What does parallel construction look like?

We identified a case in Arizona where government officials illegally tracked a suspect’s rental car with a GPS device they’d secretly installed without a warrant. Then the federal official contacted the police near Flagstaff, Arizona, and told them to find a reason to pull over and search the car. So the local police pulled the person over, using the temporary paper license plate in the window as an excuse. They then used a drug-detecting dog to sniff the car and found drugs.

In the US we have a concept that’s called “the fruit of the poisonous tree.” That means prosecutors are not supposed to be allowed to enter anything stemming from an illegal search into evidence in court. If we let the government use something illegally gathered at trial, there’s little incentive for law enforcement to obey the law.

In the Arizona case, using the GPS device without a warrant violated Arizona law. In court the government pretended the case started with the minor traffic infringement, so the defendant went to prison without knowing that his rights were violated. The truth was revealed during a later federal trial, not the state trial that landed him behind bars.

But he had drugs on him. He was guilty. Why shouldn’t he be in prison?

Let’s look at the big picture. Everyone has the right to a fair trial. If the government does something illegal, it doesn’t get to benefit from it.

One of the problems here is that you can have the government deciding for itself what’s legal, and potentially hiding things it thinks are acceptable but that may not actually be constitutional. Sometimes, too, the government may be concealing activities it knows or should know are unlawful, as in the Arizona case.

If you’re a defendant, you need to be able to question what the government did. And if you’re a judge, you need to be able to play your role, which is to determine whether evidence was found legally. If the true circumstances of how the government got the evidence are hidden, neither of those things can happen. When it uses parallel construction, the government usurps the role of the judge—and leaves both judges and defendants in the dark.

What if an innocent person goes to prison? Or what if the government were engaging in illegal surveillance that affected a specific community? The ramifications go far beyond the particular case. We might never know about a very problematic activity because the government was covering it up.

Getting back to your question, people are innocent until proven guilty. That makes it especially important for the government to respect the rules in all cases, even where law enforcement is convinced someone committed a crime.

What new information on this practice does your report reveal?

We interviewed a former federal prosecutor who was part of the DEA’s Special Operations Division and who suggested that it regularly distributes tips – maybe even daily. But I don’t believe we’re seeing the disclosure of the sources of those tips when the cases go to court.

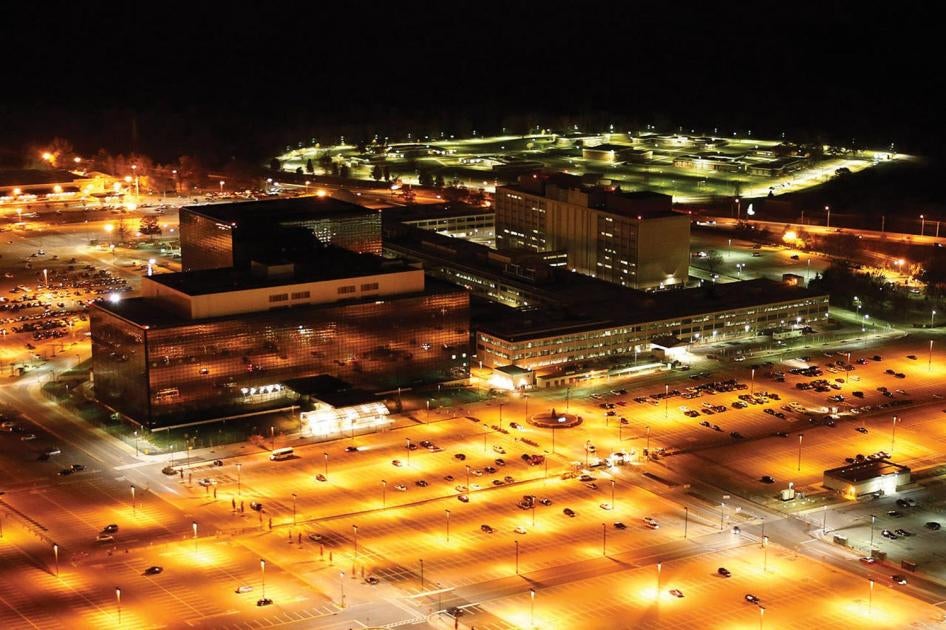

We also have many examples of defense attorneys who tried – and failed – to pinpoint parallel construction. We have prosecutors who refused to check with the US National Security Agency or other intelligence agencies to see if, say, they passed on tips from some huge surveillance program.

How did you find the defense attorneys that ran into these problems if they themselves couldn’t identify them?

Researching anything that might touch on a classified subject is very difficult. We did a ton of outreach to defense attorneys, saying, did you ever have a case where something didn’t feel quite right? And slowly, painstakingly for more than a year, we found attorneys who had suspected parallel construction.

We also learned that traffic stops originating from federal tips are called “wall stops” and “whisper stops.” Once I knew those terms, I could do a search of a legal database or on Google. We ultimately found records of 95 relevant court cases.

We reached out to current and former government officials we knew, and found others by looking at government records.

We also combed through several hundred pages of information regarding DEA training that were released to a journalist via the Freedom of Information Act after Reuters first reported on parallel construction in 2013.

The nature of a cover-up is that it’s very hard to identify. If I wanted to hide something and ripped up my floor, hid the item, and laid a new floor, it’s hard for someone to come in and say something’s wrong.

Is the DEA the agency most involved in parallel construction?

We have the most evidence for the DEA, but we found cases where other agencies admitted to requesting “wall stops.”

One of the people we interviewed was Derrick Maltz, who for a long time was the special agent in charge of the DEA’s Special Operation Division. A piece of the puzzle is understanding this unit, where law enforcement information is centralized and where our sources suggest many tips leading to prosecutions originate. Arthur Rizer, a former prosecutor working in the Special Operations Division, suggested to us that SOD tips were used for prosecutions daily when he was there.

We also talked to another former prosecutor who said they had been part of the division’s “Dark Side,” but then wouldn’t elaborate much on what this was except to say that it “does stuff that doesn’t come to the public’s attention.”

The Dark Side? Like Star Wars?

We don’t know much about the “Dark Side” and think the public deserves to know more.

One source said the nickname is tongue in cheek, and that people got Darth Vader keychains when they left. Even if it’s in jest, it does seem to indicate that whatever the “Dark Side” is, it may be walking up to the legal line. And we don’t all agree where that line is.

We’re not saying law enforcement or prosecutors or intelligence agencies lack integrity. They may think everything they’re doing is legal. We’re saying we disagree. We think the cover-up method violates rights, that people aren’t getting their day in court, and that defendants are subject to unfair trials. Also, it isn’t up to the government to decide whether its activities are legal or not. In the US, that’s a decision for the judge.

Are there any other cases that stick out?

There was a case in New Mexico, where a bus pulled into the bus station for a layover. People got off the bus, leaving their carry-on bags behind. Security video caught a DEA [Drug Enforcement Agency] agent boarding the bus while only the driver was on it, and staying there for several minutes. The agent is also recorded on surveillance video feeling up the checked bags outside the bus in a way that many attorneys would likely say was unconstitutional – the Supreme Court has said you can only manipulate somebody’s bag if you have a warrant.

The passengers re-board the bus, and – as the defense tells it -- the agent is standing by one passenger’s seat, waiting for him. The agent asks if he can search the passenger’s carry-on bag. Eventually, the passenger gives consent. The DEA agent opens the bag and finds meth.

The defense alleged that, given the way the DEA agent targeted this one person, the agent had illegally and secretly searched the carry-on luggage. But the judge, after considering for a long while, overruled the motion because the security cameras couldn’t see inside the bus and the defense didn’t have enough solid proof. That case looked an awful lot like parallel construction, even though we can’t prove it.

Was there any information you couldn’t find?

We’re still lacking information from police officers on the ground. For example, there have to be officers who are carrying out the kind of pretextual traffic stop that happened in the Arizona case and who think this practice might be a problem. This report should be a springboard for local investigations.

If you worry that you may have been a part of this, get in touch—I want to hear from you. This is not the end of my research, it’s the beginning.

Any last point you’d like to make?

This issue is not just about people defending themselves on criminal charges. If the government can conceal potentially illegal activities, it could affect us all. For example, there could be surveillance programs that focus on people of color, religious minorities, or other communities in a way that’s discriminatory. The only way to avoid this is to have the government disclose what it does. Until parallel construction is banned, we’re all at risk. If agents can violate the Constitution without any consequence, do your constitutional rights still have any meaning?

This interview has been edited and condensed.