugees were killed and 17 badly injured.

One refugee said that Tigrayan militia fighters killed her husband as their family tried to seek shelter inside the church: “My husband had our 4-year-old on his back and our 6-year-old in his arms. As he came back to help me enter the church, they shot him.”

Two dozen residents in Hitsats town were also reportedly killed during and after the clashes that day. The Tigrayan militia retreated from Hitsats after the fighting.

Eritrean forces later detained approximately two dozen refugees in the camp and took them away in military vehicles. Their whereabouts have not been revealed. Eritrean forces also removed the 17 injured refugees from the camp, taking at least one – and likely others – back to Eritrea, ostensibly for treatment.

The Eritrean forces withdrew from the camp in early December. Tigrayan forces returned on the evening of December 5, shooting into the camp, and sending hundreds of refugees fleeing. In the ensuing days, Tigrayan militia attacked, arbitrarily detained, and sexually assaulted some of the refugees who had fled, notably around Zelazle and Ziban Gedena, north of Hitsats. They then marched the refugees back to Hitsats.

“I am a double victim,” said a 27-year-old woman whom Tigrayan militia fighters raped along with her 17-year-old sister while they fled Hitsats. “Both in Eritrea, and now, here [in Ethiopia], I am not protected.”

In Hitsats, Tigrayan militias and special forces, and members of an unidentified armed Eritrean group, arbitrarily detained hundreds of refugees, apparently to identify refugees who collaborated with the Eritrean forces or who were responsible for looting in the town.

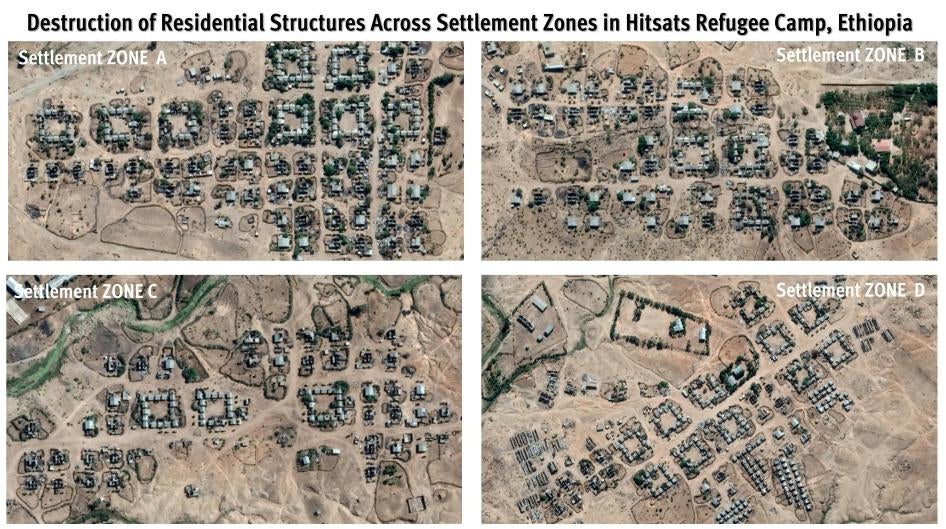

On January 4, following heavy clashes near the camp, Tigrayan forces withdrew from Hitsats. The Eritrean forces returned and ordered all remaining refugees to leave along the main road toward Eritrea. Between January 5 and 8, Eritrean forces destroyed and burned shelters and humanitarian infrastructure in the camp, leaving significant parts of the camp in ruins.

Before and after satellite imagery collected on January 5 and 6, 2021, shows the progressive expansion of the burn scars in Hitsats refugee camp, in Ethiopia’s northern Tigray region. As of January 6, active fires and smoke plumes are visible over the humanitarian infrastructure located on the northeastern part of the camp. Satellite imagery © Planet Labs Inc.

Most refugees then faced an arduous days-long trek to the Ethiopian town of Sheraro and the contested border town of Badme, then under Eritrean control. Refugees said that once there, many felt they had no choice but to return to Eritrea, despite the risks of being detained and facing indefinite forced conscription. Witnesses said hundreds boarded buses headed to Eritrea in January.

Other refugees managed to escape back into Ethiopia, some toward urban areas or the two still-functioning Eritrean refugee camps in southern Tigray, Mai Aini, and Aid Harush. UNHCR reported that 7,643 out of the 20,000 refugees known to have been in Hitsats and Shimelba camps in October 2020 are unaccounted for as of late August 2021. Many of the refugees that have been accounted for fled to Addis Ababa, the Ethiopian capital, but neither the Ethiopian government nor international partners have provided any assistance to date. Refugees who are not receiving assistance are more vulnerable to further abuse, including exploitation, Human Rights Watch said.

“For years, Tigray was a haven for Eritrean refugees fleeing abuse, but many now feel they are no longer safe,” Bader said. “After months of fear, abuse, and neglect, Ethiopia, with support from its international partners, should ensure that all Eritrean refugees have immediate access to protection and assistance.”

For more information and accounts from witnesses, an overview of Ethiopia’s international legal obligations, and recommendations, please see below.

Eritrean Refugees in the Tigray Region

As of October 2020, Ethiopia hosted approximately 149,000 registered Eritrean refugees. Many were in the northern Tigray region, bordering Eritrea, in four camps, with approximately 20,000 in Hitsats and Shimelba in northwestern Tigray and about 31,000 in Mai Aini and Adi Harush camps in southern Tigray.

Ethiopia has a long history of providing group (“prima facie”) recognition to Eritreans fleeing persecution, forced conscription, and other rights abuses in their country. But in January 2020, Ethiopia’s Agency for Refugees and Returnees Affairs (ARRA) stopped registering some categories of new arrivals, including unaccompanied children.

In March 2020 the Ethiopian authorities announced that they would close Hitsats camp. In February 2021 following the fighting between Eritrean forces and Tigrayan armed groups, ARRA stated that Hitsats and Shimelba had been closed.

Hitsats was the newest of the four camps. It was established in 2013 because the others were congested. Hitsats was in a remote and harsh area next to the small town of Hitsats, with little delineation between it and the local community.

For almost five months after the start of the conflict in November 2020, UNHCR and other humanitarian agencies were unable to access Hitsats and Shimelba camps due to insecurity and federal government restrictions. When UNHCR visited the camps in late March, they found them destroyed and empty of refugees.

Eritrean Military’s Killings, Looting in Hitsats Town (November 19 to 23)

On November 19, Eritrean forces arrived in Hitsats, clashed with local Tigrayan forces, and took control of the town and neighboring refugee camp.

Human Rights Watch received credible reports of the killings of at least 31 people in and around Hitsats town between November 19 and 23, but the actual number is most likely significantly higher. A local organization documented and shared the names of 26 people, predominantly from one family, who were all killed on November 23. “All houses were searched by Eritrean troops, and in every house, people were killed,” one resident said. “A friend of mine, Yenialeman Geday Mehari, and her three siblings were killed in their home near the police station.”

At least four of five Ethiopian staff members of humanitarian organizations working in Hitsats were also among those killed in Hitsats between November 19 and 23, humanitarian groups said.

Eritrean forces initially refused to let the community bury their dead. “We heard that the priests were begging to bury them,” a humanitarian worker said. “But [the Eritrean forces] told them to leave the bodies.”

Eritrean soldiers also looted Hitsats town for several days following their takeover, in some cases accompanied by refugees, witnesses said. “They [the Eritrean soldiers] were looting everything, including sugar, jewels, and water from the shops. They butchered the animals.” one refugee said. A local resident saw some refugees pointing out the houses of militia members and members of the town’s administration to the Eritrean forces during house-to-house searches.

Refugees Killed During Fighting in Hitsats Camp (November 23)

There was no fighting in Hitsats camp in the initial days of the Eritrean occupation. The Eritrean forces set up tents inside the camp and established bases at the UNHCR, ARRA, and other humanitarian offices, where they also looted humanitarian equipment. Refugees said soldiers pressured them to return to Eritrea, warning them that they would not be safe in the camp and that the host community was planning to kill them.

On November 23, at around 6 a.m., heavy fighting broke out in Hitsats town, witnesses said. Mid-morning, Tigrayan militia armed with Kalashnikov assault rifles, recognized by some refugees as town residents, entered the refugee camp from at least two directions and started shooting at refugees around the camp’s Orthodox church.

A 28-year-old refugee said three Tigrayan militia fighters stopped him along with two friends and his relative as they headed to church for services:

They didn’t give us much time. They said: “Your ‘shabia’ [Eritrean forces] are killing us and you have the luxury of going to church.” My cousin was the first person injured, not a serious injury at first, but then he tried to escape, and they shot him again. This is when I fled toward the church. Once inside [with other refugees], we locked the door. Thankfully [the militia fighters] didn’t enter.

Several witnesses said that a small contingent of Eritrean forces in the camp fired back at the Tigrayan militiamen.

Nine refugee men were killed, and at least 17 refugees seriously injured, including one woman and a young man who suffered spinal cord damage.

As the clashes continued, Eritrean reinforcements arrived. Two refugees said that the Eritrean forces fired mortar rounds from outside the camp. Satellite imagery recorded on November 23 at 10:39 a.m. shows signs of burning inside the compound of the camp’s high school, and another fire is detected at 1:36 p.m. on a hill, east of the camp.

By early afternoon, the Tigrayan militia forces had fled the camp and town.

After the fighting ended, a refugee who worked at the health clinic on the outskirts of the camp went to the clinic where shots by militiamen had been fired and said he found the body of his colleague, Yonas Kinfe, another refugee, in the toilet: “He had been shot in the forehead.”

Camp residents set up a makeshift clinic in a playground. The cousin of the 27-year-old man who was the first person shot outside the church said his cousin had been shot three times but survived: “The third bullet was hardest to get out. There was no anesthetic; it was horrific. He screamed so much.”

After a few days, Eritrean forces took the injured refugees away, reportedly back to Eritrea. “They told us that they would be taken to Barentu [a town in northwest Eritrea],” a refugee nurse said. “No one was happy about being taken to Eritrea. In particular, the boy with the spinal cord injury, he really didn’t want to go. He complained a lot, but there was no other option.”

The cousin of the 27-year-old injured man still has no news about his relative. “One morning I went back to the tents, and he had disappeared. I was told he had been taken for treatment, but no one told me where. I asked my relatives back in Eritrea, but they had no news. I continue to pray.”

Enforced Disappearances of Refugees by Eritrean Forces (Late November)

On November 26 following the violence inside Hitsats camp, Eritrean forces called the refugees to a meeting and told them to leave the camp. “The meeting was short, no questions asked,” said a refugee who was in attendance. “It was just an order.” Most refugees reportedly ignored the order to leave.

After the meeting, Eritrean forces detained between 20 and 30 refugees, who were reportedly identified on a list of refugee committee members and perceived opposition supporters, two of them women. One refugee said the Eritrean forces had informants in the camp: “We were so scared. We didn’t trust each other anymore, and we didn’t dare to speak among ourselves.”

The detained refugees were held at the camp for two days then taken away in Eritrean military vehicles. Their whereabouts remain unknown.

Killings, Rape, Detention, and Looting by Tigrayan Militias (Early December)

The Eritrean forces pulled out of Hitsats camp in early December, after heavy fighting around Edaga Hibret, south of Hitsats, a local resident reported. On December 5 at about 6 p.m., Tigrayan forces entered the camp and began shooting indiscriminately, injuring a woman, and sending hundreds of refugees fleeing.

During the conflict’s first months, the Tigrayan fighters were made up predominantly of the region’s special police forces, as well as local militia forces, which traditionally include retired soldiers. The extent of the special forces’ command and control over the militias in the initial months of the conflict was unclear. Later in the fighting, the Tigrayan forces self-branded as the Tigray Defense Forces (TDF).

Human Rights Watch spoke to eight refugees who fled north in the following days and were abused by Tigrayan militias in and around Zelasle and Ziban Gedena towns. Human Rights Watch was unable to confirm the number of refugees killed or injured in the incidents around Zelasle and Ziban Gedena, but interviews with witnesses suggest that at least two dozen people died between December 5 and 8.

Two refugees said that Tigrayan militia fighters and civilians armed with blunt weapons, including knives and machetes, encircled dozens of refugees at night, then threw a grenade at them. One survivor said: “They brought us toward an old riverbed with a hole where they would dig for gold. We were only held there for about 15 minutes before a grenade was thrown. We didn’t manage to flee far as we were encircled by people shooting.”

Several refugees said the militia fighters robbed them of the few possessions they carried. A 33-year-old man said 20 Tigrayan militiamen stopped him along with his cousin, his cousin’s pregnant wife, and their children: “they told us to go back to our camp. Then they stole everything we had with us. But we were alive, and so we were relieved.”

Two refugee women said that Tigrayan militia fighters raped them, along with four other women, when they escaped from the camp. A 27-year-old said that she and her 17-year-old sister were raped:

Two militia fighters caught us and told the boys with us to stop, but the boys fled. We were already so tired; we had no strength to run. They beat my sister and me. We fell to the ground; then they abused us. We lost consciousness after the rape. The men had disappeared when we came to [regained consciousness]. We found our clothes dispersed. We found a little hole in the ground, and we got into the hole, and it protected us a bit.

The militia fighters also detained scores of refugees in Zelasle town. A refugee who was detained for two days in what he thought was a school said a local administrator came:

He said, “We’ve helped a lot of Eritreans, and now we are suffering. Our villages are being burned by the Eritrean forces.” He said we would return to Hitsats, but anyone who collaborated with the Eritrean forces would face consequences. The problem was with the militiamen. Some wanted to kill us, while some wanted to follow his [the administrator’s] order.

While detained, the refugees received limited food and water. Two said they had to drink their urine because of the lack of water.

From Zelasle, the militia fighters marched hundreds of refugees back to Hitsats camp. The refugees, already suffering from hunger and thirst, said that the walk back, although just a few hours long, was grueling. Four of the refugees said they witnessed militiamen killing fellow refugees who became tired along the way. “One person, who I helped myself, he was very tired,” a 25-year-old refugee said. “But the militia fighter told me, ‘Leave him.’ And then they shot him. Some others, who didn’t think they would make it, gave us their ID cards to inform their families.”

Arbitrary Detention, Movement Restrictions, and Looting in Hitsats (December)

Once the refugees were back in Hitsats, Tigrayan special forces, Tigrayan militias, and members of the unidentified Eritrean opposition armed group, working together, detained hundreds of refugees in a warehouse previously run by a Dutch nongovernmental organization, ZOA, in a room in which charcoal was stored. Most were held for between three days and a week, some reportedly longer. A 25-year-old refugee said:

When I arrived, there were already 30 people there [in the warehouse]. In our group, we were 500. Little by little, they released people. First the women, then the elders. Those they kept longer were the younger people. For three days, I didn’t eat anything. When I was released, I spoke about the hunger, and so after that, refugees started to bring food to the detainees.

Tigrayan special forces, Tigrayan militias, and the Eritrean armed group brought Hitsats residents to the warehouse to identify refugees who had allegedly committed crimes. They also met with refugee elders, saying the refugees should return all looted goods.

For the rest of December, these forces, who were based in the host community and controlled the surrounding area, ordered the refugees not to leave the camp, telling them that they would be unable to protect them from further attacks if they left, refugees reported.

The refugees in the camp had very little food. A nurse in the camp said: “We would go and drink in a well that wasn’t clean. Then people started to eat moringa leaves. It was terrible. We lost three people, a young woman, an elderly woman, and a young man. They were hungry and ill, and they died.”

Tigrayan militias repeatedly came into the camp during this period and looted food and basic goods from the refugee community. A refugee leader said:

[The militia fighters] started to steal from us. We had no choice; they carried the guns. Three came to my home. They told me to give them all our blankets and mats. When we talked to their boss, we told him that they took all our blankets. The boss said if any militiamen came to you, come, and tell us. For at least two or three weeks they were stealing. But then it reduced.

No humanitarian aid reached the camp throughout this period.

In response to allegations that Tigrayan forces abused refugees, Getachew Reda, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) spokesman, told Human Rights Watch that special forces had not been present in Hitsats or Shimelba during this period. He said the TPLF could not account for the behavior of all allied militia and irregular forces.

Eritrean Forces Return and Burn, Destroy Hitsats Camp (early January)

On January 3, Tigrayan forces started to leave the Hitsats area as heavy fighting broke out in the vicinity. Three refugees and a Hitsats resident said that Eritrean forces fired mortars as they approached Hitsats from the northeast, with some rounds exploding within meters of the camp. They then took control of the camp and town.

Human Rights Watch analyzed satellite imagery recorded before, during, and after the attacks. Two burn scars on the ground are visible between January 2 and 4, over two hills, 100 and 600 meters north of Hitsats camp.

On January 4, Eritrean forces ordered the thousands of refugees remaining in the camp to leave and take the road toward Sheraro, a town near the Eritrean border. Desperate and terrified, refugees said they felt they had no choice.

One refugee who stayed in the vicinity of the camp until January 5 said he saw Eritrean forces spreading fuel in the camp and lighting it on fire: “The camp is no longer there, it’s burned down. It wasn’t just the camp; they also burned some homes of civilians [in the town].”

Satellite imagery and thermal anomaly data collected by an environmental sensor show that the destruction of the camp started on January 5 between 11:02 a.m. and 1:24 p.m. and continued for at least three days. On January 5 the fires seem to start around structures in the western part of the camp, within the camp’s residential zones. By January 6 at 11:03 a.m., humanitarian facilities in the eastern part of the camp, such as the International Rescue Committee (IRC) and Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) offices, were severely burned. Active fires, smoke plumes, and burn scars appear throughout the camp by January 8, reducing large swathes of the camp to ashes.

A UNHCR spokesperson said that when UNHCR reached the camps in late March, they found that “most of the shelters in an area known as Zone A, as well as UNHCR's offices and staff guesthouse, were burned to the ground.”

Trek to Eritrean Border, Coerced Repatriations (January)

Refugees who were forced to leave the camp in January described a harrowing days-long trek, with no provisions, as they walked toward Sheraro, which was then under Eritrean control. One refugee said:

The journey was terrible. There were fields that were burning, houses burning. A lot of sadness. We found abandoned donkeys and put elderly people on these donkeys. Some people were too tired, so people had to drop their clothes, suitcases. The Eritrean soldiers did not even help women who gave birth along the way but forced them to keep walking.

The refugee said he saw one woman, who reportedly suffered from diabetes, die along the way.

Once they reached Sheraro and the contested town of Badme, some refugees felt they had no choice but to continue into Eritrea.

A 20-year-old refugee who returned to Eritrea via Badme said the Eritrean forces took three weeks to process those waiting to return to Eritrea around Badme, even though the refugees there had little food or shelter. She and hundreds of others eventually boarded buses and headed to Eritrea. While UNHCR said they were unable to verify the number of refugees that may have returned to Eritrea, ARRA said that they believed all those who ended up at the border returned to Ethiopia.

Abuses in Shimelba Camp by Eritrean Forces

Human Rights Watch interviewed five Eritrean refugees who fled Shimelba camp and faced violence and abuses, primarily from Eritrean forces, and spoke with aid workers who interviewed survivors from Shimelba.

Eritrean forces occupied Shimelba camp on November 17. Refugees said the Eritrean forces immediately threatened and intimidated them, pressuring them to leave. The soldiers called a meeting and told the refugees that “UNHCR would not be coming for them” and ordered them to return to Eritrea.

Eritrean soldiers walked around the camp with lists and detained approximately 20 refugees, men, and some women, including several community leaders. The refugees were taken away to an unknown location.

On December 7, as they occupied the camp, Eritrean forces executed six or seven Tigrayans in the vicinity of the camp, and left their bodies largely uncovered, sparking fear among the refugees. Many refugees fled Shimelba to the town of Sheraro, approximately 35 kilometers away. The Eritrean forces exerted considerable pressure on the refugees in Sheraro to return to Eritrea, the refugees said. One said: “Eritrean forces came into a big hall where we sheltered and told us that we had to leave. Some they took by force. In the street, if they found us, they told us to leave.”

Hundreds of refugees eventually returned to Shimelba. Meanwhile, Tigrayan militia fighters and special forces occupied Shimelba camp and prohibited refugees who remained from leaving.

Eritrean forces returned to Shimelba on December 16. Aid workers who spoke with survivors said that Eritrean soldiers shot dead at least one refugee at his home in front of his family and raped at least four refugees in the camp and its vicinity.

Around December 17, heavy fighting took place in and around the camp. Eritrean forces again took control of the camp.

Three residents said that at least six refugees were killed during the fighting. One witness said: “The heavy bombs were falling in the DICAC [Development and Inter-Church Aid Commission] schoolyard, and behind the schoolyard, there were local residents’ houses. Some of the civilian houses were destroyed. The schoolyard was in flames.” Satellite imagery recorded on December 17 at 10:42 a.m. shows burned ground in the DICAC schoolyard that then expanded across the schoolyard on December 18.

Satellite imagery collected on December 16, 17 and 18 show the progressive expansion of burn scars in Shimelba refugee camp, specifically in the DICAC [Development and Inter-Church Aid Commission] schoolyard, located on the eastern side of the image. Satellite imagery © Planet Labs Inc

Hardships Facing Eritrean Refugees Remaining in Ethiopia

For refugees who found a way to remain in Ethiopia, survival has been hard.

In December the deputy head of ARRA told the media that the government was returning hundreds of refugees who had fled from Tigray to Addis Ababa back to the two functioning refugee camps, Mai Aini and Adi Harush. In January UNHCR raised concerns about refugees being returned against their will after ARRA informed them that 580 Eritreans had been taken back to Tigray. In its September 10 response letter, ARRA said that refugees arriving in Addis Ababa from Tigray had created logistical complications and that the refugees were returned after an ARRA assessment team found the two southern camps to be safe.

Most of the refugees identified had moved to or been moved to Mai Aini, Adi Harush, and Addis Ababa. UNHCR told Human Rights Watch that as of late August, of the refugees who are known to have received food rations in Hitsats and Shimelba in October 2020, 12,611 have been identified, while 7,643 remain unaccounted for. ARRA, however, said that the great majority of refugees from Hitsats and Shimelba have been accounted for, but the agency acknowledged that refugees could have been counted twice.

Human Rights Watch found that refugees outside of camps lacked access to urgent assistance. For several months, those who had made their way to Shire, a town in central Tigray, received no food assistance other than some high-energy biscuits. All the refugees interviewed by Human Rights Watch who had fled to Addis Ababa said that they needed urgent assistance, including medical care, food, and shelter.

In May, UNHCR said that many refugees needed urgent assistance, but that discussions with the government were ongoing about providing this assistance outside the camp setting. In August UNHCR reported that ARRA had agreed to provide refugees who had arrived in Addis Ababa from Hitsats and Shimelba with temporary identification documents for three years, which would enable them to open bank accounts and receive support through cash transfers. ARRA confirmed this to Human Rights Watch. At the time of writing, refugees in Addis Ababa had still not received this support.

Refugees in Adi Harush and Mai Aini, along with UNHCR, raised concerns about armed men engaged in crime in both camps. In February, for instance, unidentified armed men attacked three refugees as they lined up for scarce water at about 5 a.m., wounding one and stealing their belongings.

On July 12, fighting broke out in and around Mai Aini and Adi Harush between the Tigrayan Defense Forces and Amhara regional forces, killing at least one refugee, according to UNHCR. The insecurity in the area caused access to aid, including food and water, to be cut off. UNHCR said that emergency assistance started again on August 5 but warned that “basic services such as health care remain unavailable, and clean drinking water is running out.” ARRA said on September 10 that, given the insecurity, they currently do not have a presence in the camps. While Tigrayan forces reportedly control the camps and vicinities, reports of insecurity and clashes in the area persist. Responding to a query about plans to relocate Eritrean refugees out of Tigray, Getachew Reda, the TPLF spokesman, questioned whether there were any credible security concerns for Eritrean refugees remaining in Tigray.

International Legal Obligations

Eritrean refugees in Ethiopia are protected by international human rights and humanitarian law. International humanitarian law, or the laws of war, prohibits attacks against civilians, including refugees, and civilian property, and requires parties to the conflict to facilitate humanitarian access to civilians in need. The warring parties who have committed abuses against refugees are responsible for laws-of-war violations. Individuals who have committed serious violations with criminal intent can be held responsible for war crimes.

Ethiopia is a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol and to African regional refugee conventions. These hold Ethiopia responsible for ensuring the protection of refugees within its territory and for cooperating with the UN refugee agency to facilitate its response to refugee crises.

UNHCR’s Executive Committee has long condemned military or armed attacks on refugee camps, and has said that governments should preserve the civilian and humanitarian character of refugee camps, ensure safe access for humanitarian assistance, and hold accountable those responsible for attacks on the security of refugees.

Recommendations

- All parties to Ethiopia’s armed conflict should immediately cease attacks and abuses against Eritrean refugees and other civilians. They should respect the humanitarian nature of refugee camps and not deploy forces there. They should facilitate humanitarian access and freedom of movement for all refugees;

- The Ethiopian government should, with international support, provide immediate and adequate emergency assistance, including medical care, food, and shelter, to the thousands of refugees and asylum seekers currently displaced outside of camps, including in Sheraro, Adigrat, and Addis Ababa. They should identify and support those at particular risk or with specific needs, including women, the high caseload of unaccompanied and separated minors and other children, older people, and people with disabilities;

- The government should also ensure the physical safety of refugees within its territory, including by: protecting Eritrean refugees from Eritrean and other armed forces and groups; ensuring humanitarian access to all refugee camps and conflict areas; and committing to not forcibly returning Eritrean refugees to Eritrea or to areas where their lives and security would be at risk;

- Any UN-led, international investigation into alleged international crimes in the Tigray region should include an investigation into warring parties’ actions against Eritrean refugees and protected humanitarian infrastructure;

- Tigrayan armed forces should ensure the protection of Eritrean refugees in areas under their control, including through ensuring humanitarian access to all refugee camps, freedom of movement for all refugees, and cooperating with international investigations into abuses against Eritrean refugees;

- Ethiopia, Eritrea, and UNHCR should cooperate to account for the whereabouts and well-being of the thousands of refugees from Hitsats and Shimelba camps and throughout Tigray still unaccounted for; and

- UNHCR and affected governments should accelerate the handling of pending cases of third-country resettlement for Eritrean refugees in Ethiopia, as a highly vulnerable group.