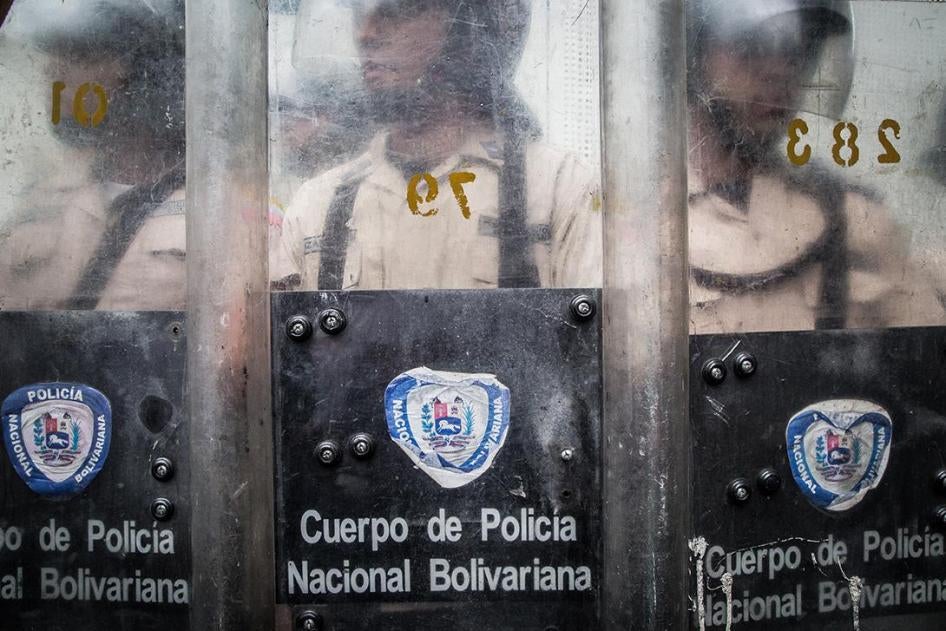

Brutality, Torture, and Political Persecution in Venezuela

With Venezuela in the middle of a massive humanitarian crisis, why is it important to focus on detention?

These issues are inseparable. The humanitarian crisis has fueled widespread discontent with the government. Last April, tens of thousands of people took to the streets to protest the government-controlled Supreme Court’s attempted power-grab from the legislature. But these protests grew and extended throughout the country in large part because of the generalized discontent many felt, not only with the government’s authoritarian practices but also with its handling of the humanitarian crisis. The government’s response to the protests was widespread brutality. The scope and the severity this year has reached levels we hadn’t seen—with security forces and armed pro-government gangs called “colectivos” repressing peaceful protesters, and detainees subject to terrible abuse, including in some cases torture.

How many cases did you document?

We interviewed more than 120 people, the majority abuse victims or their relatives. We also collected information that corroborated that testimony, and documented 88 cases of alleged abuse involving at least 314 victims. We concluded that many of the abuses by the security forces were systematic. We also identified high level officials—including the president, the defense minister and the interior and justice minister—who failed to prevent or prosecute these abuses under their watch.

What types of torture did you uncover and who was behind it?

We learned that security forces acted directly or allowed colectivos to repress protesters, leading to dozens of killings and hundreds of injuries. We’ve seen how they shot at protesters, and used water cannons, pellet guns, and teargas canisters in a way that seemed intended not to disperse protesters but to inflict pain. In some cases, colectivos illegally detained people and then turned them over to government security forces.

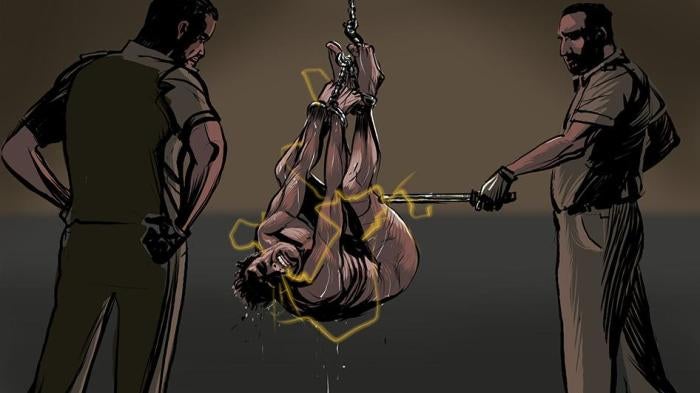

We saw cases where security forces beat protesters and tortured them using asphyxiation, electric shocks, sexual abuse and other brutal techniques.

Some of the people detained have been charged with crimes such as rebellion and treason in front of military tribunals. More than 750 people were prosecuted by military courts this year. It is a practice that we used to see in the dictatorships of the 1970’s in the southern hemisphere.

What cases stand out for you?

One man who published information critical of the government was taken from his home by intelligence agents and detained for more than 50 days. He never saw a judge, his family, or an attorney. They stripped his clothes, cuffed his wrists and ankles, and suspended him from the ceiling where they shot water at him and gave him electric shocks to force him to say he had links to the political opposition.

Other heartbreaking cases are those where young people went to protest because they wanted a better country, and they ended up killed by the security forces who fired at close range. We know security forces have fired tear gas directly at protesters, or fired glass and other dangerous material from weapons meant to discharge non-lethal riot munitions.

One young man said that he was shot at and detained by the Bolivarian National Guard while on his way to play basketball. In detention, they beat him and threatened to kill him. They made him squat walk, they beat him with batons, they cut his hair and forced him to do some military training. They made him bend over until his head touched the ground, and then balance on his head and feet in a sort of pike position without using his hands. They also put him in a tiny cell nicknamed “tigrito,” or tiger cell, possibly because they are very small -- some say are the size of tiger carriers – or because of their foul smell due to overcrowding.

What’s the impact of the crisis on Venezuela’s neighbors?

Venezuelan emigration has increased sharply. Tens of thousands are fleeing to neighboring Colombia. In Brazil, between January and February, 7,600 Venezuelans asked for refuge, compared with 4 in all of 2010. In Argentina, temporary visas for Venezuelans have doubled every year since 2014. In May, they reached a total of 35,600 issued visas. It’s all over the region.

These Venezuelans generally feel that they have been forced to leave Venezuela, be it by the political climate and persecution or the humanitarian crisis.

The irony is, Venezuela is a country that traditionally received immigrants, including people who fled Latin American dictators in other countries.

Your family sought refuge in Venezuela in the past. Does this give you a personal connection?

It does. I was born in Venezuela because my parents were exiled from the Argentine dictatorship in the 1970’s. Today I live in Buenos Aires – my family returned to Argentina when democracy was restored there, but I still have a personal connection to Venezuela.

What’s it like working in a country that has barred you from entering?

The last time Human Rights Watch tried to do public advocacy in Venezuela, in 2008, our representatives were arrested and expelled from the country. So now we keep a low profile and avoid contact with authorities. Many of the victims’ or activists’ phones are tapped, so we chat through encrypted communications. We meet in secure locations. When our researchers are in the field, we are in close contact to always know where they are and what they’re doing.

We usually contact victims through someone they trust, such as their lawyer or a non-governmental organization. This is a joint report with a local Venezuelan group called the Penal Forum, a network of lawyers who do pro bono work, and they helped set up many of the meetings.

You’ve worked undercover in Venezuela for years, but during this crisis decided to go public with your identity. Why?

It was a difficult decision. A lot of people knew I was doing this work, even though I never was on the Human Rights Watch website and my name never appeared on anything we did. But after years of going there frequently and being in touch with people, in the same way I had all these people in my phone contacts, they had me in theirs. And that meant we were increasing the risks for myself and for the people I worked with.

This coincided with the tailspin of the crisis in Venezuela. We decided it was more important and effective for me to speak out publicly about what was happening there, with the legitimacy of having been in the country for eight years.

I still interview people who fled the country, carry out interviews from abroad, and supervise on-the-ground research.

What did your friends there say?

It was a difficult personal decision because it meant that I wasn’t going to be able to go back. I no longer have family in Venezuela, but I have friends there. In a way, this is my second exile. I was born into exile in Venezuela, and now I’m being forced to stay away from the country that sheltered my family. And that is very difficult.

How has it been, being public?

We weren’t really sure what would happen once I became a spokesperson. My sense is that we were right. People listen to you differently when you talk about what you saw with your own eyes -- both journalists and government officials. And that’s an important part of our job, to transmit that message in the most powerful way.

What do you want to see happen now?

Some people may think that Venezuelan security forces are behaving better because we don’t see many headlines about people getting killed on the streets. The truth is there is only less repression because there are fewer demonstrations. The government hasn’t given any indication of easing up on repression. We want people to know what we know, and to help generate international pressure on the Venezuelan government to end its repressive practices and restore democratic rule. And we also want to use our findings to make sure that those responsible for the abuses are eventually brought to justice.

This interview has been edited and condensed.