The Australian government will let people “have their say” on same-sex marriage. The Australian High Court ruled Thursday that the government’s postal plebiscite can proceed, so next week ballots will arrive by mail, asking voters: “Should the law be changed to allow same-sex couples to marry?” This non-binding vote has been criticized for being a “glorified opinion poll” and a symptom of the country’s parochial and paralyzing politics. Since the elected parliament could simply pass a marriage equality bill, the plebiscite seems little more than a costly and unwieldy bit of political pageantry.

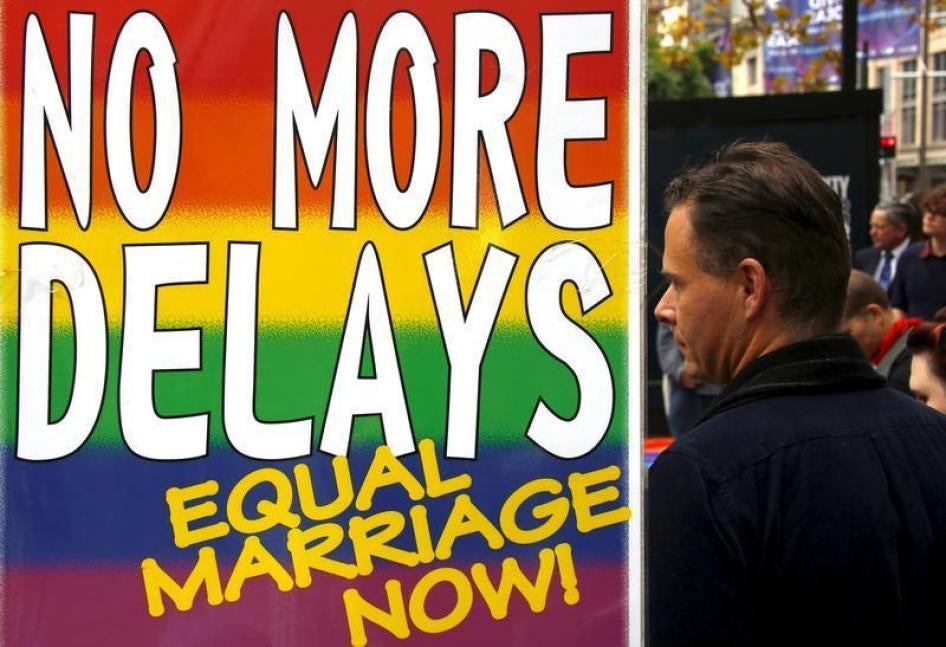

But the plebiscite carries a less obvious cost in human dignity. Other countries around the world that have voted on marriage equality in recent years—including those endorsing it—show how this type of spectacle can leave deep wounds against an already marginalized community.

Australia is no longer one of 73 countries that forbid same-sex intimacy. Neither does Australia have laws—as other countries do—that curtail the right to free expression or inhibit freedom of association for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people. Sydney is host to the world-renowned Mardi Gras LGBT pride festival. But Australia does not allow same-sex marriage, lagging behind the 22 countries, including New Zealand and the United States, that do.

Employing direct democracy to cast ballots on individual rights is dangerous. Ireland upheld LGBT rights when the majority Catholic country voted overwhelmingly in favor of marriage equality in 2015. Bermuda’s June 2016 referendum rejected same-sex marriage. But regardless of the outcome, such votes are like letting the electorate decide whether domestic violence should be criminalized. Or whether an unpopular ethnic minority should enjoy freedom from discrimination. Or whether members of a religious group can openly practice their faith.

While the votes in Ireland and Bermuda had different outcomes, the process of the referendum cast a similarly disturbing shadow. In both countries, the referendums forced LGBT people to open their lives and identities to public debate, scrutiny, evaluation, and sometimes abuse.

In Australia, it means gay and lesbian brothers, sisters, fathers, mothers, and neighbors have to ask their kin, their community, and total strangers, “Are you OK with me getting married?” What that really means is:

“Do you see me as your equal? Is my love as true as yours? Is my family as valuable?”

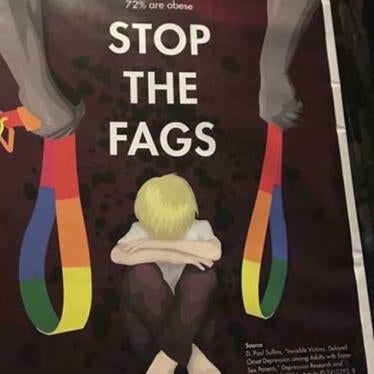

And while polls suggest that many Australians are ready for same-sex marriage, holding a plebiscite gives a tacit legitimacy to objections that include equating homosexuality with bestiality to scare tactics claiming that marriage equality will limit religious freedom.

And that vitriol comes in addition to the sustained and intense scrutiny these vulnerable communities will have to endure.

LGBT Australians shouldn’t have to run that gauntlet for their rights to be respected.

While the plebiscite does not bind the parliament, it is expected that the Turnbull government will not endorse a marriage equality law unless there is a majority yes vote. The government should not be able to let itself off the hook on a matter of basic rights.

It is perpetuating a dangerous practice by asking Australians—most of whom are not directly affected by the inequality in the Marriage Act 1961—whether they are ready for a minority to enjoy equal rights. The government should demonstrate the same decisiveness as the New Zealand parliament, which took the responsibility upon itself.

Making people beg for their rights is not just. While Australia may be on the brink of joining the right side of history on marriage equality, there are ways to get there that fully uphold human dignity.