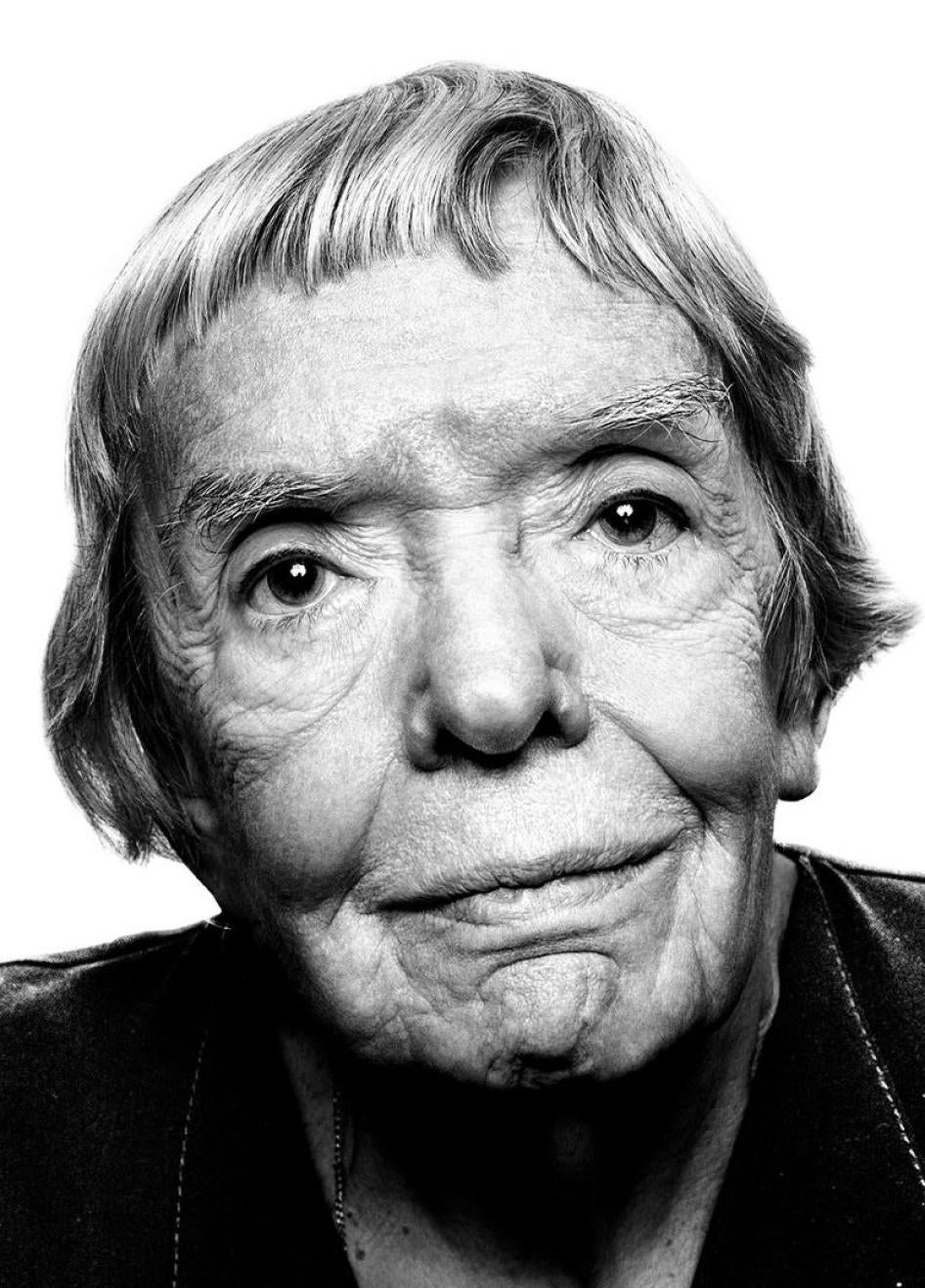

My favorite photo of Lyudmila was taken in 1973. Lyuda with a group of friends, sitting on a couch, arms around each other, joyful in their camaraderie. A few years later, in 1976, they would form the Moscow Helsinki Group to report on violations of human rights in their country. In doing so, they became victims themselves. Within a short time, most of their members were gone, sentenced to prison or labor camp, followed by internal exile. In 1977, Lyuda was forced into exile; she settled in the United States, where she became the group's official representative abroad.

I first saw Lyuda at a demonstration outside the Soviet Consulate in New York. I was protesting as part of an Amnesty International group. Lyuda was busy organizing a group of Soviet dissidents. I was struck by her energy. She seemed to be everywhere, distributing placards, lining up groups, always cheerful and smiling. I was also struck by her mismatched clothes, right down to her socks. Clearly this dedicated woman had dressed that morning with more than appearance on her mind.

When Helsinki Watch began work in 1979, someone suggested we hire Lyuda as a part-time consultant. Lyuda's English at that time was as rudimentary as my Russian, so a proper interview was not really possible. Like much of what we did in those early days, I hired her on instinct and faith.

Our office was small, the initial staff even smaller. Helen Senn, our first Russian-speaking researcher, sat in an office adjoining mine. I could hear her on the phone, talking with Lyuda on a daily basis. Their conversations were punctuated by gales of laughter and whispered confidences that inferred choice pieces of gossip, hardly what one would expect from a consultant whose friends and colleagues back home were being arrested and tortured by the authorities.

It took me a while to understand what every good human rights worker comes to know, that by personalizing the victims of oppression, one learns to care for them as real people, not just as names on an ever-growing list of prisoners. Lyuda's tales of her colleagues at home, their families, their beliefs, their foibles, even their indiscretions, brought them to life to those of us who would spend the next 10 years working for their freedom.

Lyuda became a regular presence in our offices. She was funny and gregarious. Her high spirits and captivating warmth belied the heavy cause to which she was dedicated. A hug from Lyuda often made my day. I once asked her whether she had been afraid of arrest when she was still in Moscow. "When all your friends are going to Paris,” she said, “going to Paris is not such a big thing...When all your friends are going to prison, going to prison is not such a big thing."

Those first 10 years were trying ones for Helsinki Watch. Unlike our colleagues in the other regional watch committees that eventually became Human Rights Watch, Helsinki Watch had no opportunity to engage with the Communist governments we criticized. They ignored our protests; we weren't sure they were even aware of them. Yet we persisted. Lyuda's unfailing confidence was a constant source of inspiration. And when the unthinkable actually happened, the dissolution of the Soviet Union in December 1991, Lyuda began taking steps to move back home and practice human rights activism in this new era.

In Moscow in September 1991, Lyuda, brimming with emotion, directed my gaze to the Russian flag flying above the Kremlin. The hammer and sickle were gone; Boris Yeltsin, then President of the Russian Republic, had banned the Communist Party in Russia. It was the beginning of the end. I was there to establish a Human Rights Watch office in Moscow, something that would have been unheard of just a few months before.

Lyuda found us the perfect office space. She introduced me to Sasha Petrov, who became our first Russian employee, a man of great dedication and ability who, working with Rachel Denber, the first director of our Moscow office, helped set up our Moscow operation. They interviewed victims of human rights violations in Russia, including in Chechnya, and throughout the former Soviet space, which at the time was riven with violent conflict.

In 1993, Lyuda moved back to Moscow permanently and set about creating a new Helsinki Group. When I visited Moscow in 2001, I witnessed its amazing evolution. Lyuda had created a new organization, staffed by young, bilingual professionals, modeled closely on Human Rights Watch and its Helsinki division. The group's reports, written in Russian, had covers with a similar format to those of Human Rights Watch.

"I am the chair," Lyuda told me proudly, the 'Bob Bernstein.' And wait till you meet our executive director, our 'Jeri Laber', he's terrific." During all those years that Lyuda worked with us, providing us with information about Soviet abuses and suggesting ways to combat them, I like to think she was also taking in everything that we did and, when the opportunity arose, she adapted it, in her own way and in constant evolution.

This year HRW turned 40. And the Moscow Helsinki Group exists to this day, despite the Kremlin, which is trying to put an end to most independent organizations. It has been protected, perhaps, by Lyuda's aura. May her spirit continue to fuel the group’s activities and to hold the government at bay.