Honourable Commissioner Asuagbor

African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights

21 Bijilo Annex Layout, Kombo North District

Banjul, The Gambia

Re: Human Rights Situation in Rwanda

Dear Commissioner Asuagbor,

We are writing to you in your capacity as the country rapporteur for Rwanda.

Human Rights Watch has worked on Rwanda for over 20 years. For most of the time between 1995 and 2013, we had a researcher based in the country. This has become more difficult since 2013, when we last were able to secure work visas. However, we are still able to access the country and our work continues.

We remain deeply concerned by human rights violations that continue to occur in the country, attempts by government agencies and actors to cover up these violations and the limited space in the country for free expression.

The Rwandan government continues to limit the ability of civil society groups, media, and international human rights organizations to function freely and independently and criticize its policies or practices. We have documented how military and police arbitrarily arrested and detained people in unofficial detention centers, torturing and ill-treating some of them. Summary executions from April 2016 to March 2017, and subsequent threats to family members of victims who spoke with us, have terrified people in the Western Province.

We outline these concerns in more detail below. We would be happy to follow up with supporting information and, if requested, with briefings from our staff who work on Rwanda.

In your capacity as country rapporteur for Rwanda, we hope that you will work with the government of Rwanda and reinforce key human rights principles including: respect for rule of law, freedom from arbitrary or unlawful detention, freedom from torture, and freedom of association and of opinion and expression, in particular the right to hold political views contrary to the government. We also ask you to urge the government to take seriously and investigate all allegations of extrajudicial killings and torture and ensure accountability for serious crimes.

Wendy Issack, researcher at Human Rights Watch, is attending the 61st Ordinary Session in Banjul and would greatly appreciate the opportunity to meet with you at your convenience to further discuss the human rights situation in Rwanda. She can be reached at [...].

We look forward to actively participating in the forthcoming 61st Ordinary Session.

Respectfully,

Ida Sawyer

Director, Central Africa

Annex: Summary of Recent Human Rights Violations Documented by Human Rights Watch

Political Pluralism and Freedom of Expression

In a referendum in December 2015, Rwandan citizens overwhelmingly voted in favor of constitutional amendments that allowed President Paul Kagame to run for a third term in 2017 and two additional five-year terms thereafter. Very few voices inside the country publicly opposed the move.

Presidential elections, held on August 4, 2017, took place in a context of very limited free speech or open political space. Between the referendum and the election, which Kagame won with a reported 98.79 percent of the vote, we noted many violations of the rights to freedom of expression, association, and assembly across the country.

We spoke with local activists and private citizens who spoke of intimidation and irregularities in both the lead-up to the election and during the voting including forced donations to the ruling party, the inability to vote in private and falsified ballots.

One would-be independent candidate, Diana Rwigara, was barred from running and is currently in detention. The harassment of Rwigara began in May, when – 72 hours after she announced her intention to run in the presidential election – nude photos of her were published on social media in an apparent attempt to humiliate and intimidate her. The National Electoral Commission later rejected her candidacy, claiming that many of the required signatures supporting her candidacy were invalid. Rwigara rejected the accusations and said she had fulfilled the eligibility requirements.

On August 30, following rumors that Rwigara may have been arrested or forcibly disappeared, the police announced that she was not in detention but that she was under investigation. After several weeks of intimidation, questioning, and restrictions on their movements, Rwigara, her sister and her mother were arrested on September 23. They are being held in police custody in the capital, Kigali. Her sister was released on bail on October 23. Rwigara is charged with incitement and forgery. We have real concerns that these charges are politically motivated, and we question whether Rwigara will be able to receive a fair trial.

Rwigara’s arrest comes amid growing pressure on other political opponents. On September 6, seven members of the Forces Démocratiques Unifiées (FDU)-Inkingi, a banned opposition party, were arrested, including four of the party’s leaders. They are charged with forming an irregular armed group and offenses against the president. Another party member was forcibly disappeared on September 6 and held incommunicado for 17 days, before a family member could visit him at a police station.

The BBC Kinyarwanda service was banned by the government in May 2015 after a committee concluded that a BBC television documentary, “Rwanda’s Untold Story,” had, among other things, abused press freedom and violated Rwandan law relating to genocide denial and revisionism, inciting hatred and divisionism.

Since the BBC was banned, the Voice of America remains the only independent radio station airing programs in the national language across the country. The Voice of America’s Kinyarwanda service has reported on sensitive topics such as Human Rights Watch reports in 2017 and on the trial of Diane Rwigara and her family.

John Ndabarasa, a journalist from Sana Radio, a local radio station, went missing on August 8, 2016, only to resurface in Kigali, on March 6, 2017. Ndabarasa is a relative of Joel Mutabazi, a former presidential bodyguard sentenced to life imprisonment in 2014 for security-related offenses. In a story that raised suspicions for many, Ndabarasa told journalists that he had fled the country and later decided voluntarily to come back. His disappearance and the scant information that has emerged since he reappeared sent a chilling message to other local journalists.

Extrajudicial Executions of Petty Offenders

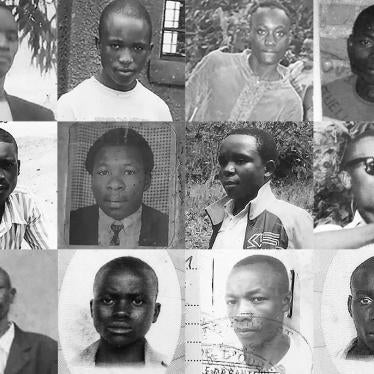

State security forces in Rwanda summarily killed at least 37 suspected petty offenders and forcibly disappeared four others in Rwanda’s Western Province between April 2016 and March 2017. Most victims were accused of stealing items such as bananas, a cow, or a motorcycle. Others were suspected of smuggling marijuana, illegally crossing the border from the Democratic Republic of Congo, or of using illegal fishing nets.

Authorities used the extrajudicial executions to serve as a warning. In most of the cases, local military and civilian authorities told residents, often during public meetings, that the suspected petty offender had been killed and that all other thieves and criminals in the region would be arrested and executed.

We reported on these killings in July and government officials quickly called the report “fake news.”

Numerous family members of victims told Human Rights Watch that local authorities interrogated, threatened, or even detained them in the aftermath of our report.

On October 13, the government of Rwanda’s National Commission for Human Rights issued a report designed to discredit the allegations of extra judicial killings and enforced disappearances, and attack Human Rights Watch. The commission’s report, compiled following intimidation and threats against witnesses, and its corresponding press conference were largely fabricated, misrepresented Human Rights Watch’s work and led to a string of disparaging and unfounded comments against our staff from government officials and parliamentarians.

Unlawful Detention in “Transit Centers”

We have conducted research on unlawful detention since 2010, and we have released several reports based on our findings.

For at least the last twelve years, Rwandan authorities rounded up poor people and arbitrarily detained them in so-called “transit centers” (also called “rehabilitation centers”) across the country. The conditions in these centers are often inhuman and reflect a government perception of certain groups of people as offenders or sources of nuisance, rather than victims or vulnerable people.

Homeless people, street vendors, street children, sex workers and other poor people were taken off the streets and detained in these centers for prolonged periods. Detainees had inadequate food, water, and health care; suffer frequent beatings; and rarely leave their filthy, overcrowded rooms. Since 2014, we interviewed over 100 former detainees at these centers. None of them were formally charged with any criminal offense nor saw a prosecutor, judge, or lawyer before or during their detention. We remain concerned about this lack of due process and consider these detentions arbitrary and unlawful.

While these centers are officially meant to “rehabilitate” people through professional training or education, most of the people we interviewed did not receive such training and were treated as prisoners.

Conditions at the different “transit centers” are similar. Police or other groups responsible for security rounded up the detainees and transported them to the centers. Most detainees were not allowed to leave their room, except to go to the toilet only twice a day. In most cases, food was no more than one cup of corn a day, and several former detainees complained about the lack of drinking water or the opportunity to wash.

Beatings by either police or other detainees were commonplace.

Unlawful Detention and Torture in Military Camps

Scores of people suspected of collaborating with “enemies” of the Rwandan government were detained unlawfully and tortured in military detention centers by Rwandan army soldiers and intelligence officers from 2010 to 2017. Some of these people were held in unknown locations, including incommunicado, for prolonged periods and in inhuman conditions.

Torture and illegal detention are designed to extract information from real or suspected members or sympathizers of the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR)—an armed group based in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo—and, to a lesser extent, the Rwanda National Congress (RNC), an opposition group in exile, and the Forces Démocratiques Unifiées (FDU)-Inkingi.

Most of the detainees were held near the capital, Kigali, or in northwestern Rwanda.

Severe beatings, electric shocks, asphyxiation and mock executions were used to force suspects to confess, or to incriminate others. Former detainees were held for up to nine months in extremely harsh and inhuman conditions, with insufficient food and water to meet their basic needs.

In many cases, after several months of illegal detention—and often only after detainees had signed a statement under torture—the Rwandan authorities transferred them to official detention centers, including civilian prisons, and they were then charged and put on trial. The period of their detention in military centers was erased from the public record.

Despite being told not to reveal the abuses they faced in detention, many of the defendants told judges they had been illegally detained or tortured in military detention centers. We are not aware of any judges ordering an investigation into the allegations or dismissing evidence obtained under torture.

The violations documented in our most recent report (released in October 2017) are in clear violation of Rwandan and international law, including several treaties such as the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights and the Convention against Torture, which prohibit enforced disappearances, arbitrary and unlawful arrest and detention, and the use of torture and other ill-treatment.

In October, the Subcommittee on the Prevention of Torture, a monitoring body of the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture, (ratified by Rwanda in 2015), conducted a state visit to Rwanda. They had to suspend their visit and leave sooner than planned, however, citing obstruction from the Rwandan government and fear of reprisals against interviewees. This was only the third time in ten years that the Subcommittee has suspended a visit.