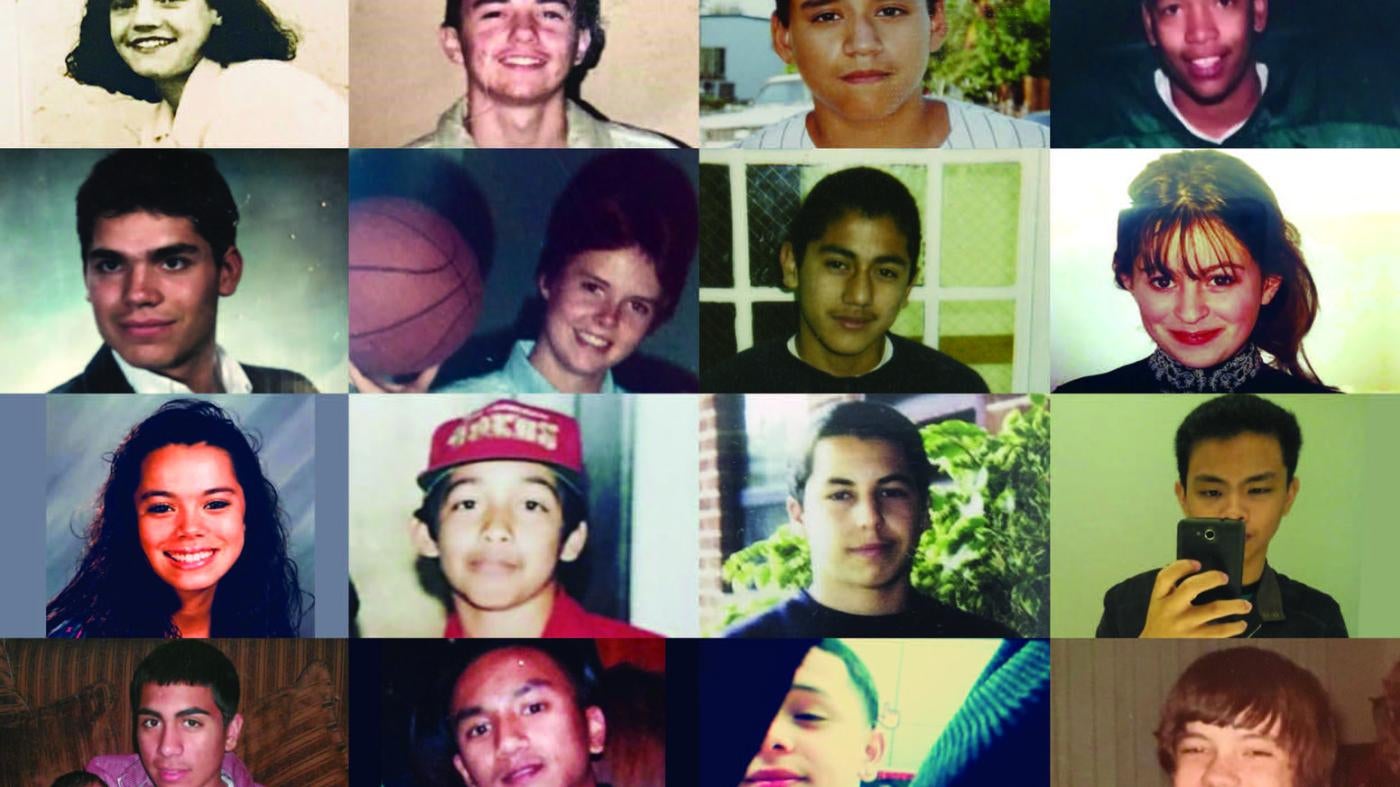

More than 1,500 children ages 15 and under have faced adult court sentences in California, including life in prison, since 2003.

Children under 16 can be given adult sentences that take no account of their youth and vulnerability. They are denied rehabilitation in the juvenile system and miss out on treatment, education, and counseling that have been proven to reduce re-offending by young people.

California is at a crossroads: the 1995 law that allows trying children under 16 as adults, passed as part of a “tough on crime” period. The years leading up to the law involved fear-mongering and false predictions of increased crime and the rise of “super-predator” youth.

But trying children in the adult system has proven to do more harm than good and increases rates of violence among youth moved into that system. A bill is pending that could correct this ill-conceived law and give 14- and 15-year-olds access to the youth justice services they need.

Miguel was involved in a street brawl and stabbed someone when he was 15. The person survived, and Miguel was charged with attempted murder. Just minutes after he was told the District Attorney wanted him tried as an adult, he found himself standing in court.

“I felt sick to my stomach,” he told Human Rights Watch over the phone. “My heart was racing. There was a lot of legality ... I had no idea what was going on.”

Realizing he might end up in prison with grown men, Miguel started working out, bulking up, preparing to defend himself. He believes that it was only because his mom cashed in her retirement fund and hired him a good lawyer that Miguel stayed in the juvenile system.

“I received counseling, and I unpacked my own pain, anger, and sadness. I was mentored. I began to understand how my actions impacted others,” he told us. “I was required to be in school and found I loved it.”

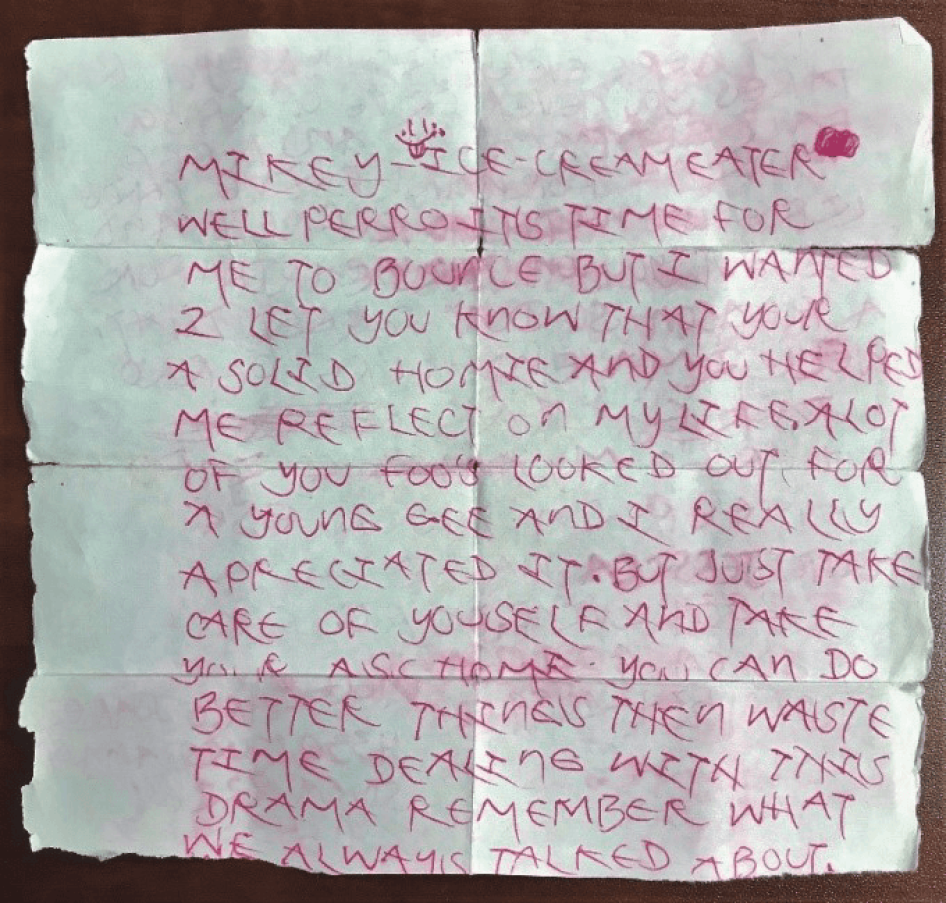

Miguel knows all too well his life could have gone down a different path. Three years into his sentence, “Jesse,” also 15 at the time of his crime, was moved into the cell next door. Unlike Miguel, Jesse was stuck on the path to being tried as an adult and was temporarily held in the juvenile facility.

With no hope of release, Jesse focused on protection and joined a prison gang, Miguel said. One day, Miguel returned to his cell and Jesse was gone, leaving behind a scrawled note to Miguel: “Don’t forget, God put you on this earth for a reason.” They never saw each other again. Jesse remains in prison, many years later.

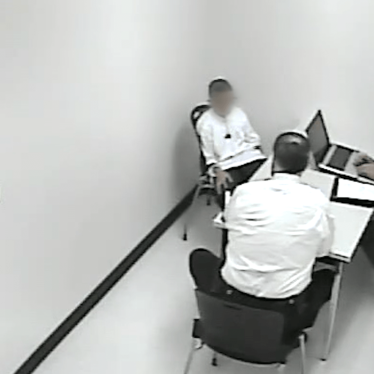

Even the transfer hearing – in which a judge decides if a child will be transferred into the adult justice system – can leave a lasting impact.

Daniel was 14 when he was sent to a transfer hearing that would decide whether he’d be tried as an adult and face life in prison for his involvement in a murder.

“They said I was ‘hardened criminal’ and that my behavior stemmed from being a ‘bad’ kid,” he told Human Rights Watch.

Daniel was fortunate and stayed in the juvenile justice system, but even as an adult, he remembers the impact of that hearing.

“I was 14, and I barely knew the definition of the words they used to describe me,” he said. “But the meaning was clear…I listened. I took it in. There was at least part of me that believed them.”

Recent US Supreme Court decisions acknowledge the developmental differences between children and adults. Teenagers, especially younger ones, have “diminished culpability” compared with adults, the court has written, and have a greater capacity for change and rehabilitation if given the proper support.

Decades of data show children who stay in the juvenile system are less likely to re-offend. Trying them as adults does nothing to reduce future crime.

In the youth justice system, young people are required to receive the same education as all children in California, and are required to participate in individualized services to address behavioral, health, disabilities, trauma, and other needs.

“I know all young people have the potential to change,” said Daniel who will graduate from the University of California at Davis this year. “They just need what I got. The juvenile system held me accountable for my actions.”

“I learned – really learned – what I did wrong and why. And, at the same time the juvenile system gave me opportunities that were integral to growth.”

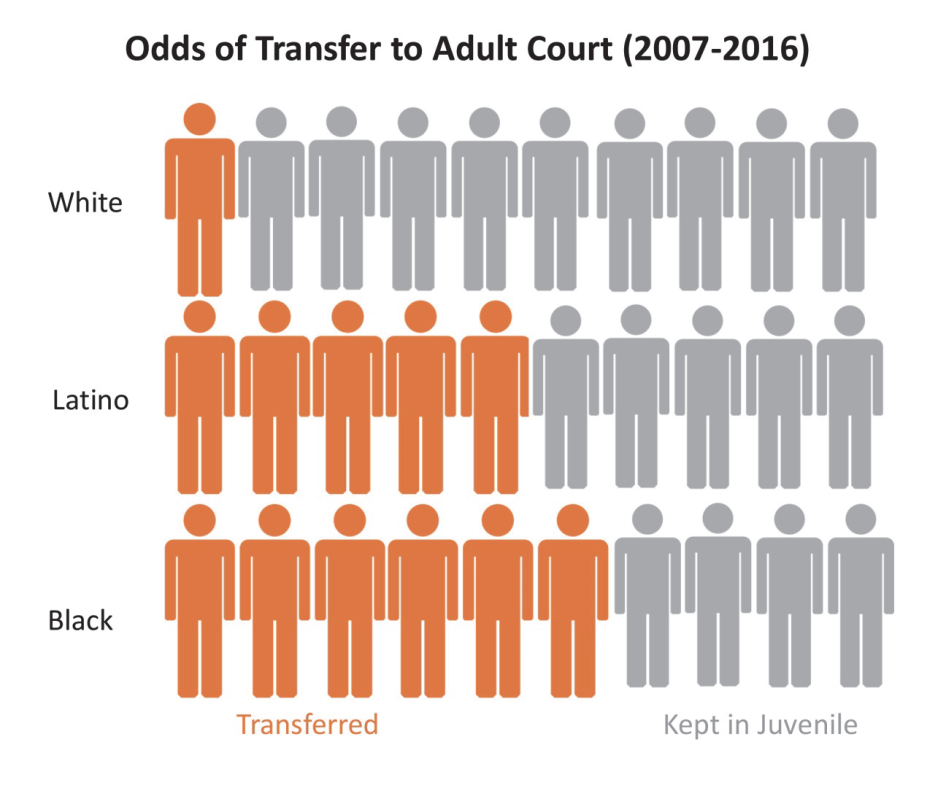

The current law’s harsh impact falls disproportionately on children of color, All youth subject to transfer hearings come into the courtroom with the same types of offenses, but, children of color see very different results. Black kids are 11 times as likely and Latinx kids nearly five times as likely to be sent to adult court as white kids.

If California approves law SB 1391, it will both protect public safety and promote the potential of young people like Daniel and Miguel. Everyone will at least have a chance at a future.

After leaving juvenile prison, Miguel earned three associate degrees with honors from community college, while working at least two jobs. He graduated with a BA from the University of California at Riverside in June 2018 and volunteers with at-risk youth. He interned with a member of the California state assembly and is on the national board of the Coalition for Juvenile Justice. This summer he is working in a policy fellowship and plans to attend law school.

“When I was 15, no one would have guessed I’d be where I am now, but I was lucky, and I got what I needed to become who I am today,” he said. “But Jesse was no different from me. If he had had that chance, he would have been like me.”