STATEMENT OF INTEREST

Immigrant Legal Resource Center (“ILRC”), Human Rights Watch, and Freedom For Immigrants (“FFI,” formerly Community Initiatives for Visiting Immigrants in Confinement) (collectively, “Amici”) respectfully submit this brief in support of Defendants.[1]

ILRC is a national nonprofit legal support center with offices in California, Texas, and Washington D.C. The mission of the ILRC is to work with, educate, and enhance the capacity of immigrants, community organizations, and the legal sector in order to build a democratic society that values diversity, dignity, and the rights of all people. Founded in 1979, the ILRC is regarded as one of the foremost experts on engaging immigrants and developing their leadership in the democratic process, providing expertise on complex issues of immigration law, procedure and policy, and engaging in advocacy and educational initiatives on policies that affect immigrants.

Human Rights Watch is a non-profit, independent organization and the largest international human rights organization based in the United States. Since 1978, Human Rights Watch has investigated and exposed human rights violations and challenged governments to protect the human rights of citizens and noncitizens alike. Human Rights Watch investigates allegations of human rights violations in more than 90 countries around the world, including in the United States, by interviewing witnesses, gathering information from various sources, and issuing detailed reports. Where human rights violations have been found, Human Rights Watch advocates for the enforcement of those rights with governments and international organizations and in the court of public opinion.

FFI (formerly Community Initiatives for Visiting Immigrants in Confinement) was founded in 2010 as the first immigration detention visitation program in California. It then joined forces with four other visitation programs around the country and established a national visitation network. Between 2012 and the present, FFI helped to grow a national visitation network and launched the largest national free hotline for people in immigration detention. FFI’s affiliated vistitation network visits and monitors 69 immigrant prisons and jails in California and nationwide. Through these visits, FFI gathers data and stories to combat injustice at the individual level and push for systematic change.

Amici believe that the Court in this matter would benefit from our organizations’ experiences working on the ground with people held in privately run immigration detention facilities. Amici respectfully submit that such experience helps elucidate the current threat to the health, safety, and welfare of these populations.

ARGUMENT

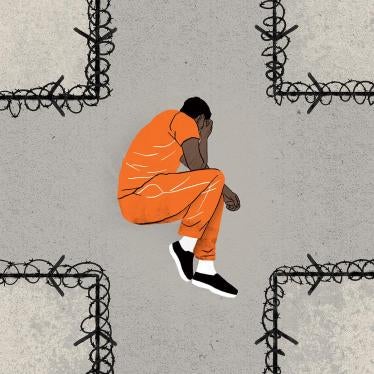

At present, four out of the seven immigration detention centers in California are privately run facilities. These four hold an average of nearly 3,600 people on a given day, or approximately 95% of the total immigration detainee population in California.[2] These privately run detention facilities hold various populations including asylum seekers and long-term residents of California, many of whom are parents of U.S. citizens,[3] sometimes for days, sometimes for months or years. Many people are held without individualized bond hearings, lacking the ability to even ask a judge whether they may fight their case out of detention.

Those detained in California-based privately run immigration detention centers are exposed to a host of inhumane conditions, from serious, sometimes deadly, lack of adequate medical care to sexual abuse to everyday indignities. The true extent of inhumane conditions in privately run immigration detention centers in California is impossible to determine without full access to these centers, but even the limited anecdotal evidence that is available to Amici is horrific. One person bled to death after an attempt to remove “the largest abdominal mass” a doctor had ever seen, which went undetected by detention center staff even though the detained person constantly complained of pain and requested treatment over the course of two years. Another person suffered a miscarriage when she fell on her stomach while shackled at her hands and feet, and then was denied the necessary medical and mental health follow-up care. Detained persons suffer serious mental health conditions and yet do not have access to mental health professionals or are placed in solitary confinement. Since 2017, 11 of 35 ICE in-custody deaths have been apparent suicides.[4]

Particularly vulnerable populations such as women and LGBTQ individuals are subject to unique degradation and sex abuse. Instead of finding refuge, torture victims who fled to the United States precisely because they were seeking asylum from persecution elsewhere are locked away in abusive and dangerous detention centers.[5] Detained persons have even gone on hunger strikes for something as basic as new underwear.

This brief offers examples of the conditions of privately run immigration detention centers in California based on stories learned by Amici through their interactions with detained persons. Amici seek to underscore the vital importance of the State of California using its police powers to protect the health, safety, and welfare of the extremely vulnerable population stuck inside the privately run immigration detention facilities.

California’s privately run immigration detention centers are currently not compatible with the fundamental rights of its residents and the concept of basic human dignity. The State has decided that the risks to the health, safety, and welfare of its residents in these facilities is simply too great to allow them to continue in operation. Amici urge the Court to consider the significant evidence that the health, safety, and welfare of immigration detainees is at serious risk in these facilities in deciding the various pending motions before the Court.

- THE HEALTH, SAFETY, AND WELFARE OF DETAINEES ARE AT SIGNIFICANT RISK IN PRIVATELY RUN IMMIGRATION DETENTION FACILITIES.

Evidence available to Amici indicate systemic issues with the general welfare, health, and safety of those detained in California’s immigration detention centers. California has the “general authority to ensure the health and welfare of inmates and detainees in facilities within its borders . . . .” United States v. California, 921 F.3d 865, 886 (9th Cir. 2019)

. As the accounts below illustrate, there is an urgent need to address widespread risk to detainees in these privately run facilities.

One of the top complaints by immigration detainees in California is lack of access to adequate medical care.[6] In the individual accounts presented below, individuals suffered because of unreasonable delay in receiving care, treatment by unqualified staff, and inappropriate treatment and care. Amici believe that many more such cases exist, indicating substandard medical care in privately run immigration detention centers in California. Systemic failure to provide adequate medical care is likely given that many staff providing medical care at these immigration detention centers are unqualified to conduct complicated medical assessments.[7] In some cases, medical staff may even ignore their duty of care entirely.[8]

Raul Ernesto Morales-Ramos, a 44-year old man, died in April 2015 while detained in the Adelanto Detention Facility, run by GEO Group, from organ failure and suffering widespread signs of cancer.[9] Despite the fact that he had complained of pain and exhibited cancer symptoms over the course of two years, and had a large, clearly visible abdominal mass, Mr. Morales-Ramos did not receive adequate medical care until just a month before he died. His death resulted from a critical lapse of care: had he been diagnosed and treated sooner, Mr. Morales-Ramos’ cancer was treatable.[10]

Likely already suffering from symptoms of cancer, Mr. Morales-Ramos was first referred for follow-up with a doctor for gastrointestinal symptoms in April 2013 while detained at the Theo Lacy Facility in Orange County, California. More than a year later, in May 2014, this consultation had not yet occurred, and Mr. Morales-Ramos was transferred to Adelanto with no documentation of his gastrointestinal symptoms. There, he was seen by registered nurses several times over the next nine months after submitting sick call requests for body aches, weight loss, pain in his joints, knees, and back, and diarrhea. No one thought to diagnose or treat him for cancer.

In February 2015, having suffered for a year without proper treatment, Mr. Morales-Ramos submitted a grievance in which he pled, “To who receives this. I am letting you know that I am very sick and they don’t want to care for me. The nurse only gave me ibuprofen and that only alleviates me for a few hours. Let me know if you can help me. I only need medical attention.” Four days later, a nurse practitioner saw Mr. Morales-Ramos but missed all symptoms of cancer, instead instructing him to increase his water intake and exercise and documenting that his symptoms were resolved. A few weeks later, on March 2, 2015, another nurse saw Mr. Morales-Ramos and noted a distended abdomen but “did not detect a mass or protrusion.”

A consultation with a doctor finally occurred on March 6, 2015. This doctor—observing Mr. Morales-Ramos just four days after a nurse failed to detect a mass—documented the “largest [abdominal mass] she had ever seen in her practice,” which was “notably visible through the abdominal wall.” She scheduled Mr. Morales-Ramos for a colonoscopy, which did not occur until about one month later. During the colonoscopy, Mr. Morales-Ramos began to experience abdominal bleeding after a doctor attempted to remove the mass. Mr. Morales-Ramos was transferred to the hospital and died three days later after a surgical attempt to stop his bleeding.[11]

Monserrat Ruiz Cuevas suffered a miscarriage while detained at Mesa Verde Detention Center in Bakersfield, which is run by Geo Group.[12] After her miscarriage, Ms. Ruiz said that she was further denied access to adequate follow-up medical and mental health care.

When Ms. Ruiz first arrived at Mesa Verde on May 8, 2015, after seeking asylum based on a credible fear of persecution or torture, staff conducted a pregnancy test. However, Ms. Ruiz said that she was not informed of the result. Instead, Ms. Ruiz only learned she was pregnant several days later after she experienced heart and breathing complications, was transported to a hospital for urgent care (while fully shackled), and examined by a doctor who informed her she was pregnant and had severe dehydration.

After her pregnancy was confirmed, Ms. Ruiz said she was still not provided with access to specialized medical care. On May 12, 2015, she complained of back pain and other distressing symptoms but had to wait two days until staff determined she should be sent to a hospital. On May 14, 2015, while walking to the transportation van to go to the hospital, Ms. Ruiz was shackled in both leg and arm restraints. She tripped over her shackles and fell on her stomach while being transported to a hospital to receive urgent medical care related to her pregnancy. Once at the hospital, Ms. Ruiz said she was kept in shackles the entire time and the doctor did not take any steps to address her concerns about harming her baby because of the fall.

The following day, on May 15, 2015, Ms. Ruiz began bleeding heavily and experiencing other symptoms of miscarriage. She said she was transported to the hospital in handcuffs, waited several hours to see the doctor while handcuffed to the stretcher, and then transferred to the hospital bed and handcuffed to the bed. After she was evaluated, the doctor told Ms. Ruiz that she had lost her child. Ms. Ruiz said she was then transported back to Mesa Verde that same day, once again in handcuffs.

After her miscarriage, Ms. Ruiz said that she did not receive any necessary follow-up gynecological care or mental health services. Despite the fact that she continued to experience ongoing bleeding and vaginal irritation, she said there were no efforts to ensure that she had not contracted an infection or that her hemorrhaging had ceased. Even after Mesa Verde medical staff determined that she needed urgent care from a gynecologist, Ms. Ruiz was never provided with this care, she said. Instead, she only received Tylenol and milk of magnesia.

Ms. Ruiz also said that she did not receive any mental health care (further discussed in section II.B.i, below) although she was visibly weeping and depressed for several days. Ms. Ruiz said she was eventually taken to see a psychiatrist who chuckled and said that all he could do for her was prescribe sleeping medication. Ms. Ruiz was subsequently granted asylum and released to live with her partner, a legal permanent resident.

Jose L. lost the ability to walk more than just short distances, and perhaps also lost sight in his right eye, due to failure to receive adequate medical care while detained at Geo Group’s Adelanto Detention Facility.[13] Jose, a 54-year-old former green card holder who had lived in the U.S. for 32 years, had a history of lower back pain and diabetes. In mid-2013, Jose was working in the facility kitchen when he slipped and fell, hitting his hip and back. After his pain became uncontrollable and he could not stand up for more than five minutes, Jose asked to see a doctor but had to wait 18 months before seeing a surgeon. This unreasonable delay left Jose in pain and with decreased function. Jose was eventually scheduled for surgery but was deported before he could have the surgery.

Unreasonable delays in receiving care may have also resulted in Jose becoming legally blind in his right eye. In July 2014, Jose began to complain about losing vision in his right eye and severe pain, which was eventually diagnosed as proliferative diabetic retinopathy, a common complication of diabetes. From the time he first complained, it took five days for Jose to receive an initial evaluation by a physician, who thought he might have a retinal detachment, which according to medical experts should have been deemed an emergency. Forty-eight hours later, the optometrist found Jose’s eye had hemorrhaged and recommended that he see a retinal specialist as soon as possible. It then took the facility doctor four days to submit a request for authorization stating, “needs retinal specialist ASAP,” and over a month before Jose was seen by a retinal specialist. Afterward, numerous recommendations for follow-up appointments with a retinal specialist were delayed. For example, a follow-up scheduled for one week later occurred four weeks later. At one point, the retinal specialist cancelled the appointment due to non-payment, presumably by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (“ICE”).

Because proliferative diabetic retinopathy does not develop overnight, symptoms should have been observed during Jose’s annual eye exam in February 2014. Jose’s diabetes does not appear to have been managed well overall, and although his sugar level was high, the doctors did not make changes to his insulin dosages.

- Vulnerable populations face particular challenges.

Many immigration detainees are survivors of violence and torture. These detainees are unusually vulnerable and may often fall victim to additional harms while in detention, a particularly ironic circumstance given that they have often entered the country seeking, as intended by federal policy, asylum from persecution in their home countries. This is sadly reflected in the fact that there is a high number of attempted and completed suicides at immigration detention centers.[14] “I think doing something like that is something that has crossed the mind of all of us who are locked up here,” a detainee at Geo Group’s Adelanto said of suicide.[15]

The high rate of suicide at California’s privately run immigration detention centers must be understood within the context of a system that has a track record of failure to treat mental health issues and suicide risk.

First, suicide risks are not addressed. At Adelanto, the Office of Inspector General (OIG) reported in September 2018 “the recurring problem of detainees hanging bedsheet nooses at the Adelanto Center.”[16] During an inspection, the OIG observed braided bedsheets hanging in 15 out of the approximately 20 male detainee cells visited.[17] Despite their potential to assist in suicide, ICE did not remove the hanging bedsheets as it was “not a high priority” according to “two contract guards.”[18] Due to Adelanto’s inadequate approach to placing potentially suicidal detainees in punitive suicide watch cells without any mental health treatment, detainees may fail to disclose suicidality.[19] This, combined with the lackadaisical approach to removing suicide threats, creates an unnecessarily dangerous environment.

Second, private immigration detention centers attempt to treat detained persons suffering from mental health problems by putting them in solitary confinement instead of providing individualized treatment.[20] Two attorneys of clients with mental health conditions detained in Adelanto Detention Center told Human Rights Watch their clients were regularly put into isolation because adequate mental health care was unavailable.[21] In one particular case, a detained person had done well in a psychiatric facility, but when she was returned to Adelanto, she did not receive the same medication she had received in the hospital. She became unstable and suicidal and was repeatedly put in isolation.[22] Another attorney working with detained persons stated, “I’ve had clients, very mentally ill clients . . . who’ve suffered from schizophrenia and various psychotic episodes, and the way [detention center operators] responds to that is to put people in solitary.”[23] At one point, eight percent of people in immigration detention interviewed by FFI at Adelanto reported that they had been held in solitary confinement.[24]

Studies suggest that solitary confinement may severely exacerbate previously existing mental health issues. Because of this, the United Nations special rapporteur on torture has stated that solitary confinement of any duration of time for those with psychosocial disabilities is cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment.[25] The Special Rapporteur cites to studies that have found that spending seven days in solitary confinement can lead to a decline in brain activity, and that over seven days, the decline may be irreversible.[26] According to a recent OIG report, the Adelanto facility compounds the innate risks of solitary confinement to all persons by a failure to follow rules regarding recreation, basic hygiene practices, and unnecessary restraints.[27]

- ii. Other vulnerable populations face serious risks in private immigration detention facilities.

In addition to the lack of mental health care and issues faced by the general population of detained persons, certain groups of unusually vulnerable detained persons such as women and LGTBQ individuals suffer additional problems in private detention facilities.

Because there are fewer women than men in these facilities, their particular needs are often overlooked. They are often consolidated, with lower security risk women housed along with higher security risk women, resulting in more constrictive conditions for all women than their male counterparts.

Sexual and physical abuse is a serious problem in California’s immigration detention centers, and certain populations such as LGBTQ detained persons face higher risks of abuse. Data obtained by FFI from the Department of Homeland Security Office of the Inspector General shows at least 1,016 reports of physical and sexual abuse filed by people in detention nationwide between May 2014 and July 2016.[28] Two privately run California facilities—Geo Group’s Adelanto and CoreCivic’s Otay Mesa Detention Center—are among the five facilities with the most sexual assault complaints in the nation.[29] At Otay, Yordy Cancino, a gay man, reported that he experienced consistent sexual harassment by guards.[30] Mr. Cancino said that when he took showers, one of the male guards would position himself so that he could see Mr. Cancino naked and guards would call him over the detention facility radio, “Cancino, my royal princess, wake up.”[31]

LGBTQ detained persons are fifteen times more likely than the general population of detained persons to be sexually assaulted in detention centers.[32] Detained transgender women often suffer abuse because they are housed with men or in prolonged isolation.[33] These conditions create particular and unreasonable mental and physical health risks for an already vulnerable population. The documented high risk of sexual assault in Otay and Adelanto underlines the uniquely critical needs to protect transgender women in these facilities.

The harmful, abusive, and even life-endangering conditions of confinement described above are exacerbated by the fact that most detained persons have no access to counsel. An estimated 68% of immigration detainees in California are unrepresented by counsel.[34] Studies at Adelanto suggest that as few as 12.3% of detainees are represented.[35] In that facility as in other private facilities, access to counsel is restricted due to several factors including costly telephone access, limited visitation, and frequent and distant transfers. Telephone calls are extremely expensive for detainees. Prior to 2013, calls could be as exorbitant as $5.00 per minute. Since then, the FCC set interstate caps for rates charged to detainees, but rates can still be as high as 25 cents per minute. Visitation is also unreasonably restricted. In January 2017, FFI filed a complaint against Geo Group’s Adelanto, documenting visit denials and unreasonable visitation waiting times.[36] Also in 2017, over 60 faith leaders and attorneys were denied visits to Adelanto without being provided any reason.[37] On top of this, current restrictions make it difficult if not impossible to bring interpreters to detention centers, limiting the ability of legal workers to communicate with detainees.

The evidence available to Amici from their sources suggest a picture of dire general welfare, health, and safety conditions in immigrant detention centers in California. Amici respectfully urge the Court to weigh the urgency of these considerations and the State of California’s strong interest in protecting the health, safety, and welfare of immigrants and detainees in private immigration detention centers within its borders as it considers the parties’ motions.

Dated: March 12, 2020 Respectfully submitted,

By: s/ Eric R. Havian

ERIC R. HAVIAN

ehavian@constantinecannon.com

SARAH P. ALEXANDER

spalexander@constantinecannon.com

CONSTANTINE CANNON LLP

150 California Street, Suite 1600

San Francisco, CA 94111

Telephone: (415) 639-4001

Facsimile: (415) 639-4002

Attorney for Amici Curiae

Immigrant Legal Resource Center,

Human Rights Watch

& Freedom for Immigrant

[1] Counsel for all parties have consented to the filing of this brief. No counsel for a party authored this brief in whole or in part, and no such counsel or party made a monetary contribution intended to fund the preparation or submission of this brief. No persons other than the amici or their counsel made a monetary contribution to this brief’s preparation or submission.

[2] “I Still Need You”: The Detention and Deportation of Californian Parents, Human Rights Watch (May 15, 2017), https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/05/15/i-still-need-you/detention-and-deportation-californian-parents; see also Detention by the Numbers, Freedom For Immigrants, https://www.freedomforimmigrants.org/detention-statistics/.

[3] Supra fn. 2.

[4] Deaths at Adult Detention Centers (AILA Doc. No. 16050900), American Immigration Lawyers Association (updated March 9, 2020), https://www.aila.org/infonet/deaths-at-adult-detention-centers.

[5] In 2014, 84% of asylum seekers who suffer a positive credible fear of persecution in their home countries were detained. Olga Byrne, Eleanor Acer & Robyn Barnard, Lifeline on Lockdown: Increased US Detention of Asylum Seekers, Human Rights First (July 2016), http://www.humanrightsfirst.org/sites/default/files/Lifeline-on-Lockdown.pdf.

[6] Top Complaints in California Immigration Detention Facilities, Community Initiatives for Visiting Immigrants in Confinement (“CIVIC”) (Aug. 28, 2015), http://www.endisolation.org/blog/archives/1278.

[7] U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s Office of Detention Oversight itself noted that in Adelanto, for instance, “approximately 50 percent of ADF’s medical staff hires are new graduates” with a “definite difference between their skills and those of more experienced nurses.” Clara Long & Grace Meng, Systemic Indifference: Dangerous & Substandard Medical Care in US Immigration Detention, Human Rights Watch (May 8, 2017), https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/05/08/systemic-indifference/dangerous-substandard-medical-care-us-immigration-detention.

[8] Office of Inspector General, Management Alert—Issues Requiring Action at the Adelanto ICE Processing Center in Adelanto, California, OIG-18-86 (September 27, 2018) (during its inspection of Adelanto, the OIG “observed two doctors walking through disciplinary segregation and stamping their name on the detainee records, which hang outside each detainee’s cell, indicating that they visited with the detainee. However, we observed them doing so without having any contact with 10 of the 14 detainees in disciplinary segregation”).

[9] All facts in this story are from Human Rights Watch’s review of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement records detailed in Systemic Indifference: Dangerous & Substandard Medical Care in US Immigration Detention. See supra fn. 7.

[10] One medical reviewer who examined the case found that “Had Mr. Morales’ gastrointestinal symptoms been evaluated much sooner as was clinically indicated, it is possible that the malignancy from which Mr. Morales died, might have been caught at a time when it was still treatable.” Supra fn. 7.

[11] A recent OIG report on Adelanto and three other facilities called out the “poor condition” of the physical plant, “including mold and peeling paint on walls, floors, and showers, and unusable toilets” in the bathrooms, which creates “health issues for detainees, including allergic reactions and persistent illnesses.” Office of Inspector General, Concerns about ICE Detainee Treatment and Care at Four Detention Facilities, at 8, OIG-19-47 (June 3, 2019), https://www.oig.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/assets/2019-06/OIG-19-47-Jun19.pdf. These concerning physical-plant conditions compound the risks presented by inadequate and inattentive medical care by medical staff. That same report found “egregious” violations of basic food safety practices at Adelanto, including “lunch meat and cheese were mixed and stored uncovered in large walk-in refrigerators; lunch meat was also unwrapped and unlabeled; chicken smelled foul and appeared to be spoiled; and food in the freezer was expired.” Id. at 4. Such neglect to basic food safety puts the health of all detainees at risk.

[12] Letter to Timothy S. Aitken, Field Office Director, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement re: Violations of Policy Regarding Detention, Shackling, and Care of Pregnant Women at Mesa Verde Detention Facility, American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California (June 18, 2015), https://www.aclusocal.org/sites/default/files/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Mesa-Verde-Ruiz-Letter-FINAL.pdf.

[13] All facts in this story are from Human Rights Watch’s review of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement records detailed in Systemic Indifference: Dangerous & Substandard Medical Care in US Immigration Detention. See supra fn. 7.

[14] Paloma Esquivel, “We don’t feel okay here”: Detainee Deaths, Suicide Attempts, and Hunger Strikes Plague California Immigration Facility, Los Angeles Times (Aug. 8, 2017), http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-adelanto-detention-20170808-story.html; see also supra fn. 8 (stating that from December 2016 to December 2017, there were reports of at least seven suicide attempts at Adelanto, and that 4 of the 20 detainee deaths repoted nationwide between October 2016 to July 10, 2018 were the result of self-inflicted strangulation).

[15] Supra fn. 14.

[16] Supra fn. 8.

[17] Id.

[18] Id.

[19] There Is No Safety Here: The Dangers for People with Mental Illness and Other Disabilities in Immigration Detention at GEO Group’s Adelanto ICE Processing Center, at 13, Disability Rights California (Mar. 5, 2019), https://www.disabilityrightsca.org/post/there-is-no-safety-here-the-dangers-for-people-with-mental-illness-and-other-disabilities-at.

[20] Id. at 20 (noting “Review of detainee records confirm the lack of individualized care. For example, clinical staff repeatedly recommend “breathing techniques and physical exercise,” even for detainees in highly restrictive units with extremely limited out-of-cell recreation time, and thus almost no opportunity to engage in “physical exercise.”).

[21] Supra fn. 7; see also supra fn. 19.

[22] Supra fn. 7.

[23] Alexis Perlmutter & Mike Corradini, Invisible in Isolation: The Use of Segregation and Solitary Confinement in Immigration Detention, National Immigrant Justice Center and Physicians for Human Rights (Sept. 2012) https://www.immigrantjustice.org/sites/immigrantjustice.org/files/Invisible%20in%20Isolation-The%20Use%20of%20Segregation%20and%20Solitary%20Confinement%20in%20Immigration%20Detention.September%202012_7.pdf.

[24] Christina Fialho & Victoria Mena, Abuse in Adelanto: An Investigation into a California Town’s Immigration Jail, CIVIC and Detention Watch Network (October 2015), https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5a33042eb078691c386e7bce/t/5a9dad7be4966b064c98e07c/1520283004817/CIVIC_DWN-Adelanto-Report_old.pdf.

[25] Juan Ernesto Mendez (Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment), Torture And Other Cruel, Inhuman Or Degrading Treatment Or Punishment, U.N. Doc. A/66/268 (Aug. 5, 2011), https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N11/445/70/PDF/N1144570.pdf?OpenElement (“Mendez Statement”); see also Jamie Fellner, Callous and Cruel: Use of Force against Inmates with Mental Disabilities in US Jails and Prisons, Human Rights Watch (May 12, 2015), https://www.hrw.org/report/2015/05/12/callous-and-cruel/use-force-against-inmates-mental-disabilities-us-jails-and; Maureen L.O’Keefe, et al., One Year Longitudinal Study of the Psychological Effects of Administrative Segregation, National Institute of Justice (Oct. 31, 2010), https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/232973.pdf.

[26] Mendez Statement, supra fn. 25, at 1 (citing Stuart Grassian, Psychiatric Effects of Solitary Confinement (1993)).

[27] Supra fn. 11, at 5–6.

[28] Letter to Thomas D. Homan, Director, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, et al., CIVIC (April 11, 2017), https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5a33042eb078691c386e7bce/t/5a9da297419202ab8be09c92/1520280217559/SexualAssault_Complaint.pdf.

[29] Id.

[30] Complaint to the Office for Civil Rights & Civil Liberties within the Department of Homeland Security, Freedom For Immigrants (April 11. 2017), https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5a33042eb078691c386e7bce/t/5a9da297419202ab8be09c92/1520280217559/SexualAssault_Complaint.pdf (“FFI Complaint”); see also Mari Payton, Advocacy Group: If You’re Abused in Immigration Detention, the Government Doesn’t Care, NBC San Diego (April 27, 2017, updated on April 28, 2017), https://www.nbcsandiego.com/news/local/Advocacy-Group-If-Youre-Abused-in-Immigration-Detention-the-Government-Doesnt-Care-420666314.html.

[31] FFI Complaint, supra fn. 30.

[32] A Call for Change: Protecting the Rights of LGBTQ Detainees, Just Detention International (Feb. 2009), https://justdetention.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Call-for-Change-Protecting-the-Rights-of-LGBTQ-Detainees.pdf.

[33] See US: Transgender Women Abused in Immigration Detention, Human Rights Watch (March 23, 2016), https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/03/23/us-transgender-women-abused-immigration-detention.

[34] California’s Due Process Crisis: Access to Legal Counsel for Detained Immigrants, The California Coalition for Universal Representation (June 2016), http://www.publiccounsel.org/tools/assets/files/0783.pdf.

[35] Supra fn. 24.

[36] CIVIC Files Civil Rights Complaint Alleging Frequent Denial of Visits at Adelanto Since Trump’s Election, CIVIC (Jan. 18, 2017), http://www.endisolation.org/blog/archives/1170.

[37] ICE Violates First Amendment Rights of 60+ Attorneys and Faith Leaders, CIVIC (June 27, 2017), http://www.endisolation.org/blog/archives/1265.